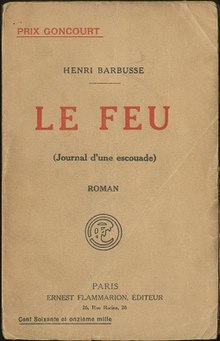

Under Fire (Barbusse novel)

First edition (French) | |

| Author | Henri Barbusse |

|---|---|

| Original title | Le Feu: journal d'une escouade |

| Translator | Robin Buss (2003) |

| Language | French |

| Genre | War Novel |

| Publisher | Ernest Flammarion |

Publication date | December 1916 |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 304 pp |

| ISBN | 1-4264-1576-1 |

Under Fire: The Story of a Squad (French: Le Feu: journal d'une escouade) by Henri Barbusse (December 1916), was one of the first novels about World War I to be published. Although it is fiction, the novel was based on Barbusse's experiences as a French soldier on the Western Front. It was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1916. The novel is described as one of the earliest works of the Lost Generation movement[1] or as the work which started it;[2] the novel had a major impact on the later writers of the movement, namely on Ernest Hemingway[3] and Erich Maria Remarque.[4]

Barbusse wrote Le feu while he was a serving soldier. He claimed to have taken notes for the novel while still in the trenches; after being injured and reassigned from the front, he wrote and published the novel while working at the War Office in 1916.[5]

Summary

[edit]The novel takes the form of journal-like anecdotes which the unnamed narrator claims to be writing to record his time in the war. It follows a squad of French Poilu on the Western front in France after the German invasion. According to Winter, "His intention was to tell the story of a single squad, men from all over France, men of little learning but much generosity of spirit." The anecdotes are episodic, each with a chapter title. The chapter, "Fire" describes a trench assault from the Allied (French) trench across No-Man's Land into the German trench. Barbusse wrote, "Fully conscious of what they are doing, fully fit and in good health, they have massed there to throw themselves once more into that madman's role that is imposed on each of them by the folly of the human race."[6]

Reception and style

[edit]Winter states, "Under Fire was a phenomenal success. The first in the line of such moral witnesses in the twentieth century were soldier-poets and novelists of the Great War. And the first among them was Henri Barbusse." The work was first published in serial form in L'Oeuvre, which enabled Barbusse to bypass the censors. Jacques Bertillon wrote to Barbusse in praise, "It is a masterpiece. It is a document which will remain as a witness [témoin] to this war...."[6]

Like many war novels, Under Fire was criticised for fictionalizing details of the war. In 1929, Jean Norton Cru, who was commissioned to critique French literature of World War I, called Under Fire "a concoction of truth, half-truth, and total falsehood."[7]

The novel was first published in French in December 1916. It was translated into English by William Fitzwater Wray and published in June 1917 by J. M. Dent & Sons. In 2003, Penguin Press published a new translation by Robin Buss with an introduction by the American historian Jay Winter.[5]

In Robert Graves' autobiography "Good-Bye to All That" he mentions that, during the war, British pacifists urged Siegfried Sassoon to write "something red-hot in the style of Barbusse's "Under Fire" but he couldn't do it."[8]

Book sales were used to create the ARAC (Association Républicaine des Anciens Combattants).[6]: xi

The novel had a major impact on the later writers of the movement, namely on Ernest Hemingway. In 1942, he wrote that he was influenced by its style:

The only good war book to come out during the last war was Under Fire by Henri Barbusse. He was the first to show us, the boys who went from school or college to the last war, that you could protest in anything besides poetry, the gigantic useless slaughter and lack of even elemental intelligence in generalship that characterized the Allied conduct of that war from 1915 to 1917... But when you came to read it over to try to take something permanent and representative from it the book did not stand up. Its greatest quality was his courage in writing it when he did... [Barbusse] had learned to tell the truth without screaming.[3]

Barbusse's main features were rejection of aestheticism in favor of realism with a new form of protest and social criticism, suspending protest in poetry and a method which Hemingway called "constater". The influence of Barbusse's style on Hemingway is seen in A Farewell to Arms.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (16 December 2013). The European Powers in the First World War. Routledge. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-135-50694-0.

- ^ Doughboys on the Great War: How American Soldiers Viewed Their Military Experience. University Press of Kansas. 20 January 2017. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7006-2444-7.

- ^ a b c War in Ernest Hemingway's a Farewell to Arms. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. 14 March 2014. ISBN 978-0-7377-7069-8.

- ^ Tate, Trudi (2009). "The First World War: British Writing". In McLoughlin, Catherine Mary (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to War Writing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 160–174. ISBN 978-0-521-89568-2.

- ^ a b Barbusse, Henri (2003) [1916]. Under Fire. Penguin Classics (in French). Winter, Jay (introduction). New York: Penguin Books.

- ^ a b c Barbusse, Henri (2004). Under Fire. New York: Penguin Books. pp. ix, x, 204–253. ISBN 9780143039044.

- ^ Cru, Jean Norton (1929). Témoins; essai d'analyse et critique des souvenirs de combattants édités en français de 1915 à 1928 (in French). Paris: Les Étincelles.

- ^ Graves, Robert (1998). Good-bye To All That. New York: Vintage International. p. 258. ISBN 9780385093309.

External links

[edit]- Under Fire, scanned books from Internet Archive, Google Books and Project Gutenberg

- Under Fire:the story of a squad, English translation by Fitzwater Wray at Project Gutenberg

- Under Fire, HTML edition

Under Fire public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Under Fire public domain audiobook at LibriVox