The switch in time that saved nine

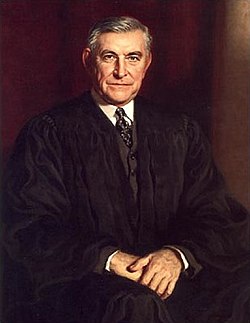

In U.S. Supreme Court history, "The switch in time that saved nine" is the phrase—originally a quip by humorist Cal Tinney[1]—about what was perceived in 1937 as the sudden jurisprudential shift by associate justice Owen Roberts in the 1937 case West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish.[2] Conventional historical accounts portrayed the Court's majority opinion as a strategic political move to protect the Court's integrity and independence from President Franklin Roosevelt's court-reform bill (also known as the "court-packing plan"), but later historical evidence gives weight to Roberts' decision being made immediately after oral arguments, much earlier than the bill's introduction.

The term itself is a reference to the aphorism "a stitch in time saves nine", meaning that preventive maintenance before something breaks is less work than fixing that thing after it breaks.[3]

Conventional account

[edit]Through the 1935–36 terms, Roberts had been the deciding vote in several 5–4 decisions invalidating New Deal legislation, casting his vote with the "conservative" bloc of the bench, the so-called "Four Horsemen".[4] This "conservative" wing of the bench is viewed to have been in opposition to the "liberal Three Musketeers".[5] Justice Roberts and Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, the remaining two justices, were the center swing votes.[6]

The "switch" came in the case West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, when the Court announced its opinion in March 1937.[2] Roberts switched sides and joined Chief Justice Hughes, and Justices Louis Brandeis, Benjamin N. Cardozo, and Harlan Fiske Stone in upholding a Washington minimum wage law. The decision was handed down less than two months after President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced his court-reform bill. Conventional history has painted Roberts's vote as a strategic, politically motivated shift to "save nine", meaning it defused Roosevelt's drive to increase the number of justices on the Supreme Court beyond nine.[7] At the time, much of the public thought Roberts was trying to defeat Roosevelt's proposed legislation, but the historical record also lends weight to assertions that Roberts's decision was made much earlier, before the bill's introduction.[8]

The ruling marked the end of the Lochner era, a forty-year period in which the Supreme Court often struck down legislation that regulated business activity.[9]

Historical view

[edit]Popular as well as some scholarly understanding of the Hughes Court has typically cast it as divided between a conservative and liberal faction, with two critical swing votes. The conservative Justices Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter were known as "The Four Horsemen". Opposed to them were the liberal Justices Louis Brandeis, Benjamin Cardozo and Harlan Fiske Stone, dubbed "The Three Musketeers". Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts were regarded as the swing votes on the court.[10] Recent scholarship has eschewed these labels since they suggest more legislative, as opposed to judicial, differences.[11] While it is true that many rulings of the 1930s Supreme Court were deeply divided, with four justices on each side and Justice Roberts as the typical swing vote, the ideological divide this represented was linked to a larger debate in U.S. jurisprudence regarding the role of the judiciary, the meaning of the Constitution, and the respective rights and prerogatives of the different branches of government in shaping the judicial outlook of the Court.

Roberts had voted to grant certiorari to hear the Parrish case before the election of 1936.[12] Oral arguments occurred on December 16 and 17, 1936, with counsel for Parrish specifically asking the court to reconsider its decision in Adkins v. Children's Hospital,[13] which had been the basis for striking down a New York minimum wage law in Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo[14] in the late spring of 1936.[15] In Tipaldo, the appellant had not challenged the Adkins precedent.[16][17] Having no "case or controversy" legs upon which to stand, Roberts and the rest of the majority deferred to the Adkins precedent, voting to strike the New York statute.[17] Justice Butler authored the opinion of the Court in the Tipaldo case. He and the rest of the majority, excluding Roberts, shortly thereafter found themselves in the minority on the Parrish case.

In the Parrish case, Roberts indicated his desire to overturn Adkins immediately after oral arguments on December 17, 1936.[15] The initial conference vote on December 19, 1936, was split 4–4; with this even division on the Court, the holding of the Washington Supreme Court, finding the minimum wage statute constitutional, would stand.[18] The eight voting justices anticipated Justice Stone—absent due to illness—would be the fifth vote necessary for a majority opinion affirming the constitutionality of the minimum wage law.[18] As Chief Justice Hughes desired a clear 5–4 affirmation of the Washington Supreme Court's judgment, rather than a 4–4 default affirmation, he convinced the other justices to wait until Stone's return before both deciding and announcing the case.[18]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced his court reform bill on February 5, 1937, the day of the first conference vote after Stone's February 1, 1937, return to the bench. Roosevelt later made his justifications for the bill to the public on March 9, 1937, during his ninth fireside chat. The Court's opinion in Parrish was not published until March 29, 1937, after Roosevelt's radio address. Chief Justice Hughes wrote in his autobiographical notes that Roosevelt's court reform proposal "had not the slightest effect on our [the court's] decision", but due to the delayed announcement of its decision the Court was characterized as retreating under fire.[8] Roosevelt also believed that because of the overwhelming support that had been shown for the New Deal in his re-election, Hughes was able to persuade Roberts to no longer base his votes on his own political beliefs and side with him during future votes on New Deal related policies.[19] In one of his notes from 1936, Hughes wrote that Roosevelt's re-election forced the court to depart from "its fortress in public opinion".[20]

The "switch", together with the retirement of Justice Van Devanter at the end of the 1937 spring term, is often viewed as having contributed to the demise of Roosevelt's court reform bill. The failure of the bill preserved the size of the U.S. Supreme Court at nine justices, as it had been since 1869 and remains to this day.

Roberts burned his legal and judicial papers,[21] so there is no significant collection of his manuscript papers as there is for most other modern Justices. However, in 1945, Roberts did provide Justice Felix Frankfurter with a memorandum detailing his own account of the events leading up to his vote in the Parrish case. In the memorandum, Roberts concluded that, "no action taken by the President in the interim [between the Tipaldo and Parrish cases] had any causal relation to my action in the Parrish case."[22]

From this, Justice Frankfurter called the charge against Roberts "false" and concluded:

It is one of the most ludicrous illustrations of the power of lazy repetition of uncritical talk that a judge with the character of Roberts should have attributed to him a change of judicial views out of deference to political considerations. ... Intellectual responsibility should, one would suppose, save a thoughtful man from the familiar trap of post hoc, ergo propter hoc.[22]

See also

[edit]- History of the Supreme Court of the United States

- Court-packing

- Swing justice, a colloquial term referring to the fifth justice likely to tip the court's majority one way or another

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Barrett, John Q. "Attribution Time: Cal Tinney's 1937 Quip, "A Switch in Time'll Save Nine,"". SSRN. Social Science Research Network. SSRN 3586608. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ a b 300 U.S. 379 (1937)

- ^ The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition Archived 2007-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Leuchtenburg 1995, p. 132-133.

- ^ White 2000, p. 81.

- ^ Leuchtenburg 1995, p. 133.

- ^ White 2000, p. 308.

- ^ a b McKenna 2002, p. 419.

- ^ Philips 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Jenson, Carol E. (1992). "New Deal". In Hall, Kermit L. (ed.). Oxford Companion to the United States Supreme Court. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kalman, Laura (2005). "AHR Forum: The Constitution, the Supreme Court, and the New Deal". American Historical Review. 110 (4). Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association. doi:10.1086/ahr.110.4.1052. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29.

- ^ McKenna 2002, p. 412–13.

- ^ 261 U.S. 525 (1923)

- ^ 298 U.S. 587 (1936)

- ^ a b McKenna 2002, p. 413.

- ^ Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587, 604-05 (1936) ("The petition for the writ sought review upon the ground that this case is distinguishable from that one [Adkins]. No application has been made for reconsideration of the constitutional question there decided. ... He is not entitled, and does not ask, to be heard upon the question whether the Adkins case should be overruled. He maintains that it [the New York minimum wage law] may be distinguished on the ground that the statutes are vitally dissimilar.").

- ^ a b Cushman 1998, p. 92–104.

- ^ a b c McKenna 2002, p. 414.

- ^ McKenna 2002, p. 422–23.

- ^ Devins, Neal (1996). "Government Lawyers and the New Deal". William & Mary Law School. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ Carter, Edward L.; Adams, Edward E. (August 15, 2012). "Justice Owen J. Roberts on 1937". The Green Bag.

- ^ a b Frankfurter, Felix (December 1955). "Mr. Justice Roberts". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Barrett, John Q. "Attribution Time: Cal Tinney's 1937 Quip, "A Switch in Time'll Save Nine,"". SSRN. Social Science Research Network. SSRN 3586608. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Cushman, Barry (1998). Rethinking the New Deal Court: The Structure of a Constitutional Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511532-1.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (1995). The Supreme Court Reborn: The Constitutional Revolution in the Age of Roosevelt. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511131-6.

- McKenna, Marian C. (2002). Franklin Roosevelt and the Great Constitutional War: The Court-packing Crisis of 1937. New York, NY: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-2154-7.

- Philips, Michael J. (2001). The Lochner Court, Myth and Reality: Substantive Due Process from the 1890s to the 1930s. Westport, Conn: Praeger, Greenwood. p. 10. ISBN 0-275-96930-4.

- White, G. Edward (2000). The Constitution and the New Deal. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00831-1.