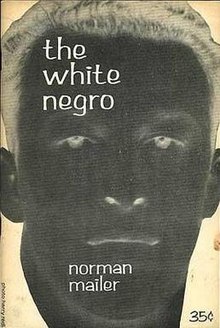

The White Negro

(publ. City Lights)

"The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster" is a 9,000 word essay by Norman Mailer that recorded a number of young white people between the 1920s and 1950s who liked jazz and swing music, and who were so dis-enthralled with what they saw as a conformist culture, that they adopted black culture as their own.[1][2] The essay was first published in the Summer 1957 issue of Dissent,[3] before being published separately by City Lights.[4] It later appeared in Advertisements for Myself in 1959.

Essay summary

Section 1

Mailer begins the essay by stating:

- "Probably, we will never be able to determine the psychic havoc of the concentration camps and the atom bomb upon the unconscious mind of almost everyone alive in these years."

Using the context of a post-WWII society, Mailer asserts that the atrocities of the war have forced humanity to recognize the possibility of a "death by 'deus ex machina' in a gas chamber or in a radioactive city." He feels as if this reality has stifled dissent and that we live in years of "conformity and depression". He observes that "a stench of fear has come out of every pore of American life, and we suffer from a collective failure of nerve," asserting that acts of courage have been isolated.

Section 2

After his initial exposition, Mailer begins the second section of "The White Negro" by observing that:

- "It is on this bleak scene that a phenomenon has appeared: the American existentialist—the hipster (339)"

The "hipster" knows that contemporary society must live under the threat of "instant death by atomic war, relatively quick death by the State as l’univers concentrationnaire, or with a slow death by conformity with every creative and rebellious instinct stifled (339)." This realization has led the hipster to accept that:

- "the only life-giving answer is to accept the terms of death, to live with death as immediate danger, to divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots, to set out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self (339)."

The lifestyle of the hipster, the American-existentialist, is one that operates in "the enormous present"; he must "be with it or doomed not to swing." There is a distinction between being Hip and being Square, one that draws a parallel to rebellion and conformity.

Mailer goes on to explain that "the source of Hip is the Negro for he has been living on the margin between totalitarianism and democracy for two centuries (340)." He attributes the proliferation of the hip mentality to the "knifelike entrance" of jazz into culture, explaining that the post-war generation shared a "collective disbelief in the words of men who had too much money and controlled too many things (340)." Mailer suggests that the thought processes of this generation can be traced to D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and Wilhelm Reich, claiming that the philosophy of Ernest Hemingway is also applicable to the reality of the hipsters.

Returning to the role of African-American culture on this phenomenon, Mailer explains that hipsters "absorbed the existentialist synapses of the Negro, and for practical purposes could be considered a white Negro, (341)" giving the essay its title. Smoking marijuana was the "wedding ring" of this relationship and language was "the child." The "language of Hip … gave expression to abstract states of feeling which all could share, at least all those who were Hip (340)." The Negro, unable to "saunter down a street with any real certainty that violence will not visit him," has "kept for his survival the art of the primitive … relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body (341)." So, the hipster, the white Negro, uses the "black man’s code" to live their life.

Their existentialism allows them to "feel" themselves. According to Mailer, this existentialism requires a sort of religion; it gives them purpose. He refers to them as mystics who have "chosen to live with death (342)." Death is their "logic"; living with it is their religion. They live is search for their next orgasm, good or bad.

This outline of the hipster and the Hip mentality is the primary topic of section 2 of "The White Negro".

Section 3

Mailer uses the 3rd section of "The White Negro" to discuss and dissect the psychology of the hipster. He appropriately starts the section by saying:

- "It may be fruitful to consider the hipster a philosophical psychopath, a man interested not only in the dangerous imperatives of his psychopathy but in codifying, at least for himself, the suppositions on which his inner universe is constructed (343)."

In what seems to be a paradox Mailer explains that the hipster "is a psychopath, and yet not a psychopath but the negation of the psychopath (343)." He explains this understanding by pointing out that the hipster, the philosophical psychopath, is self-aware, a trait that the "unreasoning drive" of the psychopath does not possess. To Mailer "Hip is the sophistication of the wise primitive in a giant jungle"; the hipster’s "intense view of existence matches their experience and their desire to rebel (343)."

He goes on to explain the polarity between the psychopath and the psychotic; the "psychotic is legally insane, the psychopath is not (344)." Mailer draws from Sheldon Glueck (& his wife Eleanor) along with Robert M. Lindner in observing that the psychopath is anti-social only interested in satisfying himself (344). He then distances himself from Lindler, stating that Lindler:

- "was not ready to project himself into the essential sympathy-which is that the psychopath may indeed be the perverted and dangerous front-runner of a new kind of personality which could become the central expression of human nature before the twentieth century is over (345)."

Mailer’s reasoning for this prediction is that the psychopath "is better adapted to dominate those mutually contradictory inhibitions upon violence and love which civilization has exacted of us (345)," referencing one his earlier observations that, in contemporary America, "sex is sin and yet sex is paradise (343)." This new personality is a reaction against psychoanalysis and conformity; one that is free from the inhibitions of the "inefficient and often antiquated nervous circuits of the past (345)." He explains that old "circuits" limit human potentials that "might be exciting for our individual growth."

Elaborating on the reaction against psychoanalysis, Mailer states that in "a crisis of accelerated historical tempo and deteriorated values, neurosis tends to be replaced by psychopathy, and the success of psychoanalysis diminishes (345-46)." The analysts are becoming less complex and less experienced compared to their patients, turning psychoanalysis into nothing more than "psychic blood-letting (346)." Psychopaths are difficult to psychoanalyze because their nature leads them to an attempt at living the "infantile fantasy," something Mailer claims may have "a certain instinctive wisdom." The psychopath wants to "grow up a second time" and knows that "to express a forbidden impulse actively is far more beneficial to him than merely" telling a doctor that he wants to (346).

Returning to the source of much of his thought, Mailer observes that the Negro is most familiar with this type of existence; he explores what the Square condemns. Not being privileged with conventional gratification, the Negro has "discovered and elaborated the morality of the bottom (348)." Mailer concludes this section by explaining that the language of Hip is special and "cannot really be taught (348)."

Section 4

One of the definitive characteristics of the hipster is their language, adopted in large part from the African-American vernacular. Their language is a language with much energy; without this energy the same message would not be delivered. Their vocabulary is semantically so flexible that a single word, such as "dig," can mean hundreds of things depending upon everything from context to tone and rhythm. Mailer speaks of what he calls the Mecca, the apocalyptic orgasm, in which the hipster experiences. He says:

- "If everyone in the civilized world is at least in some small degree cripple, the hipster lives with the knowledge of how he is sexually crippled and where he is sexually alive, and the faces of experience which life presents to him each day are engaged, dismissed or avoided as his need directs and his lifemanship makes possible."

According to Mailer, being so disenfranchised by mainstream American society, the African-American views everyday life in the terms of war, which the hipster adopts as his model for the rejection of conformity.

Section 5

Mailer begins section five of "The White Negro" by stating that a new philosophy, in this case Hip, must have a new language, though the language does not necessarily show its philosophy. He then asks what is "unique in the life-view of Hip," to which he says:

- "The answer would be in the psychopathic element of Hip which has almost no interest in viewing human nature, or better, in judging human nature, from a set of standards conceived a priori to the experience, standards inherited from the past (353)."

Hip, being an existential philosophy of the enormous present, rejects much of the paradigm of former systems; it focuses "on complexity rather than simplicity." In the Hip life-view "each man is glimpsed as a collection of possibilities." According to Mailer, context dominates man, "because his character is less significant than the context in which he must function (353)." Truth is "what one feels at each instant in the perpetual climax of the present (354)."

Mailer explains that,

- "Hip morality is to do what one feels whenever and wherever it is possible, and – this is how the war of the Hip and the Square begins- to be engaged in one primal battle: to open the limits of the possible for oneself, for oneself alone, because that is one's need. Yet in widening the arena of the possible, one widens it reciprocally for others as well, so that the nihilistic fulfillment of each man’s desire contains its antithesis of human co-operation (354)."

He goes on to state that "Hip ethic is immoderation, childlike in its adoration of the present," and that it "proposes as its final tendency that every social restraint and category be removed (354)."

Mailer then explains that the main woe of the mid-twentieth century is that "faith in man has been lost," something that has allowed for the rise of authoritarian powers to "restrain us from ourselves." Hip, which Mailer suggests "would return us to ourselves," believes that "individual acts of violence are always to be preferred to the collective violence of the State (355)."

Moving into speculation about the future of the hipster, Mailer admits that it is "not very possible to speculate with sharp focus." That being said, he moves back into the role of the Negro, explaining that "the organic growth of Hip depends on whether the Negro emerges as a dominating force in American life (356)." The Negro is more familiar with the dark side of life than the white, which could give him a "potential superiority". This superiority is "so feared that the fear itself has become the underground drama of domestic politics"; it is the traditionally conservative fear of "unforeseeable consequences."

Mailer then suggests that:

- "With this possible emergence of the Negro, Hip may erupt as a physically armed rebellion whose sexual impetus may rebound against the antisexual foundation of every organized power in America, and bring into the air such animosities, antipathies, and new conflicts of interest that the mean empty hypocrisies of mass conformity will no longer work (356)."

He goes on to explain that when the Negro does win his equality much will depend on the response of liberals, pointing out the dichotomy between a peaceful transition and an anarchical political system. He concludes by stating that "given such hatred, [society] must either vent itself nihilistically or become turned into the cold murderous liquidations of the totalitarian state (357).

Section 6

In the last section of Mailer's essay, he suggest the Negro may hold knowledge based on his own position in life and his experiences and a more comprehensive way of thinking may be worthy, even though it may be frightening.

Interpretation/analysis

The so-called white Negroes adopted black clothing styles, black jive language, and black music. They mainly associated with black people, distancing themselves from white society. One of the early figures in the white negro phenomenon was jazz musician Mezz Mezzrow, an American Jew born in 1899 who had declared himself a "voluntary Negro" by the 1920s.[5] This movement influenced the hipsters of the 1940s and the beats of the 1950s.

Although the essay considers a subcultural phenomenon, it represents a localized synthesis of Marx and Freud, and thus presages the New Left movement and the birth of the counterculture in the United States. Probably the most prominent academic exponent of the New Left in the US was Herbert Marcuse. The essay is also very prescient because it anticipates the pejorative use of the word wigger in contemporary society to refer to white people who emulate the manner of speech, the fashion styles, or other aspects of the expressive culture of African Americans.

Resources

- The White Negro. Mailer's text at Dissent magazine. Retrieved: 2010-11-26.

- Grundmann, Roy (2003). Andy Warhol's Blow Job. Culture and the moving image. Temple University Press. pp. 169–177. ISBN 1-56639-972-6.

- Mailer, Norman. "The White Negro." Advertisements for Myself. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1966. 337-58. Print.

References

- ^ Norman Mailer's Hipster Theory: Whatever Became of the White Negro?, by Christian Lorentzen. 2007-12-31. Retrieved: 2010-10-25.

- ^ The White Negro. Mailer's text at Dissent magazine. Retrieved:2012-11-26.

- ^ Sorin, Gerald (2005). Irving Howe: A Life of Passionate Dissent. NYU Press. pp. 144–145, 330. ISBN 0-8147-4020-0.

- ^ AbeBooks.co.uk

- ^ The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz p. 146 By Leonard Feather, Ira Gitler. Retrieved:2010-10-25.