User:Caeciliusinhorto/Sappho images

| This page in a nutshell: Many ancient images which have been identified as depicting "Sappho" do so on the basis of little evidence. Only four vases, a few coins, and a mosaic can be securely identified on the basis of inscriptional evidence; no ancient sculpture can be securely identified as Sappho. When choosing an image to depict Sappho in Wikipedia articles, use caution and add appropriate caveats to the caption. |

The various ancient images of Sappho are a perennial topic for discussion on Talk:Sappho. Previous discussions can be found at:

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 3#The picture

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 4#Pictures

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 4#The picture yet again

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 6#Palazzo Massimo bust of Sappho

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 6#Image

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 6#Delete current main picture?

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 6#Another image

- Talk:Sappho/Archive 7#lede picture

This page aims to summarise what ancient images exist which depict (or may depict, or have been thought to depict) Sappho, and the reasons for believing (or disbelieving) those claims. The general principle is: be skeptical. Historical identifications of ancient artworks often proposed that they represented particular individuals even when the evidence supporting that claim was weak. Identifications of ancient artworks given on Wikimedia Commons are often not cited to any reliable source, and do not necessarily agree with the consensus of modern scholarship.

While the examples given on this page are all about images of Sappho, many of the principles hold for ancient depictions of other figures. If the individual depicted isn't identified by an inscription, or some other exceptionally clear evidence, we should generally be cautious in saying an image is "of" them!

Vases[edit]

The earliest depictions of Sappho come from Athenian vase-painting. Four vases are securely identifiable as Sappho on the basis of their inscriptions. Three are red-figure vases; the fourth uses Six's technique. Three of these are illustrated on Commons. A fifth vase has an inscription identifying it as being of Sappho; the vase is now lost and the inscription has been doubted. A line drawing is on Commons.

1. The kalpis by the Sappho Painter, in the collection of the National Museum of Warsaw, showing Sappho with a lyre. Inscribed "ΦΣΑΦΟ". c.510 BC, the earliest surviving depiction of Sappho.[1] Commons has both a high-quality photograph and a line-drawing.

-

Licensing is weird - I think probably this is okay but was mislicensed when uploaded!

-

Diagram from DM Robinson's Sappho and her Influence

2. The Brygos Painter's kalanthos, in the collection of the Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich, showing Sappho alongside Alcaeus. Inscription reads "ΣΑΦΟ". c.480-70 BC. Alternatively Martin Robertson suggests that it is the work of the Dokimasia Painter, BP's pupil.[1] This is perhaps the most famous and recognisable of the vases, and there is a good line drawing on Commons. The photographs aren't as high-quality as for the Sappho Painter's kalpis, and the inscriptions are not legible.

-

Fairly clear drawing showing both Sappho and Alcaeus, and making the inscriptions clear

-

Not the best detail, but the inscription identifying Sappho is (barely!) visible

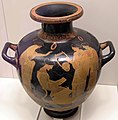

3. The hydria by the group of Polygnotos, in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, showing Sappho seated alongside three standing women. Inscribed "ΣΑΠΠΩΣ".[1] Like the Brygos Painter's vase, the photographs are good enough to see clearly but not excellent. Since the vase was first published in the 19th century, the inscription is no longer visible.[2] Unlike the Brygos and Sappho Painters' vases, no line-drawing has yet been uploaded to Commons. Text on the book-roll Sappho holds is visible, though its content is disputed; Edmonds included it as fr. 1a in his 1922 Loeb, but modern editors have largely not accepted it as an authentic Sappho fragment.

-

Detail simply cropped from the original image

4. A Kalyx-Krater by the Tithonos Painter, in the collection of the Van der Heydt Museum in Wuppertal, showing Sappho with a lyre. Inscription reads: "ΣΑΦΦΟ".[1] No photos on Commons. Black and white photos on Oxford University's Classical Art Research Centre website.

5. A fifth vase, a now lost bell-krater, formerly of the Middleton Collection, is identified as Sappho with an inscription. However Beazley (Greek Vases in Poland 1928) doubted the inscription, and Yatromanolakis says that "the authenticity in this case cannot be verified or rejected unless the vase is recovered".[3] A line drawing is on commons.

There are also several Attic vases which are not inscribed with Sappho's name, but have been identified as Sappho on the basis of similarities to the known vases. Yatromanolakis (2001) cites three: a belly-amphora in Stuttgart, possibly by the Andokides Painter; a lekythos in Hamburg, attributed to the Diosphos Painter, and a kylix in the Louvre, by the Hesiod Painter. See Yatromanolakis (2008), Sappho in the Making: The Early Reception for arguments against the validity of this practice. Other vases of this type illustrated on Commons include a red-figure hydria in the British Museum which is similar to the NAMA hydria (the BM describes the identification with Sappho as "ambiguous"[4]), and an amphora by the Niobid Painter in the Walters Art Museum showing a seated woman with a barbiton, alongside two other women (the museum describes it as "a musical scene" and does not mention Sappho[5]). We should probably avoid these where trying to depict Sappho; the Sappho Painter, Brygos Painter, and Group of Polygnotos vases are sufficient for this.

-

Detail of British Museum hydria. High resolution, but unfortunate glare on the head.

-

Niobid Painter amphora

-

Detail of Niobid Painter amphora. Cropped from larger image so relatively small.

-

Yatromanolakis 2001 (n.16) cites Kaufman-Sanara 1997 arguing that this kylix from the Louvre depicts Sappho; the Louvre's online catalogue describes it as depicting a Muse.[6]

Sculpture[edit]

Ancient sculptural depictions of Sappho are less easy. Known ancient sculptures of Sappho include: bronze by Silanion at Syracuse (Cicero, In Verrem II), sculpture at Pergamon (epigram by Antipater), and seated statue at Zeuxippos in Constantinople (Christodoros, Greek Anthology).

No surviving sculpture has been generally accepted as an ancient representation of Sappho.[7] According to Gisela Richter: "a number of tentative identifications have been made of sculptured heads ... there is only a vague possibility ... that they represent Sappho".[8] If showing images of an ancient sculpture which may represent Sappho, be careful to make the source of the attribution clear.

Surviving sculptures which have sometimes been identified as depicting Sappho include:

Melian plaque[edit]

A terracotta votive plaque in the British Museum showing a seated woman with a lyre and a standing man. The museum describes it as "perhaps" depicting Sappho and Alcaeus.[9] According to Gisela Richter, it is "now thought to represent an every-day scene".[8]

Capitoline bust[edit]

An ancient bust of a woman with the inscription Σαπφω Ερεσια ("Sappho of Eresos") from the Capitoline Museum. The inscription is not ancient: possibly the work of Pirro Ligorio in the 1500s.[10][11]

Munich head[edit]

A head in the Glyptotek in Munich described on Commons as "probably" a copy of Silanion's Sappho. This type is judged the most plausible sculpture identified as Sappho by Évelyne Prioux in her recent survey of ancient depictions of female poets.[12] The Glyptothek head was one of three related heads identified by Eduard Schmidt as Silanion's Sappho, along with heads in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg, and the Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna.[13] Richter associates the Liechtenstein Museum head (perhaps this?) with several others including one in the Ostia Museum (inv.463), and says that it has "conclusively been shown to represent Hygeia".[7] The Ostia Museum online calls the work "perhaps Hygeia", and it is listed on Arachne as "Frau oder Apollon ?" ("woman or Apollo?").[14] A sculpture of this type from Byblos is identifiable as Hygeia by the snake it holds, but it has been suggested that the statue type originally represented Sappho and the Hygeia was a re-working.[15]

This may be the sculpture listed in Dieter Ohly's Glyptothek München: griechische und römische Skulpturen as being "vermutlich nach einer Statue der Sappho von Silanion" ("probably after a statue of Sappho by Silanion"),[16] and by Fürtwangler and Wolters as being a head of Artemis by Praxiteles.[17]

A head in Antalya, Turkey, which recieved press coverage in 2020 as having been newly identified as Sappho appears to be of this type.[18]

Naples bust[edit]

A bronze bust in the National Archaeological Museum Naples is described as the "so-called" Sappho. Cornell library, which owns a cast of the bust, describes the identification as "highly speculative"[19]) and Gisella Richter notes the identification is "without helpful evidence".[7]

Met head[edit]

A marble head in the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York is listed in the Museum's online catalogue as depicting "Sappho?".[20] Many versions of this head are known, so it must have been a famous work in antiquity.[7] Richter groups this head with versions in the Galleria Geografica, Vatican; Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna; Museo Biscari, Catania; Prado, Madrid; Museo Arceologico, Florence; and Ashmolean, Oxford.

A catalogue note for a marble head in a 2014 Sotheby's sale associates this type with the "fine head with a fillet wound several times round the hair" that Richter describes as "commonly recognized as representing Aphrodite".[7][21] A similar head is in the British Museum, which describes it as "possibly Sappho".[22]

Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme head[edit]

Black basalt head from the Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme. Several images on commons, where it is variously identified as "Sappho", "Sappho?" and "cosiddetta Saffo" ['so-called Sappho']. Apparently modern but based on an ancient original. World History Encyclopedia describes it as a modern "replica or even re-working" of an ancient original;[23] Alamy and Getty both list it as a modern copy of a Greek original;[24] and in the lot description of a Christies' auction in 2020 it is cited as a modern bust.[25] Looks to be related to the Met head – compare the tie at the top of the head, and the side view with that given as fig. 258 in Richter, Portraits of the Greeks.

Sappho/Olympias type[edit]

Head traditionally called the "Sappho" type but commonly believed to represent Aphrodite.[26] A head of this type in the British Museum is viewable in their online collection catalogue.[27] Davison, Lundgreen, and Waywell 2009 list 21 heads of this type.[28]

-

Chiaramonti head

-

Istanbul head

Davanzati bronze[edit]

Supposedly identified by Goffredo Bendinelli as a fourth century BC portrait of Sappho in Ausonia 1911. Formerly of the Davanzati Palace, Florence.[29] Tracking down more information is proving difficult.

Neues Museum double head[edit]

Honourable mention goes to a bust in the Neues Museum Berlin previously described on Commons as being a double portrait of Sappho and Alcaeus. Listed on Arachne as being of an unidentified man and woman.[30]

Other[edit]

Ancient depictions securely identifiable as Sappho exist on Lesbian coins from both Eresos and Mytilene,[31] a Roman-era mosaic from Sparta,[32] and a stucco relief in the Porta Maggiore Basilica which is "now generally accepted" as depicting Sappho's leap from the Leucadian rock.[33] Two now-lost gems are also identifiable as representing Sappho from inscriptions.[34]

An ancient painting of Sappho by Leon is mentioned by Pliny. An epigram by Demochares in the Greek anthology describes a painting of Sappho which may be the same one mentioned by Pliny,[35] or may be a purely poetic exercise, not based on any real portrait.[36] These paintings are lost. A well-known fresco in Pompeii famously does not depict Sappho.

A mosaic from the tomb of T. Aurelius Aurelianus shows a herm which has sometimes been identified as Sappho, including on Commons. The mosaic does not include any inscription that would associate the herm with Sappho, and other identifications have been proposed, including Dionysius, Apollo, and the boy's teacher.[37] Prioux identifies the herm as Sappho, and notes its resemblance to the Sappho depicted in the Sparta mosaic.[38]

-

Roman-era Spartan mosaic inscribed Σαφφω

-

Coin in the British Museum, inscribed ΨΣΑΠΦΩ.[39]

-

Drawing of a Mytilenean coin with a head, supposedly Sappho, on the obverse, and a lyre on the reverse.[40]

-

Sappho's leap from the Porta Maggiore Basilica relief.

-

This Pompeiian fresco definitely does not depict Sappho

-

Various possible identifications. Unmentioned by Richter.

Appendix: Ancient images of other female poets[edit]

Tatian lists sculptures of all nine of Antipater of Thessalonica's canon of women poets in his Address to the Greeks.[41] Pausanias mentions a monument (probably a statue) dedicated to Corinna in Tanagra, and a painting of her in the civic gymnasium. In Argos, he reports a stele of Telesilla holding a helmet in her hand.

The Compiegne museum sculpture of Corinna is identified by an inscription; it may be a copy of Silanion's sculpture of her. Some (e.g. West) dispute this (not least because it interferes with their late dating of Corinna!) Various paintings of a man and a woman wearing wreaths from Pompeii are conventionally identified as Corinna.

The "Maiden of Antium" has been suggested as based on Lysippos' Praxilla by Arvanitopoulos (1909);[42] as has a head from the Palazzo Pitti (illus. Gardner 1918 fig.6).[42] The "Berlin Dancer" has also been suggested by e.g. Stewart 1990.[43] A red-figure cup showing a symposium scene is inscribed with four words from a scholion by Praxilla.[44]

A bronze figure usually identified as Artemis has been suggested as representing Telesilla.[45]

-

Compiegne Corinna

-

"Maiden of Antium". Arvanitopoulos suggested that this was based on Lysippos' Praxilla

-

Berlin Dancer, another possibility for Praxilla

-

Bronze Artemis from the Piraeus, identified by Semni Karouzou as Telesilla

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Évelyne Prioux, "Les Portraits de poétesses, du IVe siecle avant J.-C. à l'époque impériale", Féminités Hellénistiques: Voix, Genre, Représentations eds. C. Cusset, P. Belenfant, C.-E. Nardone 2020

- Gisela M. Richter, Portraits of the Greeks 1965

- Patricia Rosenmeyer, "From Syracuse to Rome: The Travails of Silanion's Sappho", Transactions of the American Philological Society 2007

- Jane McIntosh Snyder, "Sappho in Attic Vase Painting", Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality, and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology eds. Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, Claire L. Lyons, Natalie Boymel Kampen, 1997

- Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou, "Sappho Illustrated" in Studies in Sappho and Alcaeus 2019

- Dimitrios Yatromanolakis, "Visualising Poetry: An Early Representation of Sappho", Classical Philology 2001

- Dimitrios Yatromanolakis, Sappho in the Making: the Early Reception 2008

Further reading[edit]

- Percy Gardener, "A Female Figure in the Early Style of Pheidias", Journal of Hellenic Studies 1918

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Yatromanolakis, Sappho in the Making, Ch.2

- ^ Tsantsanoglou 2019 p.2

- ^ Yatromanolakis 2001, "Visualizing Poetry: An Early Representation of Sappho" n.15

- ^ British Museum, online catalogue entry

- ^ Walters Art Museum online

- ^ https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010261759

- ^ a b c d e Richter, Portraits of the Greeks, p.72

- ^ a b Richter, Portraits of the Greeks p.71

- ^ British Museum online collection

- ^ Brent Nongbri, "The Capitoline Sappho"

- ^ Beatrice Palma Venetucci, "Pirro Ligorio and the Rediscovery of Antiquity"

- ^ Prioux 2020

- ^ Thorsen 2012, p.709

- ^ Ostia Museum; Arachne

- ^ Prioux 2020

- ^ Ohly 2001, p.36

- ^ Fürtwangler, Illustrierter Katalog der Glyptothek König Ludwig's I zu München, cat. 249a; Wolters, Führer durch die Glyptothek König Ludwigs I. zu München, cat.476

- ^ Daily Sabah

- ^ Cornell Library

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art, online catalogue entry

- ^ Sotheby's New York, Antiquities, 12 December 2014 lot 29

- ^ British Museum Catalogue online

- ^ World History Encyclopedia, "Sappho of Lesbos, Palazzo Massimo"

- ^ Alamy; Getty

- ^ Christie's, "Maîtres Anciens, Peinture - Sculpture" 15 September 2020. Lot 135.

- ^ Richter Portraits p.72; cf. Furtwangler Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture p.66 n.2

- ^ British Museum Online

- ^ DAVISON, CLAIRE CULLEN, et al. “PHEIDIAS - THE SCULPTURES & ANCIENT SOURCES: VOLUME 1.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, no. 105, 2009, pp. 526ff.

- ^ Illustrated catalogue of the exceedingly rare and valuable art treasures and antiquities formerly contained in the famous Davanzati Palace, Florence, Italy, Cat.80

- ^ Arachne, "Doppelkopf eines unbekannten Mannes und einer unbekannten Frau"; Arachne, "Porträt einer Frau / Doppelkopf eines unbekannten Mannes und einer unbekannten Frau"

- ^ Richter, Portraits p.70; see figs. 253–256 and 259–261 for more examples

- ^ Richter & Smith, Portraits p.196

- ^ D'Alessio 2022, "The Afterlife of Sappho's Afterlife" p.10

- ^ Rosenmeyer, "From Syracuse to Rome: The Travails of Silanion's Sappho" n.32

- ^ Richter Portraits p.70

- ^ Rosenmeyer, "Silanion's Sappho" p.292

- ^ Mihajlovic, "Roman Epigraphic Funeral Markers"

- ^ Prioux, 228

- ^ 2nd Century Mytilenean coin with the head of Sappho (BNK,G.510) in the British Museum

- ^ British Museum online catalogue

- ^ Evans, "Prostitutes in the Portico of Pompey" p.129

- ^ a b FP Johnson, Lysippos 233-4

- ^ Evans, "Prostitutes in the Portico of Pompey" n.14

- ^ Csabo & Miller, "The 'Kottabos-toast' and an Inscribed Red-figure Cup" 1991

- ^ Prioux 2020

![Yatromanolakis 2001 (n.16) cites Kaufman-Sanara 1997 arguing that this kylix from the Louvre depicts Sappho; the Louvre's online catalogue describes it as depicting a Muse.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Muse_kitharai_Louvre_CA482.jpg/115px-Muse_kitharai_Louvre_CA482.jpg)

![Coin in the British Museum, inscribed ΨΣΑΠΦΩ.[39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Sappho_coin_British_Museum.jpg/120px-Sappho_coin_British_Museum.jpg)

![Drawing of a Mytilenean coin with a head, supposedly Sappho, on the obverse, and a lyre on the reverse.[40]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Sappho_coin.png/120px-Sappho_coin.png)