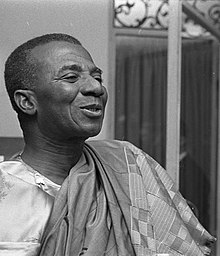

Sylvanus Olympio

Sylvanus Olympio | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Togo | |

| In office 27 April 1960 – 13 January 1963 | |

| Succeeded by | Emmanuel Bodjollé |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 6, 1902 Lomé, Togoland |

| Died | January 13, 1963 (aged 60) Lomé, Togo |

| Political party | Comité de l'unité togolaise |

| Spouse | Dina Olympio (1903-1964) |

Sylvanus Epiphanio Olympio (6 September 1902 – 13 January 1963) was a Togolese politician who served as Prime Minister, and then President, of Togo from 1958 until his assassination in 1963. He came from the important Olympio family, which included his uncle Octaviano Olympio, one of the richest people in Togo in the early 1900s. After graduating from the London School of Economics, he worked for Unilever and became the general manager of the African operations of that company. After World War II, Olympio became prominent in efforts for independence of Togo and his party won the 1958 election making him the Prime Minister of the country. His power was further cemented when Togo achieved independence and he won the 1961 election making him the first President of Togo. He was assassinated during the 1963 Togolese coup d'état.

Early life and business career

Sylvanus Olympio was born on 6 September 1902 in Lomé in the German protectorate of Togoland. He was the grandson to the important Afro-Brazilian trader Francisco Olympio Sylvio[1] and son to Ephiphanio Olympio, who ran the prominent trading house for the Miller Brothers from Liverpool in Agoué (in present-day Benin).[2] His uncle, Octaviano Olympio had located his business in Lomé, which would become the capital of the protectorate, and quickly became one of the richest people in the German and then French colony of Togoland.[2]

His early education was at the German Catholic school in Lomé,[3] which his uncle Octaviano had built for the Society for the Divine Word.[4] Following that, he began study at the London School of Economics,[3] where he studied economics under Harold Laski.[5] Upon graduation, he worked for Unilever first in Nigeria and then in the Gold Coast. By 1929, he was located to be the head of Unilever operations in Togoland.[6] In 1938, he remained in Lomé, but was promoted to become the general manager of the United Africa Company's, then part of Unilever, operations throughout Africa.[7][6]

During World War II, the colony came under the control of the Vichy France government which treated the Olympio family with general suspicion because of their ties to the British.[7] Olympio was arrested in 1942 and held under constant surveillance in the remote city of Djougou in French Dahomey.[7] The imprisonment would permanently change his view toward the French and he would become active in pushing for independence of Togo at the end of the war.[7]

Political career

Olympio became active in the domestic and international struggle to gain independence for Togo following World War II. Since Togo was not formally a French colony, but was a trustee under the rules of the League of Nations and then the United Nations, Olympio petitioned the United Nations Trusteeship Council for a host of issues pushing toward independence.[8] His 1947 petition to the Trusteeship Council was the first petition for resolution of grievances taken to the United Nations.[9] Domestically he founded the Comité de l'unité togolaise (CUT) which became the major party opposing French control over Togo.[6]

Olympio's party boycotted elections during the 1950s within Togo because of heavy French involvement in the elections (including the 1956 election that made Nicolas Grunitzky, the brother to Olympio's wife, the Prime Minister of the colony as head of the Togolese Progress Party). In 1954, Olympio was arrested by the French authorities and his right to vote and run for office were suspended.[3] However, his petitions to the Trusteeship Council led to the 1958 elections where French control over the elections were limited, although involvement remained significant, and Olympio's CUT party was able to win every elected position in the national council.[8] The French were then forced to restore Olympio's right to hold office and he became the Prime Minister of the Togo colony and began pressing for independence.[8][3]

From 1958 until 1961 he served as the Prime Minister of Togo and also served as the Minister of Finance, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Minister of Justice for the colony.[6] He connected with many of the other independence struggles throughout the continent; for example making Ahmed Sékou Touré, first President of Guinea, conseiller special to his government in 1960.[5] In 1961, as part of the transition of power away from French control, the country voted for a President and affirmed the Constitution developed by Olympio and his party. Olympio defeated Grunitzky with over 90% of the vote to become the first president of Togo and the Constitution was approved.[10]

Togo–Ghana relations

One of the defining dynamics during Olympio's Presidency was the tense relationship between Ghana and Togo. Kwame Nkrumah and Olympio were initially allies working together to gain independence for their neighboring countries; however, the two leaders split when fighting over the eastern part of the German colony which had become part of the British Gold Coast and eventually part of Ghana. The division resulted in splitting up the land of the Ewe people. Nkrumah proposed openly that Togo become part of Ghana while Olympio sought to have the eastern part of the German colony returned to Togo. The relationship became quite tense with Olympio referring to Nkrumah as a "black imperialist" and Nkrumah repeatedly threatening Olympio's government.[3]

Relations between the two countries became very tense after 1961 with multiple assassination attempts against each leader resulting in accusations against the other leader and domestic repression leading to refugees receiving support from the other country. Exiles opposing Nkrumah organized in Togo and exiles opposing Olympio organized in Ghana creating a very tense atmosphere.[11]

Togo–France relations

The French initially treated Olympio with significant hostility during the transition to independence and later, after Olympio became the President in 1961, the French became concerned that Olympio was largely aligned with British and American interests.[12] Olympio adopted a unique position for early independent African leaders of former French territories. Although he tried to rely on little foreign aid, when necessary he relied on German aid rather than French aid. He was not part of the alliances between France and their ex-colonies (notably not joining the African and Malagasy Union) and fostered connections with former British colonies (namely Nigeria) and the United States.[5] Eventually, he began to improve relations with France and when relations with Ghana were at their most tense, he secured a defense pact with the French in order to ensure protection for Togo.[5]

Domestic politics

Domestic politics was largely defined by Olympio's efforts to restrain spending and develop his country without being reliant on outside support and repression of opposition parties.

His austere spending was most significant in the realm of military policy. Initially, Olympio had pushed for Togo to have no military when it achieved independence, but with threats from Nkrumah being a concern, he agreed to a small military (only about 250 soldiers).[3][13] However, an increasing number of French troops began returning to their homes in Togo and were not provided enlistment in the limited Togolese military because of its small size. Emmanuel Bodjolle and Kléber Dadjo, the leaders in the Togo military, repeatedly tried to get Olympio to increase funding and enlist more of the ex-French army troops returning to the country, but were unsuccessful.[13] On 24 September 1962, Olympio rejected the personal plea by Étienne Eyadéma, a Sergent in the French military, to join the Togolese military.[14] On 7 January 1963, Dadjo again presented a request for enlisting ex-French troops[14] and Olympio reportedly tore up the request.[13]

At the same time, Togo largely became a one-party state during Olympio's presidency. Following a 1961 unsuccessful attempt on Olympio's life in which Grunitzky's Togolese Progress Party and the Juvento movement under Antoine Meatchi were accused, the opposition was outlawed. Meatchi was imprisoned for a brief period before being exiled and other opposition leaders left the country. The result was that Olympio maintained a significant amount of authority and his party dominated political life.[15]

Foreign policy

Olympio largely pursued a policy of connecting Togo with Britain, the United States and other Western Bloc countries. In 1962, he visited the United States and had a friendly meeting with President John F. Kennedy.[16] In many respects, he was a cultural linkage between British and French west Africa and spoke both languages fluently and connected with the elites in both circles.[17]

Assassination

Shortly after midnight on 13 January 1963, Olympio and his wife were awakened by many members of the military breaking into their house. Before dawn, Olympio's body was discovered by the U.S. Ambassador Leon B. Poullada three feet from the door to the U.S. Embassy.[11] It was the first coup d'état in the French and British colonies in Africa that achieved independence in the 1950s and 1960s,[18] and Olympio is remembered as the first President to be assassinated during a military coup in Africa.[19] Étienne Eyadéma, who would claim power in 1967 and remain in office until 2005, claimed to have personally fired the shot that killed Olympio while Olympio tried to escape.[20] Emmanuel Bodjollé became the head of the government for two days until the military created a new government headed by Nicolas Grunitzky, as President, and Antoine Meatchi, as Vice President.[21]

The assassination sent shock waves throughout Africa. Guinea, Liberia, the Ivory Coast, and Tanganyika all denounced the coup and the assassination, while only Senegal and Ghana (and to a lesser extent Benin) recognized the government of Grunitzky and Meatchi until elections in May. The government of Togo was excluded from the Addis Ababa Conference which formed the Organisation of African Unity later that year as a result of the coup.[22]

Aftermath

The army increased dramatically from 250 in 1963 to 1,200 by 1966.[13] And when protests in the Ewe region, Olympio's ethnic group, caused chaos in 1967, the military under Étienne Eyadéma deposed the government of Nicolas Grunitzky.[21] Eyadéma ruled the country from 1967 until 2005. Olympio's family remained in exile for much of that period and only returned to the country with democratic openings at the end of Eyadéma's rule. Olympio's son, Gilchrist Olympio, is the head of the party Union of Forces for Change and has led the main opposition in Togo since the mid-1990s.

References

- ^ Amos 2001, p. 295.

- ^ a b Amos 2001, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d e f New York Times 1960, p. 11.

- ^ Amos 2001, p. 299.

- ^ a b c d Howe 2000, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Washington Post 1960, p. E4.

- ^ a b c d Amos 2001, p. 308.

- ^ a b c Howe 2000, p. 45.

- ^ New York Amsterdam News 1947, p. 1.

- ^ New York Times 1961, p. 6.

- ^ a b Washington Post 1963, p. A11.

- ^ New African 1999, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Grundy 1968, p. 437.

- ^ a b Lukas 1963, p. 3.

- ^ Rothermund 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Statement by the President on the Death of President Sylvanus Olympio of Togo

- ^ Mazuri 1968, p. 56.

- ^ Howe 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Mazuri 1968, p. 57.

- ^ Gnassingbe Eyadema Obituary

- ^ a b Onwumechili 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Wallerstein 1961, p. 64.

Bibliography

Books and Journals

- Amos, Alcione M. (2001). "Afro-Brazilians in Togo: The Case of the Olympio Family, 1882-1945". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 41 (162): 293–314. doi:10.4000/etudesafricaines.88. JSTOR 4393131.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grundy, Kenneth W. (1968). "The Negative Image of Africa's Military". The Review of Politics. 30 (4): 428–439. doi:10.1017/s003467050002516x. JSTOR 1406107.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howe, Russell Warren (2000). "Men of the Century". Transition (86): 36–50. JSTOR 3137463.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mazuri, Ali A. (1968). "Thoughts on Assassination in Africa". Political Science Quarterly. 83 (1): 40–58. JSTOR 2147402.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Onwumechili, Chuka (1998). African Democratization and Military Coups. Westport, Ct.: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-96325-5. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rothermund, Dietmar (2006). The Routledge Companion To Decolonization. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-35632-9. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wallerstein, Immanuel (1961). Africa: The Politics of Independence And Unity. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9856-9. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Newspapers (organized chronologically)

- "Protest Speech Sets UN Record". New York Amsterdam News. 13 December 1947. p. 1.

- "Energetic Togo Leader: Sylvanus Olympio". New York Times. 8 April 1960. p. 11.

- "A Robust Leader Speaks for Togo". Washington Post. 1 May 1960. p. E4.

- "Togo backs Olympio: Returns show 99% Support Ex-Premier as President". New York Times. 11 April 1961. p. 6.

- "Togo's President Slain in Coup: Insurgents Seize Most Of Cabinet". The Washington Post. 14 January 1963. p. A1.

- Lukas, J. Anthony (22 January 1963). "Olympio Doomed by Own Letter: Sergent whose job appeal failed slew Togo Head". New York Times. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "France and the Olympios". New African. No. 377. September 1999. p. 13.

- Presidents of Togo

- Prime Ministers of Togo

- 1902 births

- 1963 deaths

- People of French West Africa

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Assassinated heads of government

- Assassinated heads of state

- Assassinated Togolese politicians

- Togolese people of Brazilian descent

- Togolese people of Ghanaian descent

- People murdered in Togo

- Alumni of the London School of Economics

- Togolese politicians

- 1960 in French Togoland

- 1960s in Togo

- 1963 in Togo

- 20th-century rulers in Africa