Trifunctional hypothesis

The trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European society postulates a tripartite ideology ("idéologie tripartite") reflected in the existence of three classes or castes—priests, warriors, and commoners (farmers or tradesmen)—corresponding to the three functions of the sacral, the martial and the economic, respectively. This thesis is especially associated with the French mythographer Georges Dumézil[1] who proposed it in 1929 in the book Flamen-Brahman,[2] and later in Mitra-Varuna.[3]

Three-way division

According to Dumézil, Proto-Indo-European society comprised three main groups corresponding to three distinct functions: the first is associated with the function of sovereignty, another with the military function, and a third with that of productivity. Sovereignty fell into two distinct and complementary sub-parts, one formal, juridical and priestly but worldly, the other powerful, unpredictable, and also priestly but rooted in the supernatural world. The second main division was connected with force, the military and war while the role of the third, ruled by the other two, was productivity, herding, farming and crafts.[2][3] Its mythology was divided in the same way: each social group had its own god or family of gods to represent it and the function of the god or gods matched the function of the group.

Many such divisions occur in various contexts of early history.

- One example is the supposed division between the king, nobility and regular freemen in early Germanic society[4]

- Plato's tripartite theory of soul is proposed in The Republic, where Plato argues that the soul is composed of three parts: the rational, the spirited, the appetitive. These three parts correspond to the three classes of a just society, each of which is characterized by the predominance of a given part of the soul.[5]

- Three Hindu castes, the Brahmans or priests, the Kshatriya—those with governing functions—and the Vaishya—the agriculturalists, cattle rearers and traders—are associated the three philosophical qualities (gunas), Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas respectively. The castes are socio-economic roles filled by members of society.[6] The Shudra, a fourth caste, is an "outer" or serf caste serving the other three. A 2001 study found that the genetic affinity of Indians to Europeans is proportionate to caste rank, the upper castes being most similar to Europeans whereas lower castes are more like Asians. The researchers believe that the Indo-European speakers entered India from the Northwest, mixing with or displacing proto-Dravidian speakers, and may have established a caste system with themselves primarily in higher castes.[7]

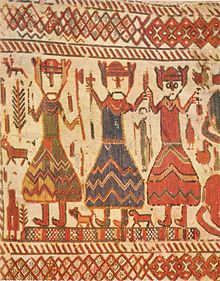

- Terje Leiren believes a grouping of three Norse gods can be discerned that corresponds to the trifunctional division; Odin as the patron of priests and magicians, Thor of warriors, and Freyr of fertility and farming.[8]

- Bernard Sergent associates the Indo-European language family with certain archaeological cultures in Southern Russia and reconstructs an Indo-European religion based upon the tripartite functions.[9] He has also examined the trifunctional hypothesis in Greek epic, lyric and dramatic poetry.[10]

Reception

Supporters of the hypothesis include scholars such as Bernard Sergent and Iaroslav Lebedynsky, who concludes that "the basic idea seems proven in a convincing way".[11] The endorsement of C. Scott Littleton[12] was criticized by Lincoln[13] as "bordering on hagiography".

The hypothesis was embraced outside the field of Indo-European studies by some mythographers, anthropologists, and historians such as Mircea Eliade, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Marshall Sahlins, Rodney Needham, Jean-Pierre Vernant and Georges Duby.[13]

On the other hand, Allen[14] concludes that the tripartite division may be an artefact, a selection effect rather than an organizing principle used in the societies themselves. Benjamin W. Fortson reports[15] a sense that Dumézil blurred the lines between the three functions and the examples that he gave often had contradictory characteristics, causing detractors[16] to reject his categories as non-existent. John Brough surmises that societal divisions are common outside of Indo-European societies as well, and consequently the hypothesis has only limited utility in illuminating prehistoric Indo-European society.[17] Cristiano Grottanelli states that while Dumézilian trifunctionalism may be seen in modern and medieval contexts, its projection onto earlier cultures is mistaken.[18] Belier is strongly critical.[19]

The hypothesis has been criticised by historians Carlo Ginzburg, Arnaldo Momigliano[20] and Bruce Lincoln[21] as being based on Dumézil's sympathies with the political right. Guy G. Stroumsa sees these criticisms as unfounded[22] and Stefan Ardvidsson credits Dumézil with enough skill as a writer to separate his research from his ideological beliefs, though he notes that Dumézil is known to have supported French group Action Française and to have used a pseudonym whilst writing in praise of Benito Mussolini.[21]

References

- ^ According to Jean Boissel, the first description of Indo-European trifunctionalism was by Gobineau, not by Dumézil. (Lincoln, 1999, p. 268, cited below).

- ^ a b Dumézil, G. (1929). Flamen-Brahman.

- ^ a b Dumézil, G. (1940). Mitra-Varuna, Presses universitaires de France.

- ^ Dumézil, Georges. (1958). The Rígsþula and Indo-European Social Structure. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Ed. Einar Haugen, trans. John Lindow (1973). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03507-0.

- ^ "Plato's Ethics and Politics in The Republic" at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Retrieved August 29, 2009

- ^ [1]

- ^ Bamshad, Michael (2001). "Genetic Evidence on the Origins of Indian Caste Populations". Gnome Research. 11 (6): 994–1004. doi:10.1101/gr.GR-1733RR. PMC 311057. PMID 11381027. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leiren, Terje I. (1999). From Pagan to Christian: The Story in the 12th-Century Tapestry of the Skog Church. Published online: http://faculty.washington.edu/leiren/vikings2.html

- ^ Bernard Sergent, Les Indo-Européens - Histoire, langues, mythes, Payot, 1995 ISBN 2228889563

- ^ In the monograph Les trois fonctions indo-européennes en Grèce ancienne Vol. 1, De Mycènes aux Tragique, Économica 1998 ISBN 2717835873

- ^ Lebedynsky, I.. (2006). Les Indo-Européens, éditions Errance, Paris

- ^ Littleton, C. S. (1966). The New Comparative Mythology: An Anthropological Assessment of the Theories of Georges Dumézil, University of California Press, (3rd ed. 1982).

- ^ a b Lincoln, B. (1999). Theorizing myth: Narrative, ideology, and scholarship, p. 260 n. 17. University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-48202-6.

- ^ Allen, N. J. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2007.10.53

- ^ Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction p. 32

- ^ Gonda, J. (1974). Dumezil's Tripartite Ideology: Some Critical Observations. The Journal of Asian Studies, 34 (1), 139–149, (Nov 1974).

- ^ Lindow, J. (2002). Norse mythology: a guide to the Gods, heroes, rituals, and beliefs, p. 32. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-515382-8.

- ^ Grottanelli, Cristiano. Dumézil and the Third Function. In Myth and Method.

- ^ Belier, W. W. (1991). Decayed Gods: Origin and Development of Georges Dumézil's Idéologie Tripartite, Leiden.

- ^ Wolin, Richard. The seduction of unreason: the intellectual romance with fascism, p. 344

- ^ a b Arvidsson, Stefan. Aryan idols: Indo-European mythology as ideology and science, p. 3

- ^ Stroumsa, Guy G. (1998). Georges Dumézil, ancient German myths, and modern demons. Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft, 6, 125-136.[2]