Yolk sac

| Yolk sac | |

|---|---|

Human embryo of 3.6 mm | |

Human embryo from thirty-one to thirty-four days | |

| Details | |

| Carnegie stage | 5b |

| Days | 9 |

| Precursor | Endoderm |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesicula umbilicalis; saccus vitellinus |

| MeSH | D015017 |

| TE | sac_by_E5.7.1.0.0.0.4 E5.7.1.0.0.0.4 |

| FMA | 87180 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though yolk sac is far more widely used. In humans, the yolk sac is important in early embryonic blood supply,[1] and much of it is incorporated into the primordial gut during the fourth week of embryonic development.[2]

In humans

[edit]

The yolk sac is the first element seen within the gestational sac during pregnancy,[1] usually at 3 days gestation.

The yolk sac is situated on the front (ventral) part of the embryo; it is lined by extra-embryonic endoderm,[3] outside of which is a layer of extra-embryonic mesenchyme, derived from the epiblast.

Blood is conveyed to the wall of the yolk sac by the primitive aorta and after circulating through a wide-meshed capillary plexus, is returned by the vitelline veins to the tubular heart of the embryo. This constitutes the vitelline circulation, which in humans serves as a location of haematopoiesis.[4][5] Before the placenta is formed and can take over, the yolk sac provides nutrition and gas exchange between the mother and the developing embryo.[6]

At the end of the fourth week, the yolk sac presents the appearance of a small pear-shaped opening (traditionally called the umbilical vesicle), into the digestive tube by a long narrow tube, the vitelline duct. Rarely, the yolk sac can be seen in the afterbirth as a small, somewhat oval-shaped body whose diameter varies from 1 mm to 5 mm; it is situated between the amnion and the chorion and may lie on or at a varying distance from the placenta. There is no clinical significance to a residual external yolk sac.

-

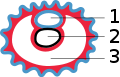

Diagram showing earliest observed stage of human ovum.

1 - Amniotic cavity

2 - Yolk-sac

3 - Chorion -

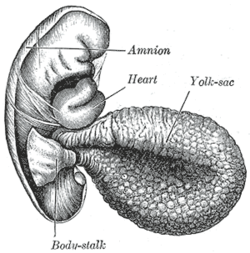

Diagram illustrating early formation of allantois and differentiation of body-stalk.

1 Amniotic cavity

2 Body-stalk

3 Allantois

4 Yolk-sac

5 Chorion -

Diagram showing later stage of allantoic development with commencing constriction of the yolk-sac.

1 Heart

2 Amniotic cavity

3 Embryo

4 Body-stalk

5 Placental villi

6 Allantois

7 Yolk-sac

8 Chorion -

Diagram illustrating a later stage in the development of the umbilical cord.

1 Placental villi

2 Yolk-sac

3 Umbilical cord

4 Allantois

5 Heart

6 Digestive tube

7 Embryo

8 Amniotic cavity

As a rule the duct undergoes complete obliteration by the 20th week as most of the yolk sac is incorporated into the developing gastrointestinal tract, but in about two percent of cases its proximal part persists as a diverticulum from the small intestine, Meckel's diverticulum, which is situated about 60 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve, and may be attached by a fibrous cord to the abdominal wall at the umbilicus.

Sometimes a narrowing of the lumen of the ileum is seen opposite the site of attachment of the duct.

Histogenesis

[edit]The yolk sac starts forming during the second week of the embryonic development, at the same time as the shaping of the amniotic sac. The hypoblast starts proliferating laterally and descending. In the meantime Heuser's membrane, located on the opposite pole of the developing vesicle, starts its upward proliferation and meets the hypoblast.

Modifications

[edit]- Primary yolk sac: it is the vesicle which develops in the second week, its floor is represented by Heuser's membrane and its ceiling by the hypoblast. It is also known as the exocoelomic cavity.

- Secondary yolk sac: this structure is formed when the extraembryonic mesoderm separates to form the extraembryonic coelom; cells from the mesoderm pinch off an area of the yolk sac,[3] and what remains is the secondary yolk sac.

- The final yolk sac: during the fourth week of development, during organogenesis, part of the yolk sac is surrounded by endoderm and incorporated into the embryo as the gut. The remaining part of the yolk sac is the final yolk sac.

Additional images

[edit]-

Surface view of embryo of Hylobates concolor (a gibbon).

-

Human embryo—length, 2 mm. Dorsal view, with the amnion laid open. X 30.

-

Dorsum of human embryo, 2.11 mm in length.

-

Section through the embryo.

-

Fetus of about eight weeks, enclosed in the amnion. Magnified a little over two diameters.

-

Model of human embryo 1.3 mm long.

-

Section through ovum imbedded in the uterine decidua

-

Human embryo about fifteen days old. Brain and heart represented from right side. Digestive tube and yolk sac in median section.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Goh, Issac; et al. (18 August 2023). "Yolk sac cell atlas reveals multiorgan functions during human early development". Science. 381 (6659). doi:10.1126/science.add7564. PMC 7614978.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lutfey, Karen; Freese, Jeremy (2005). "Toward Some Fundamentals of Fundamental Causality: Socioeconomic Status and Health in the Routine Clinic Visit for Diabetes". American Journal of Sociology. 110 (5): 1326–1372. doi:10.1086/428914. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 10.1086/428914. S2CID 17629087.

- ^ The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Anatomy: Chapter 7

- ^ a b Hafez, S. (2017-01-01), Huckle, William R. (ed.), "Chapter One - Comparative Placental Anatomy: Divergent Structures Serving a Common Purpose", Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, Molecular Biology of Placental Development and Disease, 145, Academic Press: 1–28, doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2016.12.001, PMID 28110748, retrieved 2020-10-21

- ^ Moore, Keith; Persaud, TVN; Torchia, Mark (2013). The Developing Human. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-2002-0.

- ^ Blaas, Harm-Gerd K; Carrera, José M (2009-01-01), Wladimiroff, Juriy W; Eik-Nes, Sturla H (eds.), "Chapter 4 - Investigation of early pregnancy", Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Edinburgh: Elsevier, pp. 57–78, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-51829-3.00004-0, ISBN 978-0-444-51829-3, retrieved 2020-10-21

- ^ Donovan, Mary F.; Bordoni, Bruno (2020), "Embryology, Yolk Sac", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32310425, retrieved 2020-09-11