User:Maggie5669/sandbox

The names of Aztec artists are presently unknown to us. The artistic creative activities started prior to the Aztec civilizations which associated with the Totecs. So the aztec artists considered their art to be toltecayo.

In Aztec society, the large number of craftmen worked with the merchants who distuributed their art works to the middle class society. Most of the artists worked on commission orgnized in guilds. The Aztec rulres had controls over the military aristocracy to aquire luxury insignia to reward meritorious services.

This devotional statue of the god Xiuhtecuhtli is depicted as a vigorous youth.Xiuhtecuhtli, the solar diety, "Turquoise Lord", also associated with the power of the deified Mexico-Aztec hero, Huitzilopochtli, and by extension the warriors,[1] is one of the most important Gods in the Central Mexico during the late post classic period. Xihuitl means "year" as well as "turquoise" and "fire". So Xiuhtecuhtli represents God of Fire and Time, the Turquoise Lord. If you were alive during the Aztec Period and were a warrior or a ruler, one of the gods you would have spent a lot of time praying to was the God of Fire.

This figure of a young man dressed with a loincloth and a pair of sandals with solar rays on heels. His right hand which appear to be in motion, was used to hold standards. His headdress decorated with a band of disk. His eyes has seashell and obsidian inlays. He carries his weapon on his back which is his characteristic emblem, the xiuhcóatl( spirit form, of the Aztec fire god Xiuhtecuhtli )or “snake of turquoises”. The tail of the snake formed by the combination of a trapezium and a ray that constitutes the glyph of the year. [2]

This large and imposing figure was donated in the 19th century by Josefa Atecechea to the Museo Nacional de Antropologia, INAH, in Mexico City.[3]

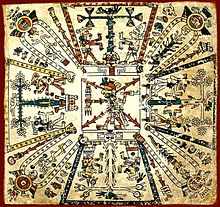

The pre-Hispanic manuscripts, Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, depicts specific aspects of the tonalpohualli, the sacred 260-day Mesoamerican augural cycle. The painted manuscript divides the world into five parts. The four directions are distributed around a sacred center, which would complete this horizontal vision of the universe as the fifth direction, is the domain of Xiuhtecuhtli. At the end of a 52-year cycle it was feared that the gods would discontinue their contract with mankind. To appease them, at the end of such a cycle feasts were held in their honor, where Xiuhtecuhtli as the god of fire united the other directions and brought the universe to a new cycle.[4]

Workshops

Aztec artisians worked in household craft workshops. In late 1980's, specialized workshops have been discovered at an archaeological project site near the town of Otumba, southeast of Teotihuacan. Those workshops manhufactured obsidian core-blade, mold-made ceramics, cotton and maguey-fiber textile. The excavations found that the whole neighborhoods specificalized in certain products because of the distribution pattern. The Otumba industries shows the Aztec artisans participated in network of raw matrial souces, manufactureing, and trade. The highest production period was between the mid-15th century and mid-16 century.[5]

Reference[edit]

- ^ Townsend, Richard (2009). The Aztec. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 187.

- ^ "Xiuhtecuhtli de Cozcatlan - unknown". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ "The Aztec Empire".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Codex Fejérváry-Mayer".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Townsend, Richard (2009). The Aztec. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 197.

| This is a user sandbox of Maggie5669. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |