Třeboň Altarpiece

The Třeboň Altarpiece, also known as Wittingau altarpiece, is one of the most important works of European Gothic panel painting.[1] Of the original large altarpiece retable created in about 1380 by an anonymous Gothic painter called the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece, three wings, painted on both sides, have survived. The altarpiece is one of the works that helped towards the emergence of the International Gothic style (called the Beautiful Style in the Bohemian lands) and which influenced the development of art in a broad European context.[2][3]

It was created for the Augustinian Church of St Giles in Třeboň and is now part of the permanent collection of medieval art of the National Gallery in Prague.

Altarpiece[edit]

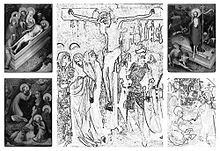

Reconstruction[edit]

The three surviving wings could have formed part of a large altarpiece with the Crucifixion as its central part. On the missing fourth wing there would most probably have been a scene following on from the Resurrection of Christ, for example Noli Me Tangere (the altarpiece was consecrated to St Mary Magdalene).[4] A number of researchers have focused on reconstructing the arrangement of the panels; variations have been proposed with the central painting of the Crucifixion, similar to smaller works from the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece workshop and followers (the Crucifixion from St Barbara’s Church, the Crucifixion from Vyšší Brod[5]), with sculptural decoration or a variation with two paintings similar to the later Rajhrad Altarpiece (the Crucifixion and Christ Carrying the Cross) and the Graudenz Altarpiece.[6] The original winged altarpiece could have been more than 3 metres high, with a pair of wings above each other. The open altarpiece, with Passion scenes unified by a red background, invited worshippers to meditate as individuals. The rear side of the wings with paintings of male and female saints, visible when the altar was closed, is most probably connected with the consecration of the church and its chapels, as well as with the patron saints of the order and the holy relics kept in the church.

Material and technique[edit]

The quality of the Třeboň Altarpiece's painting is without parallel and represents the technological pinnacle of European painting in the late 14th century.[7] The material, painting technique and panel size (height 132 cm, width 92 cm) are the same in all the surviving panels. The panels are composed of spruce boards joined by pegs and covered on both sides with canvas. The ground is formed by a basic layer of coarser-grained silicate clay and another layer of fine chalk. The preparatory drawing is executed in brush with iron-red pigment; the engraved lines only mark the architectural elements. The gilding is executed without poliment, using an oily bonding agent. All the gilded areas have the same type of punched decoration.[8] In contrast to earlier panel painting, the painter used lead white underpainting only in specific places, instead modelling the portraits and drapery by gradually building up translucent layers of egg tempera. Linseed oil was used to bond the pigments.[9]

Front side[edit]

The composition is dominated by the striking diagonal of the rock faces that divide the central figure of Christ from the two accompanying scenes: the sleeping apostles in the foreground and Judas bringing the soldiers in the background. The praying Christ has drops of bloody sweat (the Gospel of St Luke) and the angel presents him with the Cup of Bitterness. The scale of Christ's body stands out from the pictorial space and is not subject to the same order as the others. It is dressed in the brownish robe of a penitent and the modelling in light and chiaroscuro painting suppresses its physical substance. Depicted in a hieratical perspective with the central figure of Christ, the landscape is merely an accompanying part of the composition. In comparison with earlier simplistically depicted crystalline rock faces (the Vyšší Brod (Hohenfurth) cycle) however, this landscape comes closer to reality. Great attention is devoted to the modelling of the terrain and to small details.

Christ, who is portrayed as an almost immaterial figure swathed in transparent fabric, is laid in the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus. The Virgin Mary, who is being supported by St John, has the appearance of a young woman. Her blood-spattered headdress recalls Christ's torment on the cross. The woman standing on the left is Mary Magdalene and, behind her, Mary of Cleophas (the Gospels of St Matthew and St Luke), the mother of St James the Younger, turns towards St John. All the figures experience grief individually. This conception corresponds with the period of the late 14th century and the Augustinian movement Devotio Moderna that encouraged the faithful to seek personal piety. Along with the rocks and rock ravine, the sarcophagus creates a striking diagonal that deepens space. Details in the landscape and the illusive painting of the marble sarcophagus are painstakingly executed.

Christ in his glory as the Redeemer and a levitating divine manifestation is freed of all bodily and earthly weight.[10] He is immobile and exists outside earthly time, however the shadow he casts behind him recalls his human origin. The Easter miracle of the Resurrection is also symbolised by the unbroken seals on the sarcophagus. Christ is made vividly present to believers by the amazed expressions on the faces of the guards who have been woken up.

The iconographic scheme of the Resurrection with a closed and sealed tomb has a literary origin. It became important and influential through the interpretation of St Augustine in particular.[11] This specific interpretation can also be a reference to one of Konrad Waldhauser's Easter sermons. The diagonal is suppressed in this composition in order to place greater emphasis on the vertical figure of Christ. The radiant colours with the dominant red of the robe and the light that Christ radiates contrast with the grey background of the landscape that is the setting in which earthly figures are situated. Red has symbolic meaning as the colour of the Eucharist as also as the colour of victory on Christ's banner.

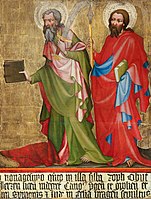

Reverse panels[edit]

The original arrangement in all likelihood respected the heavenly hierarchy (according to Pseudo-Dionysius): the apostles, male and female saints (Confessors). On the missing fourth wing there could have been figures of martyr saints (such as St Stephen, St. Callixtus and St Lawrence).[12] The painter represented striking types of faces that were noble, serious and inwardly focused. He also depicted rich garments pleated into complex folds. The faces of the saints have an individual appearance and their psychological state of ‘exalted spiritualisation’ is also portrayed.[13] In terms of their portrait character and the time they were made, these faces have much in common with Petr Parler’s busts in the triforium of St Vitus Cathedral. The stylisation of the drapery is plastic, though it no longer maintains a functional connection with the body. The colour scheme is more symbolic in character and lacking in major contrasts. It thus anticipates the International Gothic style, which is a synthesis of precise observation and free imagination, individual characterisation and a universal idealised type.[14]

The female saints are portrayed under an architectural canopy with a decorated relief. The figures themselves are not firmly fixed on the ground and their robes do not trace their figures; instead, they are a loose play of folds. The faces of the saints represent the period ideal of female beauty and they are physiognomically differentiated. Mary Magdalene, to whom the altarpiece was consecrated, occupies the place of honour in the centre. St Giles was the saint to whom the Třeboň church was consecrated; St Augustine and St Jerome (the translator of the Bible) were venerated as Fathers of the Church and Patron Saints of the Augustinian Canons. Three of Christ's twelve apostles. The feast of St James, who is attributed with a vision of the resurrected Christ, is celebrated together with the feast of St Phillip. St Bartholomew was a close friend of St Phillip and became an apostle after meeting the resurrected Christ. The reason for choosing these three saints could be connected with the relics that were venerated at the Church of St Giles in Třeboň.[citation needed]

Painting style[edit]

The Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece follows on from the earlier panel painting of Master Theodoric of the 1360s and 1370s. He also followed on from the wall paintings of Karlštejn Castle, in particular the Apocalypse series in the Chapel of the Virgin Mary. It is possible that the anonymous Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece was initially active in Master Theodoric’s workshop, where he would have also learned about Franco-Flemish art through Nicholas Wurmser of Strasbourg. Colour, which predominated over drawing, became his chief means of expression. He achieved the deepening of colour tone through the gradual application of translucent layers.

The painter abandoned the linear drawing-based style and used soft colour tones and chiaroscuro painting in which light, falling from somewhere above, unifies the picture and works more as a principle than a natural phenomenon. By using chiaroscuro, he achieves the suppression of the outline, the dematerialisation of the figure of Christ and its release from the space of the picture. In the Resurrection, he was one of the first painters to depict a cast shadow. Interest in details and elements observed from reality are typical of Franco-Flemish art, as is the symbolic red background with gold stars replacing the night sky in the Passion series.

The soft and plastic landscape comes close to reality, but only creates an accompanying scene and is an expression of transcendental idealism – an illustration of a prayer ascending to heaven.[15] The artist's personal aim is the emotional impact of the picture, the emotional interpretation of religious themes and a profound personal experience as well as an effort to achieve the extreme refinement of the human appearance. With its overall softening of portrayal, transcending of localised colour and bringing the image closer to specific optical experience, this work marks the nascence of the International Gothic and its Bohemian variation – the Beautiful Style.[16]

The work of the Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece is marked by aestheticizing trends characteristic of certain forms of expression in the 1370s and 1380s (Heinrich of Gmünd, wall paintings), by a harmony of proportion between forms and colour, as well as by a greater degree of stylisation. According to Augustine's theocentric aesthetics, bodily beauty is a mere glint of the higher beauty; it is subject to time and changes while true beauty is absolute and beyond time (Conversations of the Soul with God, chapter 5). St Augustin brought closer, and almost made identical, the notion of art and the notion of beauty; and, in this sense, he saw the mission and function of art in the creation of beauty.[17] The Augustinian Order became the bearer of the Devotio Moderna, an orientation combining a deepened personal piety with Augustinian beliefs and early humanism, and also placing great emphasis on aesthetic values. The supreme beauty of the faces of the International Gothic female saints and Madonnas is a beauty beyond earthly space and time. The Třeboň Master used an expressional evaluation of artistic convention that is characteristic of a period of transformation in style.[18]

The composition of all the panels of the Passion series is based on a striking diagonal directed towards the central part of the altarpiece. The deepened space is not constructed according to optical laws; instead, the impression of depth is evoked by the diagonally inserted substance of the rock faces and sarcophagus.[19] Christ is the central figure of each composition; he also stands out from the typology of the other figures, divided as they are between the ugly, realistic faces of the soldiers and the beautiful, soft faces of the female saints and the Virgin Mary.

The history of the altarpiece[edit]

It was most probably Jan of Jenštejn, the third Prague archbishop, who recommended the painter to the Augustinians in Roudnice (the Roudnice Madonna) who founded the monastery in Třeboň. A written record of the consecration of the altarpiece in 1378 (A.D. MCCCLXXVIII consecratum est hoc altare...) has survived. The altarpiece was dismantled in 1730; in the place where it had stood, relics connected with the consecration of the Church of St Giles were discovered. The individual panels were dispersed to smaller churches in the surrounding area.

The first two panels (The Mount of Olives, The Resurrection) come from the church in Svatá Majdalena near Třeboň, where they were discovered by J. A. Beck (1843); they were rescued by Jan Erazim Wocel (1858). In 1872 they were purchased by Count A. Kaunic and JUDr. K. Schäffner for the Picture Gallery of the Society of Patriotic Friends of Art. The third panel (The Entombment) from the chapel in Domanín, where in 1895 it served as an altar painting, was acquired for the state collection in 1921.

Related works[edit]

-

Madonna between St Bartholomew and St Margaret, Aleš South Bohemian Gallery in Hluboká nad Vltavou

-

Enthroned Madonna from Hradec Králové, National Gallery in Prague

-

Madonna, Epitaph of Jan of Jeřeň, National Gallery in Prague

-

St Bartholomew, St Thomas, Epitaph of Jan of Jeřeň, National Gallery in Prague

Notes[edit]

- ^ Royt, 2014, p. 13

- ^ Kutal A,1972, p. 127

- ^ Kateřina Kubínová, in: Petrasová T, Švácha R, 2017, p. 217

- ^ Jan Royt, 2014, p. 142-146

- ^ Royt J, 2014, pp. 98-99

- ^ Royt, 2014, p. 142

- ^ "Novák A, Mistr třeboňského oltáře. Funkce pojidla ve světelné aktivizaci barevné vrstvy, Technologia Artis 1". Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- ^ Frinta M S, 1998

- ^ Adam Pokorný, The master of the Třeboň Altarpiece painting technique, in: Royt J, 2014, s. 239-248

- ^ Homolka J, 1979/80, p. 27

- ^ Homolka J, 1979/80 p. 31

- ^ Royt J, 2014, p. 133-149

- ^ Matějček A, 1950, s. 92

- ^ Kutal A, 1970, s. 127

- ^ Matějček A, 1950, p. 90

- ^ Homolka J, 1979/80, p. 25

- ^ Homolka J, 1979/80, p. 30

- ^ Homolka J, 1979/80, p. 27

- ^ Kutal A, 1972, p. 127

Sources[edit]

- Prof. PhDr. Ing. Jan Royt, PhD, Mistr Třeboňského oltáře (Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece), dissertation thesis to acquire the academic title ‘Doctor of Sciences’ in the history sciences group, Institute of Art History of the Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, Institute of the History of Christian Art, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 2014

- Jan Royt, Mistr Třeboňského oltáře, Karolinum Press, Prague 2014, ISBN 978-80-246-2261-3

- Mojmír Svatopluk Frinta, Punched Decoration on Late Medieval Panel and Miniature Painting, Maxdorf, Prague, 1998

- Jaromír Homolka, Poznámky k Třeboňskému mistrovi (Notes on the Třeboň Master), SBORNÍK PRACÍ FILOZOFICKÉ FAKULTY BRNĚNSKÉ UNIVERZITY [Anthology of Works of the Faculty of Arts of Brno University], STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS BRUNENSIS, F 23/24, 1979/80

- Přibíková Helena, Mistr Třeboňského oltáře, Pokus o genesi jeho tvorby v českém výtvarném a duchovním prostředí doby Karla IV. [The Master of the Třeboň Altarpiece, An Attempt at Ascertaining the Genesis of His Work in the Bohemian Artistic and Spiritual Milieu of the Era of Charles IV], graduation thesis, Philosophy Faculty of Charles University, 1972

- Albert Kutal, České gotické umění (Bohemian Gothic Art), Artia/Obelisk, Prague 1972

- Jaroslav Pešina (ed.), České umění gotické 1350-1420 (Bohemian Gothic Art 1350-1420), Academia, Prague 1970

- Vladimír Denkstein, František Matouš, Jihočeská gotika (South Bohemian Gothic), SNKLHU Prague, 1953

- Antonín Matějček, Jaroslav Pešina, Česká malba gotická (Bohemian Gothic Painting), Melantrich, Prague 1950, pp. 89–101

- Antonín Matějček, Le Maître de Trebon, Les Peintres Célèbres. Geneva-Paris, 1948