Stephen Kemble

Stephen Kemble | |

|---|---|

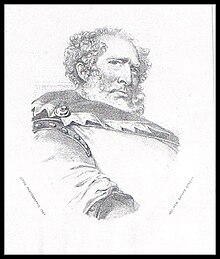

Stephen Kemble as Falstaff | |

| Born | 21 April 1758 |

| Died | 5 June 1822 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Chapel of the Nine Altars in the Durham Cathedral. England |

| Occupation(s) | Manager, Actor, Writer |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Satchell |

| Parent(s) | Roger Kemble and Sarah Ward |

George Stephen Kemble (21 April 1758 – 5 June 1822) was a successful theatre manager, British actor, writer, and a member of the famous Kemble family.

He was born in Kington, Herefordshire, the second son of Roger Kemble, brother of Charles Kemble, John Philip Kemble and Sarah Siddons. He married prominent actress Elizabeth Satchell (1783). His niece was the actress and abolitionist Fanny Kemble. His daughter Francis Kemble married Richard Arkwright junior's son Captain Robert Arkwright. Kemble's son Henry was also an actor.

Manager

Similar to his father, Stephen Kemble became a very successful theatre manager of the Eighteenth-Century English Stage. He managed the original Theatre Royal, Newcastle for fifteen years (1791–1806). He brought members of his famous acting family and many other actors out of London to Newcastle. Stephen's sister, Sarah Siddons was the first London actor of repute to break through the prejudice which regarded summer " strolling," or starring in the provincial theatres, as a degradation.[1] Stephen Kemble guided the Theatre through many celebrated seasons. The Newcastle audience quickly came to regard itself, that is, as "in a position of great theatrical privilege.".[2] The original Theatre Royal was opened on 21 January 1788 and was located on Mosley Street, next to Drury Lane. While in Newcastle upon Tyne Kemble lived in a large house opposite the White Cross in Newgate Street.

-

Royal Theatre, Newcastle

-

Kemble Theatre Ticket

-

Stephen Kemble

-

Kemble by John Raphael Smith, National Portrait Gallery

Stephen Kemble quickly branched out and began to manage other theatres: Theatre Royal, Edinburgh (1794–1800)); Theatre Royal, Glasgow (eventually replaced by Tivoli Theatre (Aberdeen)) (1795);[3] Chester; Lancaster; Sheffield (1792); Berwick-upon-Tweed (1794),;[4] theatres in Northumberland; Alnwick (where he builds a theatre)(1796) and rural areas on the theatre circuit. From Newcastle, Kemble ran the Durham circuit (1799), which included North Shields, Sunderland, South Shields, Stockton and Scarborough (opening for the Stockton Racecourse). He also managed theatres at Northallerton and Morpeth. In Broadway, he performed in the Assembly Room of the Lygon Arms (formerly known as the White Hart Inn).[5] He also managed Whitehaven and Paislie (1814),[6] Northampton Theatre,[7] the theatre at Birmingham [8] and Theatre Royal, Dumfries,[9] Portsmouth. For a short time in 1792, actor Charles Lee Lewes assisted Stephen Kemble in the management of the Dundee Repertory Theatre

He supported the careers of many leading actors of the time such as Master Betty, his wife Elizabeth Satchell, his sister Elizabeth Whitlock, George Frederick Cooke, Harriet Pye Esten, John Edwin, Joseph Munden, Grist, Elizabeth Inchbald, Pauline Hall, Wilson, Charles Incledon, Egan. His nephew Henry Siddons (Sarah Siddons' son) made his first appearance on stage in Sheffield (October 1792), his younger brother Charles Kemble, Thomas Apthorpe Cooper, John Liston, John Emery, Daniel Egerton, William Macready.

Stephen presented London stars such as Edmund Kean, Alexander and Elizabeth Pope (née Elizabeth Younge), Mrs. Dorothea Jordan, his brother John Philip Kemble, Wright Bowden, his sister Sarah Siddons, Elizabeth Billington, Michael Kelly (tenor), Anna Maria Crouch, and Charles Lee Lewes.

Actor

He was also famous for playing Falstaff. Contemporary critics acclaimed that in this role Kemble achieved the "optimum balance between comedy and gravity."[10] After his performance in London at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1802, the Morning Chronicle wrote that "It is to be regretted that his associations in the country prevent him from accepting a permanent engagement in London."[11] Kemble would return to play Falstaff in London at Covent Garden (1806) and the Drury Lane (1816), for which he received great acclaim. After Kemble's death, The Edinburgh literary journal wrote, "[Stephen] Kemble was perhaps the best Sir John Falstaff which the British stage ever saw."[12]

Kemble also played the title roles in Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, Shylock in The Merchant of Venice and many other roles.

Writer for The London Magazine John Taylor wrote, "Mr. Stephen Kemble was an actor of considerable merit."[13] Taylor writes about Kemble's commitment to address injustice through theatre: "All characters of an open, blunt nature, and requiring a vehement expression of justice and integrity, particularly those exemplifying an honest indignation against vice, he delivered in so forcible a manner, as to show. obviously that he was developing his own feelings and character. This manner was very successfully displayed in his representation of the Governor, Sir Christopher Curry, in the opera of Inkle and Yarico." [14]

Taylor writes of Kemble's reputation in the provincial theatre circuit: "Stephen Kemble, who was an accurate observer of human life, and an able delineater of character and manners, was so intelligent and humorous a companion, that he was received with respect into the best company in the several provincial towns, which he occasionally visited in the exercise of his profession." [15]

Writer

He also published a dramatic play The Northern Inn (1791). The play was also known as The northern lass, or, Days of good Queen Bess, The good times of Queen Bess. The play was first produced 16 August 1791, as The northern inn, or, The good times of Queen Bess, at the Haymarket Theatre (i.e. Little Theatre or Theatre Royal, Haymarket).

Kemble also published a collection of his writings Odes, Lyrical Ballads and Poems on various occasions (1809). About Kemble's poetry, John Wilson (Scottish writer) stated, "Stephen Kemble was a man of excellent talents, and taste too; and we have a volume of his poems... in which there is considerable powers of language, and no deficiency either of feeling or of fancy. He had humour if not wit, and was a pleasant companion and worthy man."[16] Of particular interest is Kemble's writing is his reflections on contemporaneous events such as the Battle of Trafalgar, the death of Lord Nelson, the death of Robert Burns, his conversion to the abolitionist movement and support of the Slave Trade Act 1807,[17] the death of his brother-in-law William Siddons.

Stephen published a play with his son Henry Kemble (1789–1836) [18] entitled Flodden Field (1819) based on the Battle of Flodden (1513). The text is based on Sir Walter Scott's Marmion: a tale of Flodden field. In six cantos. The play was first performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on Thursday evening, 31 December 1818. The European Magazine, and London Review reported that at its debut "the whole [play] went off without opposition, and its repetition, was received with applause."[19]

An essay of his entitled "In the Character of Touchstone, Riding on an Ass" was published by William Oxberry in his book The Actor's Budget (1820).

Retirement

Kemble moved from Newcastle to Durham, and lived in retirement after 1806. In later life, Kemble took on less responsibilities in management and made only occasional appearances on the stage.

He was a close friend of another famous Durham resident, the 3 ft 3 inch tall Polish dwarf, Józef Boruwłaski. When these two friends - one little and one large - strolled along the wooded paths of the city, they were reported to be an interesting sight for the people of Durham.

Kemble's last performance at Durham was in May 1822, a fortnight before his death at the age of 64. He was fondly remembered by the natives of Durham, and was honoured with a burial in the Chapel of the Nine Altars in the Durham Cathedral. He and his close friend Józef Boruwłaski were buried beside each other. The heyday of Durham theatre came to an end with Kemble's death.[20]

In 2013, lines from his ode to a Guinea were inscribed on the rim of a £2 coin issued to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the Guinea coin. "What is a Guinea? 'Tis a splendid thing"."[21]

References

Primary Texts

- K. E. Robinson (1972). "Stephen Kemble's Management of the Theatre Royal, Newcastle upon Tyne" in Richards, K. and Thomson, P. (eds). Essays on the Eighteeenth-Century English Stage

- A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Volume 8, Hough to Keyse: Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers, and Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660–1800 ... Dictionary of Actors & Actresses, 1660–1800)by Philip H. Highfill, Kalman A. Burnim, Edward A. Langhans Published on 2 August 1982, Southern Illinois University

Notes

- ^ REMINISCENCES OF SHEFFIELD by R.E.LEADER - CHAPTER VII. THE THEATRES AND Muslc.

- ^ K. E. Robinson (1972). "Stephen Kemble's Management of the Theatre Royal, Newcastle upon Tyne" in Richards, K. and Thomson, P. (eds). Essays on the Eighteenth-Century English Stage p.142

- ^ Stephen Kemble published his "Epilogue on opening the Aberdeen Theatre" in his book Odes, Lyrical Ballads and Poems (1809).

- ^ Where he built the theatre in 1794 in a disused malt-house at the back of the King's Arms Inn. At the opening the freemasons attended in force, remaining patrons throughout the theatre's existence. The theatre was usually opened a week or two before the Lamberton Races in the first week of July and continued for three or four weeks.

- ^ The house in Westgate was during its long existence the only regular theatre in the town it used to announce itself on the bills simply as " Theatre, Wakefield," but other places have been occasionally used for dramatic entertainments, and some of them may be noted in passing. Before the theatre was opened there were two rooms, both apparently attached to inns, which were taken possession of from time to time by the strolling player ; the one situated in the Bull Yard, and the other in the George Yard. These we shall meet with hereafter. The Assembly Room at the old White Hart, a room said to have been about the size of the present Music Saloon and in which, by the way, Stephen Kemble once gave recitations was also during the early part of this century sometimes turned into a theatre. The Old Wakefield Theatre by William Senior Wakefield. Radcliffe Press. 1894 p. 6

- ^ Stephen Kemble published his "Address on opening the Theatre in Whitehaven" in his book Odes, Lyrical Ballads and Poems (1809).

- ^ Stephen Kemble published his "Address on opening the Northamton Theatre" in his book Odes, Lyrical Ballads and Poems (1809).

- ^ The Life of Edmund Keen, p. 85

- ^ Stephen Kemble published an address his wife gave at the theatre in 1973 entitled "Burns, the Scottish Bard" in his book Odes, Lyrical Ballads and Poems (1809).

- ^ (Robsinson, p.137

- ^ Morning Chronicle 8 October 1802.

- ^ The Edinburgh literary journal; or, Weekly register of criticism ..., Volume 3 (1830) By Percy Bysshe Shelley, p. 216

- ^ Personal reminiscences: by O'Keefe, Kelly, and Taylor By John O'Keeffe, Michael Kelly, John Taylor,1875 (p.249)

- ^ Personal reminiscences: by O'Keefe, Kelly, and Taylor By John O'Keeffe, Michael Kelly, John Taylor, 1875(p.250)

- ^ Personal reminiscences: by O'Keefe, Kelly, and Taylor By John O'Keeffe, Michael Kelly, John Taylor,1875 (p.252)

- ^ As quoted in Representative actors: a collection of criticisms, anecdotes, personal ... By William Clark Russell, 1888, p. 252

- ^ Undoubtedly this change would have influenced his famous abolitionist niece Fanny Kemble, who wrote of him and his wife "Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Kemble, who were excellent, worthy people." in Records of a Girlhood by Fanny Kemble, Vol. 3. p. 19

- ^ Henry Stephen Kemble of Winchester and Trinity College, Cambridge; after playing in the country appeared at the Haymarket, 1814; acted at Bath and Bristol and played Romeo and other leading parts at Drury Lane, 1818-19; afterwards appeared at minor theatres.

- ^ The European Magazine, and the London Review, 1819, p. 49

- ^ Durham Times "Theatre hits a hey day and then a down turn" Friday 2 May 2008

- ^ http://www.royalmint.com/discover/uk-coins/coin-design-and-specifications/two-pound-coin/2013-guinea