Wu experiment

The Wu experiment was a nuclear physics experiment conducted in 1956 by the Chinese American physicist Chien-Shiung Wu in collaboration with the Low Temperature Group of the US National Bureau of Standards.[1] The experiment's purpose was to establish whether or not conservation of parity (P-conservation), which was previously established in the electromagnetic and strong interactions, also applied to weak interactions. If P-conservation were true, a mirrored version of the world (where left is right and right is left) would behave as the mirror image of the current world. If P-conservation were violated, then it would be possible to distinguish between a mirrored version of the world and the mirror image of the current world.

The experiment established that conservation of parity was violated (P-violation) by the weak interaction. This result was not expected by the physics community, which had previously regarded parity as a conserved quantity. Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang, the theoretical physicists who originated the idea of parity nonconservation and proposed the experiment, received the 1957 Nobel Prize in physics for this result. Chien-Shiung Wu’s role in the discovery was mentioned in the Nobel prize acceptance speech[2], but was not honored until 1978, when she was awarded the first Wolf Prize.

History

In 1927, Eugene Wigner formalized the principle of the conservation of parity (P-conservation),[3] the idea that the current world and one built like its mirror image would behave in the same way, with the only difference that left and right would be reversed (for example, a clock which spins clockwise would spin counterclockwise if you built a mirrored version of it).

This principle was widely accepted by physicists, and P-conservation was experimentally verified in the electromagnetic and strong interactions. However, during the mid-1950s, certain decays involving kaons could not be explained by existing theories in which P-conservation was assumed to be true. There seemed to be two types of kaons, one which decayed into two pions, and the other which decayed into three pions. This was known as the τ–θ puzzle.[4]

Theoretical physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang did a literature review on the question of parity conservation in all fundamental interactions. They concluded that in the case of the weak interaction, experimental data neither confirmed nor refuted P-conservation.[5] Shortly after, they approached Chien-Shiung Wu, who was an expert on beta decay spectroscopy, with various ideas for experiments. They settled on the idea of testing the directional properties of beta decay in cobalt-60. Wu thereafter contacted Henry Boorse and Mark W. Zemansky, who had extensive experience in low-temperature physics. At the behest of Boorse and Zemansky, Wu contacted Ernest Ambler, of the National Bureau of Standards, who arranged for the experiment to be carried out in December 1956 in the NBS' low-temperature laboratories.[4]

Lee and Yang, who prompted the Wu experiment, were awarded the Nobel prize in physics in 1957, shortly after the experiment was performed. Wu’s role in the discovery was mentioned in the prize acceptance speech[2],but was not honored until 1978, when she was awarded the inaugural Wolf Prize.

The experiment

The experiment itself monitored the decay of cobalt-60 atoms, cooled to near absolute zero and aligned in a uniform magnetic field.[4] Cobalt-60 (60Co) is an unstable isotope of cobalt that decays by beta decay to the stable isotope nickel-60 (60Ni). During this decay, one of the neutrons in the cobalt-60 nucleus decays to a proton by emitting an electron (e−) and an electron antineutrino (νe). This changes the cobalt-60 nucleus into a nickel-60 nucleus. The resulting nickel nucleus, however, is in an excited state and promptly decays to its ground state by emitting two gamma rays (γ). Hence the overall nuclear equation of the reaction is:

Gamma rays are photons, and their release from the nickel-60 nuclei is an electromagnetic (EM) process. This is important because EM was known to respect P-conservation. Hence, the distribution of the emitted gamma rays acted as a control for the polarization of the emitted electrons via the weak interaction, as well as an indicator of the uniformity of the cobalt-60 atoms. Wu's experiment compared the distribution of gamma and electron emissions with the nuclear spins in opposite orientations. If the electrons were always found to be emitted in the same direction and in the same proportion as the gamma rays, P-conservation would be true. If there were a bias in the direction of decays, that is, if the distribution of electrons did not follow the distribution of the gamma rays, then P-violation would be established.

Materials and methods

The experimental challenge in this experiment was to obtain the highest possible polarization of the 60Co nuclei. Due to the very small magnetic moments of the nuclei as compared to electrons, high magnetic fields were required at extremely low temperatures, far lower than could be achieved by liquid helium cooling alone. The low temperatures were achieved using the method of adiabatic demagnetization. Radioactive cobalt was deposited as a thin surface layer on a crystal of cerium-magnesium nitrate, a paramagnetic salt with a highly anisotropic Landé g-factor.

The salt was magnetized along the axis of high g-factor, and the temperature was lowered to 1.2 K by pumping the helium to low pressure. Shutting off the horizontal magnetic field resulted in the temperature decreasing to about 0.003 K. The horizontal magnet was opened up, allowing room for a vertical solenoid to be introduced and switched on to align the cobalt nuclei either upwards or downwards. Only a negligible increase in temperature was caused by the solenoid magnetic field, since the magnetic field orientation of the solenoid was in the direction of low g-factor. This method of achieving high polarization of 60Co nuclei had been originated by Gorter[6] and Rose.[7]

The production of gamma rays was monitored using equatorial and polar counters as a measure of the polarization. Gamma ray polarization was continuously monitored over the next quarter-hour as the crystal warmed up and anisotropy was lost. Likewise, beta-ray emissions were continuously monitored during this warming period.[1]

Results

In the experiment carried out by Wu, the gamma ray polarization was approximately 60%.[1] That is, approximately 60% of the gamma rays were emitted in one direction, whereas 40% were emitted in the other. If P-conservation were true in beta decay, electrons would have no preferred direction of decay relative to the nuclear spin. However, Wu observed that the electrons were emitted in a direction preferentially opposite to that of the gamma rays. That is, most of the electrons favored a very specific direction of decay, opposite to that of the nuclear spin.[1] It was later established that P-violation was in fact maximal.[4][8]

The results greatly surprised the physics community.[4] Several researchers then scrambled to reproduce the results of Wu's group,[9][10] while others reacted with disbelief at the results. Wolfgang Pauli upon being informed by Georges M. Temmer, who also worked at the NBS, that P-conservation could no longer be assumed to be true in all cases, exclaimed "That's total nonsense!" Temmer assured him that the experiment's result confirmed this was the case, to which Pauli curtly replied "Then it must be repeated!"[4] By the end of 1957, further research confirmed the original results of Wu's group, and P-violation was firmly established.[4]

Mechanism and consequences

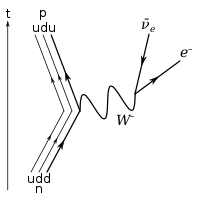

β−

decay of a neutron into a proton, electron, and electron antineutrino via an intermediate

W−

boson.

The results of the Wu experiment provide a way to operationally define the notion of left and right. This is inherent in the nature of the weak interaction. Previously, if the scientists on Earth were to communicate with a newly discovered planet’s scientist, and they had never met in person, it would not have been possible for each group to determine unambiguously the other group’s left and right. With the Wu experiment, it is possible to communicate to the other group what the words left and right mean exactly and unambiguously. The Wu experiment has finally solved the Ozma problem which is to give an unambiguous definition of left and right scientifically.[11]

At the fundamental level (as depicted in the Feynman diagram on the right), Beta decay is caused by the conversion of the negatively charged (−1/3 e) down quark to the positively charged (+2/3 e) up quark by emission of a

W−

boson; the

W−

boson subsequently decays into an electron and an electron antineutrino:

d

→

u

+

e−

+

ν

e.

The quark has a left part and a right part. As it walks across the spacetime, it oscillates back and forth from right part to left part and from left part to right part. From analyzing the Wu experiment’s demonstration of parity violation, it can be deduced that only the left part of down quarks decay and the weak interaction involves only the left part of quarks and leptons (or the right part of antiquarks and antileptons). The right part of the particle simply does not feel the weak interaction. If the down quark did not have mass it would not oscillate, and its right part would be quite stable by itself. Yet, because the down quark is massive, it oscillates and decays.[12]

From experiments such as the Wu experiment and the Goldhaber experiment, it was determined that massless neutrinos must be left-handed, while massless antineutrinos must be right-handed. Since it is currently known that neutrinos have a small mass, it has been proposed that right-handed neutrinos and left-handed antineutrinos could exist. These neutrinos would not couple with the weak Lagrangian and would interact only gravitationally, possibly forming a portion of the dark matter in the universe.[13]

See also

- Beta decay

- Neutrino

- Fermi's interaction

- Weak interaction

- Electroweak interaction

- The Ambidextrous Universe by Martin Gardner; book containing a lengthy popular discussion of parity and the Wu experiment

References

- ^ a b c d Wu, C. S.; Ambler, E.; Hayward, R. W.; Hoppes, D. D.; Hudson, R. P. (1957). "Experimental Test of Parity Conservation in Beta Decay" (PDF). Physical Review. 105 (4): 1413–1415. Bibcode:1957PhRv..105.1413W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1413.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in physics in 1957". The Nobel Prize. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^

Wigner, E. P. (1927). "Über die Erhaltungssätze in der Quantenmechanik". Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch Physikalische Klasse: 375–381.

- Reproduced in Wightman, A. S., ed. (1993). The Collected Works of Eugene Paul Wigner. Vol. Vol. A. Springer. p. 84. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-02781-3_7. ISBN 978-3-642-08154-5.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

- Reproduced in Wightman, A. S., ed. (1993). The Collected Works of Eugene Paul Wigner. Vol. Vol. A. Springer. p. 84. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-02781-3_7. ISBN 978-3-642-08154-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hudson, R. P. (2001). "Reversal of the Parity Conservation Law in Nuclear Physics". In Lide, D. R. (ed.). A Century of Excellence in Measurements, Standards, and Technology (PDF). NIST Special Publication 958. National Institute of Standards and Technology. ISBN 978-0849312472.

- ^ Lee, T. D.; Yang, C. N. (1956). "Question of Parity Conservation in Weak Interactions" (PDF). Physical Review. 104 (1): 254–258. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104..254L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.254.

- ^ Gorter, C. J. (1948). "A New Suggestion for Aligning Certain Atomic Nuclei". Physica. 14 (8): 504. Bibcode:1948Phy....14..504G. doi:10.1016/0031-8914(48)90004-4.

- ^ Rose, M. E. (1949). "On the Production of Nuclear Polarization". Physical Review. 75 (1): 213. Bibcode:1949PhRv...75Q.213R. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.75.213.

- ^ Ziino, G. (2006). "New Electroweak Formulation Fundamentally Accounting for the Effect Known as "Maximal Parity-Violation"" (PDF). International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 45 (11): 1993–2050. Bibcode:2006IJTP...45.1993Z. doi:10.1007/s10773-006-9168-2.

- ^ Garwin, R. L.; Lederman, L. M.; Weinrich, M. (1957). "Observations of the failure of conservation of parity and charge conjugation in meson decays: the magnetic moment of the free muon" (PDF). Physical Review. 105 (4): 1415–1417. Bibcode:1957PhRv..105.1415G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1415.

- ^ Ambler, E.; Hayward, R. W.; Hoppes, D. D.; Hudson, R. P.; Wu, C. S. (1957). "Further Experiments on Decay of Polarized Nuclei" (PDF). Physical Review. 106 (6): 1361–1363. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106.1361A. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.106.1361.

- ^ Gardner, M. (2005). The New Ambidextrous Universe: Symmetry and Asymmetry from Mirror Reflections to Superstrings (3rd Revised ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 215-218. ISBN 978-0-486-44244-0.

- ^ Lederman, L. M.; Hill, C. T. (2013). Beyond the God Particle. Prometheus Books. p. 125-126. ISBN 978-1-61614-802-7.

- ^ Drewes, M. (2013). "The Phenomenology of Right Handed Neutrinos". International Journal of Modern Physics E. 22 (8): 1330019. arXiv:1303.6912. Bibcode:2013IJMPE..2230019D. doi:10.1142/S0218301313300191.

Further reading

- Martin, W. C.; Coursey, J.; Dragoset, R. A. (July 1997). "The Fall of Parity". NIST Physical Measurement Laboratory.