Subtraction

Subtraction is a mathematical operation that represents the operation of removing objects from a collection. It is signified by the minus sign (−). For example, in the picture on the right, there are 5 − 2 apples—meaning 5 apples with 2 taken away, which is a total of 3 apples. Therefore, 5 − 2 = 3. Besides counting fruits, subtraction can also represent combining other physical and abstract quantities using different kinds of objects: negative numbers, fractions, irrational numbers, vectors, decimals, functions, matrices and more.

Subtraction follows several important patterns. It is anticommutative, meaning that changing the order changes the sign of the answer. It is not associative, meaning that when one subtracts more than two numbers, the order in which subtraction is performed matters. Subtraction of 0 does not change a number. Subtraction also obeys predictable rules concerning related operations such as addition and multiplication. All of these rules can be proven, starting with the subtraction of integers and generalizing up through the real numbers and beyond. General binary operations that continue these patterns are studied in abstract algebra.

Performing subtraction is one of the simplest numerical tasks. Subtraction of very small numbers is accessible to young children. In primary education, students are taught to subtract numbers in the decimal system, starting with single digits and progressively tackling more difficult problems. Mechanical aids range from the ancient abacus to the modern computer.

Basic subtraction: integers

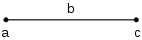

Imagine a line segment of length b with the left end labeled a and the right end labeled c. Starting from a, it takes b steps to the right to reach c. This movement to the right is modeled mathematically by addition:

- a + b = c.

From c, it takes b steps to the left to get back to a. This movement to the left is modeled by subtraction:

- c − b = a.

Now, a line segment labeled with the numbers 1, 2, and 3. From position 3, it takes no steps to the left to stay at 3, so 3 − 0 = 3. It takes 2 steps to the left to get to position 1, so 3 − 2 = 1. This picture is inadequate to describe what would happen after going 3 steps to the left of position 3. To represent such an operation, the line must be extended.

To subtract arbitrary natural numbers, one begins with a line containing every natural number (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, ...). From 3, it takes 3 steps to the left to get to 0, so 3 − 3 = 0. But 3 − 4 is still invalid since it again leaves the line. The natural numbers are not a useful context for subtraction.

The solution is to consider the integer number line (..., −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...). From 3, it takes 4 steps to the left to get to −1:

- 3 − 4 = −1.

Subtraction as addition

| Arithmetic operations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are some cases where subtraction as a separate operation becomes problematic. For example, 3 − (−2) (i.e. subtract −2 from 3) is not immediately obvious from either a natural number view or a number line view, because it is not immediately clear what it means to move −2 steps to the left or to take away −2 apples. One solution is to view subtraction as addition of signed numbers. Extra minus signs simply denote additive inversion. Then we have 3 − (−2) = 3 + 2 = 5. This also helps to keep the ring of integers "simple" by avoiding the introduction of "new" operators such as subtraction. Ordinarily a ring only has two operations defined on it; in the case of the integers, these are addition and multiplication. A ring already has the concept of additive inverses, but it does not have any notion of a separate subtraction operation, so the use of signed addition as subtraction allows us to apply the ring axioms to subtraction without needing to prove anything.

Algorithms for subtraction

There are various algorithms for subtraction, and they differ in their suitability for various applications. A number of methods are adapted to hand calculation; for example, when making change, no actual subtraction is performed, but rather the change-maker counts forward.

For machine calculation, the method of complements is preferred, whereby the subtraction is replaced by an addition in a modular arithmetic.

The teaching of subtraction in schools

This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (December 2013) |

Methods used to teach subtraction to elementary school vary from country to country, and within a country, different methods are in fashion at different times. In what is, in the U.S., called traditional mathematics, a specific process is taught to students at the end of the 1st year or during the 2nd year for use with multi-digit whole numbers, and is extended in either the fourth or fifth grade to include decimal representations of fractional numbers.

Some American schools currently teach a method of subtraction using borrowing or regrouping and a system of markings called crutches.[1] Although a method of borrowing had been known and published in textbooks previously, the use of crutches in American schools spread after William A. Brownell published a study claiming that crutches were beneficial to students using this method.[2] This system caught on rapidly, displacing the other methods of subtraction in use in America at that time.

Some European schools employ a method of subtraction called the Austrian method, also known as the additions method. There is no borrowing in this method. There are also crutches (markings to aid memory), which vary by country.[3][4]

Both these methods break up the subtraction as a process of one digit subtractions by place value. Starting with a least significant digit, a subtraction of subtrahend:

- sj sj−1 ... s1

from minuend

- mk mk−1 ... m1,

where each si and mi is a digit, proceeds by writing down m1 − s1, m2 − s2, and so forth, as long as si does not exceed mi. Otherwise, mi is increased by 10 and some other digit is modified to correct for this increase. The American method corrects by attempting to decrease the minuend digit mi+1 by one (or continuing the borrow leftwards until there is a non-zero digit from which to borrow). The European method corrects by increasing the subtrahend digit si+1 by one.

Example: 704 − 512.

The minuend is 704, the subtrahend is 512. The minuend digits are m3 = 7, m2 = 0 and m1 = 4. The subtrahend digits are s3 = 5, s2 = 1 and s1 = 2. Beginning at the one's place, 4 is not less than 2 so the difference 2 is written down in the result's one place. In the ten's place, 0 is less than 1, so the 0 is increased by 10, and the difference with 1, which is 9, is written down in the ten's place. The American method corrects for the increase of ten by reducing the digit in the minuend's hundreds place by one. That is, the 7 is struck through and replaced by a 6. The subtraction then proceeds in the hundreds place, where 6 is not less than 5, so the difference is written down in the result's hundred's place. We are now done, the result is 192.

The Austrian method does not reduce the 7 to 6. Rather it increases the subtrahend hundred's digit by one. A small mark is made near or below this digit (depending on the school). Then the subtraction proceeds by asking what number when increased by 1, and 5 is added to it, makes 7. The answer is 1, and is written down in the result's hundred's place.

There is an additional subtlety in that the student always employs a mental subtraction table in the American method. The Austrian method often encourages the student to mentally use the addition table in reverse. In the example above, rather than adding 1 to 5, getting 6, and subtracting that from 7, the student is asked to consider what number, when increased by 1, and 5 is added to it, makes 7.

Subtraction by hand

Austrian method

Example:

-

1 + … = 3

-

The difference is written under the line.

-

9 + … = 5

The required sum (5) is too small! -

So, we add 10 to it and put a 1 under the next higher place in the subtrahend.

-

9 + … = 15

Now we can find the difference like before. -

(4 + 1) + … = 7

-

The difference is written under the line.

-

The total difference.

Subtraction from left to right

Example:

-

7 − 4 = 3

This result is only penciled in. -

Because the next digit of the minuend is smaller than the subtrahend, we subtract one from our penciled-in-number and mentally add ten to the next.

-

15 − 9 = 6

-

Because the next digit in the minuend is not smaller than the subtrahend, We keep this number.

-

3 − 1 = 2

American method

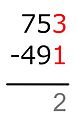

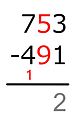

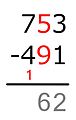

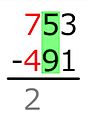

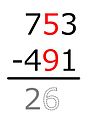

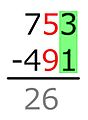

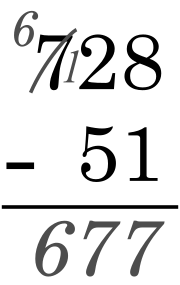

In this method, each digit of the subtrahend is subtracted from the digit above it starting from right to left. If the top number is too small to subtract the bottom number from it, we add 10 to it; this 10 is 'borrowed' from the top digit to the left, which we subtract 1 from. Then we move on to subtracting the next digit and borrowing as needed, until every digit has been subtracted. Example:

-

3 − 1 = …

-

We write the difference under the line.

-

5 − 9 = …

The minuend (5) is too small! -

So, we add 10 to it. The 10 is 'borrowed' from the digit on the left, which goes down by 1.

-

15 − 9 = …

Now the subtraction works, and we write the difference under the line. -

6 − 4 = …

-

We write the difference under the line.

-

The total difference.

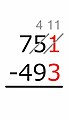

Trade first

A variant of the American method where all borrowing is done before all subtraction.[5]

Example:

-

1 − 3 = not possible.

We add a 10 to the 1. Because the 10 is 'borrowed' from the nearby 5, the 5 is lowered by 1. -

4 − 9 = not possible.

So we proceed as in step 1. -

Working from right to left:

11 − 3 = 8 -

14 − 9 = 5

-

6 − 4 = 2

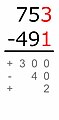

Partial differences

The partial differences method is different from other vertical subtraction methods because no borrowing or carrying takes place. In their place, one places plus or minus signs depending on whether the minuend is greater or smaller than the subtrahend. The sum of the partial differences is the total difference.[6]

Example:

-

The smaller number is subtracted from the greater:

700 − 400 = 300

Because the minuend is greater than the subtrahend, this difference has a plus sign. -

The smaller number is subtracted from the greater:

90 − 50 = 40

Because the minuend is smaller than the subtrahend, this difference has a minus sign. -

The smaller number is subtracted from the greater:

3 − 1 = 2

Because the minuend is greater than the subtrahend, this difference has a plus sign. -

+ 300 − 40 + 2 = 262

Nonvertical methods

Counting up

Instead of finding the difference digit by digit, one can count up the numbers between the subtrahend and the minuend. [7]

Example:

1234 − 567 = can be found by the following steps:

- 567 + 3 = 570

- 570 + 30 = 600

- 600 + 400 = 1000

- 1000 + 234 = 1234

Add up the value from each step to get the total difference: 3 + 30 + 400 + 234 = 667.

Breaking up the subtraction

Another method that is useful for mental arithmetic is to split up the subtraction into small steps.[8]

Example:

1234 − 567 = can be solved in the following way:

- 1234 − 500 = 734

- 734 − 60 = 674

- 674 − 7 = 667

Same change

The same change method uses the fact that adding or subtracting the same number from the minuend and subtrahend does not change the answer. One adds the amount needed to get zeros in the subtrahend.[9]

Example:

"1234 − 567 =" can be solved as follows:

- 1234 − 567 = 1237 − 570 = 1267 − 600 = 667

Units of measurement

When subtracting two numbers with units of measurement such as kilograms or pounds, they must have the same unit. In most cases the difference will have the same unit as the original numbers.

One exception is when subtracting two numbers with percentage as unit. In this case, the difference will have percentage points as unit; the difference is that percentages must be positive, while percentage points may be negative.

See also

References

- ^ Paul Klapper (1916). The Teaching of Arithmetic: A Manual for Teachers. pp. 80–.

- ^ Ross, Susan C.; Pratt-Cotter, Mary (1999). "Subtraction From a Historical Perspective". School Science and Mathematics. 99 (7): 389–393.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Klapper 1916, p. 177-.

- ^ David Eugene Smith (1913). The Teaching of Arithmetic. Ginn. pp. 77–.

- ^ The Many Ways of Arithmetic in UCSMP Everyday Mathematics Subtraction: Trade First

- ^ Partial-Differences Subtraction; The Many Ways of Arithmetic in UCSMP Everyday Mathematics Subtraction: Partial Differences

- ^ The Many Ways of Arithmetic in UCSMP Everyday Mathematics Subtraction: Counting Up

- ^ The Many Ways of Arithmetic in UCSMP Everyday Mathematics Subtraction: Left to Right Subtraction

- ^ The Many Ways of Arithmetic in UCSMP Everyday Mathematics Subtraction: Same Change Rule

Bibliography

- Brownell, W. A. (1939). Learning as reorganization: An experimental study in third-grade arithmetic, Duke University Press.

- Subtraction in the United States: An Historical Perspective, Susan Ross, Mary Pratt-Cotter, The Mathematics Educator, Vol. 8, No. 1 (original publication) and Vol. 10, No. 1 (reprint.) PDF

External links

- "Subtraction", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Printable Worksheets: Subtraction Worksheets, One Digit Subtraction, Two Digit Subtraction, and Four Digit Subtraction

- Subtraction Game at cut-the-knot

- Subtraction on a Japanese abacus selected from Abacus: Mystery of the Bead

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle \left.{\begin{matrix}\scriptstyle {\frac {\scriptstyle {\text{dividend}}}{\scriptstyle {\text{divisor}}}}\\[1ex]\scriptstyle {\frac {\scriptstyle {\text{numerator}}}{\scriptstyle {\text{denominator}}}}\end{matrix}}\right\}\,=\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d5d22ff59234f0d437be740306e8dd905991e1e)

![{\displaystyle \scriptstyle {\sqrt[{\text{degree}}]{\scriptstyle {\text{radicand}}}}\,=\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5582d567e7e7fbcdb728291770905e09beb0ea18)