User:Mykie0520/Cybersex trafficking

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft[edit]

Lead[edit]

Article body[edit]

Internet platforms[edit]

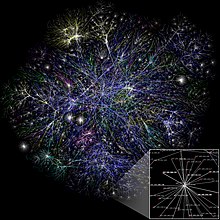

Cybersex trafficking is partly an internet-based crime.[1] Perpetrators use social media networks,[2] videoconferences, dating pages, online chat rooms, mobile apps,[3] dark web sites,[4][5] and other pages and domains.[6] They also use Telegram[7] and other cloud-based instant messaging[8] and voice over IP services, as well as peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms, virtual private networks (VPN),[9] and Tor protocols and software, among other applications, to carry out activities anonymously.

Consumers have made payments to traffickers, who are sometimes the victim's family members, using Western Union, PayPal, and other electronic payment systems.[10]

Dark web[edit]

Cybersex trafficking occurs commonly on some dark websites,[4] where users are provided sophisticated technical cover against identification.[5]

Social media[edit]

Perpetrators use Facebook[11][12][8] and other social media technologies.[5][2]

Videotelephony[edit]

Cybersex trafficking occurs on Skype[13][14][5] and other videoconferencing applications.[15][16] Pedophiles direct child sex abuse using its live streaming services.[13][5][11]

Service Platforms[edit]

Perpetrators use Craigslist and other service platforms to engage in cybersex trafficking.Sex crimes on Craigslist include the involvement of underage girls being sex trafficked through the service platform.[17]

Combating the crime[edit]

Authorities, skilled in online forensics, cryptography, and other areas,[18] use data analysis and information sharing to fight cybersex trafficking.[19] Deep learning, algorithms, and facial recognition are also hoped to combat the cybercrime.[20] Flagging or panic buttons on certain videoconferencing software enable users to report suspicious people or acts of live streaming sexual abuse.[21] Investigations are sometimes hindered by privacy laws that make it difficult to monitor and arrest perpetrators.[22] Conviction rates of perpetrators are low.[23]

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO-INTERPOL) collects evidence of live streaming sexual abuse and other sex crimes.[24] The Virtual Global Taskforce (VGT) comprises law enforcement agencies across the world who combat the cybercrime.[25] The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) funds training for police to identify and address the cybercrime.[23]

Multinational technology companies, such as Google, Microsoft, and Facebook, collaborate, develop digital tools, and assist law enforcement in combating it.[20]

On April 11, 2018, former president Donald Trump signed the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking of 2017(FOSTA).[26]The legislation was created with the intention for states and prosectors to more easily prosecute sex traffickers and clarifies that S230 immunity does not protect against those who uses their ICSs for participating in sex trafficking activities.[27]

Education[edit]

The Ministry of Education Malaysia introduced cybersex trafficking awareness in secondary school syllabuses.[28]

References

- ^ Smith, Nicola; Farmer, Ben (May 20, 2019). "Oppressed, enslaved and brutalised: The women trafficked from North Korea into China's sex trade". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Webcam slavery: tech turns Filipino families into cybersex child traffickers". Reuters. June 17, 2018.

- ^ "Children at risk of increased online sexual exploitation – Andrew Bevan". The Scotsman. May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b "Online child sex abuse rises with COVID-19 lockdowns: Europol". Reuters. May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Cheap tech and widespread internet access fuel rise in cybersex trafficking". NBC News. June 30, 2018.

- ^ "Senate to probe rise in child cybersex trafficking". The Philippine Star. November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Bithumb delists Monero amid Nth room sex scandal". Cryptopolitan. May 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "Five years in jail for "rape at a distance" for online abuser". The Brussels Times. September 26, 2018.

- ^ "No country is free from child sexual abuse, exploitation, UN's top rights forum hears". UN News. March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Federal Way man gets nearly 20 years in prison for directing child rape over Internet". Q13 Fox News. August 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "First paedophile in NSW charged with cybersex trafficking". the Daily Telegraph. March 27, 2017.

- ^ "Chasing Shadows: Can technology save the slaves it snared?". Thomson Reuters Foundation. June 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "Australian cyber sex trafficking 'most dark and evil crime we are seeing'". ABC News. September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Former UK army officer jailed for online child sex abuse". Reuters. May 22, 2019.

- ^ "PHILIPPINES Even 2-month-old babies can be cybersex victims – watchdog". Rappler. June 29, 2017.

- ^ "Global taskforce tackles cybersex child trafficking in the Philippines". Reuters. April 15, 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Chelsea (2020-07-14). ""Craigslist is Nothing More than an Internet Brothel": Sex Work and Sex Trafficking in U.S. Newspaper Coverage of Craigslist Sex Forums". The Journal of Sex Research. 58 (6): 681–693. doi:10.1080/00224499.2020.1786662. ISSN 0022-4499.

- ^ "Global taskforce tackles cybersex child trafficking in the Philippines". Reuters. April 15, 2019.

- ^ "Australian cyber sex trafficking 'most dark and evil crime we are seeing'". ABC News. September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "Chasing Shadows: Can technology save the slaves it snared?". Thomson Reuters Foundation. June 17, 2018.

- ^ "Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children" (PDF). UNODC. 2015.

- ^ "Cheap tech and widespread internet access fuel rise in cybersex trafficking". NBC News. June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Safe from harm: Tackling online child sexual abuse in the Philippines". UNICEF Blogs. June 7, 2016.

- ^ "No country is free from child sexual abuse, exploitation, UN's top rights forum hears". UN News. March 3, 2020.

- ^ "Child Sexual Exploitation". Europol. 2020.

- ^ Sanchez, Alexandra (April 1, 2020). ""Fosta: A Necessary Step in Advancement of the Women's Rights Movement."". Touro Law Review. 36: 637–62.

- ^ McKnelly, Megan (2019). "Untangling SESTA/FOSTA: How the Internet's "Knowledge" Threatens Anti-Sex Trafficking Law" (PDF). doi:10.15779/Z384J09X96.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Teo: Cybersex and human trafficking now part of school syllabus". The Star. October 2, 2019.