Walt McDougall

| Walt McDougall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 10, 1858 Newark, New Jersey |

| Died | March 6, 1938 (aged 80) Waterford, Connecticut |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

Notable works | Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz |

| Signature | |

Walter Hugh McDougall (February 10, 1858 – March 6, 1938) was an American cartoonist. He produced some of the earliest full color newspaper comic strips, and was one of the first producers of regular political cartoons in American daily papers.[1][2] His satirical cartoons, published in outlets such as the New York World and The North American, were influential in the 1884 U.S. presidential election, and soon after political cartoons became a fixture in American papers. He also drew children's comic strips, including Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz written by L. Frank Baum, and has been called the first syndicated cartoonist for his contributions to the weekly columns of humorist Bill Nye. His books include The Hidden City (1891) and The Rambillicus Book (1903).

Biography

Walter Hugh McDougall was born in Newark, New Jersey, the son of John Alexander McDougall (1810–1894),[3] a painter and close associate of writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Washington Irving.[4] Walt attended a military academy, and from the age of 16 was self-educated. He began his professional work in 1876 with the New York Daily Graphic, which three years earlier had become the nation's first illustrated daily newspaper. He also sold early works to Harper's Weekly and Puck.[5][6] For a time he was part owner of the Newark newspaper The Suburban.[7] He married F. M. Burns in 1878.[6]

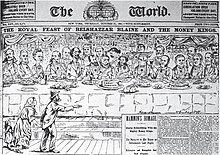

He began working for the New York World in 1884, and a cartoon printed on August 10 of that year became the World's first political cartoon.[8] Several of his cartoons were influential in the 1884 presidential election. One, likening nominee James G. Blaine's dinner with millionaires and plutocrats shortly before the election to Belshazzar's feast of the Bible, is credited with contributing to Blaine's narrow loss to Grover Cleveland. The cartoon, entitled "The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings" and co-drawn by Valerian Gribayedoff, was reprinted on billboards across New York and Blaine lost the state, and thus the election, by little over 1,000 votes.[9] Author Michael R. Smith writes McDougall and Gribayedoff "may have created the most influential political cartoon in United States history."[10] "Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings" elevated the prominence of political cartoons, which soon after became a regular feature in daily newspapers nationwide.[11][12][13]

McDougall is sometimes credited with the first color cartoon in an American newspaper: a May 21, 1893, cartoon on the cover to the World's first color Sunday comic supplement.[5][14][15] However, the first color cartoon has also been attributed to an April 2, 1893, George Turner cartoon in the New York Recorder.[16] McDougall, in collaboration with Mark Fenderson, is also credited with the first American color comic strip: "The Unfortunate Fate of a Well-Intentioned Dog", which first appeared in the World on February 4, 1894.[5][a] He illustrated the popular newspaper column of humorist Bill Nye for many years, and has thus been called the first syndicated cartoonist.[5] While his caricature of Nye was widely recognized, it was reportedly disliked by Nye himself.[18]

He illustrated the comic strip Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz (1904–1905), written by L. Frank Baum, as well as his own novel The Hidden City (1891) and story books such as Comic Animals (1890) and The Rambillicus Book (1903). His comic strips included Fatty Felix, Hank the Hermit, Absent-Mined Abner, and Peck's Bad Boy.[5] Another noted political cartoon appeared in Philadelphia's The North American in 1903: when Pennsylvania Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker—long mocked by cartoonists as a parrot—championed a libel bill banning the portrayal of politicians as animals, McDougall caricatured Pennypacker and his supporters as a tree, beer stein, potato, turnip, squash, and chestnut burr.[19][20]

McDougall released an autobiography, This is the Life!, in 1926, and died from a self-inflicted gunshot at his home in Waterford, Connecticut, on March 6, 1938, at the age of 80.[5][21][22]

Works

-

"The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings" (1884) likens James G. Blaine to the biblical Belshazzar.

-

"The Possibilities of the Broadway Cable Car" (1893), one of the first color cartoons in American newspapers

-

Supporters of the "Pennsylvania anti-cartoon bill" portrayed in compliance with restrictions on animal caricatures (1903)

As author

- Fun and Fancy - Wonder Tales for the Children from 7 to 70. Newark, NJ: Charles E. Graham & Co. 1885.

- Comic Animals. New York: Charles E. Graham & Co. 1890.

- The Hidden City. New York: Cassell. 1891.

- The Un-Authorized History of Columbus. Newark, NJ: McDougall Publishing Co. 1892.

- The Rambillicus Book. Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co. 1903.

- Peck's Bad Boy and his Country Cousin Cynthia. Chicago: Thompson & Thomas. 1907.

- Peck's Bad Boy and his Chums. Chicago: Stanton & Van Vliet Co. 1908.

- This is the Life!. New York: A.A. Knopf. 1926.

As illustrator

- Nye, Edgar W., and James Whitcomb Riley. Nye and Riley's Railway Guide. Chicago: Dearborn. 1888.[b]

- Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz. Syndicated. 1904–05. Reprinted by Sunday Press, Palo Alto, 2009.

See also

Notes

- ^ Roy L. McCardell, in discussing the origin of the Sunday color comics supplement, credits the "first real appearance" of the color supplement to the New York World on November 18, 1894: "There had been attempts at colored supplements before that date; but they had all failed. The Recorder, then a daily newspaper in New York City, tried to print one; but the result was too horrible—the different colored inks would not stay in their right places, and the supplement was a splotch of discolor. In Chicago, during the World's Fair, two papers tried to print colored supplements; but the result was even worse than that of the Recorder's attempt."[17]: 763

- ^ Re-titled and republished as Nye and Riley's Wit and Humor (1896) and On the "Shoestring Limited" (1905)[23]

References

- ^ Douglas, George H. (1999). The Golden Age of the Newspaper. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-313-31077-5.

- ^ Sterling, Guy G. (2014). The Famous, the Familiar and the Forgotten. Xlibris Corporation. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4990-7990-6.

- ^ Johnson, Dale T. (1990). American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-0-87099-597-2.

- ^ "John A. M'Dougall Dead". The Evening World. July 30, 1894. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Marschall 1976, p. 469.

- ^ a b Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson (1908). Who's Who in America. Marquis Who's Who. p. 1203.

- ^ Speed, John Gilmer (December 29, 1891). "M'Dougall, the Caricaturist". The Wichita Daily Eagle. p. 2. Syndicated article reprinted here by Allan Holtz.

- ^ Harvey 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Hess & Northrop 2011, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Smith, Michael R. (2002). "Cartoons, Comics, and Caricature". In Sloan, W. David; Parcell, Lisa Mullikin (eds.). American Journalism: History, Principles, Practices. McFarland. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-0-7864-1371-3.

- ^ Lordan 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Kazin, Michael; Edwards, Rebecca; Rothman, Adam (2009). The Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton University Press. p. 116. ISBN 1-4008-3356-6.

- ^ Dewey, Donald (2008). The Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons. NYU Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8147-2015-8.

- ^ Harvey 2014, p. 20.

- ^ White, David Manning; Abel, Robert H., eds. (1963). The Funnies: An American Idiom. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe. p. 91.

- ^ Lee, Judith Yaross (2000). Defining New Yorker Humor. University Press of Mississippi. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-57806-198-3.

- ^ McCardell, Roy L. (1905). "Opper, Outcault and Company: The Comic Supplement and the Men who Make It". Everybody's Magazine: 763–772.

- ^ "Bill Nye". Book of the Royal Blue. 10 (11): 9–12. August 1907.

- ^ Hess & Northrop 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Lordan 2006, pp. 58–60.

- ^ "Walt M'Dougall Killed by Bullet". The New York Times. March 7, 1938. p. 10.

- ^ Greer, Louise (March 10, 1938). "Victoria Writer Pays Tribute to Late Cartoonist". The Victoria Advocate. p. 5.

- ^ Wade, Clyde G. (2016). "Bill Nye". In Gale, Steven H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of American Humorists. Routledge. pp. 340–344. ISBN 978-1-317-36227-2.

- Harvey, Robert C. (2014). Insider Histories of Cartooning: Rediscovering Forgotten Famous Comics and Their Creators. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62674-354-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hess, Stephen; Northrop, Sandy (2011). American Political Cartoons: The Evolution of a National Identity, 1754–2010. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-1119-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lordan, Edward J. (2006). Politics, Ink: How America's Cartoonists Skewer Politicians, from King George III to George Dubya. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-3638-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marschall, Richard (1976). "McDougall, Walter Hugh (1858–1938)". In Horn, Maurice (ed.). The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Vol. 2. New York: Chelsea House. p. 469.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Walt McDougall at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Walt McDougall at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Guide to the Bill Loughman Collection of Walt McDougall and Valerian Gribayedoff Cartoon Tearsheets at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

- Walt McDougall photograph, 1927 at Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- 1858 births

- 1938 deaths

- 19th-century American artists

- 20th-century American artists

- American cartoonists

- American editorial cartoonists

- American caricaturists

- American children's book illustrators

- American comic strip cartoonists

- Artists who committed suicide

- Artists from Newark, New Jersey

- American children's writers