Syntax (programming languages)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

In computer science, the syntax of a computer language is the set of rules that defines the combinations of symbols that are considered to be a correctly structured document or fragment in that language. This applies both to programming languages, where the document represents source code, and markup languages, where the document represents data. The syntax of a language defines its surface form.[1] Text-based computer languages are based on sequences of characters, while visual programming languages are based on the spatial layout and connections between symbols (which may be textual or graphical). Documents that are syntactically invalid are said to have a syntax error.

Syntax – the form – is contrasted with semantics – the meaning. In processing computer languages, semantic processing generally comes after syntactic processing, but in some cases semantic processing is necessary for complete syntactic analysis, and these are done together or concurrently. In a compiler, the syntactic analysis comprises the frontend, while semantic analysis comprises the backend (and middle end, if this phase is distinguished).

Levels of syntax

Computer language syntax is generally distinguished into three levels:

- Words – the lexical level, determining how characters form tokens;

- Phrases – the grammar level, narrowly speaking, determining how tokens form phrases;

- Context – determining what objects or variables names refer to, if types are valid, etc.

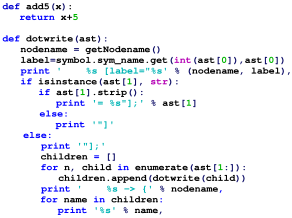

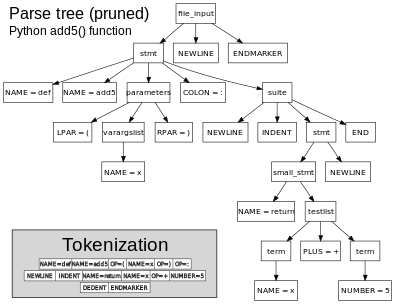

Distinguishing in this way yields modularity, allowing each level to be described and processed separately, and often independently. First a lexer turns the linear sequence of characters into a linear sequence of tokens; this is known as "lexical analysis" or "lexing". Second the parser turns the linear sequence of tokens into a hierarchical syntax tree; this is known as "parsing" narrowly speaking. Thirdly the contextual analysis resolves names and checks types. This modularity is sometimes possible, but in many real-world languages an earlier step depends on a later step – for example, the lexer hack in C is because tokenization depends on context. Even in these cases, syntactical analysis is often seen as approximating this ideal model.

The parsing stage itself can be divided into two parts: the parse tree or "concrete syntax tree" which is determined by the grammar, but is generally far too detailed for practical use, and the abstract syntax tree (AST), which simplifies this into a usable form. The AST and contextual analysis steps can be considered a form of semantic analysis, as they are adding meaning and interpretation to the syntax, or alternatively as informal, manual implementations of syntactical rules that would be difficult or awkward to describe or implement formally.

The levels generally correspond to levels in the Chomsky hierarchy. Words are in a regular language, specified in the lexical grammar, which is a Type-3 grammar, generally given as regular expressions. Phrases are in a context-free language (CFL), generally a deterministic context-free language (DCFL), specified in a phrase structure grammar, which is a Type-2 grammar, generally given as production rules in Backus–Naur Form (BNF). Phrase grammars are often specified in much more constrained grammars than full context-free grammars, in order to make them easier to parse; while the LR parser can parse any DCFL in linear time, the simple LALR parser and even simpler LL parser are more efficient, but can only parse grammars whose production rules are constrained. Contextual structure can in principle be described by a context-sensitive grammar, and automatically analyzed by means such as attribute grammars, though in general this step is done manually, via name resolution rules and type checking, and implemented via a symbol table which stores names and types for each scope.

Tools have been written that automatically generate a lexer from a lexical specification written in regular expressions and a parser from the phrase grammar written in BNF: this allows one to use declarative programming, rather than need to have procedural or functional programming. A notable example is the lex-yacc pair. These automatically produce a concrete syntax tree; the parser writer must then manually write code describing how this is converted to an abstract syntax tree. Contextual analysis is also generally implemented manually. Despite the existence of these automatic tools, parsing is often implemented manually, for various reasons – perhaps the phrase structure is not context-free, or an alternative implementation improves performance or error-reporting, or allows the grammar to be changed more easily. Parsers are often written in functional languages, such as Haskell, in scripting languages, such as Python or Perl, or in C or C++.

Examples of errors

As an example, (add 1 1) is a syntactically valid Lisp program (assuming the 'add' function exists, else name resolution fails), adding 1 and 1. However, the following are invalid:

(_ 1 1) lexical error: '_' is not valid (add 1 1 parsing error: missing closing ')' (add 1 x) name error: 'x' is not bound

Note that the lexer is unable to identify the error – all it knows is that, after producing the token LEFT_PAREN, '(' the remainder of the program is invalid, since no word rule begins with '_'. At the parsing stage, the parser has identified the "list" production rule due to the '(' token (as the only match), and thus can give an error message; in general it may be ambiguous. At the context stage, the symbol 'x' exists in the syntax tree, but has not been defined, and thus the context analyzer can give a specific error.

In a strongly typed language, type errors are also a form of syntax error which is generally determined at the contextual analysis stage, and this is considered a strength of strong typing. For example, the following is syntactically invalid Python code (as these are literals, the type can be determined at parse time):

'a' + 1

…as it adds a string and an integer. This can be detected at the parsing (phrase analysis) level if one has separate rules for "string + string" and "integer + integer", but more commonly this will instead be parsed by a general rule like "LiteralOrIdentifier + LiteralOrIdentifier" and then the error will be detected at contextual analysis stage, where type checking occurs. In some cases this validation is not done, and these syntax errors are only detected at runtime.

In a weakly typed language, where type can only be determined at runtime, type errors are instead a semantic error, and can only be determined at runtime. The following Python code:

a + b

is ambiguous, and while syntactically valid at the phrase level, it can only be validated at runtime, as variables do not have type in Python, only values do.

Syntax definition

The syntax of textual programming languages is usually defined using a combination of regular expressions (for lexical structure) and Backus–Naur Form (for grammatical structure) to inductively specify syntactic categories (nonterminals) and terminal symbols. Syntactic categories are defined by rules called productions, which specify the values that belong to a particular syntactic category.[1] Terminal symbols are the concrete characters or strings of characters (for example keywords such as define, if, let, or void) from which syntactically valid programs are constructed.

A language can have different equivalent grammars, such as equivalent regular expressions (at the lexical levels), or different phrase rules which generate the same language. Using a broader category of grammars, such as LR grammars, can allow shorter or simpler grammars compared with more restricted categories, such as LL grammar, which may requires longer grammars with more rules. Different but equivalent phrase grammars yield different parse trees, though the underlying language (set of valid documents) is the same.

Example: Lisp

Below is a simple grammar, defined using the notation of regular expressions and Backus–Naur Form. It describes the syntax of Lisp, which defines productions for the syntactic categories expression, atom, number, symbol, and list:

expression ::= atom | list

atom ::= number | symbol

number ::= [+-]?['0'-'9']+

symbol ::= ['A'-'Z''a'-'z'].*

list ::= '(' expression* ')'

This grammar specifies the following:

- an expression is either an atom or a list;

- an atom is either a number or a symbol;

- a number is an unbroken sequence of one or more decimal digits, optionally preceded by a plus or minus sign;

- a symbol is a letter followed by zero or more of any characters (excluding whitespace); and

- a list is a matched pair of parentheses, with zero or more expressions inside it.

Here the decimal digits, upper- and lower-case characters, and parentheses are terminal symbols.

The following are examples of well-formed token sequences in this grammar: '12345', '()', '(a b c232 (1))'

Complex grammars

The grammar needed to specify a programming language can be classified by its position in the Chomsky hierarchy. The phrase grammar of most programming languages can be specified using a Type-2 grammar, i.e., they are context-free grammars,[2] though the overall syntax is context-sensitive (due to variable declarations and nested scopes), hence Type-1. However, there are exceptions, and for some languages the phrase grammar is Type-0 (Turing-complete).

In some languages like Perl and Lisp the specification (or implementation) of the language allows constructs that execute during the parsing phase. Furthermore, these languages have constructs that allow the programmer to alter the behavior of the parser. This combination effectively blurs the distinction between parsing and execution, and makes syntax analysis an undecidable problem in these languages, meaning that the parsing phase may not finish. For example, in Perl it is possible to execute code during parsing using a BEGIN statement, and Perl function prototypes may alter the syntactic interpretation, and possibly even the syntactic validity of the remaining code.[3] Colloquially this is referred to as "only Perl can parse Perl" (because code must be executed during parsing, and can modify the grammar), or more strongly "even Perl cannot parse Perl" (because it is undecidable). Similarly, Lisp macros introduced by the defmacro syntax also execute during parsing, meaning that a Lisp compiler must have an entire Lisp run-time system present. In contrast C macros are merely string replacements, and do not require code execution.[4][5]

Syntax versus semantics

The syntax of a language describes the form of a valid program, but does not provide any information about the meaning of the program or the results of executing that program. The meaning given to a combination of symbols is handled by semantics (either formal or hard-coded in a reference implementation). Not all syntactically correct programs are semantically correct. Many syntactically correct programs are nonetheless ill-formed, per the language's rules; and may (depending on the language specification and the soundness of the implementation) result in an error on translation or execution. In some cases, such programs may exhibit undefined behavior. Even when a program is well-defined within a language, it may still have a meaning that is not intended by the person who wrote it.

Using natural language as an example, it may not be possible to assign a meaning to a grammatically correct sentence or the sentence may be false:

- "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously." is grammatically well formed but has no generally accepted meaning.

- "John is a married bachelor." is grammatically well formed but expresses a meaning that cannot be true.

The following C language fragment is syntactically correct, but performs an operation that is not semantically defined (because p is a null pointer, the operations p->real and p->im have no meaning):

complex *p = NULL;

complex abs_p = sqrt (p->real * p->real + p->im * p->im);

More simply:

int x;

printf("%d", x);

is syntactically valid, but not semantically defined, as it uses an uninitialized variable.

See also

To quickly compare syntax of various programming languages, take a look at the list of "Hello, world!" program examples:

- Perl syntax

- PHP syntax and semantics

- C syntax

- C++ syntax

- Java syntax

- JavaScript syntax

- Python syntax and semantics

References

- ^ a b Friedman, Daniel P.; Mitchell Wand; Christopher T. Haynes (1992). Essentials of Programming Languages (1st ed.). The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06145-7.

- ^ Michael Sipser (1997). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 0-534-94728-X. Section 2.2: Pushdown Automata, pp.101–114.

- ^ The following discussions give examples:

- ^ "An Introduction to Common Lisp Macros". Apl.jhu.edu. 1996-02-08. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ "The Common Lisp Cookbook - Macros and Backquote". Cl-cookbook.sourceforge.net. 2007-01-16. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

External links

- Various syntactic constructs used in computer programming languages