USS Congress (1799)

Congress by Charles Ware, 1816

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Congress |

| Namesake | Congress[1] |

| Ordered | 27 March 1794[1] |

| Builder | James Hackett |

| Cost | $197,246[2] |

| Laid down | 1795[3] |

| Launched | 15 August 1799 |

| Maiden voyage | 6 January 1800 |

| Fate | Broken up, 1834 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | 38-gun frigate[4][5][Note 1] |

| Displacement | 1,265 tons[1] |

| Length | 164 ft (50 m) lpp[4] |

| Beam | 41 ft (12 m)[4] |

| Depth of hold | 13.0 ft (4.0 m)[4] |

| Decks | Orlop, Berth, Gun, Spar |

| Propulsion | Sail |

| Complement | 340 officers and enlisted[1] |

| Armament |

|

USS Congress was a nominally rated 38-gun wooden-hulled, three-masted heavy frigate of the United States Navy. She was named by George Washington to reflect a principal of the United States Constitution. James Hackett built her in Portsmouth New Hampshire and she was launched on 15 August 1799. She was one of the original six frigates whose construction the Naval Act of 1794 had authorized. Joshua Humphreys designed these frigates to be the young Navy's capital ships, and so Congress and her sisters were larger and more heavily armed and built than the standard frigates of the period.

Her first duties with the newly formed United States Navy were to provide protection for American merchant shipping during the Quasi War with France and to defeat the Barbary pirates in the First Barbary War. During the War of 1812 she made several extended length cruises in company with her sister ship President and captured, or assisted in the capture of twenty British merchant ships. At the end of 1813, due to a lack of materials to repair her, she was placed in ordinary for the remainder of the war. In 1815 she returned to service for the Second Barbary War and made patrols through 1816. In the 1820s she helped suppress piracy in the West Indies, made several voyages to South America, and was the first U.S. warship to visit China. Congress spent her last ten years of service as a receiving ship until ordered broken up in 1834.

Construction

In 1785 Barbary pirates, most notably from Algiers, began to seize American merchant vessels in the Mediterranean. In 1793 alone, eleven American ships were captured and their crews and stores held for ransom. To combat this problem, proposals were made for warships to protect American shipping, resulting in the Naval Act of 1794.[6][7] The act provided funds to construct six frigates, but included a clause that if peace terms were agreed to with Algiers, the construction of the ships would be halted.[8][9]

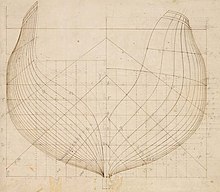

Joshua Humphreys' design was unusual for the time, being long on keel and narrow of beam (width) and mounting very heavy guns. The design called for a diagonal scantling (rib) scheme intended to restrict hogging while giving the ships extremely heavy planking. This design gave the hull a greater strength than a more lightly built frigate. Humphreys' design was based on his realization that the fledgling United States of the period could not match the European states in the size of their navies. This being so, the frigates were designed to overpower other frigates with the ability to escape from a ship of the line.[10][11][12]

Congress was given her name by President George Washington after a principle of the United States Constitution.[8][13] Her keel was reportedly laid down late in 1795[3] at a shipyard in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. James Hackett was charged with her construction and Captain James Sever served as a superintendent. Her construction proceeded slowly and was completely suspended when in March 1796, a peace treaty was signed with Algiers.[14][15] Congress remained at the shipyard, incomplete, until relations with France deteriorated in 1798 with the start of the Quasi-War. At the request of then President John Adams, funds were approved on 16 July to complete her construction.[16]

Armament

The Naval Act of 1794 had specified 36-gun frigates. However, Congress and her sister-ship Constellation were re-rated to 38s because of their large dimensions, being 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12 m) in width.[4][5][Note 1]

The "ratings" by number of guns were meant only as an approximation, and Congress often carried up to 48 guns.[18] Ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns such as modern Navy ships carry. The guns and cannons were designed to be completely portable and often were exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer outfitted armaments to their liking, taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, the armaments on ships would change often during their careers, and records of the changes were not generally kept.[19]

During her first cruise in the Quasi-War against France, Congress was noted to be armed with a battery of forty guns consisting of twenty-eight 18 pounders (8 kg) and twelve 9 pounders (4 kg).[17] For her patrols during the War of 1812, she was armed with a battery of forty-four guns consisting of twenty-four 18 pounders and twenty 32 pounders (15 kg).[17]

Quasi-War

Congress launched on 15 August 1799 under the command of Captain Sever. After fitting-out in Rhode Island, she set off on her maiden voyage 6 January 1800 sailing in company with Essex to escort merchant ships to the East Indies.[20][21] Six days later she lost all of her masts during a gale. Because her rigging had been set and tightened in a cold climate, it had slackened once she reached warmer temperatures.[22] Without the full support of the rigging, all the masts fell during a four-hour period, killing one crew member trying to repair the main mast.[23][24]

The crew rigged an emergency sail and limped back to the Gosport Navy Yard for repairs.[25] While there, some of Sever's junior officers announced that they had no confidence in his ability as a commanding officer. A hearing was held, and Captain Sever was cleared of any wrongdoing and remained in command of Congress, though many of his crew soon transferred out to Chesapeake.[25][26]

Remaining in port for six months while her masts and rigging were repaired, she finally sailed again on 26 July for the West Indies.[27] Congress made routine patrols escorting American merchant ships and seeking out French ships to capture. On two occasions she almost ran aground; first while pursuing a French privateer, she ran into shallow water where large rocks were seen near the surface.[24] Although their exact depth was not determined, Sever immediately abandoned pursuit of the privateer and changed course towards deeper waters.[28] Her second close call occurred off the coast of the Caicos Islands, when during the night she drifted close to the reefs. At daybreak her predicament was discovered by the lookouts.[29][Note 2]

A peace treaty with France was ratified on 3 February 1801 and Congress returned to Boston in April.[31] In accordance with an act of Congress passed on 3 March and signed by President John Adams, thirteen frigates then currently in service were to be retained. Seven of those frigates, including Congress, were to be placed in ordinary.[32] En route to the Washington Navy Yard, she passed Mount Vernon on her way up the Potomac and Captain Sever ordered her sails lowered, flag at half mast, and a 13-gun salute fired to honor the recently deceased George Washington.[33] Congress decommissioned at Washington along with United States and New York.[33][34][35]

First Barbary War

During the United States' preoccupation with France during the Quasi-War, troubles with the Barbary States were suppressed by the payment of tribute to ensure that American merchant ships were not harassed and seized.[36] In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute he was receiving in comparison to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000.[37] In response, Thomas Jefferson sent a squadron of frigates to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and pursue peace with the Barbary States.[38][39]

The first squadron, under the command of Richard Dale in President, was instructed to escort merchant ships through the Mediterranean and negotiate with leaders of the Barbary States.[38] A second squadron was assembled under the command of Richard Valentine Morris in Chesapeake however, the performance of Morris's squadron was so poor that he was recalled and subsequently dismissed from the Navy in 1803.[40] A third squadron was assembled under the command of Edward Preble in Constitution and by mid-1804 they had successfully fought the Battle of Tripoli Harbor.[41]

President Jefferson reinforced Preble's squadron in April and ordered four frigates to sail as soon as possible. President, Congress, Constellation and Essex were placed under the direction of Commodore Samuel Barron.[41] Congress was captained by John Rodgers and two months were spent preparing the squadron for the voyage. They departed in late June[42] and arrived at Gibraltar on 12 August. Congress and Essex were immediately sent to patrol off the coast of Tangier and when they returned to Gibraltar two weeks later, Congress continued on to Tripoli.[43][44]

Congress, accompanied by Constellation, assumed blockade duties of Tripoli and captured one xebec before sailing for Malta on 25 October for repairs.[44] On 6 November Rodgers assumed command of Constitution and in his place, Stephen Decatur assumed command of Congress.[45] The next recorded activity of Congress is in early July 1805 when she was sent in company with Vixen to blockade Tunisia. They were joined on the 23rd by additional U.S. Navy vessels.[46][Note 3] In early September, Congress carried the Tunisian ambassador back to Washington DC.[47][48] Afterward, placed in ordinary at the Washington Navy Yard, she served as a classroom for midshipmen training through 1807.[49]

War of 1812

In 1811 Congress required extensive repairs before recommissioning with Captain John Rogers in command. She performed routine patrols early in 1812 before war was declared on 18 June. Upon the declaration she was assigned to the squadron of Commodore Rodgers sailing in company with Argus, Hornet, President and United States.[1][50][51]

Almost immediately Rogers was informed by a passing American merchant ship of a fleet of British merchantmen en route to Britain from Jamaica. Congress sailed along in pursuit, but was interrupted when President began pursuing HMS Belvidera on 23 June.[52][53] Congress trailed behind President during the chase and fired her bowchasers at the escaping Belvidera.[54] Unable to capture Belvidera, the squadron returned to the pursuit of the Jamaican fleet. On 1 July they began to follow a trail of coconut shells and orange peels the Jamaican fleet had left behind them.[55][56] Sailing to within one day's journey of the English Channel, the squadron never sighted the convoy and Rodgers called off the pursuit on the 13th. During their return trip to Boston, Congress assisted in the capture of seven merchant ships, including the recapture of an American vessel.[56][57][58]

Making her second cruise against the British with President, Congress sailed from Boston on 8 October. On the 31st of that month, both ships began to pursue HMS Galatea, which was escorting two merchant ships. Galatea and her charges were chased for about three hours, during which Congress captured the merchant ship Argo. In the meantime, President kept after Galatea but lost sight of her as darkness fell. Congress and President remained together during November but they did not find a single ship to capture. On their return to the United States they passed north of Bermuda, proceeded towards the Virginia capes, and arrived back in Boston on 31 December. During their entire time at sea, the two frigates captured nine prizes.[1][59]

Congress and President were blockaded in Boston by the Royal Navy until they slipped through the blockade on 30 April 1813 and put to sea for their third cruise of the war. On 2 May they pursued HMS Curlew but she outran them both and escaped. Congress parted company with President on the 8th and patrolled off the Cape Verde Islands and the coast of Brazil. She only captured four small British merchant ships during this period and returned to the Portsmouth Navy Yard for repairs in late 1813. By this time of the war, materials and personnel were being diverted to the Great Lakes, which created a shortage of resources necessary to repair her. Due to the amount of repairs she needed, it was decided instead to place her in ordinary, where she stayed for the remainder of the war.[60][61][62]

Second Barbary War

Soon after the United States declared war against Britain in 1812, Algiers took advantage of the United States' preoccupation with Britain and began intercepting American merchant ships in the Mediterranean.[63] On 2 March 1815, at the request of President James Madison, Congress declared war on Algiers. Work preparing two American squadrons promptly began—one at Boston under Commodore William Bainbridge, and one at New York under Commodore Steven Decatur.[64][65]

Captain Charles Morris assumed command of Congress and assigned to the squadron under Bainbridge. After repairs and refitting, she transported the Minister to Holland William Eustis to his new post. Congress departed in June and after a few weeks at Holland, sailed for the Mediterranean and arrived at Cartagena, Spain in early August joining Bainbridge's squadron.[66][67] By the time of Congress's arrival, however, Commodore Decatur had already secured a peace treaty with Algiers.[68][69]

Congress, Erie, Chippewa and Spark sailed in company with Bainbridge's flagship Independence—the first commissioned ship of the line of the U.S. Navy—as a show of force off Algiers.[69][70] The squadron subsequently made appearances off Tripoli and Tunis and arrived at Gibraltar in early October.[68][71] From there, Congress and many other ships were ordered back to the United States. She arrived at Newport, Rhode Island, remained there shortly, and proceeded to Boston where she decommissioned in December and assigned to ordinary.[72][73]

Later career

In June 1816 Charles Morris again commanded Congress and began preparations for a cruise to the Pacific Coast of the United States. His objective was taking possession of Fort Astoria from the British and conducting inquiries at various ports along the coast to further improve commercial trade.[74][75][76] These plans were canceled, however, when a U.S. Navy ship collided with a Spanish Navy vessel in the Gulf of Mexico. Consequently, Morris commanded a squadron of ships in the Gulf to ensure that American merchant commerce in the area would continue unmolested.[74][77][Note 4]

Congress arrived in the Gulf of Mexico in December 1816 and made patrols through July 1817 performing duties that Morris described as "tedious and uninteresting".[77] From there she sailed for Haiti where Morris and an agent of the United States negotiated a settlement with Henri Christophe over the case of a captured vessel. Afterward, Congress sailed for Venezuela to observe and gather information regarding the ongoing Venezuelan War of Independence. She arrived about 21 August and visited the Venezuelan city of Barcelona soon after.[78]

Upon return to the Norfolk Navy Yard later the same year, Morris requested relief as commander due to failing health and Arthur Sinclair assumed command.[79][80][Note 5] Sinclair began preparing for a return voyage to South America carrying a diplomatic contingent to assure various South American countries of the United States' intention to remain neutral in their conflicts with Spain for independence.[82] The diplomats included Caesar A. Rodney, John Graham, Theodorick Bland, Henry Brackenridge, William Reed, and Thomas Rodney.[83] Congress departed on 4 December and returned to Norfolk in July 1818.[84][85]

Early in 1819 Congress made a voyage under the command of Captain John D. Henley to China, becoming the first U.S. warship to visit that country. She returned to the United States in May 1821.[86] Shortly afterward, pirates in the West Indies began seizing American merchant ships and in early 1822, she served as the flagship of Commodore James Biddle. She is recorded as collecting prisoners from the captured pirate ship Bandara D'Sangare on 24 July of that year.[87][88] Her next recorded activity is returning to Norfolk in April 1823 where Biddle immediately prepared for a voyage to Spain and Argentina to deliver the newly appointed Ministers, Hugh Nelson and Caesar A. Rodney respectively.[89][90]

Extensive modifications were required to the berth deck of Congress in order to accommodate Rodney's wife and eleven children.[91] Additionally, Rodney's household goods and furniture, described by Biddle as "enough to fill a large merchant ship," were loaded into her hold that required much of the ships stores to be relocated.[92] She departed from Wilmington, Delaware on 8 June and arrived at Gibraltar where Hugh Nelson disembarked for Spain.[90] On 18 September Congress arrived at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where Rodney hired his own merchant ship to carry his family the rest of the distance to Buenos Aires.[90][93] Congress subsequently returned to Norfolk on 17 December.[94]

After her return, Congress served as a receiving ship; being moved between the Norfolk and Washington Navy Yards under tow as needed. She remained on this duty for the next ten years until a survey of her condition was performed in 1834, and found unfit for repair, she was broken up the same year.[1][95]

Notes

- ^ a b Chapelle states Congress and Constellation were re-rated to 38s during construction by Humphreys because of their large dimensions.[4] Canney references Chapelle when rating Congress a 38-gun frigate, but also questions "... exactly what Humphreys had in mind with rating these ships as 44- or 36-gun frigates when the number of ports certainly did not correspond to the rating and, in fact, the ships rarely carried their rated batteries, reflecting contemporary European practice."[17] Beach states that Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert re-rated Congress and Constellation to 38s once he compared the dimensions of the two ships with the recently completed Chesapeake, which had been reduced in size from a 44 to the extent that she was smaller.[5]

- ^ The Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships article states that on 29 August 1800, Congress recaptured, from a French privateer, the American merchant ship Experiment.[1] However, no other source used for this article contains any mention of the incident; most notably the autobiography of Charles Morris who was a midshipman in Congress during the war.[30]

- ^ Sources do not specifically record Congress's activities between 25 October 1804 and early July 1805. They do however, imply that a number of ships spent the winter months of 1804–1805 undergoing repairs and resupply at Malta.

- ^ The acquisition of Fort Astoria was completed by James Biddle in August 1818.[74][76]

- ^ Morris did not record the date of Congress's return from Venezuela nor the date of his request to be relieved of command.[81]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Congress". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 48.

- ^ a b Allen (1909), p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f Chapelle (1949), p. 128.

- ^ a b c Beach (1986), p. 32.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Beach (1986), p. 29.

- ^ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 350 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 49–53.

- ^ Beach (1986), pp. 29–30, 33.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 42–45.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 61.

- ^ "The Reestablishment of the Navy, 1787–1801: Historical Overview of the Federalist Navy". Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ An Act to provide a Naval Armament. 1 Stat. 351 (1794). Library of Congress. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 56.

- ^ a b c Canney (2001), p. 45.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 53.

- ^ Jennings (1966), pp. 17–19.

- ^ "Essex". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 136.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 133.

- ^ Allen (1909), pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Maclay and Smith (1898) Volume 1, p. 191.

- ^ a b Allen (1909), p. 153.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 139.

- ^ Morris (1880), p. 120.

- ^ Morris (1880), p. 121.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 120–124.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 221.

- ^ Allen (1909), p. 255.

- ^ a b Allen (1909), p. 258.

- ^ "United States". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "New York". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 88, 90.

- ^ a b Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 228.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 92.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 173.

- ^ a b Allen (1905), p. 199.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 224–227.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 252.

- ^ a b Allen (1905), p. 219, 220.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 220.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 268.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 221, 222.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 269.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 282.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 72, 73.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 322.

- ^ Cooper (1856), pp. 244, 245.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 73, 74.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 74, 76.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 77.

- ^ a b Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 325.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), p. 78.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 247.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 106, 107.

- ^ Toll (2006), pp. 419, 420.

- ^ Roosevelt (1883), pp. 174, 175.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 1, p. 521.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, p. 6.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 281.

- ^ Morris (1880), p. 181.

- ^ Allen (1905), pp. 292–293.

- ^ a b Allen (1905), p. 293.

- ^ a b Morris (1880), p. 182.

- ^ "Independence". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, p. 20.

- ^ Allen (1905), p. 294.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b c Cooper (1856), p. 446.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b Scholefield and Howay (1914), p. 432.

- ^ a b Morris (1880), p. 184.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 185–190.

- ^ Morris (1880), pp. 190–191.

- ^ "Sinclair". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Morris (1880), p. 191.

- ^ Brackenridge (1820), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Brackenridge (1820), p. 78.

- ^ Brackenridge (1820), p. 79.

- ^ Read (1870), pp. 238, 241.

- ^ Raymond (1851), p. 47.

- ^ Cooper (1856), p. 448.

- ^ Maclay and Smith (1898), Volume 2, p. 28.

- ^ Wainwright (1951), p. 171.

- ^ a b c Read (1870), p. 241.

- ^ Wainwright (1951), p. 180.

- ^ Wainwright (1951), pp. 179, 180.

- ^ Wainwright (1951), p. 182.

- ^ Wainwright (1951), p. 183.

- ^ Toll (2006), p. 474.

Bibliography

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1905). Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs. Boston, New York and Chicago: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 2618279.

- Allen, Gardner Weld (1909). Our Naval War With France. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1202325.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Beach, Edward L. (1986). The United States Navy 200 Years. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 978-0-03-044711-2. OCLC 12104038.

- Brackenridge, H. M. (1820). Voyage to South America, performed by order of the American Government in the years 1817 and 1818, in the frigate Congress. Vol. I. London: T. and J. Allman. OCLC 1995192.

- Canney, Donald L. (2001). Sailing warships of the US Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-990-5. OCLC 49323919.

- Chapelle, Howard Irving (1949). The History of the American Sailing Navy; the Ships and Their Development. New York: Norton. OCLC 1471717.

- Cooper, James Fenimore (1856). History of the Navy of the United States of America. New York: Stringer & Townsend. OCLC 197401914.

- Jennings, John (1966). Tattered Ensign The Story of America's Most Famous Fighting Frigate, U.S.S. Constitution. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. OCLC 1291484.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton; Smith, Roy Campbell (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. Vol. 1 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1898) [1893]. A History of the United States Navy, from 1775 to 1898. Vol. 2 (New ed.). New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 609036.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Morris, Charles (1880). Soley, J. R. (ed.). "The Autobiography of Commodore Charles Morris U.S.N." Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute. VI (12). Annapolis: United States Naval Institute: 111–219. ISSN 0041-798X. OCLC 2496995.

- Raymond, William (1851). Biographical Sketches of the Distinguished Men of Columbia County. Albany: Weed, Parsons. OCLC 3720201.

- Read, William T. (1870). Life and Correspondence of George Read. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. OCLC 2095027.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1883) [1882]. The Naval War of 1812 (3rd ed.). New York: G.P. Putnam's sons. OCLC 133902576.

- Scholefield, E.O.S.; Howay, Frederic William (1914). British Columbia: From the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. I. Vancouver: S.J. Clarke. OCLC 5756128.

- Toll, Ian W. (2006). Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the US Navy. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05847-5. OCLC 70291925.

- Wainwright, Nicholas B. (April 1951). "Voyage of the Frigate Congress, 1823". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 75, no. 2. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pp. 170–188.

External links

- Guide to the Journal of the USS Congress, 1816–1817 MS 22 held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- Guide to the Remarks Made on Board the United States Frigate Congress, 1817 MS 23 held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- Guide to the Journal of the USS Congress, the Citizen, and the Canton, 1816–1820 MS 24 held by Special Collection & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy