The Carpetbaggers (film)

| The Carpetbaggers | |

|---|---|

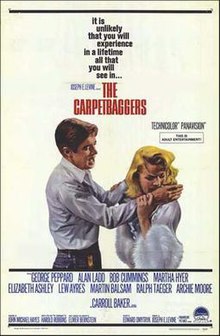

U.S. poster art | |

| Directed by | Edward Dmytryk |

| Screenplay by | John Michael Hayes |

| Based on | The Carpetbaggers by Harold Robbins |

| Produced by | Joseph E. Levine |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph MacDonald |

| Edited by | Frank Bracht |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 150 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.3 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $40 million[2] |

The Carpetbaggers is a 1964 American drama film directed by Edward Dmytryk, based on the best-selling 1961 novel The Carpetbaggers by Harold Robbins and starring George Peppard as Jonas Cord, a character based loosely on Howard Hughes, and Alan Ladd in his last role as Nevada Smith, a former Western gunslinger turned actor. The supporting cast features Carroll Baker as a character extremely loosely based on Jean Harlow as well as Martha Hyer, Bob Cummings, Elizabeth Ashley, Lew Ayres, Ralph Taeger, Leif Erickson, Archie Moore and Tom Tully.

The film is a landmark of the sexual revolution of the 1960s, venturing further than most films of the period with its heated sexual embraces, innuendo, and sadism between men and women, much like the novel, where author Dawn Sova asserts "there is sex and/or sadism every 17 pages".[3]

Plot

[edit]

Jonas Cord Jr. becomes one of America's richest men in the early twentieth century, inheriting an explosives company from his late father, Jonas Cord Sr. Cord buys up all the company stock and pays off his father's young widow, Rina Marlowe.

Cord becomes an aviation pioneer and his wealth grows. He destroys a business rival named Winthrop, then seduces and marries the man's daughter Monica, only to abandon her when she wants to settle down and have a home and children. Monica hangs on for years, aware of Cord's troubled youth, hoping he'll come back to her.

In order to force the divorce, Cord reconnects with his stepmother Rina and begins an affair with her. Crushed, Monica gives Cord his divorce, then discovers she is pregnant with his child. After the birth, Cord visits her, demanding to know if he is the father. Monica tells him to leave her and their newborn daughter alone.

Meanwhile, former Cord company stockholder Nevada Smith finds work in western films, becoming a popular cowboy hero. Rina persuades Cord to finance Nevada's project, a script about his former outlaw life, in which he will star. This gives Cord an interest in the second-rate studio that produces Nevada's films, plus creative control over the resulting movie.

The film becomes successful despite Cord's constant interference. Rina becomes a big star; her career blossoms while Nevada's declines. To spite Cord, Rina marries Nevada, now considered a has-been.

Rina dies in a drunken car crash and Cord's studio is sold out from under him by Dan Pierce, a renegade employee loyal to the old management. After an alcoholic binge, Cord returns to the studio and builds up a film career for the studio's new discovery, Jennie Denton. Denton and Cord begin an affair and become engaged.

With news of the engagement, Dan Pierce tries to blackmail Jennie with a copy of a pornographic film she made in her youth. Jennie confesses to Cord, who laughs, saying he knows all about her past and that he made her a star in order to have her services all to himself. With her dream of love shattered, Jennie runs out devastated.

Seeing the wreckage of both their lives, Nevada Smith confronts Cord and the two end up in a vicious fist-fight. During the brawl, Nevada forces Cord to confront the mess he has made of his own life and those around him. A contrite Cord returns to Monica and begs her to take him back. Monica, who has always loved him, forgives him and they embrace.

Cast

[edit]- George Peppard as Jonas Cord

- Alan Ladd as Nevada Smith

- Carroll Baker as Rina Marlowe

- Bob Cummings as Dan Pierce

- Martha Hyer as Jennie Denton

- Elizabeth Ashley as Monica Winthrop

- Lew Ayres as "Mac" McAllister

- Martin Balsam as Bernard B. Norman

- Ralph Taeger as Buzz Dalton

- Archie Moore as Jedediah

- Leif Erickson as Jonas Cord Sr.

- Arthur Franz as Morrissey, airplane designer at Jonas' company

- Tom Tully as Amos Winthrop, Monica's father and Jonas' business rival

- Audrey Totter as middle-aged prostitute attending to Jonas' week-long drinking binge

- Anthony Warde as Moroni, president of Pioneer National Trust Company of Los Angeles

- Charles Lane as Eugene Denby, Jonas Cord Sr.'s secretary

- Tom Lowell as David Woolf, Bernard Norman's nephew and assistant

- John Conte as Ed Ellis, director of Rina's film at Norman Studio

- Vaughn Taylor as doctor certifying the death of Jonas Cord Sr.

- Francesca Bellini as Cynthia Randall, Norman's mistress and star at Norman Studio

- Victoria Jean as Jo Ann, daughter of Jonas and Monica

Production

[edit]Producer Joseph E. Levine initially claimed he would disregard the Production Code in making his adaptation of Robbins' book. However, when he struck a production deal with Paramount Pictures in 1963, there was no question that the movie would abide by the Code, though he engaged in extensive negotiations with Production Code Administration to get as much salacious content as he could into the film. After haggling with chief censor Geoffrey Shurlock over a nude scene in the script, Levine gave the greenlight to filming it with Caroll Baker in the nude. The nude scene was used for publicity purposes, but only appeared in the European release; an alternate version where Baker is wearing a robe was used in the North American version.[4]

John Michael Hayes signed to write the script in June 1962.[5] (Soon after, Embassy signed him to adapt Where Love Has Gone.[6])

Sonny Tufts was a candidate to play Nevada Smith,[7] losing out to Alan Ladd. When Ladd signed to play Nevada Smith, it was also announced that Paramount and Levine would make a prequel about Smith's adventures called Nevada Smith.[8]

Joan Collins, in her autobiography, Past Imperfect (1978), says she had a firm offer to play Rina Marlowe but had to decline because of pregnancy.

Robert Cummings was cast as an agent. His wife said "years ago Alfred Hitchcock told him he'd made a great villain with that baby face. It's a wonderful change of pace."[9]

Filming started on June 4, 1963.[10]

Nude scene

[edit]Carroll Baker had a highly publicized nude scene, shot on a closed set.[11]

A 1964 New York Times article quoted Baker defending her appearing in the nude. Speaking of her character, Baker said:

“She is alone in front of her dressing table. She has just stepped out of the bath and she is the kind of character to whom it would not occur to put on a robe. Doing the scene in the nude was my idea and I think it was a mistake not to show it.”[12]

Though not in the American release, the nude scene received wide-spread publicity and made the film notorious. The Screen Actors Guild contract prohibited nudity at the time. Baker denied that the nude scene was a publicity gimmick.[12]

Release and reception

[edit]

The Carpetbaggers premiered in Denver, Colorado on April 9, 1964,[13] and went on to be a large commercial success. It grossed $28,409,547 at the domestic box office,[14] making it the fourth highest-grossing film of 1964. Variety reported that the film earned $13 million in domestic rentals. The film grossed $40,000,000 in worldwide box office receipts, against a $3 million budget.[2] It was the peak of Peppard's career as a movie star.[15]

Reviews

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times panned the film as "a sickly sour distillation of Harold Robbins's big-selling novel", with the protagonist "a thoroughly mechanical movie puppet, controlled by a script-writer's strings", and Peppard's performance "expressionless, murky and dull."[16]

Variety wrote, "Psychological facets of the story are fuzzy, and vital motivational information is withheld to the point where it no longer really seems to matter why he is the miserable critter he is. His sudden reform is little more than an unconvincing afterthought. There's nobody to root for in 'The Carpetbaggers.' And Hayes' screenplay never seems to miss an opportunity to slip in connotations of sex, whether or not they are necessary."[17]

Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film "is trash, but it has the curiosity pull of a trashy novel. One sits there squirming in the captive presence of its unremitting boldness and bad taste for two-and-a-half hours (it ends again and again and starts up again and again), waiting only for its central figure, Jonas Cord Jr., to be cornered and stomped on like the rat he is. But then we find him, hat in hand, seeking forgiveness and reconciliation from a wronged ex-wife. More—he gets them."[18] Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post described the film as "wild, fruity nonsense" and observed, "At all events, Robbins and Hayes have it beautifully tied up psychologically and all I can say is that I'm glad I never had an insane twin."[19]

The film became one of the targets for the negative impact of films on society. Crowther cited the film, along with Kiss Me, Stupid, for giving American movies the reputation of "deliberate and degenerate corruptors of public taste and morals".[20]

The movie was one of the 13 most popular films in the UK in 1965.[21] However, many British critics frowned upon the film, considering it to be "vulgar and tasteless" or "an upscale dirty movie".[20][22] The Monthly Film Bulletin stated, "They don't make movies like this any more—or at least, like The Carpetbaggers should have been. Dmytryk does a very clean, efficient job of direction, interweaving the various strands of his complicated story with exemplary clarity, but somehow there is an element missing: the film is big, bold, sprawlingly epic and all that, but it never manages to carry off its outrageous silliness with any of the flourish of the good old days."[23]

Filmink magazine wrote Cummings played "a magnificently slimy agent – slightly effeminate, aging, with a wicked glint in his eye: it’s a terrific performance."[24]

Awards and honors

[edit]For her role as Monica, Elizabeth Ashley received BAFTA and Golden Globe awards nominations for Best Supporting Actress.

Soundtrack

[edit]Elmer Bernstein re-recorded the music from the film for an album released by Ava Records. In 2013 Intrada Records issued the complete original soundtrack on CD, pairing it with the CD premiere of the Ava re-recording (tracks 22-31).

- Seal / Main Title 2:26

- A Maverick 0:52

- Rina's Record 3:32

- The Forbidden Room 2:42

- Sierra Source (Alternate) 1:41

- Sierra Source 2:39

- Separate Trails 2:03

- Monica's Shimmy 0:31

- Lots of Lovely Ceilings 2:02

- Nevada's Trouble 7:12

- Get a Divorce 1:35

- Movie Mogul 0:35

- Two of a Kind 5:11

- Sierra Source Pt. 2 2:14

- Rina's Dead 1:02

- Speak of the Devil 1:29

- New Star 3:05

- Bad Bargain 0:51

- Jonas Hits Bottom 5:40

- Finale 1:26

- Love Theme from The Carpetbaggers 3:10

- The Carpetbaggers 2:31

- Love Theme from The Carpetbaggers 2:40

- Speak of the Devil 2:01

- Forbidden Room 2:19

- The Carpetbagger Blues 3:52

- Main Title from The Carpetbaggers 2:10

- New Star 2:16

- The Producer Asks for a Divorce 2:39

- Jonas Hits Bottom 2:50

- Finale 1:44

Bernstein's theme song was also recorded by Jimmy Smith, as arranged by Lalo Schiffrin. This version was used to accompany the titles and credits for the UK BBC 2 The Money Programme, a finance and current affairs television magazine program. It was also used to introduce the BBC'S coverage of The Budget in 1987.

Prequel

[edit]As Alan Ladd had died before the film was released,[25] he was unavailable when the film's success suggested an audience for a prequel.

Nevada Smith was filmed and released two years later, with Steve McQueen as Smith.

In popular culture

[edit]Mad magazine lampooned the film in issue #92 with The Carpetsweepers.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The fruitful labours of Levine". Sunday Times. London, England. 11 Oct 1964. p. 29 – via The Sunday Times Digital Archive.

- ^ a b c Box Office Information for The Carpetbaggers. IMDb via Internet Archive. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. (1 January 2006). Literature Suppressed on Sexual Grounds. Infobase Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8160-7149-4.

- ^ McKenna, A.T. (2016). Showman of the Screen: Joseph E. Levine and His Revolutions in Film Promotion. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 103–7.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (June 30, 1962). "Columbia Pictures Will Endow Circle in Square Acting Grants". New York Times. p. 11. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Weiler, A.H. (November 30, 1962). "Miss Taylor and Richard Burton Are Sought for Roles in 'V.I.P.'s'". New York Times. p. 25. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (Mar 27, 1963). "Diane Baker Is Seeking Role in 'Lilith' Movie". Chicago Tribune. p. b2.

- ^ Weiler, A.H. (May 27, 1963). "'Carpetbaggers' Signs Alan Ladd: Actor to Play Nevada Smith In Film Version of Novel". New York Times. p. 25. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (July 23, 1963). "Looking at Hollywood: Bob Cummings Plays Baby-Faced Villain". Chicago Tribune. p. a1.

- ^ "Filmland Events: Alan Ladd Definite for 'Carpetbaggers'". Los Angeles Times. May 3, 1963. p. C10.

- ^ Morehouse, Ward (Aug 25, 1963). "Carroll Baker Explains Mood to Do Movie Scene in the Nude". Los Angeles Times. p. e6.

- ^ a b "HOLLYWOOD CANDOR; Carroll Baker Defends Her Nudity in Films". The New York Times. 14 June 1964. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ "The Carpetbaggers – Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ Box Office Information for The Carpetbaggers. The Numbers. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (29 December 2024). "Movie Star Cold Streaks: George Peppard". Filmink. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (July 2, 1964). "Screen: 'The Carpetbaggers' Opens". The New York Times. 24.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Carpetbaggers". Variety. April 15, 1964. 6.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 5, 1964). "'Carpetbaggers' in Bad Taste as Film". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 13.

- ^ Coe, Richard L. (June 13, 1964). "Carpetbaggers Safe on Base". The Washington Post. C34.

- ^ a b McNally, Karen (16 December 2010). Billy Wilder, Movie-Maker: Critical Essays on the Films. McFarland. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7864-8520-8.

- ^ "Most Popular Film Star". The Times. London. 31 December 1965. p. 13 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Lee; Worrall, Dave (29 November 2011). Cinema Sex Sirens. Omnibus Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-85712-725-9.

- ^ "The Carpetbaggers". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 31 (370): 159. November 1964.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (29 October 2024). "Movie Star Cold Streaks: Robert Cummings". Filmink. Retrieved 29 October 2024.

- ^ "Alan Ladd, Actor, Dies at 50; Appeared-in 150 Movie Roles: Became Famous for Part of Killer in 'This Gun for Hire' – Was Hero of 'Shane'". New York Times. January 30, 1964. p. 29. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Mad #92 January 1965". Doug Gilford's Mad Cover Site.

External links

[edit]- 1964 films

- 1964 drama films

- 1960s American films

- 1960s business films

- 1960s English-language films

- American aviation films

- American business films

- American drama films

- Embassy Pictures films

- English-language drama films

- Films à clef

- Films about film directors and producers

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Edward Dmytryk

- Films scored by Elmer Bernstein

- Films set in the 1920s

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Obscenity controversies in film