User:Ana Swanson KSU/sandbox

Efforts to further combat the high rate of femicide in Honduras were seen in 2018 with the creation of the Inter-Agency Commission to Monitor Investigations into Violent Deaths of Women and Femicide, which was created following the country’s establishment of the Ministry of Human Rights in 2017. [1]

More recent data reports that the level of impunity for femicides continues to be high, as it reached 95% for the 338 cases that occurred during 2017 through early 2018.[2]

Violence Against Women in Honduras (GBV)

[edit]In the country of Honduras, violence against women in the form of femicide, domestic violence, sexual violence, and overall gender-based violence is a prevalent problem.[3] This serious issue has resulted in over 5,000 violent deaths of Honduran women between 2003 - 2016.[4] More recent data notes that there were over 15,000 reports of sexual violence between 2010-2014, which equates to roughly the violent death of a women every 16 hours and one report of sexual violence by a woman every hour.[5] The rate of violence against women in Honduras has risen during the Covid-19 pandemic due to the confinement of women and children to their homes. This has created an environment of increased risk of violence as it has limited Honduran women's ability to seek help or flee, resulting in over 40,000 cases of violence against women during the months of January - May 2020.[6]

The topic of violence against women did not gain visibility in Honduras until the early 1990s, thanks in part to work done by women's social groups and feminists to illuminate crimes committed against women and seek institutional change to better protect this segment of the population.[7] Although this issue has gained more attention, women in Honduras who have been victims of sexual violence and/or femicide face a 95% impunity rate. This has created an environment in which Honduran women face great challenges to gaining justice against their aggressor.[8]

Types of Gender-Based Violence

[edit]According to the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women (Convención Interamericana para Prevenir, Sancionar y Erradicar la Violencia contra la Mujer), violence against women is defined as, "whatever action or conduct, that is based on gender, which causes death, harm, or physical, sexual, or psychological harm to a woman, in both public and private spaces."[7] In regard to Honduras, the most noted forms of gender-based violence include domestic violence, sexual violence, femicide, and human trafficking. The government has made efforts to prevent these crimes through services offered at its Women's Offices that are present in all 289 municipalities. [8]

Domestic and Sexual Violence

[edit]The most noted form of sexual violence in the country is rape, which ranks as the third most prevalent crime in the country. In many cases, women do not report the crime to the police due to the lack of justice and support from government institutions tasked with dealing with these crimes. Data from 2015 reports that there were over 3,000 complaints of sexual violence.[8] The United Nations Development program reported that in 2019, 9 out of 10 victims of sexual offenses in Honduras were women.[9] Additionally, seeking help for unwanted pregnancies after experiencing sexual violence, including rape, is currently illegal under the Honduran government. Honduras is currently the only Latin American country in which emergency contraception is illegal in all situations.[10]

The majority of domestic abuse complaints are filed by Honduran women, which averaged around 20,000 complaints per year between 2009 - 2012.[8] The prevalence of this crime has increased by 390% between 2008 - 2015.[11] The rate of domestic violence has continued to increase during the Covid-19 pandemic. As reported by the National Observatory of Violence, the rate of domestic violence in Honduras has risen by 4.1% since the start of the pandemic.[12]

Femicide

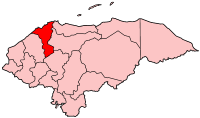

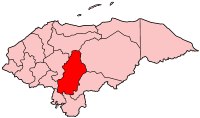

[edit]Compared to other countries around the world, Honduras holds some of the highest rates of violent female deaths. The average number of femicides per month in Honduras in 2019 was 32; nearly three times the world average.[9] For Honduran women that are of childbearing age, femicide has been reported as the second common leading death for women in the country.[13] The most recent data available in late 2020 reports 240 femicides, over half of which took place after the initiation of lockdown measures implemented by the Honduran government.[12] In regard to data from 2019, most femicides occurred in the Northern and Central region of the country, particularly in San Pedro Sula and Distrito Central.[9]

Human Trafficking

[edit]As noted by the U.S. Department of State in their Trafficking in Persons Report for 2020, women are one of the primary targets for trafficking in Honduras.[14] Victims of human trafficking, specifically those who are victims of commercial sexual exploitation, are overwhelmingly women (71% in 2010).[8] Women victims of human trafficking are additionally vulnerable to being exploited for labor and being used as transporters of drugs, both in Honduras and abroad.[15] Similar to the high rate of impunity for perpetrators of sexual violence and/or femicide, the rate of impunity for human traffickers is also alarmingly high, reaching 100% in 2015.[8]

To combat this problem, the Honduran government created the Inter-Institutional Commission to Combat Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking in Persons (CICESCT) in 2012. The primary function of this agency is to combat the issue, as well as serve as a resource center for victims to connect them with specialized services (such as lawyers and healthcare professionals).[15] More recent efforts to combat trafficking include the establishment in 2018 of the anti-trafficking unit under the Attorney General.[14]

Legislation

[edit]| Year | Domestic Legislation |

|---|---|

| 1982 | National Constitution[16]

Prohibits gender-based discrimination and declares equal rights for both men and women. |

| 1997 | Law on Domestic Violence[17] |

| 2006

(amended in 2013) |

Reformed Law on Violence Against Women[11] |

| 2006 | Domestic Violence Act[8] |

| 2000 | Law of Equal Opportunities for Women[16] |

| 2013 | Femicide Law Article 118-A

Under the criminal code, femicide is a crime punishable by 30-40 years in prison.[8] |

| 2012 | Law Against Trafficking in Persons[18] |

International/Regional Conventions

- Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women, also known as Convention of Belém do Pará (1995)[19]

Notable Cases

[edit]Notable cases of femicides in Honduras:

Activism/Protest

[edit]Notable Leaders

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Visit to Honduras Report of the Working Group on the Issue of Discrimination Against Women in Law and in Practice. United Nations General Assembly. 2019. p. 5.

- ^ Honduras Stakeholder Report for the United Nations Universal Periodic Review. Minneapolis: The Advocates for Human Rights. 2019. p. 2.

- ^ https://www.theadvocatesforhumanrights.org/uploads/honduras_cedaw_loi_ahr_january_2016.pdf

- ^ McSheffrey, Elizabeth (March 1, 2018). "Honduran Women Pay for Rights With Their Lives". Canada's National Observer. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Observatorio de Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres" (PDF). Centro de Derechos de Mujeres. July 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rincón, Andrea (June 10, 2020). "En Honduras, una mujer es víctima de agresión física cada hora". France 24. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b https://pdba.georgetown.edu/Security/citizensecurity/honduras/documentos/centro.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h https://www.theadvocatesforhumanrights.org/uploads/honduras_iccpr_loi_july_2016.pdf

- ^ a b c d "Infografía: Análisis de violencia contra las mujeres en Honduras 2019". United Nations Development Program. November 21, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Filipovic, Jill (June 7, 2019). "'I Can No Longer Continue to Live Here'". Politico Magazine. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b https://www.theadvocatesforhumanrights.org/uploads/honduras_upr.pdf

- ^ a b "Let's Talk about It: Violence against Women in Honduras". Education Development Center. November 23, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Neither-Security-nor-Justice_SGBV-Gang-Report-FINAL_0.pdf

- ^ a b "2020 Trafficking in Persons Report: Honduras". U.S. Department of State. 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b https://uprdoc.ohchr.org/uprweb/downloadfile.aspx?filename=7817&file=EnglishTranslation

- ^ a b c Menjívar, Cecilia (August 2017). "The Architecture of Feminicide: The State, Inequalities, and Everyday Gender Violence in Honduras". Latin American Research Review.

- ^ "Law on Domestic Violence". evaw-global-database.unwomen.org. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "National Campaign Against Human Trafficking Launched in Honduras - Honduras". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ^ "INTER-AMERICAN CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION, PUNISHMENT AND ERADICATION OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN "CONVENTION OF BELEM DO PARA"". www.oas.org. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Case History: Gladys Lanza Ochoa". Front Line Defenders. 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "From Survivors to Defenders: Women Confronting Violence in Mexico, Honduras & Guatemala" (PDF). Retrieved February 27, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

| This is a user sandbox of Ana Swanson KSU. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |