Woodhenge

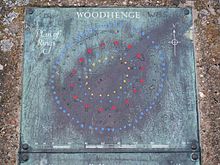

Concrete pillars marking Woodhenge's postholes | |

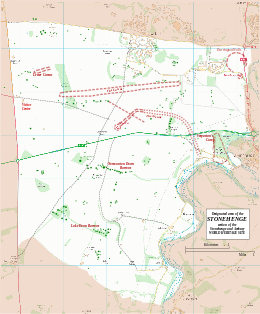

Map showing Woodhenge and Durrington Walls within the Stonehenge section of the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site | |

| Location | OS SU150434 |

|---|---|

| Region | Wiltshire |

| Coordinates | 51°11′22″N 1°47′09″W / 51.1894°N 1.78576°W |

| Type | henge |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1926–8 |

| Archaeologists | Ben and Maud Cunnington |

| Condition | feint earthworks, concrete posts |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | English Heritage |

| Designated | 1986[1] |

| Reference no. | 373 |

| Designated | 1929 |

| Reference no. | 1009133[2] |

Woodhenge is a Neolithic Class II henge and timber circle monument within the Stonehenge World Heritage Site in Wiltshire, England. It is 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of Stonehenge, in Durrington parish, just north of the town of Amesbury.

Discovery

[edit]Woodhenge was believed to be identified from an aerial photograph taken by pilot and World War I veteran Gilbert Insall, VC, in 1926,[3] during the same period that an aerial archaeology survey of Wessex[4] by Alexander Keiller and O. G. S. Crawford (Archaeology Officer for the Ordnance Survey) was being undertaken. Although some sources attribute the identification of the henge to Crawford, he credits the discovery[3] to Insall.

In fact, the site had been found in the early 19th century, when it was described as an earthwork and thought to be a disc barrow. It was originally called "Dough Cover." A professional excavation of the site was undertaken between 1926 and 1929 by Maud Cunnington and Ben Cunnington.[5] They confirmed that it was a henge.[5]

Date

[edit]Pottery from the excavation was identified as being consistent with the grooved ware style of the middle Neolithic, although later beaker sherds were also found. Thus, the structure was probably built during the period of cultural similarities commonly known as the Beaker. The Bell Beaker culture spans both the Late Neolithic and Britain's early Bronze Age and includes both the distinctive "bell beaker" type ceramic vessels for which the cultural grouping is known, and other local styles of pottery from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.

While construction of the timber monument was probably earlier, the ditch has been dated to between 2470 and 2000 BCE, which would be about the same time as, or slightly later than, construction of the stone circle at Stonehenge.[6] Radiocarbon dating of artefacts shows that the site was still in use around 1800 BC.[7]

Structure

[edit]

The site consists of six concentric oval rings of postholes, the outermost being about 43 by 40 metres (141 by 131 ft) wide. They are surrounded first by a single flat-bottomed ditch, 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) deep and up to 12 metres (39 ft) wide, and finally by an outer bank, about 10 metres (33 ft) wide and 1 metre (3.3 ft) high.[5] With an overall diameter measuring 110 metres (360 ft) (including bank and ditch), the site had a single entrance to the north-east.[7]

At the centre of the rings was a crouched inhumation of a child which Cunnington interpreted as a dedicatory sacrifice, its skull having been split.[8] Subsequent theories have indicated that the weight and pressure of the soil over the years could have caused the skull to fragment.[9] After excavation, the remains were taken to London, where they were destroyed during The Blitz, making further examination impossible. Cunnington also found a crouched inhumation of a teenager within a grave dug in the eastern section of the ditch, opposite the entrance.[5]

Most of the 168 post holes held wooden posts, although Cunnington found evidence that a pair of standing stones may have been placed between the second and third post hole rings. Excavations in 2006 indicated that there were at least five standing stones on the site,[6] arranged in a "cove". The deepest post holes measured up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) and are believed to have held posts which reached as high as 7.5 metres (25 ft) above ground. Those posts would have weighed up to 5 tons, and their arrangement was similar to that of the bluestones at Stonehenge. The positions of the postholes are currently marked with modern concrete posts – a simple and informative method of displaying the site.

Further comparisons with Stonehenge were quickly noticed by Cunnington: both have entrances oriented approximately to the midsummer sunrise, and the diameters of the timber circles at Woodhenge and the stone circles at Stonehenge are similar.

Relationship with other monuments

[edit]Over 40 years after the discovery of Woodhenge, another timber circle of comparable size was discovered in 1966, 70 metres (230 ft) to the north. Known as the Southern Circle, it lies inside what came to be known as the Durrington Walls henge enclosure.

There are various theories about possible timber structures that might have stood on and about the site, and their purpose, but it is likely that the timbers were free-standing, rather than part of a roofed structure.[6] For many years, the study of Stonehenge had overshadowed work on the understanding of Woodhenge. Recent ongoing investigations as part of the Stonehenge Riverside Project are now starting to cast new light on the site and on its relationship with neighbouring sites and Stonehenge.

Theories have emerged in which the sites may all be part of a layout in which the structures were linked by roads, and which incorporated the natural features of the River Avon. One of these paths, consisting of a series of wide parallel banks and ditches referred to as Stonehenge Avenue, crosses the ridge between the two sites that would otherwise make them both visible from one another,[10] possibly connecting them physically as well as spiritually.

One suggestion is that the use of wood rather than stone may have held a special significance in the beliefs and practices involving the transformation between life and death,[5] possibly separating the two sites into separate "domains".[10] These theories have been supported by findings of bones of butchered pigs exclusively at Woodhenge, showing evidence of feasting, leaving Stonehenge as a site only inhabited by ancestral spirits, not living people.[10] These same possible representations (wood vs. stone) have also been seen in ritualistic megalithic sites on the island of Madagascar, at least 4,000 years after the erection of Woodhenge.[10]

See also

[edit]- List of archaeoastronomical sites by country

- Cuckoo Stone, a standing stone 500 metres to the west

- Avebury Henge

- Bluestonehenge

- Stonehenge

References

[edit]- ^ UNESCO World Heritage site No 373

- ^ Historic England. "Henge monuments at Durrington Walls and Woodhenge, a round barrow cemetery, two additional round barrows and four settlements (1009133)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ a b Crawford, Archaeology in the Field, 1953; page 49

- ^ Crawford/Keiller, Wessex from the Air, 1928

- ^ a b c d e Historic England. "Woodhenge (219050)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "Woodhenge". World Heritage Site. English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ a b "History and Research: Woodhenge". english-heritage.org.uk. English Heritage. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "Stonehenge. Woodhenge, the origins". stonehenge-stone-circle.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "Woodhenge is just as fascinating and mysterious as its famous neighbor, Stonehenge". The Vintage News. 2 May 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d Pitts, Mike (2008). "The Henge Builders". Archaeology. 61 (1). Retrieved 2 December 2015.