User:Jacqke/Traditional African lutes

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | plucked string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321

3: Instruments in which sound is produced by one or more vibrating strings (chordophones, string instruments). 32: Instruments in which the resonator and string bearer are physically united and can not be separated without destroying the instrument 321: Instruments in which the strings run in a plane parallel to the sound table (lutes) 321.3: Instruments in which the string bearer is a plain handle (handle lutes) 321.33: Instrument in which the handle extends into but does not pass completely through the resonator (tanged lutes) |

| Related instruments | |

See also: Sub-Saharan African music traditions

Early common cultural bonds

[edit]Kingdoms and group associations in West Africa which interconnected cultures included the Mali Empire c. 1235–1670, Sosso Empire c. 1054–c. 1235, Gao Empire c. 7th century–1325, Ghana Empire c. 100–300–c. mid-1200s and Pre-imperial Mali. It was in the Mali Empire that Al-'Umari and Ibn Battūta mentioned the use of lutes.[1]

Later kingdoms inluded the Songhai Empire c. 1430s–1591, Jolof Empire 13-14th century–1549, Kaabu Empire 1537–1867, and Empire of Great Fulo 1512–1776.

Outside cultural influence includes contact with India, Indonesia/Malay culture, Muslim culture and European culture.

North Africa and Maghrib

[edit]Characteristics

[edit]Lutes in Africa may be distinguished geographically, to include West Africa, the Maghreb, and the Rice Coast. They have been grouped by cultures and peoples that play them. They have been grouped by status such as instruments of Griots (a caste of professional musician) and folk instruments. They may be viewed in terms of their structural characteristics and the methods musicians use in playing the instruments.

321.31 spike lutes

[edit]These are lutes in which a handle passes through both side walls of a resonator. Handles tend to be rods or sticks.[1, p7] Among African lutes these are found along the rice coast.

321.32 necked lutes

[edit]Lutes in which the carved neck is attached to the resonator or carved from the resonator.[1, p7] Lutes in this category tend to be in countries bordering on the Mediterranean and with cultural connections to the middle east. Typical examples include the oud. This category also includes Coptic lutes (Egyptian), which have similarities to ancient Egyptian lutes, but also to Greek/Roman pandura and the rubab (Pamiri rubab, Seni rebab). The Coptic lute's neck is hollow, as are the rubabs.

321.33 tanged lutes

[edit]Also called an internal-spike lute. These are instruments like the spike lutes, except that the handle touches only one side of the resonator body, the end remaining inside or poking through the soundboard. These do not piece the resonator body but rest in an indentation in the resonator; those like the Griot lutes are woven in and out through the skin sound table[1, p7] These are the typical lute of West Africa. Some non-Griot lutes have the handle lying on top of the sound table.

West Africa

[edit]Griot lute

[edit]-fan shaped bridge feature of West African griot instruments[charry, p5]

Non-griot lute

[edit]-cylindrical bridge

Rice Coast

[edit]The Rice Coast of Africa is the region on the Atlantic Coast, from Senegal to Liberia. Many of its residents were enslaved because of their knowledge in growing rice.[1] The Rice Coast has lutes that may be closely related to the American banjo.[2]

Spike Lutes

[edit]See also Music of Guinea-Bissau, Balanta people

The spike lutes of the Rice Coast have resonators made from gourds, with handles that poke through the side walls on both sides.[2] The handles or round necks are fretless, made from a papyrus stalk.[2] Typically they have 3 strings (a short drone string as on a banjo, and two melody strings).[2] The strings are attached at the neck with tuning rings and pass over the skin soundtable (tacked across the cut opening in the top of the gourd).[2] The strings pass over an upright bridge that sits directly on top of the soundtable's skin surface.[2]

Gourd resonator bodies are usually round, but a variant called entofer uses an oval or tear-shaped gourd, also described as "bulbous."[2]

| European language adaptions | Names in African languages | Pronunciation | Ethnic connections, regions | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akonting[2] (English transliteration)

ekonting[2] (French transliteration} |

[ə'kɔntiŋ] | folk lute of the Jola people, found in Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau in West Africa |  | |

| bunchundo[2] | folk lute of the Manjak | |||

| kisinta[2]

kusunde[2] |

folk lute of the Balanta[3] | |||

| busunde[2][3] | folk lute of the Papel | |||

| ngopata[2][3] | folk lute of the Bijago, Bijago Islands of Guinea Bissau.[3] |

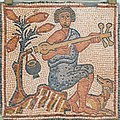

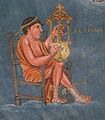

Ancient Egypt

[edit]Lutes after addition of Nubia to Egypt in New Kingdom...Some depictions of lutes and harps in Egypt included the head of a goose, duck, falcon goddess or king on the head of the instrument.[7]

Similarly, trough zither from Africa sometimes include the sculpture of a person. The instrument has a voice, speaks and the sculpture implies it is a person.

-

Lute from Tomb of Nacht, 15th century BC

-

Lute player, tomb of Nakhtamun, TT 341, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna

-

:Egyptian lute, male musician, Rekhmire tt100

-

Painting of a lute player from an ostracon, Deir el-Medina. New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, ca. 1292-1189 BC. Now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 63805

-

Lute player, head of lute has bird head

-

lute has bird head. Nubian

Coptic lutes

[edit]Scholarship

[edit]Lutes have been played parts of Africa for millennia. Historical examples include Ancient Egypt (c. 1850 BC) and the Mali Empire (c. 14th century AD).[1] In spite of the possible history of the instrument there, musical historians have yet to create an extensive history of the lute in Africa.[1] Instead, historians have relied on early musicologists generalizations; Henry Farmer, Curt Sachs and Bernhard Ankermann generalized that African lutes were "are all essentially the same instrument."[1, page 1 and footnote 2] In this view, all lutes could be labeled gunbrī or gunibrī in spite of differences in body style, size and number of strings, in spite of different cultural uses (folk use versus professional Griots), and in spite of different names applied in different languages.[1]

In 1996, musical scholar Eric Charry called attention to a trend toward repudiation, questioning and refining of that assumption.[1] Charry focused on lutes of West Africa, but he noted that study needs to take into account cultures, tribes, regions, design features and history.[1] Cameroon musicologist Francis Bebey included the need to consider an instrument's cultural purpose (to speak or accompany speech rather than singing), language (different pitches in spoken language change meanings of words; musical instruments speak because they can mimic those pitches, songs in African languages are speech completely driven by pitches of words in language).[2] Bebey also brought up a spiritual or religious significance of African instruments: they speak, therefore in some cultures they may be treated with respect as beings.[2]

In 1996 Charry published a list of lutes, divided into similar physical attritutes, by name and culture or tribe.[1] That list was expanded further in 2018 by Shlomo Pestcoe and Greg C. Adams, who were researching the origins of the American banjo.[3]

Another banjo scholar's work that touches on specific African instruments and uncovering their history in the Mediterranean and Americas is Kristina R. Gaddy; Gaddy's research covers blending of African traditions (under European and American slave systems), the instruments' role in African religion as a conduit for spirits to speak, and the conflict between European Christianity and African religions over spiritual-device lutes in the hands of slaves.[4][5]

Chuck Levy interviewed musicians in Africa, revealing how music has changed between generations, how materials in instruments have changed, ritual songs, songs for entertainment, affects of language and dialects on instrument names, and playing techniques.[Banjo Roots, ch5] Nick Bamber explored W African tuning systems in Senegal.[Banjo Roots, ch4]

Bridges

[edit]- Fan shaped [1, p6]

- Cylindrical [1][banjo roots p 223]

- bipedal [banjo roots p 221]

Gallery

[edit]-

kologo

-

lothar

-

ribab

-

Gnawa music

References

[edit]- ^ Opala, Joseph A. "The Gullah: Rice, Slavery, and the Sierra Leone-American Connection". Yale MacMillan Center, Gilder Leherman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

The white plantation owners purchased slaves from various parts of Africa, but they greatly preferred slaves from what they called the "Rice Coast" or "Windward Coast"—the traditional rice-growing region of West Africa, stretching from Senegal down to Sierra Leone and Liberia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Akonting & Other Folk Lutes of West Africa's "Rice Coast"". Shlolomusic.com.

- ^ a b c d Bamber, Nick (1 February 2009). "Two Gourd Lutes from the Bijago Islands of Guinea Bissau". Shlolomusic.com.

- [1] Charry, Eric (March 1996). "Plucked Lutes in West Africa: an Historical Overview". The Galpin Society Journal. 49. The Galpin Society.

- [2] Bebey, Francis (1975). African Music, A People's Art. Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 1-55652-128-6.

- [3] Pestcoe, Shlomo; Adams, Greg C. (2018). "3 List of West African Plucked Spike Lutes". In Winans, Robert B. (ed.). Banjo Roots and Branches. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 45–54.

- [4] Gaddy, Kristina R. (2022). Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo's Hidden History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393866803.

- [5] Kristina R. Gaddy — Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo's Hidden History.

[note: Interview with author Kristina R. Gaddy]

- [6] Ankermann, Bernhard (1901). Die afrikanischen musikinstrumente. Druck von A. Haack. pp. 1–12.

- [7] [1]

- [8] Electronic reference

Catherine Baroin , « The African Odyssey of a Rudimentary Chordophone, the « Lute with an Inner Spike » » , Afrique: Archéologie & Arts [Online], 7 | 2011, published on 01 November 2015 , consulted on 27 August 2024. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/aaa/625 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/aaa.625

- Catherine Baroin, « L’odyssée africaine d’un cordophone rudimentaire, le « luth à pique intérieure » », Afrique : Archéologie & Arts [En ligne], 7 | 2011, mis en ligne le 01 novembre 2015, consulté le 27 août 2024. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/aaa/625 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/aaa.625

- African bluegrass

- Egyptian lute bridge

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Ngoni/Xalam Hypothesis". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "West African Folk & Artisan Lutes". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Origin of West African Lutes". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "From Ancient Egypt to West Africa: The Lute Connection". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The First West African Lutes: Gourd-Bodied?". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "Griot Lutes". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Emergence of the Griot Lutes". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Origin of West African Lutes". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Ngoni/Xalam Hypothesis". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Harp-Lutes of West Africa". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The Early Banjo in the New World". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "Banjo Ancestors Detectives: Daniel Jatta & Ulf Jägfors". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "Introduction On the Trail of the Banjo's Lost Roots: A Personal Journey". Shlolomusic.com.

- Pestcoe, Shlomo (1 February 2009). "The 5-String Banjo". Shlolomusic.com.

https://youtube.com /L6X3q1TetpU