Sultanate of Damagaram

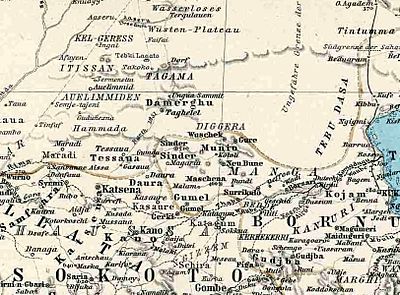

The Sultanate of Damagaram was a muslim pre-colonial state in what is now southeastern Niger, centered on the city of Zinder.

History

Rise

The Sultanate of Damagaram was founded in 1731 (near Myrria, modern Niger) by Muslim Kanouri aristocrats, led by Mallam (r. 1736–1743). Damagaram was at the beginning a vassal state of the decaying Kanem-Bornu Empire. Quickly came to conquer all its fellow vassal states of western Bornu. In the 1830s, the small band of Bornu nobles and retainers conquered the Myrria kingdom, the Sassebaki sultanates (including Zinder). By the 19th century, Damagaram had absorbed 18 Bornu vassal states in the area.

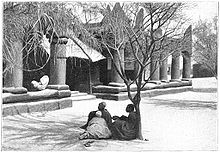

Zinder rose from a small Hausa village to an important center of the Trans-Saharan trade with the moving of the capital of Damagaram there in 1736. The large fortress of the southeast central city (Birini) was built shortly thereafter, and became a major hub for trade south through Kano and east to Bornu. The Hausa town and Zengou, its Tuareg suburb,[1] expanded with this trade.

Apex

Damagaram had a mixed relationship with the other major regional power, the Sokoto Caliphate to the south. While it provided aid to the animist Hausa led refugee states to its west (in what is now Niger) who were formed from the rump of the states conquered by the Sokoto Caliph, Damagaram also maintained good relations with its southern neighbors. Damagaram sat astride the major trade route linking Tripoli to Kano, one of the more powerful Sokoto sultanates, which provided the economic lifeblood of both states. An east west trade from the Niger River to Bornu also passed through Zinder, making relations with animist neighbors like Maradi or the Gobirwa as profitable, and thus important. Damagaram also covered some of the more productive of Bornu's western salt producing evaporation mines, as well as farms producing Ostrich feathers, highly valued in Europe.

In the mid 19th century, European travelers estimated the state covered some 70,000 square kilometers and had a population over 400,000, mostly Hausa, but also Tuareg, Fula, Kanuri, Arab and Toubou. At the center of the state was the royal family, a Sultan (in Hausa the Sarkin Damagaram) with many wives (an estimated 300 wives by visitor Heinrich Barth in 1851) and children, and a tradition of direct (to son or brother) succession which reached 26 rulers by 1906. The sultan ruled through the activities of two primary officers the: Ciroma (Military commander and prime minister) his heir-apparent the Yakudima. By the end of the 19th century, Damagaram could field an army of 5,000 cavalry, 30,000 foot soldiers, and a dozen cannons, which they produced in Zinder. Damagaram could also call upon forces of the allied Kel Gres Tuareg who formed communities near Zinder and other parts of the sultanate.

French conquest

When the French arrived in force in the 1890s, Zinder was the only city of over 10,000 in what is today Niger. Damagaram found itself threatened by well-armed European incursions to the west, and the conquering forces of Rabih az-Zubayr to the east and south. In 1898, A French force under Captain Marius Gabriel Cazemajou spent three weeks under the Sultan's protection in Damagaram. Cazemajou had been dispatched to form an alliance against the British with Rabih, and the Sultan's court were alarmed at the prospect of their two most powerful new threats linking up. Cazemajou was murdered by a faction at the court, and the remainder of the French escaped, protected by other factions. In 1899, the reconstituted elements of the ill-fated Voulet-Chanoine Mission finally arrived in Damagaram on its way to revenge Cazemajou's death. Meeting on 30 July at the Battle of Tirmini, 10 km from Zinder, the well-armed Senegalese-French troops defeated the Sultan and took Damagaram's capital.

With colonialism came the loss of some of Damagaram's traditional lands and its most important trade partner to the British in Nigeria.

The French placed the capital of the new Niger Military Territory there in 1911. In 1926, following fears of Hausa revolts and improving relations with the Djerma of the west, the capital was transferred to the village of Niamey.

The brother of Sultan Ahmadou mai Roumji had earlier sided with the French, and was placed on the throne in 1899 as Sultan Ahamadou dan Bassa. Following French intelligence that a rising by Hausa in the area were preparing a revolt with the aid of the Sultan, a puppet Sultan was placed in power in 1906, though the royal line was restored in 1923. The Sultanate continues to operate in a ceremonial function into the 21st century.

Economy

The wealth of Damagaram depended on three related sources: on taxes and income from the caravan trade, the capture and the exchange of slaves, and internal taxes.

Environmental policies

Damagaram was originally an area of hunting and gathering activities. As the sultanate developed, the rulers encouraged the rural population to expand farming. Most of the land, especially that surrounding the capital Zinder, belonged to the Sultan and a few notables. In all cases, people who held land were obliged to pay an annual tribute to the sultan".

In order to limit the environmental degradation of this conversion to agriculture, the sultan Tanimoune (1854–84) enforced laws to forbid the cutting of certain trees, with particular emphasis on the gawo tree (Faidherbia albida) with its fertilising properties: "He who cuts a gawo tree without authorization will have his head severed; he who mutilates it without reason will have an arm cut off." The sultan and later his successors also proceeded to plant trees, gawo trees in particular, and dispersed the seeds throughout the empire. Other protected trees were aduwa (Balanites aegyptiaca), kurna or magaria (Ziziphus spina-christi and Ziziphus mauritania), madaci dirmi (Khaya senegalensis), magge and gamji (Ficus spp.). The fallow period for land at that time was six years.[2]

The authority that the sultan claimed on trees was a new practice, breaking with customary views on trees in the Sahel. Traditionally, trees were considered 'gifts from the gods' and could not be owned by any individual, but belonged either to the spirits of the bush or to God. The policies of sultan Tanimoune anchored a new perception: they became called the 'trees of the sultan'.

Sultans of Damagaram

The Sultanate of Damagaram has been ruled by the following sultans:[3]

- Mallam Yunus dan Ibram 1731–46

- Baba dan Mallam 1746–57

- Tanimoun Babami 1757–75

- Assafa dan Tanimoun 1775–82

- Abaza dan Tanimoun 1782–87

- Mallam dan Tanimoun Babou Tsaba 1787–90

- Daouda dan Tanimoun 1790–99

- Ahmadou dan Tanimoun Na Chanza 1799–1812

- Sulayman dan Tanimoun 1812–22

- Ibrahim dan Suleyman 1822-41

- Tanimoun dan Suleyman 1841-43

- Ibrahim dan Suleyman (restored) 1843–51

- Tanimoun dan Suleyman (restored) 1851-84

- Abba Gato 1884

- Suleyman dan Aisa 1884-1893

- Amadou dan Tanimoun Mai Roumji Kouran Daga 1893-1899

- Amadou dan Tanimoun dan Bassa 1899-1906

- Ballama (regent) 1906-1923

- Barma Moustapha 1923-1950

- Sanda Oumarou dan Amadou 1950-1978

- Aboubacar Sanda Oumarou 1978-2000

- Mamadou Moustafa 2000-2011

- Aboubacar Sanda Oumarou (restored) 2011–present

See also

Notes

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 985.

- ^ F.W. Sowers and Manzo Issoufou, "Precolonial Agroforestry and its Implications for the Present: the Case of the Sultanate of Damagaram, Niger. Published in: Vandenbeldt, R.J. (ed.) 1992. Faidherbia albida in the West African semi-arid tropics: proceedings of a workshop, 22-26 Apr 1991, Niamey, Niger. (In En. Summaries in En, Fr, Es.) Patancheru, A.P. 502 324, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics; and Nairobi, Kenya: International Centre for Research in Agroforestry. pp 171-175. Template:ISBN 92-9066-220-4.

- ^ Abdourahmane Idrissa & Samuel Decalo, "Damagaram, Sultanate of", in Historical Dictionary of Niger, pp. 160-161

References

- Columbia Encyclopedia:Zinder

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 985.

- James Decalo. Historical Dictionary of Niger. Scarecrow Press/ Metuchen. NJ - London (1979) ISBN 0-8108-1229-0

- Finn Fuglestad. A History of Niger: 1850–1960. Cambridge University Press (1983) ISBN 0-521-25268-7