User:Mr. Ibrahem/Major depressive disorder

| Major depressive disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Clinical depression, major depression, unipolar depression, unipolar disorder, recurrent depression |

| |

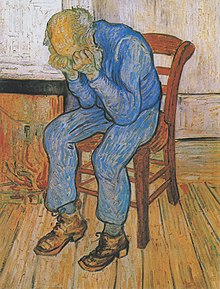

| Sorrowing Old Man ('At Eternity's Gate') by Vincent van Gogh (1890) | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Low mood, low self-esteem, loss of interest in normally enjoyable activities, low energy, pain without a clear cause[1] |

| Complications | Self-harm, suicide[2] |

| Usual onset | 20s–30s[3][4] |

| Duration | > 2 weeks[1] |

| Causes | Genetic, environmental, and psychological factors[1] |

| Risk factors | Family history, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, substance abuse[1][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Bipolar disorder, ADHD, sadness[3] |

| Treatment | Counseling, antidepressant medication, electroconvulsive therapy, exercise[5][1] |

| Frequency | 163 million (2017)[6] |

Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known simply as depression, is a mental disorder characterized by at least two weeks of low mood that is present across most situations.[1] It is often accompanied by low self-esteem, loss of interest in normally enjoyable activities, low energy, and pain without a clear cause.[1] Those affected may also occasionally have false beliefs or see or hear things that others cannot.[1] Some people have periods of depression separated by years in which they are normal, while others nearly always have symptoms present.[3] Major depressive disorder can negatively affect a person's personal life, work life, or education as well as sleeping, eating habits, and general health.[1][3] About 2–8% of adults with major depression die by suicide,[2][7] and about 50% of people who die by suicide had depression or another mood disorder.[8]

The cause is believed to be a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors.[1] Risk factors include a family history of the condition, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, and substance abuse.[1][3] About 40% of the risk appears to be related to genetics.[3] The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the person's reported experiences and a mental status examination.[9] There is no laboratory test for the disorder.[3] Testing, however, may be done to rule out physical conditions that can cause similar symptoms.[9] Major depression is more severe and lasts longer than sadness, which is a normal part of life.[3] Since 2016, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommended screening for depression among those over the age 12,[10][11] while a 2005 Cochrane review found that the routine use of screening questionnaires has little effect on detection or treatment.[12]

Those with major depressive disorder are typically treated with counseling and antidepressant medication.[1] Medication appears to be effective, but the effect may only be significant in the most severely depressed.[13][14] It is unclear whether medications affect the risk of suicide.[15] Types of counseling used include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy.[1][16] If other measures are not effective, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be considered.[1] Hospitalization may be necessary in cases with a risk of harm to self and may occasionally occur against a person's wishes.[17]

Major depressive disorder affected approximately 163 million people (2% of the world's population) in 2017.[6] The percentage of people who are affected at one point in their life varies from 7% in Japan to 21% in France.[4] Lifetime rates are higher in the developed world (15%) compared to the developing world (11%).[4] The disorder causes the second-most years lived with disability, after lower back pain.[18] The most common time of onset is in a person's 20s and 30s.[3][4] Females are affected about twice as often as males.[3][4] The American Psychiatric Association added "major depressive disorder" to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980.[19] It was a split of the previous depressive neurosis in the DSM-II, which also encompassed the conditions now known as dysthymia and adjustment disorder with depressed mood.[19] Those currently or previously affected may be stigmatized.[20]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Depression". NIMH. May 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ a b Richards, C. Steven; O'Hara, Michael W. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity. Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-979704-2. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k American Psychiatric Association (2013), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, pp. 160–68, ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8, retrieved 22 July 2016

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Kessler RC, Bromet EJ (2013). "The epidemiology of depression across cultures". Annual Review of Public Health. 34: 119–38. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. PMC 4100461. PMID 23514317.

- ^ Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE (September 2013). Mead GE (ed.). "Exercise for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD004366. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. PMID 24026850.

- ^ a b GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (November 10, 2018). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet. 392 (10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. PMC 6227754. PMID 30496104. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

{{cite journal}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Strakowski, Stephen; Nelson, Erik (2015). Major Depressive Disorder. Oxford University Press. p. PT27. ISBN 978-0-19-026432-1. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Bachmann, S (6 July 2018). "Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (7): 1425. doi:10.3390/ijerph15071425. PMC 6068947. PMID 29986446.

Half of all completed suicides are related to depressive and other mood disorders

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Patton, Lauren L. (2015). The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-118-92928-5. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Baumann LC, Davidson KW, Ebell M, García FA, Gillman M, Herzstein J, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Owens DK, Phillips WR, Phipps MG, Pignone MP (January 2016). "Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 315 (4): 380–87. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18392. PMID 26813211.

- ^ Siu AL (March 2016). "Screening for Depression in Children and Adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (5): 360–66. doi:10.7326/M15-2957. PMID 26858097.

- ^ Gilbody S, House AO, Sheldon TA (October 2005). "Screening and case finding instruments for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD002792. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002792.pub2. PMC 6769050. PMID 16235301.

- ^ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

- ^ Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLoS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Braun C, Bschor T, Franklin J, Baethge C (2016). "Suicides and Suicide Attempts during Long-Term Treatment with Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis of 29 Placebo-Controlled Studies Including 6,934 Patients with Major Depressive Disorder". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 85 (3): 171–79. doi:10.1159/000442293. PMID 27043848.

- ^ Driessen E, Hollon SD (September 2010). "Cognitive behavioral therapy for mood disorders: efficacy, moderators and mediators". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 33 (3): 537–55. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.005. PMC 2933381. PMID 20599132.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2006). American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 780. ISBN 978-0-89042-385-1. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hersen, Michel; Rosqvist, Johan (2008). Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment, Volume 1: Adults. John Wiley & Sons. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-470-17356-5. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Strakowski, Stephen M.; Nelson, Erik (2015). "Introduction". Major Depressive Disorder. Oxford University Press. p. Chapter 1. ISBN 978-0-19-020618-5. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.