User:AustinJAragon/British Raj railway section

Railways[edit]

British India built a modern railway system in the late 19th century, which was the fourth largest in the world. At first the railways were privately owned and operated. They were run by British administrators, engineers and craftsmen. At first, only the unskilled workers were Indians.[1]

The East India Company (and later the colonial government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to 5% during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99-year lease, with the government having the option to buy them earlier.[2] Two new railway companies, the Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR) and the East Indian Railway Company (EIR) began to construct and operate lines near Bombay and Calcutta in 1853–54. The first passenger railway line in North India, between Allahabad and Kanpur, opened in 1859. Eventually, five British companies came to own all railway business in India,[3] and operated under a profit maximization scheme.[4] Further, there was no government regulation of these companies.[5]

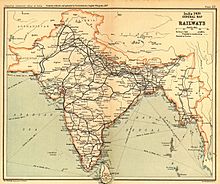

In 1854, Governor-General Lord Dalhousie formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions of India. Encouraged by the government guarantees, investment flowed in and a series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion of the rail system in India.[6] Soon several large princely states built their own rail systems and the network spread to the regions that became the modern-day states of Assam, Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh. The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 kilometres (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 kilometres (15,842 mi) in 1880, mostly radiating inland from the three major port cities of Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.[7]

After the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, and subsequent Crown rule over India, the railways were seen as a strategic defense of the European population, allowing the military to move quickly to subdue native unrest and protect Britons.[8] The railway thus served as a tool of the colonial government to control India as they were "an essential strategic, defensive, subjugators and administrative 'tool'" for the Imperial Project.[9]

Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies supervised by British engineers.[10] The system was heavily built, using a broad gauge, sturdy tracks and strong bridges. By 1900 India had a full range of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks. In 1900, the government took over the GIPR network, while the company continued to manage it.[10] During the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and grain to the ports of Bombay and Karachi en route to Britain, Mesopotamia, and East Africa. With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to making artillery; some locomotives and cars were shipped to the Middle East. The railways could barely keep up with the increased demand.[11] By the end of the war, the railways had deteriorated for lack of maintenance and were not profitable. In 1923, both GIPR and EIR were nationalised.[12][13]

Headrick shows that until the 1930s, both the Raj lines and the private companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers, and even operating personnel, such as locomotive engineers. The hard physical labor was left to the Indians. The colonial government was chiefly concerned with the welfare of European workers, and any Indian deaths were "either ignored or merely mentioned as a cold statistical figure."[14][15] The government's Stores Policy required that bids on railway contracts be made to the India Office in London, shutting out most Indian firms.[13] The railway companies purchased most of their hardware and parts in Britain. There were railway maintenance workshops in India, but they were rarely allowed to manufacture or repair locomotives. TISCO steel could not obtain orders for rails until the war emergency.[16]

The Second World War severely crippled the railways as rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were converted into munitions workshops.[17] After independence in 1947, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated to form a single nationalised unit named the Indian Railways.

India provides an example of the British Empire pouring its money and expertise into a very well-built system designed for military purposes (after the Mutiny of 1857), in the hope that it would stimulate industry. The system was overbuilt and too expensive for the small amount of freight traffic it carried. Christensen (1996), who looked at colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service, and private-versus-public interests, concluded that making the railways a creature of the state hindered success because railway expenses had to go through the same time-consuming and political budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not be tailored to the current needs of the railways or of their passengers.[18]

- ^ I. D. Derbyshire (1987). "Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860–1914". Modern Asian Studies. 21 (3): 521–45. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00009197. JSTOR 312641.

- ^ R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-81-230-1254-4.

- ^ Laxman D. Satya, "British Imperial Railways in Nineteenth Century South Asia," Economic and Political Weekly 43, No. 47 (November 2008): 72.

- ^ Dharma Kumar and Meghnad Desai, The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, c.1757-c.1970 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 751.

- ^ Satya, 72.

- ^ Thorner, Daniel (2005). "The pattern of railway development in India". In Kerr, Ian J. (ed.). Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 80–96. ISBN 978-0-19-567292-3.

- ^ Hurd, John (2005). "Railways". In Kerr, Ian J. (ed.). Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–172–96. ISBN 978-0-19-567292-3.

- ^ Barbara D Metcalf and Thomas R Metcalf, A Concise History of India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 96.

- ^ Ian Derbyshire, 'The Building of India's Railways: The Application of Western Technology in the Colonial Periphery, 1850-1920', in Technology and the Raj: Western Technology and Technical Transfers to India 1700-1947 ed, Roy Macleod and Deepak Kumar (London: Sage, 1995), 203.

- ^ a b "History of Indian Railways". Irfca.org. IRFCA. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Headrick 1988, p. 78–79.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 690.

- ^ a b Khan, Shaheed (18 April 2002). "The great Indian Railway bazaar". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 July 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Satya, 73.

- ^ Derbyshire, 157-67.

- ^ Headrick 1988, p. 81–82, 291.

- ^ Wainwright, A. Marin (1994). Inheritance of Empire. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-275-94733-0.

- ^ Christensen, R. O. (September 1981). "The State and Indian Railway Performance, 1870–1920: Part I, Financial Efficiency and Standards of Service". The Journal of Transport History. 2 (2): 1–15. doi:10.1177/002252668100200201. S2CID 168461253.