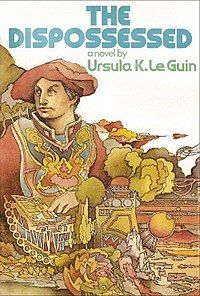

The Dispossessed

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Ursula K. Le Guin |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | The Ekumen Universe |

| Genre | Science Fiction |

| Publisher | Harper & Row |

Publication date | 1974 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 341 pp (First Edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-060-12563-2 (First edition, hardcover) Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia is a 1974 utopian science fiction novel by Ursula K. Le Guin, set in the same fictional universe as that of The Left Hand of Darkness (the Ekumen universe). The book won both the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award in 1975, and is notable for achieving a degree of literary recognition unusual for science fiction works.

Plot summary

Template:Spoiler The story takes place on the fictional planet Urras and its moon Anarres (since Anarres is massive enough to hold an atmosphere, this is often described as a double planet system). In order to forestall an anarcho-syndical workers' rebellion, the major Urrasti states gave Anarres and a guarantee of non-interference to the revolutionaries, approximately 200 years before the events of The Dispossessed.

The protagonist Shevek is a physicist attempting to develop a General Temporal Theory. The physics of the book describes time as having a much deeper, more complex structure than we understand it. It incorporates not only mathematics and physics, but also philosophy and ethics. The meaning of the theories in the book weaves nicely into the plot, not only describing abstract physical concepts, but the ups and downs of the characters lives, and the transformation of the Anarresti society. An oft-quoted saying in the book is "True journey is return."

Anarres is in theory a society without government or coercive authoritarian institutions. Yet Shevek begins to come up against very real walls as his ideas begin to deviate from the opinions of his countrymen. Gradually he develops an understanding that the revolution which brought his world into being is becoming stagnant, and power structures begin to exist where there were none before. He therefore embarks on the risky journey to the original planet, Urras, seeking to open dialog between the worlds and to spread his theories freely outside of Anarres. The novel details his struggles on both Urras and his homeworld of Anarres.

The book also explores the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: on the anarchist planet the use of the possessive case is strongly discouraged. An example is given where Shevek's daughter, meeting him for the first time, tells him "You can share the handkerchief I use." (Le Guin 69), rather than "you may borrow my handkerchief". The idea is that the handkerchief is not owned by the girl, merely carried by her. The language spoken in Anarres, Pravic, is a constructed language that reflects many aspects of the philosophical foundations of utopian anarchism.

The Dispossessed is considered by some libertarian socialists to be a good description of the mechanisms that would be developed by an anarchist society, but also of the dangers of centralization and bureaucracy that easily take over such society without the continuation of revolutionary ideology. Part of its power is that it gives us a spectrum of fairly well-developed characters, who illustrate many types of personalities, all educated in an environment that measures a person not by what he owns, but by what he can do, and how he relates to other human beings. Probably the best example of this is the character of Takver, the hero's partner, who exemplifies many virtues: loyalty, love of life and living things, perseverance, and desire for a true partnership with another person.

The work is sometimes said to represent one of the few modern revivals of the utopian genre, there are certainly many characteristics of a utopian novel found in this book, Shevek is an outsider in Urras, there are no 'Mrs Browns' in that all of the characters are shown to have a certain spirituality or intelligence, there are no nondescript characters. It is also true to say that there are aspects of Anarres that are utopian, it is presented as a pure society, that adheres to its own theories and ideals, which is made much more stark by the juxtaposition with Urras. However, Anarres is not presented as a perfect society, and there are aspects of realism that detract from the utopian elements of the novel. There is mention of hardship due to lack of resources, albeit due to the profiteering world of Urras, the importance lies in the fact Anarres is not safe from hardship, therefore it is not a perfect society. Le Guin shows that there is no such thing possible. It is notable that one of the major themes of the work is the ambiguity of different notions of utopia.

Quotations

...if it is the future you seek, then I tell you that you must come to it with empty hands. You must come to it alone, and naked, as the child comes into the world, into his future, without any past, without any property, wholly dependent on other people for his life. You cannot take what you have not given, and you must give yourself. You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.

— Shevek, page 241

For we each of us deserve everything, every luxury that was piled in the tombs of the dead kings, and we each of us deserve nothing, not a mouthful of bread in hunger. Have we not eaten while another starved? Will you punish us for that? Will you reward us for the virtue of starving while others ate? No man earns punishment, no man earns reward. Free your mind of the idea of deserving, the idea of earning, and you will begin to be able to think.

— Odo, page 288

A child free from the guilt of ownership and the burden of economic competition will grow up with the will to do what needs doing and the capacity for joy in doing it. It is useless work that darkens the heart. The delight of the nursing mother, of the scholar, of the successful hunter, of the good cook, of the skilful maker, of anyone doing needed work and doing it well, — this durable joy is perhaps the deepest source of human affection and of sociality as a whole.

— Odo, page 207

With the myth of the State out of the way, the real mutuality and reciprocity of society and individual became clear. Sacrifice might be demanded of the individual, but never compromise: for, though only the society could give security and stability, only the individual, the person, had the power of moral choice — the power of change, the essential function of life. The Odonian society was conceived as a permanent revolution, and revolution begins in the thinking mind.

— Page 276

You see, what we're after is to remind ourselves that we didn't come to Anarres for safety, but for freedom. If we must all agree, all work together, we're no better than a machine. If an individual can't work in solidarity with his fellows, it's his duty to work alone. His duty and his right. We have been denying people that right. We've been saying, more and more often, you must work with the others, you must accept the rule of the majority. But any rule is tyranny. The duty of the individual is to accept no rule, to be the initiator of his own acts, to be responsible. Only if he does so will the society live, and change, and adapt, and survive. We are not subjects of a State founded upon law, but members of a society formed upon revolution. Revolution is our obligation: our hope of evolution. The Revolution is in the individual spirit, or it is nowhere. It is for all, or it is nothing. If it is seen as having any end, it will never truly begin. We can't stop here. We must go on. We must take the risks.

— Shevek, page 296

In the afternoon, when he cautiously looked outside, he saw an armored car stationed across the street and two others slewed across the street at the crossing. That explained the shouts he had been hearing: it would be soldiers giving orders to each other.

Atro had once explained to him how this was managed, how the sergeants could give the privates orders, how the lieutenants could give the privates and the sergeants orders, how the captains... and so on and so on up to the generals, who could give everyone else orders and need take them from none, except the commander in chief. Shevek had listened with incredulous disgust. “You call that organization?” he had inquired. “You even call it discipline? But it is neither. It is a coercive mechanism of extraordinary inefficiency — a kind of seventh-millennium steam engine! With such a rigid and fragile structure what could be done that was worth doing?” This had given Atro a chance to argue the worth of warfare as the breeder of courage and manliness and weeder-out of the unfit, but the very line of his argument had forced him to concede the effectiveness of guerrillas, organized from below, self-disciplined. “But that only works when the people think they're fighting for something of their own — you know, their homes, or some notion or other,” the old man had said. Shevek had dropped the argument. He now continued it, in the darkening basement among the stacked crates of unlabeled chemicals. He explained to Atro that he now understood why the Army was organized as it was. It was indeed quite necessary. No rational form of organization would serve the purpose. He simply had not understood that the purpose was to enable men with machine guns to kill unarmed men and women easily and in great quantities when told to do so. Only he still could not see where courage, or manliness, or fitness entered in.

See also

External links

- The Dispossessed title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Study Guide for Ursula LeGuin: The Dispossessed (1974) ISBN 0-06-105488-7

- Review of The Dispossessed