Virginia Hall

Virginia Hall | |

|---|---|

Virginia Hall receiving the Distinguished Service Cross in 1945 from OSS chief General Donovan | |

| Born | Virginia Hall April 6, 1906 Baltimore, Maryland |

| Died | July 8, 1982 (aged 76) Rockville, Maryland |

| Cause of death | natural |

| Burial place | Pikesville, Maryland |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater |

|

| Spouse | Paul Gaston Goillot |

| Parents |

|

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service branch | SOE (1940–44) OSS (1944–45) CIA (SAD) (1951–66) |

| Service years | 1940–1966 |

| Codename | Diane |

| Codename | Marie Monin |

| Codename | Germaine |

| Codename | Marie of Lyon |

| Codename | Camille |

| Operations | Operation Jedburgh |

| Other work | US Department of State (1931–39) |

Virginia Hall Goillot MBE (6 April 1906 – 8 July 1982[2]) was an American spy with the British Special Operations Executive during World War II and later with the American Office of Strategic Services and the Special Activities Division of the Central Intelligence Agency. She was known by many aliases, including "Marie Monin", "Germaine", "Diane", "Marie of Lyon", "Camille",[3][4] and "Nicolas".[1] The Germans gave her the nickname Artemis. The Gestapo reportedly considered her "the most dangerous of all Allied spies".[5]

Early life

Hall was born in Baltimore, Maryland and attended Roland Park Country School and then the prestigious Radcliffe College and Barnard College (Columbia University),[6] where she studied French, Italian and German. She wanted to finish her studies in Europe. With help from her parents, she travelled the Continent and studied in France, Germany, and Austria, finally landing an appointment as a Consular Service clerk at the American Embassy in Warsaw, Poland in 1931. Hall had hoped to join the Foreign Service, but suffered a setback around 1932 when she accidentally shot herself in the left leg while hunting in Turkey. The leg was later amputated from the knee down, and replaced with a wooden appendage which she named "Cuthbert". The injury foreclosed whatever chance she might have had for a diplomatic career, and she resigned from the Department of State in 1939. Thereafter she attended graduate school at American University in Washington, DC.[7]

World War II

The coming of war that year found Hall in Paris. She joined the Ambulance Service before the fall of France and ended up in Vichy-controlled territory when the fighting stopped in the summer of 1940.

Special Operations Executive

Hall made her way to London and volunteered for Britain's newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE), which sent her back to Vichy in August 1941. She spent the next 15 months there, helping to coordinate the activities of the French Underground in Vichy and the occupied zone of France. At the time she had the cover of a correspondent for the New York Post.[4]

When the Germans suddenly seized all of France in November 1942, Hall barely escaped to Spain. Rather whimsically, her artificial foot had its own codename ("Cuthbert"). According to Dr. Dennis Casey of the U.S. Air Force Intelligence Agency, the French nicknamed her "la dame qui boite" and the Germans put "the limping lady" on their most wanted list.[8] Before making her escape, she signalled to SOE that she hoped Cuthbert would not give trouble on the way. The SOE, not understanding the reference, replied, "If Cuthbert troublesome, eliminate him". Journeying back to London (after working for SOE for a time in Madrid), in July 1943 she was quietly made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[9]

Office of Strategic Services

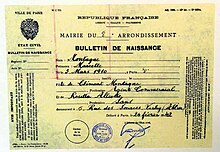

Virginia Hall joined the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Special Operations Branch in March 1944 and asked to return to occupied France. She hardly needed training in clandestine work behind enemy lines, and OSS promptly granted her request and landed her from a British MTB in Brittany (her artificial leg having kept her from parachuting in) with a forged French identification certificate for Marcelle Montagne. Codenamed "Diane", she eluded the Gestapo and contacted the French Resistance in central France. She mapped drop zones for supplies and commandos from England, found safe houses, and linked up with a Jedburgh team after the Allied Forces landed at Normandy. Hall helped train three battalions of Resistance forces to wage guerrilla warfare against the Germans and kept up a stream of valuable reporting until Allied troops overtook her small band in September. [citation needed]

Post war

In 1950, Hall married OSS agent Paul Goillot. In 1951, she joined the Central Intelligence Agency working as an intelligence analyst on French parliamentary affairs. She worked alongside her husband as part of the Special Activities Division.

Hall retired in 1966 to a farm in Barnesville, Maryland.

Death

Virginia Hall Goillot died at the Shady Grove Adventist Hospital in Rockville, Maryland on 8 July 1982, aged 76.[10] She is buried in the Druid Ridge Cemetery, Pikesville, Baltimore County, Maryland.[11]

Awards

For her efforts in France, General William Joseph Donovan in September 1945 personally awarded Hall a Distinguished Service Cross — the only one awarded to a civilian woman in World War II.[12][13] President Truman wanted a public award of the medal; however Hall demurred, stating she was "Still operational and most anxious to get busy." She was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

Legacy

Her story was told in The Wolves at the Door : The True Story of America's Greatest Female Spy by Judith L. Pearson (2005) The Lyons Press, ISBN 1-59228-762-X.

A biography exists in French: L'Espionne. Virginia Hall, une Américaine dans la guerre, by Vincent Nouzille (2007) Fayard (Paris), a book reviewed by British historian M.R.D. Foot in "Studies in Intelligence", Vol 53, N°1[2]. She was honoured again in 2006, at the French and British embassies for her courageous work.

Sources

- Marcus Binney, The Women Who Lived for Danger: The Women Agents of SOE in the Second World War, London, Hodder & Stoughton, 2002, ISBN 0-340-81840-9, pp. 111–38 ("Virginia Hall") and passim.

References

- ^ a b "The People of the CIA ... — Central Intelligence Agency". Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- ^ Benson, Kit and Morgan (May 21, 2006). "Virginia Hall". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- ^ "CIA Kids Page – History – Virginia Hall". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 2006-12-27.

- ^ a b "Obituary of Georges Bégué". Daily Telegraph. January 29, 1994. p. 15. Retrieved 2014-07-24. Georges Bégué

- ^ Meyer,Roger (October 2008). "World War II's Most Dangerous Spy" The American Legion Magazine p. 54

- ^ Curriculum

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.usnews.com/usnews/culture/articles/030127/27heyday.hall.htm

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/books-and-monographs/oss/art05.htm

- ^ http://www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/virginia-hall/

- ^ Virginia Hall Goillot at Find a Grave

- ^ http://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/index.html?dod-date=512

- ^ http://blogs.archives.gov/todaysdocument/2011/05/12/may-12-virginia-hall-of-the-oss/

External links

- "Ambassadors to honor female ww1 spy" by Ben Nuckols, Associated Press, 10 December 2006.

- Special Operations article and Featured story about Virginia Hall on the CIA web site

- Times Online Article

- Article by MRD Foot in Studies in Intelligence vol 53 N°1 [3]

- Virginia Hall at Find a Grave

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: https://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/oss/art05.htm The People of the CIA ...Making an Impact: Virginia Hall

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: https://www.odci.gov/cia/publications/oss/art05.htm The People of the CIA ...Making an Impact: Virginia Hall

- 1906 births

- 1982 deaths

- American spies

- Female wartime spies

- New York Post people

- Special Operations Executive personnel

- French Resistance members

- World War II spies

- Female resistance members of World War II

- Members of the Order of the British Empire

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United States)

- American women in World War II

- People from Baltimore

- Barnard College alumni

- Radcliffe College alumni

- American University alumni

- People of the Office of Strategic Services

- People of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Analysts of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Death in Maryland

- Burials at Druid Ridge Cemetery

- 20th-century American writers

- American amputees

- Honorary Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire