TAR DNA-binding protein 43: Difference between revisions

Rachmanichou (talk | contribs) →Structure: Added a summary of TDP-43's structure. Feel free to make comments and to edit of course, I am by no means an expert in this field, but I felt like this page needed a little lift. |

Rachmanichou (talk | contribs) →The N-Terminal Domain (NTD) [1, 76][27]:: As for the reference to solenoid structure, I am not exactly sure if the solenoid-like structure of this domain refers to this exact term. |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

=== Structure recapitulation: === |

=== Structure recapitulation: === |

||

TDP-43 is a 414 |

TDP-43 is a 414 [[Amino acid|amino acids]] long, 43 kDa heavy [[protein]]. From [[N-terminus|N-term]] to [[C-terminus|C-term]] one can delimit (note that strict amino acid delimitation of different domains differs from a source to another of a few amino acids):<sup>[5]</sup> |

||

==== The N-Terminal Domain (NTD) [1, 76]<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Qin|first=Haina|last2=Lim|first2=Liang-Zhong|last3=Wei|first3=Yuanyuan|last4=Song|first4=Jianxing|date=2014-12-30|title=TDP-43 N terminus encodes a novel ubiquitin-like fold and its unfolded form in equilibrium that can be shifted by binding to ssDNA|url=http://www.pnas.org/lookup/doi/10.1073/pnas.1413994112|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|language=en|volume=111|issue=52|pages=18619–18624|doi=10.1073/pnas.1413994112|issn=0027-8424|pmc=PMC4284588|pmid=25503365}}</ref>: ==== |

|||

==== The N-Terminal Domain (NTD) [1, 76]<sup>[27]</sup>: ==== |

|||

The NTD is first known for being a keystone of TDP-43 polymerization. Indeed, dimers are formed by head-to-head interactions between NTDs, and the polymer thus obtained allows for pre-mRNA splicing.< |

The NTD is first known for being a keystone of TDP-43 [[polymerization]]. Indeed, dimers are formed by head-to-head interactions between NTDs, and the polymer thus obtained allows for [[Primary transcript|pre-mRNA]] [[Splicing quantitative trait loci|splicing]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Prasad|first=Archana|last2=Bharathi|first2=Vidhya|last3=Sivalingam|first3=Vishwanath|last4=Girdhar|first4=Amandeep|last5=Patel|first5=Basant K.|date=2019-02-14|title=Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis|url=https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00025/full|journal=Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience|volume=12|pages=25|doi=10.3389/fnmol.2019.00025|issn=1662-5099|pmc=PMC6382748|pmid=30837838}}</ref> However, further oligomerization brings to more toxic accumulates. This process of polymerization into dimers, larger forms or just stabilizing monomers is dependent on TDP-43 conformational equilibrium between monomers, homodimers and oligomers. Hence, in diseased [[Cell (biology)|cells]], TDP-43 is overexpressed and this leads to a NTD showing high propensity to aggregate. Contrary to this, in normal cells, normal levels of TDP-43 allow for folded NTD, preventing aggregates and polymers formation. |

||

More recently, this domain was found to have a ubiquitin-like structure. It bears 27,6% of homology with Ubiquitin-1 and a |

More recently, this domain was found to have a ubiquitin-like structure. It bears 27,6% of homology with [[Ubiquitin ligase|Ubiquitin-1]] and a [[Beta sheet|β]]1-β2-[[Alpha helix|α]]1-β3-β4-β5-β6 + 2*[[Sulfate|SO<sub>4</sub><sup>2-</sup>]] form<ref>{{Cite web|title=TARDBP TAR DNA binding protein [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/23435|access-date=2021-12-13|website=www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov}}</ref>. Ubiquitin-like domain are usually associated with a greater affinity for [[RNA]]/[[DNA]]. However, in the unique case of TDP-43, the Ubiquitin-like NTD binds directly to [[Ssdna|ssDNA]]. This interaction permits the conformational equilibrium cited higher to shift towards non-aggregated forms<sup>[6]</sup>. |

||

The domain spanning from [1,80] has a solenoid-like structure which sterically gaps aggregation prone C-term region< |

The domain spanning from [1,80] has a [[Solenoid protein domain|solenoid]]-like structure which sterically gaps aggregation prone C-term region<ref name=":0" />. |

||

All of this raises the possibility that NTD and the RNA Recognition Motifs (later on defined) could cooperatively interact with nucleic acids to accomplish TDP-43’s physiological functions<sup>[7]</sup>. |

All of this raises the possibility that NTD and the [[RNA recognition motif|RNA Recognition Motifs]] (later on defined) could cooperatively interact with nucleic acids to accomplish TDP-43’s physiological functions<sup>[7]</sup>. |

||

==== [[Mitochondrion|Mitochondrial]] Localization Signal:<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Huang|first=Chunhui|last2=Yan|first2=Sen|last3=Zhang|first3=Zaijun|date=2020-12|title=Maintaining the balance of TDP-43, mitochondria, and autophagy: a promising therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases|url=https://translationalneurodegeneration.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40035-020-00219-w|journal=Translational Neurodegeneration|language=en|volume=9|issue=1|pages=40|doi=10.1186/s40035-020-00219-w|issn=2047-9158|pmc=PMC7597011|pmid=33126923}}</ref> ==== |

|||

==== Mitochondrial Localization Signal:<sup>[8]</sup> ==== |

|||

There are six M to be accounted on TDP-43’s amino acid sequence, although only M1, M3, and M5 were shown to be essential for M localization. Indeed, their ablation leads to a lessened mitochondrial localization. |

There are six M to be accounted on TDP-43’s amino acid sequence, although only M1, M3, and M5 were shown to be essential for M localization. Indeed, their ablation leads to a lessened mitochondrial localization. |

||

These localizing sequences are found on the following amino acids: |

These localizing sequences are found on the following amino acids: |

||

M1: [35, 41], M2: [105, 112], M3: [146-150], M4: [228, 235], M5: [294, 300], M6: [228, 236] |

M1: [35, 41], M2: [105, 112], M3: [146-150], M4: [228, 235], M5: [294, 300], M6: [228, 236]. |

||

==== Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS), [82, 98]: ==== |

==== Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS), [82, 98]: ==== |

||

This domain is of critical importance in ALS, and such is witnessed by the depletion or the mutations (notably A90V) of this domain, which cause loss-of-function from nucleus and promote aggregating, two processes very likely to conduct to TDP-43’s toxic gain of function<sup>[2]</sup>. |

This domain is of critical importance in [[Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis|ALS]], and such is witnessed by the depletion or the mutations (notably A90V) of this domain, which cause loss-of-function from nucleus and promote aggregating, two processes very likely to conduct to TDP-43’s toxic gain of function<sup>[2]</sup>. |

||

It is thereby of the utmost importance to note that TDP-43’s nuclear localization is absolutely critical for it to fulfill its physiological functions. |

It is thereby of the utmost importance to note that TDP-43’s nuclear localization is absolutely critical for it to fulfill its physiological functions<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Ratti|first=Antonia|last2=Buratti|first2=Emanuele|date=2016-08|title=Physiological functions and pathobiology of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS proteins|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jnc.13625|journal=Journal of Neurochemistry|language=en|volume=138|pages=95–111|doi=10.1111/jnc.13625}}</ref>. |

||

==== RNA Recognition Motif 1 (RRM1), [105, 181] |

==== [[RNA recognition motif|RNA Recognition Motif]] 1 (RRM1), [105, 181]: ==== |

||

Much like many hnRNPs, TDP-43’s RRMs encompass highly conserved motifs of primary importance for fulfilling their function. Both RRMs follow this pattern: β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4-β5, which allows them to bind to both RNA and DNA onto UG/TG-repeats of 3’UTR (Untranslated Terminal Regions) end of mRNA/DNA. |

Much like many hnRNPs, TDP-43’s RRMs encompass highly conserved motifs of primary importance for fulfilling their function. Both RRMs follow this pattern: β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4-β5<ref name=":0" />, which allows them to bind to both RNA and DNA onto UG/TG-repeats of [[Three prime untranslated region|3’UTR]] (Untranslated Terminal Regions) end of [[Messenger RNA|mRNA]]/DNA<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Qin|first=Haina|last2=Lim|first2=Liang-Zhong|last3=Wei|first3=Yuanyuan|last4=Song|first4=Jianxing|date=2014-12-30|title=TDP-43 N terminus encodes a novel ubiquitin-like fold and its unfolded form in equilibrium that can be shifted by binding to ssDNA|url=http://www.pnas.org/lookup/doi/10.1073/pnas.1413994112|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|language=en|volume=111|issue=52|pages=18619–18624|doi=10.1073/pnas.1413994112|issn=0027-8424|pmc=PMC4284588|pmid=25503365}}</ref>. |

||

These sequences mainly ensure mRNA processing, RNA export and RNA stabilizing. It is notaby thanks to these sequences that TDP-43 importantly binds to its own mRNA regulats its very own solubility and polymerization. |

These sequences mainly ensure mRNA processing, [[RNA|RNA export]] and RNA stabilizing. It is notaby thanks to these sequences that TDP-43 importantly binds to its own mRNA regulats its very own solubility and polymerization. |

||

==== RRM2 [191, 261]: ==== |

==== RRM2 [191, 261]: ==== |

||

In pathological conditions, it notably binds to [[NF-κB|p65/NF-kB]], an apoptosis implicated factor, and is thus a potential therapeutic target. Moreover it can be burdened with a mutation, D169G, altering a key cleaving site for regulating formation of toxic inclusions<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Pozzi|first=Silvia|last2=Thammisetty|first2=Sai Sampath|last3=Codron|first3=Philippe|last4=Rahimian|first4=Reza|last5=Plourde|first5=Karine Valérie|last6=Soucy|first6=Geneviève|last7=Bareil|first7=Christine|last8=Phaneuf|first8=Daniel|last9=Kriz|first9=Jasna|last10=Gravel|first10=Claude|last11=Julien|first11=Jean-Pierre|date=2019-02-25|title=Virus-mediated delivery of antibody targeting TAR DNA-binding protein-43 mitigates associated neuropathology|url=https://www.jci.org/articles/view/123931|journal=Journal of Clinical Investigation|language=en|volume=129|issue=4|pages=1581–1595|doi=10.1172/JCI123931|issn=0021-9738}}</ref>. |

|||

This second recognition motif bears a supplementary role in maintaining physiological conformational equilibrium because of its ability to bind to ssRNA, ssDNA and dsDNA. Thus, it allows to keep high solubility and to prevent aggregating. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In pathological conditions, it notably binds to p65/NF-kB, an apoptosis implicated factor, and is thus a potential therapeutic target. Moreover it can be burdened with a mutation, D169G, altering a key cleaving site for regulating formation of toxic inclusions<sup>[9]</sup>. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

This sequence probably bears a role in TDP-43’s shuttling function, and was recently found using a prediction algorithm<sup>[10]</sup>. |

This sequence probably bears a role in TDP-43’s shuttling function, and was recently found using a prediction algorithm<sup>[10]</sup>. |

||

==== Disordered Glycin Rich C-terminal domain (CTD), [277, 414]: ==== |

==== Disordered Glycin Rich C-terminal domain (CTD), [277, 414]: ==== |

||

Much like 70 other RNA binding proteins, TDP-43 bears a Q/N rich domain [344, 366] which resembles yeast prion sequence. This sequence is called a Prion-Like Domain (PLD). |

Much like 70 other RNA binding proteins, TDP-43 bears a [[Glutamine|Q]]/[[Asparagine|N]] rich domain [344, 366] which resembles [[yeast]] [[prion]] sequence. This sequence is called a Prion-Like Domain (PLD).<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Nonaka|first=Takashi|last2=Masuda-Suzukake|first2=Masami|last3=Arai|first3=Tetsuaki|last4=Hasegawa|first4=Yoko|last5=Akatsu|first5=Hiroyasu|last6=Obi|first6=Tomokazu|last7=Yoshida|first7=Mari|last8=Murayama|first8=Shigeo|last9=Mann|first9=David M.A.|last10=Akiyama|first10=Haruhiko|last11=Hasegawa|first11=Masato|date=2013-07|title=Prion-like Properties of Pathological TDP-43 Aggregates from Diseased Brains|url=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211124713002854|journal=Cell Reports|language=en|volume=4|issue=1|pages=124–134|doi=10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.007}}</ref> |

||

PLDs are low complexity sequences that have been reported to mediate gene regulation via Liquid-Liquid Phase Transition (LLP) thus driving RNP granule assembly< |

PLDs are low complexity sequences that have been reported to mediate gene regulation via Liquid-Liquid Phase Transition (LLP) thus driving RNP granule assembly<ref name=":0" /> . Forming these microscopically visible [[Ribonucleoprotein particle|RNP]] granules is thought to induce more effective gene regulatory process<ref>{{Citation|last=Fan|first=Alexander C.|title=RNA Granules and Diseases: A Case Study of Stress Granules in ALS and FTLD|date=2016|url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-29073-7_11|work=RNA Processing|volume=907|pages=263–296|editor-last=Yeo|editor-first=Gene W.|place=Cham|publisher=Springer International Publishing|doi=10.1007/978-3-319-29073-7_11|isbn=978-3-319-29071-3|pmc=PMC5247449|pmid=27256390|access-date=2021-12-13|last2=Leung|first2=Anthony K. L.}}</ref>. |

||

It is here noted that LLP are reversible phenomenons of de-mixing a solution into two distinct liquid phases, hereby forming granules. |

It is here noted that LLP are reversible phenomenons of de-mixing a solution into two distinct liquid phases, hereby forming granules. |

||

| Line 55: | Line 53: | ||

This CTD is often reported to play important role in pathogenic behavior of TDP-43: |

This CTD is often reported to play important role in pathogenic behavior of TDP-43: |

||

RNPs granules could also have a role in stress response, and thus, aging, or persistance stress could lead the LLPs to turn into irreversible |

[[Ribonucleoprotein particle|RNPs]] granules could also have a role in stress response, and thus, aging, or persistance stress could lead the LLPs to turn into irreversible Liquid Solid Phase sepration, pathological aggregates notably found in [[Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis|ALS]] neurons<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hennig|first=Sven|last2=Kong|first2=Geraldine|last3=Mannen|first3=Taro|last4=Sadowska|first4=Agata|last5=Kobelke|first5=Simon|last6=Blythe|first6=Amanda|last7=Knott|first7=Gavin J.|last8=Iyer|first8=K. Swaminathan|last9=Ho|first9=Diwei|last10=Newcombe|first10=Estella A.|last11=Hosoki|first11=Kana|date=2015-08-17|title=Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles|url=https://rupress.org/jcb/article/210/4/529/38290/Prionlike-domains-in-RNA-binding-proteins-are|journal=Journal of Cell Biology|language=en|volume=210|issue=4|pages=529–539|doi=10.1083/jcb.201504117|issn=0021-9525|pmc=PMC4539981|pmid=26283796}}</ref>. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

However, notice is to be taken that some points are not always consensual. Indeed, due to its hydrophobic structure, TDP-43 can be hard to analyze, and parts of it remain somewhat vague. Precise sites of phosphorylation, methylation, or even binding are still a bit elusive< |

However, notice is to be taken that some points are not always consensual. Indeed, due to its [[Hydrophobe|hydrophobic]] structure, TDP-43 can be hard to analyze, and parts of it remain somewhat vague. Precise sites of [[phosphorylation]], [[methylation]], or even binding are still a bit elusive<ref name=":0" />. |

||

== Function == |

== Function == |

||

Revision as of 23:34, 13 December 2021

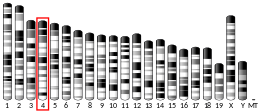

TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43, transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TARDBP gene.[5]

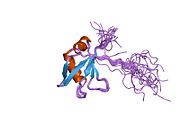

Structure

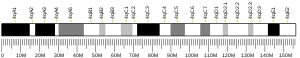

TDP-43 is 414 amino acid residues long. It consists of 4 domains: an N-terminal domain spanning residues 1-76 (NTD) with a well-defined fold that has been shown to form a dimer or oligomer;[6][7] 2 highly conserved folded RNA recognition motifs spanning residues 106-176 (RRM1) and 191-259 (RRM2), respectively, required to bind target RNA and DNA;[8] an unstructured C-terminal domain encompassing residues 274-414 (CTD), which contains a glycine-rich region, is involved in protein-protein interactions, and harbors most of the mutations associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[9]

The entire protein devoid of large solubilising tags has been purified.[10] The full-length protein is a dimer.[10] The dimer is formed due to a self-interaction between two NTD domains,[6][7] where the dimerisation can be propagated to form higher-order oligomers.[6]

The protein sequence also has a nuclear localization signal (NLS, residues 82–98), a former nuclear export signal (NES residues 239–250) and 3 putative caspase-3 cleavage sites (residues 13, 89, 219).[10]

Structure recapitulation:

TDP-43 is a 414 amino acids long, 43 kDa heavy protein. From N-term to C-term one can delimit (note that strict amino acid delimitation of different domains differs from a source to another of a few amino acids):[5]

The N-Terminal Domain (NTD) [1, 76][11]:

The NTD is first known for being a keystone of TDP-43 polymerization. Indeed, dimers are formed by head-to-head interactions between NTDs, and the polymer thus obtained allows for pre-mRNA splicing.[12] However, further oligomerization brings to more toxic accumulates. This process of polymerization into dimers, larger forms or just stabilizing monomers is dependent on TDP-43 conformational equilibrium between monomers, homodimers and oligomers. Hence, in diseased cells, TDP-43 is overexpressed and this leads to a NTD showing high propensity to aggregate. Contrary to this, in normal cells, normal levels of TDP-43 allow for folded NTD, preventing aggregates and polymers formation.

More recently, this domain was found to have a ubiquitin-like structure. It bears 27,6% of homology with Ubiquitin-1 and a β1-β2-α1-β3-β4-β5-β6 + 2*SO42- form[13]. Ubiquitin-like domain are usually associated with a greater affinity for RNA/DNA. However, in the unique case of TDP-43, the Ubiquitin-like NTD binds directly to ssDNA. This interaction permits the conformational equilibrium cited higher to shift towards non-aggregated forms[6].

The domain spanning from [1,80] has a solenoid-like structure which sterically gaps aggregation prone C-term region[12].

All of this raises the possibility that NTD and the RNA Recognition Motifs (later on defined) could cooperatively interact with nucleic acids to accomplish TDP-43’s physiological functions[7].

Mitochondrial Localization Signal:[14]

There are six M to be accounted on TDP-43’s amino acid sequence, although only M1, M3, and M5 were shown to be essential for M localization. Indeed, their ablation leads to a lessened mitochondrial localization.

These localizing sequences are found on the following amino acids:

M1: [35, 41], M2: [105, 112], M3: [146-150], M4: [228, 235], M5: [294, 300], M6: [228, 236].

Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS), [82, 98]:

This domain is of critical importance in ALS, and such is witnessed by the depletion or the mutations (notably A90V) of this domain, which cause loss-of-function from nucleus and promote aggregating, two processes very likely to conduct to TDP-43’s toxic gain of function[2].

It is thereby of the utmost importance to note that TDP-43’s nuclear localization is absolutely critical for it to fulfill its physiological functions[15].

RNA Recognition Motif 1 (RRM1), [105, 181]:

Much like many hnRNPs, TDP-43’s RRMs encompass highly conserved motifs of primary importance for fulfilling their function. Both RRMs follow this pattern: β1-α1-β2-β3-α2-β4-β5[12], which allows them to bind to both RNA and DNA onto UG/TG-repeats of 3’UTR (Untranslated Terminal Regions) end of mRNA/DNA[16].

These sequences mainly ensure mRNA processing, RNA export and RNA stabilizing. It is notaby thanks to these sequences that TDP-43 importantly binds to its own mRNA regulats its very own solubility and polymerization.

RRM2 [191, 261]:

In pathological conditions, it notably binds to p65/NF-kB, an apoptosis implicated factor, and is thus a potential therapeutic target. Moreover it can be burdened with a mutation, D169G, altering a key cleaving site for regulating formation of toxic inclusions[17].

Nuclear Export Signal (NES), [239, 251]:

This sequence probably bears a role in TDP-43’s shuttling function, and was recently found using a prediction algorithm[10].

Disordered Glycin Rich C-terminal domain (CTD), [277, 414]:

Much like 70 other RNA binding proteins, TDP-43 bears a Q/N rich domain [344, 366] which resembles yeast prion sequence. This sequence is called a Prion-Like Domain (PLD).[18]

PLDs are low complexity sequences that have been reported to mediate gene regulation via Liquid-Liquid Phase Transition (LLP) thus driving RNP granule assembly[12] . Forming these microscopically visible RNP granules is thought to induce more effective gene regulatory process[19].

It is here noted that LLP are reversible phenomenons of de-mixing a solution into two distinct liquid phases, hereby forming granules.

This CTD is often reported to play important role in pathogenic behavior of TDP-43:

RNPs granules could also have a role in stress response, and thus, aging, or persistance stress could lead the LLPs to turn into irreversible Liquid Solid Phase sepration, pathological aggregates notably found in ALS neurons[20].

CTD’s disorganized structure can turn into a full fledged Amyloid-like Beta-sheet rich structure causing it to adopt prion-like properties which will be detailed later on[12] .

Moreover, CTFs are a common maker in diseased neurons and are argued to be of high toxicity.

However, notice is to be taken that some points are not always consensual. Indeed, due to its hydrophobic structure, TDP-43 can be hard to analyze, and parts of it remain somewhat vague. Precise sites of phosphorylation, methylation, or even binding are still a bit elusive[12].

Function

TDP-43 is a transcriptional repressor that binds to chromosomally integrated TAR DNA and represses HIV-1 transcription. In addition, this protein regulates alternate splicing of the CFTR gene. In particular, TDP-43 is a splicing factor binding to the intron8/exon9 junction of the CFTR gene and to the intron2/exon3 region of the apoA-II gene.[21][22] A similar pseudogene is present on chromosome 20.[23]

TDP-43 has been shown to bind both DNA and RNA and have multiple functions in transcriptional repression, pre-mRNA splicing and translational regulation. Recent work has characterized the transcriptome-wide binding sites revealing that thousands of RNAs are bound by TDP-43 in neurons.[24]

TDP-43 was originally identified as a transcriptional repressor that binds to chromosomally integrated trans-activation response element (TAR) DNA and represses HIV-1 transcription.[5] It was also reported to regulate alternate splicing of the CFTR gene and the apoA-II gene.[25][26]

In spinal motor neurons TDP-43 has also been shown in humans to be a low molecular weight neurofilament (hNFL) mRNA-binding protein.[27] It has also shown to be a neuronal activity response factor in the dendrites of hippocampal neurons suggesting possible roles in regulating mRNA stability, transport and local translation in neurons.[28]

It has been demonstrated that zinc ions are able to induce aggregation of endogenous TDP-43 in cells.[29] Moreover, zinc could bind to RNA binding domain of TDP-43 and induce the formation of amyloid-like aggregates in vitro.[30]

DNA repair

TDP-43 protein is a key element of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) enzymatic pathway that repairs DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in pluripotent stem cell-derived motor neurons.[31] TDP-43 is rapidly recruited to DSBs where it acts as a scaffold for the further recruitment of the XRCC4-DNA ligase protein complex that then acts to seal the DNA breaks. In TDP-43 depleted human neural stem cell-derived motor neurons, as well as in sporadic ALS patients’ spinal cord specimens there is significant DSB accumulation and reduced levels of NHEJ.[31]

Clinical significance

A hyper-phosphorylated, ubiquitinated and cleaved form of TDP-43—known as pathologic TDP43—is the major disease protein in ubiquitin-positive, tau-, and alpha-synuclein-negative frontotemporal dementia (FTLD-TDP, previously referred to as FTLD-U[32]) and in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).[33][34] Elevated levels of the TDP-43 protein have also been identified in individuals diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and has also been associated with ALS leading to the inference that athletes who have experienced multiple concussions and other types of head injury are at an increased risk for both encephalopathy and motor neuron disease (ALS).[35] Abnormalities of TDP-43 also occur in an important subset of Alzheimer's disease patients, correlating with clinical and neuropathologic features indexes.[36] Misfolded TDP-43 is found in the brains of older adults over age 85 with limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, (LATE), a form of dementia. New monoclonal antibodies, 2G11 and 2H1, have been developed to specify different TDP-43 inclusion types that occur across neurodegenerative diseases, without relying on hyper-phosphorylated epitopes.[37] These antibodies were raised against an epitope within the RRM2 domain (amino acid residues 198–216).[37]

HIV-1, the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), contains an RNA genome that produces a chromosomally integrated DNA during the replicative cycle. Activation of HIV-1 gene expression by the transactivator "Tat" is dependent on an RNA regulatory element (TAR) located "downstream" (i.e. to-be transcribed at a later point in time) of the transcription initiation site.

Mutations in the TARDBP gene are associated with neurodegenerative disorders including frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).[38] In particular, the TDP-43 mutants M337V and Q331K are being studied for their roles in ALS.[39][40][41] Cytoplasmic TDP-43 pathology is the dominant histopathological feature of multisystem proteinopathy.[42] The N-terminal domain, which contributes importantly to the aggregation of the C-terminal region, has a novel structure with two negatively charged loops.[43] A recent study has demonstrated that cellular stress can trigger the abnormal cytoplasmic mislocalisation of TDP-43 in spinal motor neurons in vivo, providing insight into how TDP-43 pathology may develop in sporadic ALS patients.[44]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000120948 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000041459 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Ou SH, Wu F, Harrich D, García-Martínez LF, Gaynor RB (June 1995). "Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs". Journal of Virology. 69 (6): 3584–96. doi:10.1128/JVI.69.6.3584-3596.1995. PMC 189073. PMID 7745706.

- ^ a b c Afroz T, Hock EM, Ernst P, Foglieni C, Jambeau M, Gilhespy L, Laferriere F, Maniecka Z, Plückthun A, Mittl P, Paganetti P, Allain FH, Polymenidou M (June 2017). "Functional and dynamic polymerization of the ALS-linked protein TDP-43 antagonizes its pathologic aggregation". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 45. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8...45A. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00062-0. PMC 5491494. PMID 28663553.

- ^ a b Wang A, Conicella AE, Schmidt HB, Martin EW, Rhoads SN, Reeb AN, Nourse A, Ramirez Montero D, Ryan VH, Rohatgi R, Shewmaker F, Naik MT, Mittag T, Ayala YM, Fawzi NL (March 1, 2018). "A single N-terminal phosphomimic disrupts TDP-43 polymerization, phase separation, and RNA splicing". EMBO Journal. 37 (5): e97452. doi:10.15252/embj.201797452. PMC 5830921. PMID 29438978.

- ^ Lukavsky PJ, Daujotyte D, Tollervey JR, Ule J, Stuani C, Buratti E, Baralle FE, Damberger FF, Allain FH (December 2013). "Molecular basis of UG-rich RNA recognition by the human splicing factor TDP-43". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 20 (12): 1443–1449. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2698. PMID 2424061. S2CID 13783277.

- ^ Conicella AE, Zerze GH, Mittal J, Fawzi NL (6 September 2016). "ALS Mutations Disrupt Phase Separation Mediated by α-Helical Structure in the TDP-43 Low-Complexity C-Terminal Domain". Structure. 24 (9): 1537–49. doi:10.1016/j.str.2016.07.007. PMC 5014597. PMID 27545621.

- ^ a b c Vivoli Vega M, Nigro A, Luti S, Capitini C, Fani G, Gonnelli L, Boscaro F, Chiti F (October 2019). "Isolation and characterization of soluble human full-length TDP-43 associated with neurodegeneration". FASEB J. 33 (10): 10780–93. doi:10.1096/fj.201900474R. PMID 31287959.

- ^ Qin, Haina; Lim, Liang-Zhong; Wei, Yuanyuan; Song, Jianxing (2014-12-30). "TDP-43 N terminus encodes a novel ubiquitin-like fold and its unfolded form in equilibrium that can be shifted by binding to ssDNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (52): 18619–18624. doi:10.1073/pnas.1413994112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4284588. PMID 25503365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ a b c d e f Prasad, Archana; Bharathi, Vidhya; Sivalingam, Vishwanath; Girdhar, Amandeep; Patel, Basant K. (2019-02-14). "Molecular Mechanisms of TDP-43 Misfolding and Pathology in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis". Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 12: 25. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2019.00025. ISSN 1662-5099. PMC 6382748. PMID 30837838.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "TARDBP TAR DNA binding protein [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ^ Huang, Chunhui; Yan, Sen; Zhang, Zaijun (2020-12). "Maintaining the balance of TDP-43, mitochondria, and autophagy: a promising therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases". Translational Neurodegeneration. 9 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/s40035-020-00219-w. ISSN 2047-9158. PMC 7597011. PMID 33126923.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ratti, Antonia; Buratti, Emanuele (2016-08). "Physiological functions and pathobiology of TDP-43 and FUS/TLS proteins". Journal of Neurochemistry. 138: 95–111. doi:10.1111/jnc.13625.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Qin, Haina; Lim, Liang-Zhong; Wei, Yuanyuan; Song, Jianxing (2014-12-30). "TDP-43 N terminus encodes a novel ubiquitin-like fold and its unfolded form in equilibrium that can be shifted by binding to ssDNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (52): 18619–18624. doi:10.1073/pnas.1413994112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4284588. PMID 25503365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Pozzi, Silvia; Thammisetty, Sai Sampath; Codron, Philippe; Rahimian, Reza; Plourde, Karine Valérie; Soucy, Geneviève; Bareil, Christine; Phaneuf, Daniel; Kriz, Jasna; Gravel, Claude; Julien, Jean-Pierre (2019-02-25). "Virus-mediated delivery of antibody targeting TAR DNA-binding protein-43 mitigates associated neuropathology". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 129 (4): 1581–1595. doi:10.1172/JCI123931. ISSN 0021-9738.

- ^ Nonaka, Takashi; Masuda-Suzukake, Masami; Arai, Tetsuaki; Hasegawa, Yoko; Akatsu, Hiroyasu; Obi, Tomokazu; Yoshida, Mari; Murayama, Shigeo; Mann, David M.A.; Akiyama, Haruhiko; Hasegawa, Masato (2013-07). "Prion-like Properties of Pathological TDP-43 Aggregates from Diseased Brains". Cell Reports. 4 (1): 124–134. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); no-break space character in|first9=at position 6 (help) - ^ Fan, Alexander C.; Leung, Anthony K. L. (2016), Yeo, Gene W. (ed.), "RNA Granules and Diseases: A Case Study of Stress Granules in ALS and FTLD", RNA Processing, vol. 907, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 263–296, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29073-7_11, ISBN 978-3-319-29071-3, PMC 5247449, PMID 27256390, retrieved 2021-12-13

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Hennig, Sven; Kong, Geraldine; Mannen, Taro; Sadowska, Agata; Kobelke, Simon; Blythe, Amanda; Knott, Gavin J.; Iyer, K. Swaminathan; Ho, Diwei; Newcombe, Estella A.; Hosoki, Kana (2015-08-17). "Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles". Journal of Cell Biology. 210 (4): 529–539. doi:10.1083/jcb.201504117. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 4539981. PMID 26283796.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Buratti E, Dörk T, Zuccato E, Pagani F, Romano M, Baralle FE (April 2001). "Nuclear factor TDP-43 and SR proteins promote in vitro and in vivo CFTR exon 9 skipping". The EMBO Journal. 20 (7): 1774–84. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.7.1774. PMC 145463. PMID 11285240.

- ^ Kuo PH, Doudeva LG, Wang YT, Shen CK, Yuan HS (April 2009). "Structural insights into TDP-43 in nucleic-acid binding and domain interactions". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (6): 1799–808. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp013. PMC 2665213. PMID 19174564.

- ^ Gene Result

- ^ Sephton CF, Cenik C, Kucukural A, Dammer EB, Cenik B, Han Y, Dewey CM, Roth FP, Herz J, Peng J, Moore MJ, Yu G (January 2011). "Identification of neuronal RNA targets of TDP-43-containing ribonucleoprotein complexes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (2): 1204–15. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.190884. PMC 3020728. PMID 21051541.

- ^ Buratti E, Baralle FE (September 2001). "Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (39): 36337–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M104236200. PMID 11470789.

- ^ Mercado PA, Ayala YM, Romano M, Buratti E, Baralle FE (2005-10-12). "Depletion of TDP 43 overrides the need for exonic and intronic splicing enhancers in the human apoA-II gene". Nucleic Acids Research. 33 (18): 6000–10. doi:10.1093/nar/gki897. PMC 1270946. PMID 16254078.

- ^ Strong MJ, Volkening K, Hammond R, Yang W, Strong W, Leystra-Lantz C, Shoesmith C (June 2007). "TDP43 is a human low molecular weight neurofilament (hNFL) mRNA-binding protein". Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 35 (2): 320–7. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.007. PMID 17481916. S2CID 42553015.

- ^ Wang IF, Wu LS, Chang HY, Shen CK (May 2008). "TDP-43, the signature protein of FTLD-U, is a neuronal activity-responsive factor". Journal of Neurochemistry. 105 (3): 797–806. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05190.x. PMID 18088371. S2CID 41139555.

- ^ Caragounis A, Price KA, Soon CP, Filiz G, Masters CL, Li QX, Crouch PJ, White AR (May 2010). "Zinc induces depletion and aggregation of endogenous TDP-43". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 48 (9): 1152–61. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.035. PMID 20138212.

- ^ Garnier C, Devred F, Byrne D, Puppo R, Roman AY, Malesinski S, Golovin AV, Lebrun R, Ninkina NN, Tsvetkov PO (July 2017). "Zinc binding to RNA recognition motif of TDP-43 induces the formation of amyloid-like aggregates". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 6812. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.6812G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07215-7. PMC 5533730. PMID 28754988.

- ^ a b Mitra J, Guerrero EN, Hegde PM, Liachko NF, Wang H, Vasquez V, Gao J, Pandey A, Taylor JP, Kraemer BC, Wu P, Boldogh I, Garruto RM, Mitra S, Rao KS, Hegde ML (2019). "Motor neuron disease-associated loss of nuclear TDP-43 is linked to DNA double-strand break repair defects". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116 (10): 4696–4705. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818415116. PMC 6410842. PMID 30770445.

- ^ Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Baborie A, Sampathu DM, Du Plessis D, Jaros E, Perry RH, Trojanowski JQ, Mann DM, Lee VM (July 2011). "A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology". Acta Neuropathologica. 122 (1): 111–3. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0845-8. PMC 3285143. PMID 21644037.

- ^ Bräuer S, Zimyanin V, Hermann A (April 2018). "Prion-like properties of disease-relevant proteins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Journal of Neural Transmission. 125 (4): 591–613. doi:10.1007/s00702-018-1851-y. PMID 29417336. S2CID 3895544.

- ^ Lau DH, Hartopp N, Welsh NJ, Mueller S, Glennon EB, Mórotz GM, Annibali A, Gomez-Suaga P, Stoica R, Paillusson S, Miller CC (February 2018). "Disruption of ER-mitochondria signalling in fronto-temporal dementia and related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Cell Death & Disease. 9 (3): 327. doi:10.1038/s41419-017-0022-7. PMC 5832427. PMID 29491392.

- ^ Schwarz, Alan. "Study Says Brain Trauma Can Mimic A.L.S.", The New York Times, August 18, 2010. Accessed August 18, 2010.

- ^ Tremblay C, St-Amour I, Schneider J, Bennett DA, Calon F (September 2011). "Accumulation of transactive response DNA binding protein 43 in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 70 (9): 788–98. doi:10.1097/nen.0b013e31822c62cf. PMC 3197017. PMID 21865887.

- ^ a b Trejo-Lopez JA, Sorrentino ZA, Riffe CJ, Lloyd GM, Labuzan SA, Dickson DW, et al. (November 2020). "Novel monoclonal antibodies targeting the RRM2 domain of human TDP-43 protein". Neuroscience Letters. 738: 135353. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135353. PMC 7924408. PMID 32905837.

- ^ Kwong LK, Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (July 2007). "TDP-43 proteinopathy: the neuropathology underlying major forms of sporadic and familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease". Acta Neuropathologica. 114 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0226-5. PMID 17492294. S2CID 20773388.

- ^ Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, Baralle F, de Belleroche J, Mitchell JD, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A, Miller CC, Nicholson G, Shaw CE (March 2008). "TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Science. 319 (5870): 1668–72. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1668S. doi:10.1126/science.1154584. PMC 7116650. PMID 18309045. S2CID 28744172.

- ^ Gendron TF, Rademakers R, Petrucelli L (2013). "TARDBP mutation analysis in TDP-43 proteinopathies and deciphering the toxicity of mutant TDP-43". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 33 Suppl 1 (suppl 1): S35–45. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-129036. PMC 3532959. PMID 22751173.

- ^ Babić Leko M, Župunski V, Kirincich J, Smilović D, Hortobágyi T, Hof PR, Šimić G (2019). "Molecular Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration Related to C9orf72 Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion". Behavioural Neurology. 2019: 2909168. doi:10.1155/2019/2909168. PMC 6350563. PMID 30774737.

- ^ Kim HJ, Kim NC, Wang YD, Scarborough EA, Moore J, Diaz Z, MacLea KS, Freibaum B, Li S, Molliex A, Kanagaraj AP, Carter R, Boylan KB, Wojtas AM, Rademakers R, Pinkus JL, Greenberg SA, Trojanowski JQ, Traynor BJ, Smith BN, Topp S, Gkazi AS, Miller J, Shaw CE, Kottlors M, Kirschner J, Pestronk A, Li YR, Ford AF, Gitler AD, Benatar M, King OD, Kimonis VE, Ross ED, Weihl CC, Shorter J, Taylor JP (March 2013). "Mutations in prion-like domains in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 cause multisystem proteinopathy and ALS". Nature. 495 (7442): 467–73. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..467K. doi:10.1038/nature11922. PMC 3756911. PMID 23455423.

- ^ .Mompeán M, Romano V, Pantoja-Uceda D, Stuani C, Baralle FE, Buratti E, Laurents DV (April 2016). "The TDP-43 N-terminal domain structure at high resolution". The FEBS Journal. 283 (7): 1242–60. doi:10.1111/febs.13651. hdl:10261/162654. PMID 26756435.

- ^ Svahn AJ, Don EK, Badrock AP, Cole NJ, Graeber MB, Yerbury JJ, Chung R, Morsch M (September 2018). "Nucleo-cytoplasmic transport of TDP-43 studied in real time: impaired microglia function leads to axonal spreading of TDP-43 in degenerating motor neurons". Acta Neuropathologica. 136 (3): 445–459. doi:10.1007/s00401-018-1875-2. PMC 6096729. PMID 29943193.

Further reading

- Kwong LK, Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (July 2007). "TDP-43 proteinopathy: the neuropathology underlying major forms of sporadic and familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease". Acta Neuropathologica. 114 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1007/s00401-007-0226-5. PMID 17492294. S2CID 20773388.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (January 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Tokai N, Fujimoto-Nishiyama A, Toyoshima Y, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Inoue J, Yamamota T (February 1996). "Kid, a novel kinesin-like DNA binding protein, is localized to chromosomes and the mitotic spindle". The EMBO Journal. 15 (3): 457–67. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00378.x. PMC 449964. PMID 8599929.

- Bonaldo MF, Lennon G, Soares MB (September 1996). "Normalization and subtraction: two approaches to facilitate gene discovery". Genome Research. 6 (9): 791–806. doi:10.1101/gr.6.9.791. PMID 8889548.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (October 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA (November 2000). "DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination". Genome Research. 10 (11): 1788–95. doi:10.1101/gr.143000. PMC 310948. PMID 11076863.

- Wiemann S, Weil B, Wellenreuther R, Gassenhuber J, Glassl S, Ansorge W, Böcher M, Blöcker H, Bauersachs S, Blum H, Lauber J, Düsterhöft A, Beyer A, Köhrer K, Strack N, Mewes HW, Ottenwälder B, Obermaier B, Tampe J, Heubner D, Wambutt R, Korn B, Klein M, Poustka A (March 2001). "Toward a catalog of human genes and proteins: sequencing and analysis of 500 novel complete protein coding human cDNAs". Genome Research. 11 (3): 422–35. doi:10.1101/gr.GR1547R. PMC 311072. PMID 11230166.

- Buratti E, Dörk T, Zuccato E, Pagani F, Romano M, Baralle FE (April 2001). "Nuclear factor TDP-43 and SR proteins promote in vitro and in vivo CFTR exon 9 skipping". The EMBO Journal. 20 (7): 1774–84. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.7.1774. PMC 145463. PMID 11285240.

- Buratti E, Baralle FE (September 2001). "Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (39): 36337–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M104236200. PMID 11470789.

- Wang IF, Reddy NM, Shen CK (October 2002). "Higher order arrangement of the eukaryotic nuclear bodies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (21): 13583–8. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9913583W. doi:10.1073/pnas.212483099. PMC 129717. PMID 12361981.

- Lehner B, Sanderson CM (July 2004). "A protein interaction framework for human mRNA degradation". Genome Research. 14 (7): 1315–23. doi:10.1101/gr.2122004. PMC 442147. PMID 15231747.

- Wiemann S, Arlt D, Huber W, Wellenreuther R, Schleeger S, Mehrle A, Bechtel S, Sauermann M, Korf U, Pepperkok R, Sültmann H, Poustka A (October 2004). "From ORFeome to biology: a functional genomics pipeline". Genome Research. 14 (10B): 2136–44. doi:10.1101/gr.2576704. PMC 528930. PMID 15489336.

- Buratti E, Brindisi A, Giombi M, Tisminetzky S, Ayala YM, Baralle FE (November 2005). "TDP-43 binds heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B through its C-terminal tail: an important region for the inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exon 9 splicing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (45): 37572–84. doi:10.1074/jbc.M505557200. PMID 16157593.

- Stelzl U, Worm U, Lalowski M, Haenig C, Brembeck FH, Goehler H, Stroedicke M, Zenkner M, Schoenherr A, Koeppen S, Timm J, Mintzlaff S, Abraham C, Bock N, Kietzmann S, Goedde A, Toksöz E, Droege A, Krobitsch S, Korn B, Birchmeier W, Lehrach H, Wanker EE (September 2005). "A human protein-protein interaction network: a resource for annotating the proteome". Cell. 122 (6): 957–68. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.029. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0010-8592-0. PMID 16169070. S2CID 8235923.

- Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Dricot A, Li N, Berriz GF, Gibbons FD, Dreze M, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Klitgord N, Simon C, Boxem M, Milstein S, Rosenberg J, Goldberg DS, Zhang LV, Wong SL, Franklin G, Li S, Albala JS, Lim J, Fraughton C, Llamosas E, Cevik S, Bex C, Lamesch P, Sikorski RS, Vandenhaute J, Zoghbi HY, Smolyar A, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Roth FP, Vidal M (October 2005). "Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network". Nature. 437 (7062): 1173–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1173R. doi:10.1038/nature04209. PMID 16189514. S2CID 4427026.

- Mehrle A, Rosenfelder H, Schupp I, del Val C, Arlt D, Hahne F, Bechtel S, Simpson J, Hofmann O, Hide W, Glatting KH, Huber W, Pepperkok R, Poustka A, Wiemann S (January 2006). "The LIFEdb database in 2006". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (Database issue): D415–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkj139. PMC 1347501. PMID 16381901.

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on TARDBP-Related Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q13148 (TAR DNA-binding protein 43) at the PDBe-KB.