Thomas Hart Benton (painter)

Thomas Hart Benton | |

|---|---|

Benton in 1935 | |

| Born | April 15, 1889 |

| Died | January 19, 1975 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | "America Today" (1930-31), "Indiana Murals" (1933), "Social History of Missouri" (1936), "Persephone" (1938-39)[3] |

| Movement | Regionalism, Social Realism, American modernism, American realism, Synchromism |

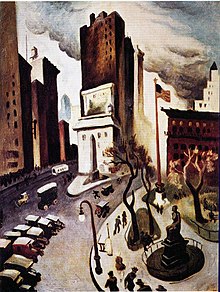

Thomas Hart Benton (April 15, 1889 – January 19, 1975) was an American painter and muralist. Along with Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, he was at the forefront of the Regionalist art movement. His fluid, sculpted figures in his paintings showed everyday people in scenes of life in the United States. Though his work is strongly associated with the Midwestern United States, he studied in Paris, lived in New York City for more than 20 years and painted scores of works there, summered for 50 years on Martha's Vineyard off the New England coast, and also painted scenes of the American South and West.

Early life and education

Benton was born in Neosho, Missouri, into an influential family of politicians. He had two younger sisters, Mary and Mildred, and a younger brother, Nathaniel.[4] His mother was Elizabeth Wise Benton and his father, Colonel Maecenas Benton, was a lawyer and four times elected as U.S. congressman. Known as the "little giant of the Ozarks", Maecenas named his son after his own great-uncle [5] Thomas Hart Benton, one of the first two United States Senators elected from Missouri.[4] Given his father's political career, Benton spent his childhood shuttling between Washington, D.C. and Missouri. His father sent him to Western Military Academy in 1905-06, hoping to shape him for a political career. Growing up in two different cultures, Benton rebelled against his father's plans. He wanted to develop his interest in art, which his mother supported. As a teenager, he worked as a cartoonist for the Joplin American newspaper, in Joplin, Missouri.[6]

With his mother's encouragement, in 1907 Benton enrolled at the The School of The Art Institute of Chicago. Two years later, he moved to Paris in 1909 to continue his art education at the Académie Julian.[7] His mother supported him financially and emotionally to work at art until he married in his early 30s. His sister Mildred said, "My mother was a great power in his growing up."[4] In Paris, Benton met other North American artists, such as the Mexican Diego Rivera and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, an advocate of Synchromism. Influenced by the latter, Benton subsequently adopted a Synchromist style.[8]

Early career and World War I

After studying in Europe, Benton moved to New York City in 1912 and resumed painting. During World War I, he served in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at Norfolk, Virginia. His war-related work had an enduring effect on his style. He was directed to make drawings and illustrations of shipyard work and life, and this requirement for realistic documentation strongly affected his later style. Later in the war, classified as a "camoufleur," Benton drew the camouflaged ships that entered Norfolk harbor.[9] His work was required for several reasons: to ensure that U.S. ship painters were correctly applying the camouflage schemes, to aid in identifying U.S. ships that might later be lost, and to have records of the ship camouflage of other Allied navies. Benton later said that his work for the Navy "was the most important thing, so far, I had ever done for myself as an artist."[10]

Marriage and family

At age 33, Benton married Rita Piacenza, an Italian immigrant, in 1922. They met while Benton was teaching art classes for a neighborhood organization in New York City, where she was one of his students. The couple had a son, Thomas Piacenza Benton, born in 1926, and a daughter, Jessie Benton, born in 1939. They were married for almost 53 years until Thomas' death in 1975. Rita died eleven weeks after her husband.

Later career

Dedication to Regionalism

On his return to New York in the early 1920s, Benton declared himself an "enemy of modernism"; he began the naturalistic and representational work today known as Regionalism. Benton was active in leftist politics. He expanded the scale of his Regionalist works, culminating in his America Today murals at the New School for Social Research in 1930-31. In 1984 the murals were purchased and restored by AXA Equitable to hang in the lobby of the AXA Equitable Tower at 1290 Sixth Avenue in New York City.[11] In December 2012 AXA donated the murals to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[12] The Met's exhibition, "Thomas Hart Benton's America Today Mural Rediscovered."[13] will run until April 19, 2015. They show how Benton absorbed and used the influence of the Greek artist El Greco.[14]

Benton broke through to the mainstream in 1932. A relative unknown, he won a commission to paint the murals of Indiana life planned by the state in the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago. The Indiana Murals stirred controversy; Benton painted everyday people, and included a portrayal of events in the state's history which some people did not want publicized. Critics attacked his work for showing Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members in full regalia.[15] The KKK reached its peak membership in 1925. In Indiana, 30% of adult males were estimated to be members of the Klan, and in 1924 KKK members were elected as governor, and to other political offices.[16]

These mural panels are now displayed at Indiana University in Bloomington, with the majority hung in the "Hall of Murals" at the Auditorium. Four additional panels are displayed in the former University Theatre (now the Indiana Cinema) connected to the Auditorium. Two panels, including the one with images of the KKK, are located in a lecture classroom at Woodburn Hall.[15]

In 1932, Benton also painted The Arts of Life in America, a set of large murals for an early site of the Whitney Museum of American Art.[17] Major panels include Arts of the City, Arts of the West, Arts of the South and Indian Arts.[18] In 1953 five of the panels were purchased by the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut, and have since been displayed there.

On December 24, 1934, Benton was featured on one of the earliest color covers of Time magazine.[19] Benton's work was featured along with that of fellow Midwesterners Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry in an article entitled "The U.S. Scene". The trio were featured as the new heroes of American art, and Regionalism was described as a significant art movement.[20]

In 1935, after he had "alienated both the left-leaning community of artists with his disregard for politics and the larger New York-Paris art world with what was considered his folksy style",[4] Benton left the artistic debates of New York for Missouri. He was commissioned to create a mural for the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City. A Social History of Missouri is perhaps Benton’s greatest work. In an interview in 1973, Tom said, "If I have any right to make judgments, I would say that the Missouri mural was my best work".[21] As with his earlier work, controversy arose over his portrayal of the state's history, as he included the subjects of slavery, the Missouri outlaw Jesse James, and the political boss Tom Pendergast. With his return to Missouri, Benton embraced the Regionalist art movement.

He settled in Kansas City, Missouri and accepted a teaching job at the Kansas City Art Institute. This base afforded Benton greater access to rural America, which was changing rapidly. Because of his Populist political upbringing, Benton's sympathy was with the working class and the small farmer, unable to gain material advantage despite the Industrial Revolution.[citation needed] His works often show the melancholy, desperation and beauty of small-town life.[citation needed] In the late 1930s, he created some of his best-known work, including the allegorical nude Persephone. It was considered scandalous by the Kansas City Art Institute, and was borrowed by the showman Billy Rose, who hung it in his New York nightclub, the Diamond Horseshoe.[4] It is now held by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. Karal Ann Marling, an art historian, says it is "one of the great works of American pornography."[4]

In 1937, Benton published his autobiography, An Artist in America, which was critically acclaimed. The writer Sinclair Lewis said of it: “Here’s a rare thing, a painter who can write.” [22] During this period, Benton also began to produce signed, limited edition lithographs, which were sold at $5.00 each through the Associated American Artists Galleries based in New York.[23]

Teaching career

Benton's autobiography indicates that his son was enrolled from age 3–9 at the City and Country School in exchange for his teaching art there.[24] He included Caroline Pratt in "City Activities with Dance Hall," one of the ten panels in "America Today."[25]

Benton taught at the Art Students League of New York from 1926 to 1935 and at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1935 to 1941. His most famous student, Jackson Pollock, whom he mentored in the Art Students League, founded the Abstract Expressionist movement. Pollock often said that Benton's traditional teachings gave him something to rebel against.[26] With another of his students, Glen Rounds, who went on to become a prolific author and illustrator of children's books, Benton spent a summer touring the Western United States in the early 1930s.[27][28]

Benton's students in New York and Kansas City included many painters who contributed significantly to American art. They included Pollock’s brother Charles Pollock, Eric Bransby, Charles Banks Wilson, Frederic James, Lamar Dodd, Reginald Marsh, Charles Green Shaw, Margot Peet, Jackson Lee Nesbitt, Roger Medearis, Glenn Gant, Fuller Potter, and Delmer J. Yoakum.[29] Benton also briefly taught Dennis Hopper at the Kansas City Art Institute; Hopper was later known for being an independent actor, filmmaker, and photographer.[30]

In 1941 Benton was dismissed from the Art Institute after he said the typical art museum was "a graveyard run by a pretty boy with delicate wrists and a swing in his gait."[31] He made additional disparaging references to what he said was the excessive influence of homosexuals (which he called "the third sex") in the art world.[31]

Later life

During World War II, Benton created a series titled The Year of Peril, which portrayed the threat to American ideals by fascism and Nazism. The prints were widely distributed. Following the war, Regionalism fell from favor, eclipsed by the rise of Abstract Expressionism.[32] Benton remained active for another 30 years, but his work included less contemporary social commentary and portrayed pre-industrial farmlands.

Benton was hired in 1940, along with eight other prominent American artists, to document dramatic scenes and characters during the production of the film The Long Voyage Home, a cinematic adaptation of Eugene O'Neill's plays.[33]

Benton was also an accomplished harmonica musician, recording an album for Decca Records in 1942 titled "Saturday Night at Tom Benton's".

He continued to paint murals, including Lincoln (1953), for Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri; Trading At Westport Landing (1956), for The River Club in Kansas City; Father Hennepin at Niagara Falls (1961) for the Power Authority of the State of New York; Turn of the Century, Joplin (1972) in Joplin; and Independence and the Opening of The West, for the Harry S. Truman Library in Independence. His commission for the Truman Library mural led to his developing a friendship with the former U.S. President that lasted for the rest of their lives.

Benton died in 1975 at work in his studio, as he completed his final mural, The Sources of Country Music, for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, Tennessee.[32]

Legacy and honors

Benton was elected into the National Academy of Design in 1954 as an Associate member, and became a full member in 1956.

In 1977, Benton's 2-1/2 story late-Victorian residence and carriage house studio in Kansas City was designated by Missouri as the Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site.[34] The historic site has been preserved nearly unchanged from the time of his death; clothing, furniture, and paint brushes are still in place. Displaying 13 original works of his art, the house museum is open for guided tours.

Benton was the subject of the eponymous 1988 documentary, Thomas Hart Benton, directed by Ken Burns.

Writings

- Benton, Thomas Hart (1951), An Artist in America, University of Kansas City Press.

- Benton, Thomas Hart (1969), An American in Art: A Professional and Technical Autobiography, University Press of Kansas.

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Europe After 8:15 – H.L. Mencken—1914

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Schoolhouse in the Foothills – Ella Enslow—1937

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Tom Sawyer – Mark Twain—1939

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck—1940

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Huckleberry Finn – Mark Twain—1941

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Taps for Private Tussie – Jesse Stuart—1943

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography & Other Tales—1944

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Life on the Mississippi – Mark Twain—1944

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) The Oregon Trail – Francis Parkman—1945

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Ozark Folksongs (4 Vols.) – Vance Randolph (endpapers only) – 1946-50

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) We the People – Leo Huberman—1947

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Green Grow the Lilacs – Lynn Riggs—1954

- (Illustrated by Thomas Hart Benton) Three Rivers South (Young Abe Lincoln) – Virginia Eifert – 1955

References

Notes

- ^ "ULAN Full Record Display: Thomas Hart Benton". Getty Research. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site". Missouri State Parks. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ WETA (2002). "Thomas Hart Benton: Timeline". PBS. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f WETA (2010), Thomas Hart Benton: Benton Profile, PBS, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ http://mostateparks.com/page/55154/benton-genealogy

- ^ Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, University of Missouri Press, 1999, pg. 62

- ^ benton.truman.edu

- ^ Craven, Wayne (2003), American Art: History and Culture, McGraw-Hill, p. 439, ISBN 978-0-697-16763-7.

- ^ http://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/visual-arts/article345869/Exhibit-on-artist-Thomas-Hart-Benton-highlights-influence-from-Navy-stint.html

- ^ An Artist in America, Thomas Hart Benton, University of Missouri Press, p. 44

- ^ "The Collection", AXA Gallery, accessed 2 August 2012

- ^ [1]"AXA Equitable Donates America Today, Thomas Hart Benton’s Epic Mural Cycle Celebrating Life in 1920s America, to Metropolitan Museum"

- ^ http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/thomas-hart-benton

- ^ Craven 2003, p. 440

- ^ a b Indiana University (July 27, 2009), IU Art Museum opens doors to conservation of famed Thomas Benton murals, IU News Room, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ "Ku Klux Klan in Indiana". Indiana State Library. November 2000. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ The Murals of Thomas Hart Benton, New Britain Museum of American Art, 2010, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ A Glimpse of the Five Major Panels, New Britain Museum of American Art, 2010, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ For an online reproduction of the cover, see TIME Magazine Cover: Thomas Hart Benton, Time Archive: 1913 to the present, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ "The U.S. Scene", Time, December 24, 1934, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ American Heritage magazine, June 1973, page 87.

- ^ "Slim, Jim, and Lem", Newsweek, November 1, 1937, p. 25

- ^ The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton. Compiled and edited by Creekmore Fath. University of Texas Press, 1969, p. 3.

- ^ [2] "Learning from Children: The Life and Legacy of Caroline Pratt, p. 131 by Mary Huaser Peter Lang Publishers, 2006"

- ^ [3] "Caroline Pratt and Thomas Hart Benton Go to the MET"

- ^ Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, p. 137, ed. Clifford Ross, Abrahams Publishers, New York 1990

- ^ "Glen Rounds". North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ "Malcolm Blue Society Celebrates 40 Years". ThePilot.com. 8 July 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ^ Marianne Berardi, Under the Influence: The Students of Thomas Hart Benton, Kansas City: The Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, 1993

- ^ Gross, Terry (June 1, 2010), "Anarchic Actor, Artist Dennis Hopper, 1936-2010", Fresh Air, National Public Radio, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "Benton Hates Museums", Time, April 14, 1941, retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "Thomas Hart Benton Biography". New Britain Museum of American Art. 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ "Cover Article, American Artist Magazine, September, 1940, pp. 4-14"

- ^ "Kansas City Attractions: Thomas Hart Benton Home". Frommer's USA, 10th edition,. The New York Times. 2007. ISBN 978-0-470-04726-2.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) [dead link]

Catalogs and monographs

- Benton, Thomas Hart; Craven, Thomas (1939), Thomas Hart Benton: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Works of Thomas Hart Benton, Spotlighting the Important Periods during the Artist's Thirty-two Years of Painting, with an Examination of the Artist and His Work, Associated American Artists

- University of Kansas Museum of Art (1958), Thomas Hart Benton: A Retrospective Exhibition of the Works of the Noted Missouri Artist Presented under the Patronage of Harry S. Truman and Mrs. Truman of Independence, Missouri, April 12 to May 18, 1958

Major Museum Exhibitions

- "Thomas Hart Benton's 'America Today' Mural Rediscovered," organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[1]

- "American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood," organized by the Peabody Essex Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art[2]

Further reading

- Adams, Henry, "Thomas Hart Benton's Fall from Grace," Missouri Historical Review, 109 (April 2015), 145-57. Heavily illustrated.

- Adams, Henry (1989), Thomas Hart Benton: An American original, Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-57153-3

- Adams, Henry; Henry Art Gallery (1990), Thomas Hart Benton: Drawing from Life, Abbeville Press, ISBN 978-1-55859-011-3

- Adams, Henry (2009), Tom and Jack: The Intertwined Lives of Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, ISBN 978-1-59691-420-9

- Baigell, Thomas (1975), Thomas Hart Benton, H. N. Abrams, ISBN 978-0-8109-2055-2

- Berardi, Marianne; Adams, Henry (1993), Under the Influence: The Students of Thomas Hart Benton, Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, ISBN 978-0-9615372-2-7

- Foster, Kathy A.; Brewer, Nanette Esseck; Contompasis, Margaret (2001), Thomas Hart Benton and the Indiana Murals, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-33760-3

- Low, Sam (July 2004). "It freed his heart". Martha's Vineyard Magazine. pp. 45–51, 92.

It wasn't until Thomas Hart Benton came to the island in 1920 that he found himself, and the painting style for which he would become famous.

- Wolff, Justin (2012), Thomas Hart Benton: A Life, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-19987-6

External links

- Works by Thomas Hart Benton in the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- Thomas Hart Benton papers, 1906-1975 from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- "Thomas Hart Benton: America Today", AXA Gallery-Press Release, AXA Gallery

- Works by Thomas Hart Benton at the State Historical Society of Missouri

- The Long Voyage Home Artist Portraits and Paintings at The Ned Scott Archive

- Works by Thomas Hart Benton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Hart Benton at the Internet Archive

- ^ "Thomas Hart Benton'sAmerica Today Mural Rediscovered | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ^ "American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood » The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art". The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- American muralists

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- Modern painters

- People of the New Deal arts projects

- United States Navy sailors

- American naval personnel of World War I

- Alumni of the Académie Julian

- Art Students League of New York faculty

- School of the Art Institute of Chicago alumni

- Kansas City Art Institute alumni

- People from Neosho, Missouri

- Artists from Kansas City, Missouri

- 1889 births

- 1975 deaths

- Painters from Missouri

- Writers from Missouri

- 20th-century American printmakers