Elza Soares

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Portuguese. (June 2020) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Elza Soares | |

|---|---|

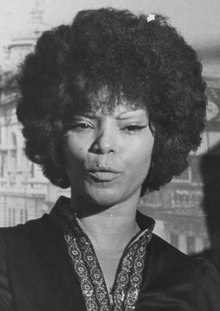

Soares in 1971 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Elza Gomes da Conceição |

| Born | 23 June 1930 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Died | 20 January 2022 (aged 91) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

| Genres | |

| Occupation | Singer |

| Years active | 1950–2022 |

| Labels | Odeon |

Elza da Conceição Soares (née Gomes; 23 June 1930 – 20 January 2022), known professionally as Elza Soares (Brazilian Portuguese: [ˈɛwzɐ ˈswaɾis]), was a Brazilian samba singer. In 1999, she was named Singer of the Millennium along with Tina Turner by BBC Radio.[1]

Elza was deemed dangerous by the Military dictatorship in Brazil (1964–1985), and in 1970 her house in the Jardim Botânico neighborhood, in Rio de Janeiro, was machine-gunned by regime agents. Inside were her partner Garrincha and their children. The living room, where the young children were, was destroyed by the blasts. She and Garrincha had to flee to Italy, where they were received by Chico Buarque de Hollanda also in exile.[2][3][4]

Biography

[edit]Elza Gomes da Conceição was born on 23 June 1930 in Padre Miguel, Rio de Janeiro.[5] Her father Avelino Gomes was a factory worker and guitarist, and her mother Rosária Maria da Conceição was a washerwoman. She was born in the Moça Bonita, a favela in the Padre Miguel neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. During her childhood, Soares played on the streets, spun wooden tops, flew kites, and fought with boys. Despite poverty and having to carry buckets of water on her head, she had a happy childhood. When she was 12, she was forced by her father to marry Lourdes Antônio Soares, also known as Alaúrdes, and within a year later gave birth to her first child, João Carlos. Soares liked to sing, and when she needed money for medicine for her son, she participated in a vocal contest presented by Ary Barroso at Rádio Tupi. She was given money for participating and was then able to buy the medicine. When she was fifteen, she gave birth to her second child, who died. After her husband became ill with tuberculosis, she began working at the Veritas soap factory in the Engenho de Dentro neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. At twenty-one she was a widow, left alone to raise her children: four boys and one girl. She dreamed of becoming a singer.

When she was thirty-two she had a relationship with football player Garrincha. She was vilified by Brazilian society, with many accusing her of breaking up his marriage. She was shouted at in the street, received death threats, and her house was pelted with eggs and tomatoes. On 13 April 1969 her mother died in a car accident. Garrincha, Soares, and her daughter Sara were also injured in this accident. Garrincha was driving drunk on Presidente Dutra highway when a truck merged into the lane. Everyone in the car was hurt, and Dona Rosário was thrown from the vehicle and killed. Soares and Garrincha remained married for sixteen years (1968–1982). Garrincha's friends did not accept Soares as his wife, instead calling her a "witch." Soares tried to curb her husband's dependence on alcohol by visiting bars and pleading with them not to serve her husband. The couple had one child, a boy, born in 1976. He was named after his father, Manuel Francisco dos Santos, and received the nickname Garrincha Jr. In 1983 Garrincha died of cirrhosis, which devastated Soares, though they were already separated.

On 11 January 1986, her son died when he was 9 years old in a car accident as he was coming back from visiting his father's hometown, Magé. It had been raining and the driver lost control of the vehicle. The door opened and the boy was thrown into the Imbariê River. Soares was disconsolate and considered ending her own life. She left Brazil and toured Europe and the United States.

After many years of searching for her long lost daughter, they were reunited after Soares returned to Brazil. On 26 July 2015 Soares lost her fifth son, Gerson, when he was 59 years old. He died of complications of a urinary tract infection. Soares had six children: João Carlos, Gerson, Gilson, Dilma, Sara, and Garrincha. She died at her residence in Rio de Janeiro, on 20 January 2022, at the age of 91.[5]

Career

[edit]In 1958, Soares spent eight months touring Argentina with Mercedes Batista.[6] She became popular with her first single "Se Acaso Você Chegasse", on which she introduced scat singing à la Louis Armstrong, adding a bit of jazz to samba, however, Elza said that she did not know American music at the time.[7] She moved to São Paulo, where she performed at theaters and night clubs. Her husky voice became her trademark. After finishing her second album, A Bossa Negra, she went to Chile to represent Brazil in the 1962 FIFA World Cup and met Louis Armstrong.

From 1967 to 1969, Soares recorded three albums with the record label Odeon, partnering with singer Miltinho. The albums were titled Elza, Miltinho e Samba (Volumes 1–3). The songs in these albums were mostly in the potpourri style with duets. The albums were produced by Milton Miranda and Hermínio Bello de Carvalho and re-released on CD in 2003 by EMI-Odeon.

In the 1970s, she toured the U.S. and Europe. In 2000, she was named Best Singer of the Millennium by the BBC in London, where she performed a concert with Gal Costa, Chico Buarque, Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, and Virgínia Rodrigues. During the same year, she played a series of avant-garde concerts directed by José Miguel Wisnik in Rio de Janeiro.

Soares scored a number of hits in Brazil throughout her career, including "Se Acaso Você Chegasse" (1960), "Boato" (1961), "Cadeira Vazia" (1961), "Só Danço Samba" (1963), "Mulata Assanhada" (1965), and "Aquarela Brasileira" (1974). Elza Pede Passagem produced no major hit singles but it was considered representative of the samba-soul of the early 1970s.

In 2002, her album Do Cóccix Até O Pescoço album earned a Grammy nomination. The album was recorded with Caetano Veloso, Chico Buarque, Carlinhos Brown, and Jorge Ben Jor. In 2004, Soares released Vivo Feliz with the single, "Rio de Janeiro", a homage to her city of birth. While not as successful in sales as her previous release, the album carried on the theme of mixing samba and bossa nova with modern electronic music and effects. The album included collaborations with Nando Reis, Fred 04 (former leader of mangue beat band Mundo Livre S/A), and Zé Keti.

In 2007, she was invited to sing a cappella the Brazilian National Anthem at the opening ceremony of the 2007 Pan American Games.

Soares joined Jair Rodrigues and Seu Jorge for Sambistas (2009). In 2016, A Mulher do Fim do Mundo was released internationally with the translated title Woman at the End of the World.[8] She also performed at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, where she sang "O Canto de Ossanha" by Baden Powell and Vinicius de Moraes.

Her album A Mulher do Fim do Mundo was released in 2015. It was praised by critics as one of the best MPB albums of the past years. She won the award for Best Album in pop/rock/reggae/hip-hop/funk. This album was also nominated for Best Album of Brazilian Popular Music and Best Song in Portuguese at the 17th edition of the Latin Grammy Awards.

Her album Deus É Mulher was ranked as the 2nd best Brazilian album of 2018 by the Brazilian edition of Rolling Stone magazine[9] and among the 25 best Brazilian albums of the first half of 2018 by the São Paulo Association of Art Critics.[10]

The follow-up Planet Fome was considered one of the 25 best Brazilian albums of the second half of 2019 by the São Paulo Association of Art Critics.[11] For this album, she planned a cover of "Comida", by Titãs featuring the then current members of the band (Branco Mello, Sérgio Britto and Tony Bellotto), but she ended up choosing to save the song for later and it was released in October 2020 to mark the album's first anniversary and to celebrate its nomination for the Latin Grammy Award.[12][13][14]

Discography

[edit]

- Se Acaso Você Chegasse (Odeon, 1960)[15]

- A Bossa Negra (Odeon, 1961/Universal 2003)

- O Samba é Elza Soares (Odeon, 1961)

- Sambossa (Odeon, 1963)

- Na Roda do Samba (Odeon, 1964)

- Um Show de Elza (Odeon, 1965)

- Com A Bola Branca (Odeon, 1966)

- O Máximo em Samba (Odeon, 1967)

- Elza, Miltinho e Samba (Odeon, 1967)

- Elza, Miltinho e Samba Vol.2 (Odeon, 1968)

- Elza Soares e Wilson das Neves (Odeon, 1968)

- Elza, Carnaval & Samba (Odeon, 1969)

- Elza, Miltinho e Samba Vol.3 (Odeon, 1969)

- Samba & Mais Sambas (Odeon, 1969)

- Elza Pede Passagem (Odeon, 1972/EMI, 2004)

- Sangue, Suor e Raça (Odeon, 1972)

- Aquarela Brasileira (Odeon, 1973)

- Elza Soares (Tapecar, 1974)

- Nos Braços do Samba (Tapecar, 1974)

- Lição De Vida (Tapecar, 1976)

- Pilão + Raça = Elza (Tapecar, 1977)

- Senhora da Terra (CBS, 1979)

- Elza Negra, Negra Elza (CBS, 1980)

- Somos Todos Iguais (Som Livre, 1985)

- Voltei (RGE, 1988)

- Trajetória (Universal Music, 1997)

- Carioca da Gema (1999)

- Do Cóccix Até O Pescoço (Maianga/Tratore, 2002)

- Vivo Feliz (Tratore, 2004)

- Beba-Me (Biscoito Fino, 2007)

- A Mulher do Fim do Mundo (Circus, 2015)

- Elza Canta e Chora Lupi (2016)

- Deus é Mulher (Deckdisc, 2018)[16]

- Planeta Fome (Deckdisc, 2019)

- Elza Soares & João de Aquino (Deckdisc, 2021)

- No tempo da intolerância (Deck, 2023)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schnabel, Tom (24 June 2011). "Artists You Should Know: (Elza Soares) Tina Turner, You've Met Your Brazilian Match". KCRW. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021.

- ^ Soares, Elza (25 May 2014). "A Copa que não comemorei" [The World Cup I didn't celebrate]. Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Rodrigues, Henrique (20 January 2022). "Elza, a voz contra o autoritarismo: Da casa fuzilada na Ditadura ao 'Fora, Bolsonaro'" [Elza, the voice against authoritarianism: From the house shot at during the dictatorship to 'Out, Bolsonaro']. Revista Forum (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 6 July 2024. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Elza Soares recebe diploma de Embaixadora da Música que MIS lhe dera há 2 anos" [Elza Soares receives the Music Ambassador diploma that MIS gave her 2 years ago]. Jornal do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). No. 1. 21 December 1971. p. 25. OCLC 1754340. Retrieved 30 December 2024 – via Google Books.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Astor, Michael (21 January 2022). "Elza Soares, Who Pushed the Boundaries of Brazilian Music, Dies at 91". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Brabo, Tânia Suely Antonelli Marcelino (23 December 2020). Mulheres, gênero e sexualidades na sociedade: diversos olhares sobre a cultura da desigualdade [Women, gender and sexualities in society: different perspectives on the culture of inequality] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 2. Editora Oficina Universitária. p. 156. ISBN 978-65-86546-86-6.

- ^ Soares, Elza (2 September 2002). "Elza Soares" (Interview) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Interviewed by Paulo Markun. São Paulo Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016 – via Roda Viva.

- ^ Mercer, Michelle. "Music Review: 'Woman At The End Of The World,' Elza Soares". NPR.org. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Antunes, Pedro (21 December 2018). "Rolling Stone Brasil: os 50 melhores discos nacionais de 2018". Rolling Stone Brasil (in Portuguese). Grupo Perfil. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Antunes, Pedro (30 November 2018). "Baco Exu do Blues, Gilberto Gil, Duda Beat: os 25 melhores discos brasileiros do segundo semestre de 2018, segundo a APCA". Rolling Stone Brasil (in Portuguese). Grupo Perfil. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Antunes, Pedro (7 December 2019). "Os 25 melhores discos brasileiros do 2º semestre de 2019, segundo a APCA [LISTA]". Rolling Stone Brasil (in Portuguese). Grupo Perfil. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Elza Soares e Titãs lançam clipe da música 'Comida'". IstoÉ. Editora Três. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Ferreira, Mauro (25 October 2020). "Elza Soares requenta 'Comida' com Titãs em fogo brando". G1. Grupo Globo. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Reis, Yolanda (23 October 2020). "Elza Soares entrevista Titãs, Titãs entrevistam Elza Soares - e, juntos, lançam clipe para 'Comida' [EXCLUSIVO]". Rolling Stone Brasil. Grupo Perfil. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Leão, Renata (February 2006). "Aqui e agora". TPM (in Portuguese): 16–23.

- ^ "Elza Soares – Deus É Mulher | Deckdisc". deckdisc.com.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 22 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- Elza Soares discography at Discogs

- Elza Soares at IMDb

- 1930 births

- 2022 deaths

- 20th-century Brazilian women singers

- 20th-century Brazilian singers

- 21st-century Brazilian women singers

- 21st-century Brazilian singers

- Afro-Brazilian women singers

- Brazilian bossa nova singers

- Música Popular Brasileira singers

- Singers from Rio de Janeiro (city)

- Samba musicians

- Latin Grammy Award winners

- Women in Latin music

- Portuguese-language singers of Brazil

- Multishow Brazilian Music Award winners