Julius Martov

Julius Martov | |

|---|---|

| Юлий Мартов | |

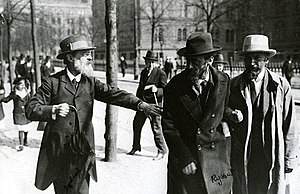

Martov in 1917 | |

| Born | Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum 24 November 1873 |

| Died | 4 April 1923 (aged 49) |

| Political party | Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, Mensheviks |

| Movement | Socialism, Marxism |

Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum[a] (24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923), better known as Julius Martov,[b] was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and the leader of the Mensheviks, a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). A close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to 1903, Martov broke with him following the RSDLP's ideological schism, after which Lenin led the opposing faction, the Bolsheviks.

Martov was born to a middle-class and politically active Jewish family in Constantinople. He was raised in Odessa and embraced Marxism after the Russian famine of 1891–1892. Martov briefly enrolled at Saint Petersburg Imperial University, but was later expelled and exiled to Vilna, where he developed influential ideas on worker agitation. Returning to Saint Petersburg in 1895, Martov collaborated with Vladimir Lenin to co-found the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, and after three years of Siberian exile moved to Western Europe with Lenin, where they became active members of the RSDLP and co-founded the party newspaper Iskra. At the second RSDLP Congress in 1903, a schism developed between their supporters; Martov became the leader of the Menshevik faction against Lenin's Bolsheviks.

After the February Revolution of 1917, Martov returned to Russia and led the faction of Mensheviks who opposed the Provisional Government. Following the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks came to power, Martov advocated an "all-socialist" coalition government, but found himself politically marginalised. He continued to lead the Mensheviks and denounced the Soviet government's repressive measures during the civil war, such as the Red Terror, while supporting the struggle against the Whites. In 1920, Martov left Russia for Germany, and the Mensheviks were outlawed a year later. He died from tuberculosis in 1923.

Early life

[edit]Martov was born to an educated and politically active Jewish family in Constantinople, Ottoman Empire.[1] Martov's grandfather, Alexander Osipovich Tsederbaum, was a prominent social activist. In the 1870s, his grandfather founded the first newspapers in Russia published in Hebrew and Yiddish. His father Joseph Alexandrovich worked for the Russian Association for Shipping and Trade. His sister was the fellow Menshevik leader Lydia Dan. Two of his three brothers, Sergei and Vladimir were also distinguished Mensheviks.[1]

In his early childhood he was dropped by his governess and broke his leg. The governess did not tell anyone about the incident and it was only noticed by his family after he started walking. His leg never healed properly and he suffered from a permanent limp.[2] This disability played a significant role in his life and how others perceived him. He suffered constant taunting throughout his childhood for his inability to keep up with other kids his age.[1]

Martov was raised in Odessa, but the pogrom against Odessa Jews in 1881 forced the family to move to St. Petersburg. The Tsederbaum family, like many others at the time, held the government responsible for the pogroms.

The Tsederbaum family was Jewish, but the children were given a secular education. Raised in a materialist environment, Martov later credited his upbringing for his adherence to socialism.[1] In his teens, he admired the Narodniks, but the famine crisis made him a Marxist: "It suddenly became clear to me how superficial and groundless the whole of my revolutionism had been until then, and how my subjective political romanticism was dwarfed before the philosophical and sociological heights of Marxism".[3]

Early political activities and exile

[edit]In 1891, Martov attended demonstrations at the funeral of Nikolai Shelgunov. Arrested in February 1892 for anti-tsarist activities, he was held in prison until May, when his grandfather paid bail of 300 rubles. That Autumn he enrolled at St Petersburg University, joined a Marxist group organized by Alexander Potresov, and was expelled, rearrested [Dec.], and held until May 1893. In this brief spell of liberty, he had tried to organize a Petersburg branch of the Emancipation of Labour group. Instead of accepting his grandfather's suggestion of emigrating to the United States of America, he chose to be exiled for two years in Vilna (now Vilnius).[4]

While living in exile in Vilna, Martov and others decided to shift from a strictly educational approach to a focus on agitation. The mass of Jewish workers in Vilna led them to decide to carry out their efforts in Yiddish.[5] Together with fellow Vilno Social Democrat, Arkady Kremer, Martov explained the strategy involving mass agitation and participating in Jewish strikes in the work On Agitation (1895). The plan detailed that workers were to see a need for broader political campaigning through participating in strikes, led by the Social Democrats as trade unions were banned under the Tsarist regime.[6] This led to the formulation of the ideology that led to the formation of the General Jewish Labour Bund in 1897 in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia.[5] However, Martov would eventually have a critical parallel role with Lenin in the opposition to the Bund as they would not recognize them as an autonomous section within the RSDLP.[7][5]

Martov returned to St Petersburg in October 1895, and helped to form the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, in which Lenin was a dominant figure. At this stage, "their friendship was so close that they agreed on the foundations of their world view",[8] despite or because of the contrasts in their personalities. Lenin was neat and restrained; Martov lively and chaotic. Martov took on the task of contacting workers at the Putilov factory, until his arrest in January 1896.

Martov was deported for three years to the village of Turukhansk in the Arctic, while Lenin was sent to Shushenskoye in the comparatively warm "Siberian Italy".[9] When his term of exile ended, he joined Lenin in Pskov, where together they planned to go abroad and launch a newspaper as a way of organising the scattered Marxist movement into a centrally run political party. In June 1900, before they left Russia, they returned together to St Petersburg, where they were followed and arrested but released after a few days.[10]

Forced to leave Russia and with other radical political figures living in exile, Martov settled in Munich, joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) and was one of the founders of the party journal Iskra.[11][12] Initially, Lenin and Martov were allies in disputes within the six member editorial board, on which Georgi Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism, had the casting vote. When the Iskra operation was transferred to London, in April 1902, Martov shared lodgings in Sidmouth Street[13] with the veteran Marxist, Vera Zasulich, close to where Lenin and his wife, Krupskaya had lodgings. While Lenin was working in the British Museum, Martov and Krupskaya together handled "a large proportion of routine wearying work", such as dealing with mail from Iskra supporters.[14] Trotsky believed that the rift between Martov and Lenin began in London, where Martov came under the influence of Zasulich "who was drawing him away from Lenin." He also observed that the Bohemian lifestyle at their Sidmouth Street lodgings was "utterly alien" to Lenin.[15] After Iskra moved again, to Geneva, in March 1903, Martov clashed with Lenin as one of the Marxists who wanted Nikolay Bauman expelled from the party on moral grounds.[16]

Martov was in exile during the strikes following Bloody Sunday, which marked the start of the 1905 Revolution.[17] From abroad, he argued that it was the role of revolutionaries to provide a militant opposition to the new bourgeois government. He advocated the joining of a network of organisations, trade unions, cooperatives, village councils and soviets, to harass the bourgeois government until the economic and social conditions made it possible for a socialist revolution to take place.

He returned to Russia in October 1905, and was arrested in February, but released in April 1906. He helped organise the RSDLP group in the First Duma and first their first declaration, which was delivered on 18 May 1906. Rearrested in July, he was deported to Finland. Later, he settled in Paris.

Martov was always to be found on the left wing of the Menshevik faction and supported reunifying with the Bolsheviks in 1905. That unity was short lived, however, and by 1907 the two factions split once again. In 1911 Martov notably wrote the pamphlet "Saviours or destroyers? Who destroyed the RSDLP and how" (Russian: "Спасители или упразднители? Кто и как разрушал"), which denounced the Bolsheviks for raising money by expropriations, among other critiques.[18] This pamphlet was denounced by both Kautsky and Lenin.

During the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, while other Mensheviks supported Russia's war effort, Martov viewed the conflict as an imperialist war. This was in line with the views of Lenin and Trotsky. The 'internationalist' minority in the Menshevik party favored a campaign for 'democratic peace'.[19] He became the central leader of the Menshevik Internationalist faction which organized in opposition to the Menshevik Party leadership. Martov also joined Trotsky in launching the newspaper Nashe Slovo ("Our Word").[20] He was the only contributor to Nashe Slovo not to align with Lenin in 1917.[21] In 1915, he sided with Lenin at an international conference in Switzerland, where he settled, but he later repudiated the Bolsheviks.[22]

Split with Lenin, Second Congress of the RSDLP (1903)

[edit]In April, prior to the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP, Martov produced a draft party programme, with which Lenin disagreed. Martov believed that RSDLP sympathizers who were willing to obey the party's leadership and recognize the party's program should be admitted as party members, as well as those people who were fully paid up party members who participated in one of party's organizations; while Lenin wanted clear dividing lines between party members and party sympathizers, with party membership being limited to those people who were fully paid up party members who participated in one of the party's organisations.[23]

When the Second Congress opened in London in August 1903, Lenin and Martov voted together on every division until the 22nd session, when a vote was taken on their respective programmes, and Lenin was outvoted by 28 to 23. At the 27th session, Lenin and Martov were again on the same side during an argument over whether the Bund should be recognised as an autonomous branch of the RSDLP, representing Jewish workers. Martov was one of the Jewish Marxist leaders (alongside Trotsky), who rejected the demands for Jewish national autonomy, with the Iskra group favouring class interests over nationalism; he was therefore deeply opposed to the Bundists' Jewish nationalism.[24] After the Bund was defeated by 41 votes to 5, its five delegates walked out. The two 'economist' delegates, Alexander Martynov and Vladimir Makhnovets also walked out, depriving Martov of seven votes, and giving Lenin's supporters a majority.[25] They referred to themselves as Bolsheviks throughout the Congress, hence their adoption of the name Bolshevik which literally means 'person of the majority'. The minority or 'Menshevik' faction adopted the corresponding title. At the end of the Congress, there was a highly emotive dispute over the future composition of the editorial board of Iskra on which Lenin proposed to exclude the three least active editors, Zasulich, Pavel Axelrod, and Alexander Potresov. Martov was shocked by his treatment of the two older Marxists, Axelrod and Zasulich, and refused to serve on the truncated board.[26]

The Congress ended in a split between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, which proved to be irreconcilable and it became permanent in 1912.[27] Martov became one of the outstanding Menshevik leaders along with Axelrod, Martynov, Fedor Dan and Irakli Tsereteli.

Personality

[edit]Martov was described as being "too good an intellectual to be a successful politician", as he often was held back by his integrity, and "philosophical approach" to matters of politics.[28] He tended to select political allies primarily by the "coherence of their general worldview", instead of "practicality" or "timeliness".[28] His "high minded approach" would later win rounds of applause among the socialist intelligentsia.[28] Nonetheless, Martov's noble principles allegedly made him too "soft" and "indecisive", at a time when the opposite were politically required of him.[29] He has been described as a "brilliant intellectual and party theoretician".[29]

Alexander Shotman, a metal worker who backed Lenin at the 2nd Congress, left a vivid description of Martov:

Martov resembled a poor Russian intellectual. His face was pale, he had sunken cheeks; his scant beard was untidy. His suit hung on him as on a clothes hanger. Manuscripts and pamphlets protruded from all his pockets. He was stooped; one of his shoulders was higher than the other. He had a stutter. His outward appearance was far from attractive, but as soon as he began a fervent speech all these outer faults seemed to vanish, and what remained was his colossal knowledge, his sharp mind, and his fanatical devotion to the cause of the working class.[30]

Trotsky, who initially supported Martov against Lenin, later described him as "one of the most talented men I have ever come across" but added: "The man's misfortune was that fate made him a politician in a time of revolution without endowing him with the necessary resources of will power."[31]

Nikolai Sukhanov, a Menshevik who worked closely with Martov in 1917, wrote:

Martov is the most intelligent man I've known ... an incomparable thinker and a remarkable analyst because of his exceptional intellect. But this intellect dominates his whole personality to such an extent that an unexpected conclusion begins to thrust itself upon you: Martov owes not only his good side to this intellect, but also his bad side, not only his highly cultivated thinking apparatus but also his weakness in action.[32]

Lenin spoke affectionately about Martov long after the split in 1903. He told Maxim Gorky "I am sorry, deeply sorry, that Martov is not with us. What a splendid comrade he is."[33] When he was ill, Lenin remarked to Krupskaya "And Martov, too, they say, is dying."[34]

The February Revolution

[edit]At the onset of the 1917 Revolution, Martov was in Zurich with Lenin.[35] He was the instigator of the idea of exchanging Russian Marxist exiles for German citizens interned in Russia. This way, the Russian Marxist revolutionary leaders, including Lenin, would manage to return to Russia following the February Revolution of 1917. However, the Provisional Government was unwilling to agree to the exchange, and Martov agreed to wait.[36] He declined to join Lenin's party on the famous sealed train which traveled across Germany. After Lenin had arrived in St Petersburg, the remaining members of the Russian colony appealed to the German government, through the Swiss Red Cross, for permission to cross, with their families. Martov was one of a party of 280 that included his Menshevik comrades, Axelrod, Martynov, and Raphael Abramovitch, who left by train on 13 May 1917.[37]

Martov reached Russia too late to prevent some Mensheviks from joining the Provisional Government. He strongly criticized those Mensheviks such as Irakli Tsereteli and Fedor Dan who, as members of the Russian government, supported the war effort. However, at a conference held on 18 June 1917, he failed to gain the support of the delegates for a policy of immediate peace negotiations with the Central Powers. He was unable to enter into an alliance with his rival Lenin to form a coalition in 1917, despite this being the "logical outcome" according to the majority of his left wing supporters in the Menshevik faction.[28]

The October Revolution

[edit]When the Bolsheviks came to power as a result of the October Revolution in 1917, Martov became politically marginalised. At the Congress of Soviets immediately after the Bolsheviks seized power, he called for a 'united democratic government' based on the parties of the soviet. His proposal was met with 'torrents of applause' in the Soviet, as the only way to avoid a civil war.[38] Martov's faction as a whole was however isolated. His view was denounced by Trotsky.[39] This is best exemplified by Trotsky's comment to him and other party members as they left the first meeting of the council of Soviets after 25 October 1917 in disgust at the way in which the Bolsheviks had seized political power: "You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on—into the dustbin of history!" [40] To this Martov replied in a moment of rage, "Then we'll leave!", and then walked in silence away without looking back. He paused at the exit, seeing a young Bolshevik worker wearing a black shirt with a broad leather belt, standing in the shadow of the portico. The young man turned on Martov with unconcealed bitterness: "And we amongst ourselves had thought, Martov would at least remain with us". Martov stopped, and with a characteristic movement, tossed up his head to emphasize his reply: "One day you will understand the crime in which you are taking part". Waving his hand wearily, he left the hall.[41]

For a while Martov led the Menshevik opposition group in the Constituent Assembly until the Bolsheviks abolished it. Later, when a factory section chose Martov as their delegate ahead of Lenin in a Soviet election, it found its supplies reduced soon afterwards.[42]

Civil war

[edit]During the Russian Civil War, Martov supported the Red Army against the White Army; however, he continued to denounce the persecution of non-violent political opponents of the Bolsheviks, whether Social Democrats, trade unionists, anarchists, or newspapers.

In one of his newspaper articles, in 1918, he argued that Stalin was unfit to hold a high position in the communist party, alleging that he had been expelled from the RSDLP for involvement in the 1907 'expropriations'. Stalin accused him of slander, and demanded that a tribunal be formed to hear the accusations, at which Martov said he would produce witnesses, but the hearing was never held because of the outbreak of civil war.[43][44]

In October 1920, Martov was given permission to legally leave Russia and go to Germany. Martov spoke at the Halle Congress of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany later that month. Martov had not intended to stay in Germany indefinitely, and only did so after the Mensheviks were outlawed in March 1921, following the Tenth Congress of the ruling Communist Party. In 1922, learning Martov was ill, Lenin asked Stalin to transfer funds to Berlin to contribute to Martov's medical care, but Stalin refused.[45] Martov died in Schömberg, Germany, in April 1923. Before his fatal illness, he launched the newspaper Socialist Courier, which remained the publication of the Mensheviks in exile in Berlin, Paris, and eventually New York until the last of them had died.

Legacy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2023) |

Martov was featured in Vladimir Mayakovsky's 1921 A Little Play About Priests Who Cannot Understand That This Is a Holiday.[46]

In the 1974 TV mini series Fall of Eagles Julius Martov was portrayed by Edward Wilson.[47]

Works

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2023) |

- The State and the Socialist Revolution (1938, New York) (1977, London), Trans. Herman Jerson

- "Short Constitution of the All-Russian Social Democratic Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies." First published in Iskra, No 58, 25 January 1904.

- "The Lesson of the Events in Russia." First published in Le Socialisme, December 29, 1907.

- "The Social Movement in Russia at the Beginning of the 20th century," 4 vols., 1909–14. ed. Julius Martov.

- "Resolution to the Second All-Russia Congress of Soviets Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies." First published in Novaya Zhizn, No. :163, October 26 (November 8), 1917, p. 3.

- "Down with the Death Penalty!" June/July 1918. First published in Yu.O. Martov (eds. S.V. Tyutyukin, O.V. Volobuev, I.Kh. Urilov),Izbrannoe, Moscow, 2000, pp. 373–383.

- "History of the Russian Social Democracy (Istoriia rossiiskoi sotsial-demokratii)." 1919. First published in German as Geschichte der russischen Sozialdemokratie, Berlin, 1926.

- What is to be done? (July 1919, Mensheviks).

- "Decomposition or Conquest of the State." 1919. First published in Mirovoi Bolshevism, Berlin 1923.

- "The Ideology of 'Sovietism'." First published in Mysl, Kharkov 1919. Originally published in English in International Review, New York 1938.

- "The Roots of World Bolshevism." Originally published in Russia in 1919.

- "The World's Social Revolution and the Aims of Social Democracy." British Labour Delegation to Russia, 1920: Report, July 1920.

- "A contradiction." British Labour Delegation to Russia, 1920: Report, July 1920.

- "The Development of Heavy Industry and the Workers' Movement in Russia (Razvitie krupnoi promyshlennosti i rabochee dvizhenie v Rossii)." 1923.

- "Notes of a Social Democrat (Zapiski sotsialdemokrata)." 1923.

- "Social and Intellectual Trends in Russia 1870–1905 (Obshchestvennye i umstvennye techeniia v Rossii 1870–1905)." 1924.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Юлий Осипович Цедербаум, IPA: [ˈjʉlʲɪj ˈosʲɪpəvʲɪtɕ tsɨdʲɪrˈbaʊm]

- ^ Russian: Юлий Осипович Мартов, IPA: [ˈmartəf]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Savel'ev, P. Iu.; Tiutiukin, S. V. (9 December 2014). "Iulii Osipovich Martov (1873–1923): The Man and the Politician". Russian Studies in History. 45 (1): 6–92. doi:10.2753/RSH1061-1983450101. ISSN 1061-1983. S2CID 153626069.

- ^ Martov, Iulii (2022). "Introduction". World Bolshevism. Translated by Kellog, Paul. p. 22.

- ^ Figes, p. 162

- ^ Shindler, Colin (2012). Israel and the European Left. New York: Continuum. p. 4.

- ^ a b c Martov, Iulii (2022). "Introduction". World Bolshevism. Translated by Kellog, Paul. Alberta: AU Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 9781771992749.

- ^ Figes, p. 147–8

- ^ Shukman, Harold (1961). The Relations Between the Jewish Bund and the RSDRP, 1897–1903 (Thesis). University of Oxford. p. 277.

(Shukman in fact states:) While Martov's contribution to the campaign against the Bund before Congress was publicly smaller than Lenin's as it consisted of only one article, in private and at the Congress he may in the long run have been the dominant figure.

- ^ Service, Robert (2010). Lenin, A Biography. London: Pan Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-330-51838-3.

- ^ Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, page 96

- ^ Krupskaya, Nadezhda (Lenin's widow) (1970). Memories of Lenin. Panther. p. 47.

- ^ Tony Cliff (1986) Lenin: Building the Party 1893–1914. London, Bookmarks: 100

- ^ Figes, p. 149

- ^ Service. Lenin. p. 149.

- ^ Krupskaya. Memories. p. 69.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1975). My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. pp. 157, 150.

- ^ Figes, p. 198

- ^ Figes, p. 180

- ^ Martov : a political biography of a Russian social democrat by Israel Getzler. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1967. ISBN 0-521-52602-7 pp117,128

- ^ Figes, p. 293

- ^ Figes, p. 294

- ^ Figes, p. 296

- ^ "Julius Martow is Dead: Russian Socialist, Enemy of Lenin, Was an Exile In Germany", The New York Times. 6 April 1923. Page 17. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Figes, p. 151

- ^ Figes, p. 82

- ^ Shapiro . The Communist Party. p. 51.

- ^ Figes, p. 153

- ^ Riches, Christopher; Palmowski, Jan (2016). "Martov, Julius (pseudonym of Yulii Osipovich Tserderbaum)". A dictionary of contemporary world history (4 ed.). [Oxford]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-180299-7. OCLC 1003235536.

- ^ a b c d Figes, p. 468

- ^ a b Figes, p. 469

- ^ Quoted in Shub, David (1966). Lenin: A Biography. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 78.

- ^ Trotsky. My Life. p. 253.

- ^ Sukhanov, N.N. (1962). The Russian Revolution 1917, Eyewitness Account. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 354–55.

- ^ Gorky, Maxim (n.d.). Days With Lenin. London: Martin Lawrence. p. 54.

- ^ Shub. Lenin. p. 418.

- ^ Figes, p. 323

- ^ Figes, p. 385

- ^ Abramovitch, Raphael (1962). The Soviet Revolution. New York: International Universities Press. p. 26.

- ^ Figes, p. 489

- ^ Figes, p. 490

- ^ Trotsky, Leon The History of the Russian Revolution p. 1156

- ^ I henhold til Boris Ivanovich Nicolaevsky erindringer "Pages from the Past"

- ^ Martov : a political biography of a Russian social democrat by Israel Getzler. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1967. ISBN 0-521-52602-7

- ^ Radzinsky, Edvard (1997). Stalin. London: Hodder and Stroughton. p. 61. ISBN 0-340-68046-6.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1940). "Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence Chapter 4". Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Service, Robert (2005). Stalin: A Biography. Harvard University Press. p. 156.

- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (1 May 1979). "A Little Play About Priests Who Cannot Understand That This Is a Holiday". Theater. 10 (2). Duke University Press: 72–75. doi:10.1215/00440167-10-2-72.

- ^ Fall of Eagles (TV Mini Series 1974) - IMDb. Retrieved 4 September 2024 – via www.imdb.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Figes, Orlando. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924 (2017).

- Getzler, Israel. Martov: A Political Biography of a Russian Social Democrat (2003).

- Savel'ev, P. Iu.; Tiutiukin, S. V. (2006). "Iulii Osipovich Martov (1873–1923): The Man and the Politician". Russian Studies in History. 45 (1): 6–92. doi:10.2753/RSH1061-1983450101. S2CID 153626069. Translation of the 1995 Russian original.

- Haimson, Leopold H., Ziva Galili and Richard Wortman, The Making of Three Russian Revolutionaries: Voices from the Menshevik Past (Cambridge and Paris, 1987).

External links

[edit]- 1873 births

- 1923 deaths

- Members of the Central Committee of the 1st Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

- Candidates of the Central Committee of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

- Politicians from Istanbul

- European democratic socialists

- Mensheviks

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution

- Russian socialists

- Jewish socialists