Temple of Venus and Roma

Temple of Venus and Roma seen from the Colosseum | |

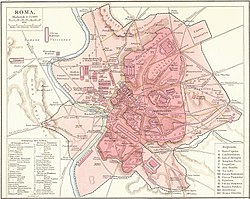

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regio IV Templum Pacis |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′27″N 12°29′23″E / 41.89083°N 12.48972°E |

| Type | Roman temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Hadrian |

| Founded | 135 AD |

The Temple of Venus and Roma (Latin: Templum Veneris et Romae) is thought to have been the largest temple in Ancient Rome. Located on the Velian Hill, between the eastern edge of the Forum Romanum and the Colosseum, it was dedicated to the goddesses Venus Felix ("Venus the Bringer of Good Fortune") and Roma Aeterna ("Eternal Rome").

The building was the creation of the emperor Hadrian and construction began in 121. It was officially inaugurated by Hadrian in 135, and finished in 141 under Antoninus Pius. Damaged by fire in 307,[1] it was restored with alterations by the emperor Maxentius.

History

[edit]The temple was erected on the remains of the Domus Transitoria and Domus Aurea, two mansions commissioned by the disgraced Emperor Nero. Buried intact beneath the temple is an elaborate domed rotunda from the Domus Transitoria, with marble-lined pools and paving in multicoloured opus sectile.[2]

Unimpressed by Hadrian's architectural design for the temple, his most brilliant architect, Apollodorus, made a scornful remark on the size of the seated statues within the cellae, saying that they would surely hurt their heads if they tried to stand up from their thrones. Apollodorus was banished and executed not long after this.[3]

According to the ancient historian Ammianus Marcellinus, the temple was among the great buildings of Rome which astonished the Emperor Constantius II on his visit to the city in 357.[4]

The sanctuary was closed during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire.[citation needed] Restoration was performed under the short-lived usurper Eugenius (392–394), a Christian sympathetic to pagan worship. However, as with many of Rome's majestic ancient buildings, the temple was later targeted for its rich materials. In 630, with the consent of the Emperor Heraclius, Pope Honorius I removed the gilt-bronze tiles from the roof of the temple for the adornment of St. Peter's.[5]

A severe earthquake at the beginning of the 9th century is believed to have destroyed the temple. Around 850 Pope Leo IV ordered the building of a new church, Santa Maria Nova, on the ruins of the temple. After a major rebuilding in 1612, this church was renamed Santa Francesca Romana, incorporating Roma's cella as the belltower. A somewhat fanciful veduta engraving by Giovanni Battista Mercati depicts the site in 1629. The vast quantity of marble that once adorned the temple has all but disappeared due to its use as a raw material for building projects from the Middle Ages onwards. The Italian archaeologist Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani makes reference to his discovery of a lime kiln in close proximity to the temple in his work The Destruction of Ancient Rome”.

Architecture

[edit]

It was set on a platform measuring 145 metres (476 ft) x 100 metres (330 ft). The peripteral temple itself measured 110 metres (360 ft) x 53 metres (174 ft) and 31 metres (102 ft) high (counting the statues) and consisted of two main chambers (cellae), each housing a cult statue of a god—Venus, the goddess of love, and Roma, the goddess of Rome, both figures seated on a throne. The cellae were arranged symmetrically back-to-back. Roma's cella faced west, looking out over the Forum Romanum, and Venus' cella faced east, looking out over the Colosseum. A row of four columns (tetrastyle) lined the entrance to each cella, and the temple was bordered by colonnaded entrances ending in staircases that led down to the Colosseum. As an additional clever subtlety by Hadrian, Venus also represented love (Amor in Latin), and "AMOR" is "ROMA" spelled backwards. Thus, placing the two divinities of Venus and Rome back-to-back in a single temple created a further symmetry with the back-to-back symmetry of their names. Within Venus' cella was another altar where newly wed couples could make sacrifices. Directly adjacent to this altar stood gigantic silver statues of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina the Younger.

The west and east sides of the temple (the short sides) had ten white marble columns (decastyle) while the south and north sides featured twenty columns. All of these columns measured 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) in width, making the temple very imposing.

Most of the remains are incorporated in the church of S.Francesca Romana. Due to the rebuilding by Maxentius, a coffered vaulted ceiling replaced the original wooden roof and the walls were doubled in thickness to take the increased load. The walls were inset with niches with small statues between small red porphyry columns standing above the floor on a plinth, all fronted by a colonnade in red porphyry.[6]

Today

[edit]

Since the papacy of John Paul II, the heights of the temple and its position opposite the main entrance to the Colosseum have been used to good effect as a public address platform. This may be seen in the photograph at right where a red canopy has been erected to shelter the Pope as well as an illuminated cross, on the occasion of the Good Friday ceremony. The Pope, either personally or through a representative, leads the faithful through meditations on the stations of the cross while a cross is carried from there to the Colosseum.

The Temple has now been reopened to the public after an extensive restoration programme that lasted 26 years.[7] Access to the temple is included in tickets for the Colosseum, the Forum and the Palatine Hill.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Dyson, Stephen L. (2010). Rome : a living portrait of an ancient city. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-8018-9253-0.

- ^ John Bryan Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture, Yale University Press, 1994. p 57, ISBN 0140561455

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History, 69.4

- ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1901) The Destruction of Ancient Rome

- ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1901) The Destruction of Ancient Rome

- ^ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 114

- ^ "Ancient Rome's Temple of Venus reopens | Wanted WorldWide". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-11-16.

References

[edit]- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro. 1987. Hadrian and the City of Rome. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Brown, Frank Edward. 1964. “Hadrianic Architecture.” In Essays in Memory of Karl Lehmann, Edited by Lucy F. Sandler. Marsyas, Stud. in the Hist. of Art Suppl.; I, 55–58. New York: Inst. of Fine Arts New York Univ.

- Henderson, L. E. 1936. “The Temple of Venus and Roma.” The Classical Bulletin CII: 1–62.

- Lorenzatti, Sandro (1990). "Vicende del tempio di Venere e Roma nel Medioevo e nel Rinascimento". Rivista dell'Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e storia dell'Arte (13): 119–138.

- Jacobson, David M. 1986. “Hadrianic Architecture and Geometry.” American Journal of Archaeology XC: 69–85.

- Ng, Diana Y. and Molly Swetnam-Burland eds. 2018. Reuse and Renovation in Roman Material Culture: Functions, Aesthetics, Interpretations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stamper, John. 2005. The Architecture of Roman Temples: The Republic to the Middle Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Ziemssen, Hauke. 2006. “Maxentius and the City of Rome: Imperial Building Policy in an Urban Context.” In Common Ground: Archaeology, Art, Science, and Humanities: Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Boston, August 23–26, 2003, Edited by Carol C. Mattusch, Alice A. Donohue, and Amy Brauer, 400–404. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

External links

[edit]- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Temple of Venus and Roma | Art Atlas