Adoration of the Magi (Mostaert)

| Adoration of the Magi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jan Mostaert |

| Year | circa 1520–1525 |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Dimensions | 51 cm × 36.5 cm (20 in × 14.4 in) |

| Location | Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam |

Adoration of the Magi is an oil on panel painting from the early 1520s by the Dutch Renaissance artist Jan Mostaert in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, where in 2020 it was on display in room 0.1.[1] The panel measures 51 cm × 36.5 cm (20 in × 14.4 in), and the painted surface a little less at 48.5 cm × 34 cm.[2] It is often called the Mostaert Amsterdam Adoration in art history, to distinguish it from the multitude of other paintings of the Adoration of the Magi.

Based on the Gospel of Matthew 2:1–12, Mary sits with her child in the ruins of an elaborate palace to receive the gifts of the three Biblical Magi, whose retinues are seen in the background, with a fantasy landscape.[1] The Christ child peers into Melchior's goblet of incense, which is inscribed "AVE MARIA" ("Hail Mary") around the rim. To the left, Saint Joseph stands watching and talking with a well-dressed figure behind the main group, and the heads of the traditional ox and ass can be seen. Smaller scenes shown decorating the ruined architecture include three scenes from the Old Testament,[3] and one from Christian legend.[4]

Melchior appears to be a portrait of the unknown person who commissioned the painting, and the older Caspar may be another portrait. The relatively small size of the panel and intimacy of the central group suggest a painting commissioned for a private house rather than a donation to a church or other public setting.[3]

Iconography

[edit]Many aspects of the iconography and composition of the painting are very similar to other Netherlandish depictions of this very popular subject from around this time, but some details are unusual.[5]

The Magi represent both the "three ages of man" and the three continents known to the medieval world. Melchior is traditionally shown as middle-aged and represents Asia; he is often specified as Persian. Most often it is Caspar, representing old age and Europe, whose moment of presentation of his gold is shown, but here presumably the donor's age suited a Melchior better. As usual, Balthazar, representing youth and Africa, is waiting his turn.[6]

Compositions showing the main figures at half-length, across the front of the image space, were an innovation of Hugo van der Goes late in the 15th century; two versions survive in early copies. They allow a closer and more intimate concentration on the main figures. Mostaert does not quite do this, and his vertical image format allows plenty of space above for the ruins, landscape, and retinues. However, he uses a smaller version of the table or ledge at the front centre.[7]

The stable of the account in the Gospel of Luke had often evolved into a ruined palace in paintings of the Nativity and the subsequent scenes. This was held to represent the palace of King David, who was also born in Bethlehem, and also symbolized the dilapidated state of the Old Covenant.[8] The two poorly dressed men in the mid-ground above Melchior's head probably represent the shepherds arriving at the scene, as do the similar figures in Jan Gossaert's Adoration of the Kings (National Gallery).[9] Both paintings show the ox and ass, but not prominently; they had only become usual in depictions of the Adoration of the Magi in the previous century.[10]

The costumes are mostly exotic versions of "modern" styles, and Mary's unusually rich dress has a "fashionable neckline", not to mention pearls hanging from the sleeve.[3] The Magi dress richly, but without the extravagant exoticism found in many depictions by contemporary Antwerp Mannerists.[11] Melchior wears a travelling cloak with a fashionable Spanish-style hood.[3]

Small scenes

[edit]

It is common in Early Netherlandish painting to have small religious scenes shown as sculpted reliefs in the background, to increase the depth of religious reference. But the choices of the four small scenes shown on the pillar and architrave just behind the main group, and above Mary and Jesus, are unusual in painting. On the architrave, with a red background, the left side has been identified as starting with the obscure and uncommon scene from 2 Samuel 23:15–18 of King David, when Bethlehem was held by the Philistines, refusing to drink the water that three men had drawn from a well at great risk to themselves:[3]

15 David longed for water and said, "Oh, that someone would get me a drink of water from the well near the gate of Bethlehem!" 16 So the three mighty warriors broke through the Philistine lines, drew water from the well near the gate of Bethlehem and carried it back to David. But he refused to drink it; instead, he poured it out before the Lord. 17 "Far be it from me, Lord, to do this!" he said. "Is it not the blood of men who went at the risk of their lives?" And David would not drink it. (NIV)[12]

This scene had sometimes been used in art as a typological prefiguration of the Adoration of the Magi, apparently based on the basic similarity of a visual composition of three men offering something to a royal figure regarded as an ancestor of Jesus, rather than any theological relationship. For example, they appear in an altarpiece panel by Conrad Witz, and are carved in the frame of Michael Pacher's St. Wolfgang Altarpiece (St. Wolfgang im Salzkammergut, Austria, 1471–81).[13]

To the right of that, along the beam, is a horizontal version of the much better-known scene of the Tree of Jesse, from Isaiah 11:1–12, which viewers of the period would easily have recognised. In the medieval Christian view, this illustrated the genealogy of Jesus.[14]

On the pillar there is the Tiburtine Sibyl showing Augustus a vision high above them, a well-known Christian legend.[3] In the versions known to the later Middle Ages the Emperor Augustus asked the sibyl whether he should be worshipped as a god, as the Roman Senate had ordered. She replied by showing him a vision of a young woman with a baby boy, high in the sky, while a voice from the heavens said "This is the virgin who shall conceive the saviour of the world". The episode was regarded as a prefiguration of the Magi's visit, and for example is paired with an Adoration of the Magi on the two side-wings of Rogier van der Weyden's Bladelin Altarpiece (1460), now Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.[15]

Below this on the pillar is the dream of the butler (or "cupbearer") from the Old Testament story of Joseph in Genesis 40: 9–15. He sits in the stocks, to represent his imprisoned state, carries Pharaoh's cup, but "oddly" wears a crown himself.[16]

9 So the chief cupbearer told Joseph his dream. He said to him, "In my dream I saw a vine in front of me, 10 and on the vine were three branches. As soon as it budded, it blossomed, and its clusters ripened into grapes. 11 Pharaoh's cup was in my hand, and I took the grapes, squeezed them into Pharaoh's cup and put the cup in his hand."

12 "This is what it means", Joseph said to him. "The three branches are three days. 13 Within three days Pharaoh will lift up your head and restore you to your position, and you will put Pharaoh's cup in his hand, just as you used to do when you were his cupbearer".[17]

A typical medieval interpretation of the prefiguring relationship with the birth of Christ was that "the cup bearer symbolized humanity captive in sin, the vine symbolized Christ who would redeem mankind, and the grape juice prefigured the blood of Christ."[18]

All these scenes are found in various versions of the Speculum humanae salvationis, an illustrated handbook of typological pairings, mostly between the Old and New Testaments, which was highly popular in illuminated manuscript, blockbook, and printed forms from the 14th to the early 16th centuries. Mostaert seems to have used a blockbook edition from some fifty years earlier as the basis of his compositions.[19]

Both a scene of Augustus and the Sibyl (in the background at left), and a vine relief pattern on a red background on a pillar appear in Mostaert's Portrait of the Knight Abel van Coustler, probably of a similar date,[20] and a very similar scene and background building are used in a female portrait in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.[21] A small painting of Joseph explaining the dreams of the Baker and Butler, c, 1500, in the Mauritshuis is tentatively attributed to Mostaert. Each dream is illustrated on the wall above the dreamer.[22] A Tree of Jesse, hung near the Mostaert Adoration, has a complicated and disputed attribution, according to some scholars involving Mostaert, as well as Geertgen tot Sint Jans, who died in Haarlem in 1495, or his workshop or pupils.[23]

-

Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl

-

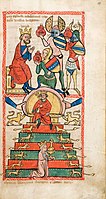

The butler's dream paired with the Nativity in a manuscript Speculum humanae salvationis, Rhineland, 1360s.[24]

-

The "three mighty warriors" offer King David water, in the same manuscript

-

Mostaert's Portrait of the Knight Abel van Coustler

-

Mostaert (?), Joseph explaining the dreams of the Baker and Butler, c, 1500, Mauritshuis

-

Tree of Jesse, Rijksmuseum, possibly involving Mostaert, as well as Geertgen tot Sint Jans or his workshop or pupils

Technical

[edit]The painting is on a single oak panel, 1.3 cm thick. It is in good condition, and was restored in 2007. Infrared reflectography shows a detailed underdrawing, to which various minor changes have been made during painting.[3]

Provenance

[edit]The painting is documented as far back as the estate inventory of Anna van Renesse, Lady of Assendelft (1622–1667), at Assumburgh Castle near Heemskerk.[25] This painting was purchased in 1879 from the heirs of the original owners through the mediation of Cornelis François Roos, the son of Cornelis Sebille Roos, and has been included in all Highlights of the Rijksmuseum catalogues since.[3]

-

Jesus examining Melchior's gift

-

The left side: ox and ass, Balthazar, Saint Joseph, shepherds (?), Melchior

-

Right side: Caspar, retinues and landscape

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Catalogue entry on museum website

- ^ Rijksmuseum, at "object data" tab

- ^ a b c d e f g h Filedt Kok

- ^ Hall, 282

- ^ Schiller, 110–114

- ^ Schiller, 100–114; Hall, 6; Filedt Kok

- ^ Ainsworth, 368-370; Schiller, 114; Filedt Kok

- ^ Schiller, 81–82; Hall, 220, 269; Filedt Kok

- ^ Gossaert, 14

- ^ Schiller, 112

- ^ Compare Gossaert, 14 for example

- ^ Text from www.biblegateway.com

- ^ Schiller, 110 (the only examples her exhaustive account mentions)

- ^ Schiller, 12–22; Filedt Kok

- ^ Schiller, 82; Hall, 282; Murrays, 41. The precise details of the legend vary.

- ^ Filedt Kok; Rijksmuseum, at "object data" tab

- ^ NIV from www.biblegateway.com

- ^ Wilsons, 156

- ^ Filedt Kok, note 14; Wilsons, 148, 156–159; British Library, Harley MS 2838, 1485–1509, see ff 6v, 10v, 11r, 12r

- ^ RKD page, # 19726

- ^ Berlin portrait

- ^ Mauritshuis

- ^ Snyder, throughout; Rijksmuseum online catalogue page (by Filedt Kok). In 2020 it is given to "Geertgen tot Sint Jans (circle of)" by the museum.

- ^ Not the version Filedt Kok refers to, nor apparently with the same pairings

- ^ Painting's record on museum website

- ^ Campbell, 32

References

[edit]- Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn et al., From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. ISBN 0-8709-9870-6, google books

- Filedt Kok, Jan Piet, "Jan Jansz Mostaert, The Adoration of the Magi, Haarlem, c. 1520 – c. 1525", in J.P. Filedt Kok (ed.), Early Netherlandish Paintings, online coll. cat. Amsterdam 2010 (accessed 18 December 2020).

- "Gossaert": Jean Gossart, The Adoration of the Kings, Lorne Campbell, from The Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings with French Paintings before 1600, London 2011; published online 2011 Archived 2021-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Murray, Peter and Linda, revised Tom Devonshire Jones, The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art & Architecture, 2014, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199695102, 0199695105

- Schiller, Gertud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0853312702

- Snyder, James. “The Early Haarlem School of Painting, Part III: The Problem of Geertgen Tot Sint Jans and Jan Mostaert.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 53, no. 4, 1971, pp. 445–458. JSTOR

- Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson (1984). A Medieval Mirror. Berkeley: University of California Press. online edition Includes many illustrations, including a full set of woodcut pictures with notes in Chapter 6.

![The butler's dream paired with the Nativity in a manuscript Speculum humanae salvationis, Rhineland, 1360s.[24]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/43/Speculum_Darmstadt_2505_16v.jpg/107px-Speculum_Darmstadt_2505_16v.jpg)

![Jan Gossaert, The Adoration of the Kings, National Gallery, 1506–1516.[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Jan_Gossaert_001.jpg/182px-Jan_Gossaert_001.jpg)