Mitotic catastrophe: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

copied from sandbox User:Your Nsterge2/sandbox |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:RPE_cell_that_has_been_treated_with_taxol_and_undergone_mitotic_catastrophe.png|thumb|239x239px|A cell that has been treated with with taxol and had a catastrophic mitosis. The cell has become multinucleated after an unsuccessful mitosis.]] |

|||

'''Mitotic catastrophe''' refers to a mechanism of delayed mitosis-linked [[cell death]], a sequence of events resulting from premature or inappropriate entry of cells into [[mitosis]] that can be caused by chemical or physical stresses.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ianzini F, Mackey MA | title = Spontaneous premature chromosome condensation and mitotic catastrophe following irradiation of HeLa S3 cells | journal = International Journal of Radiation Biology | volume = 72 | issue = 4 | pages = 409–21 | date = October 1997 | pmid = 9343106 | doi = 10.1080/095530097143185 }}</ref> Mitotic catastrophe is unrelated to [[Apoptosis|programmed cell death]] and is observed in cells lacking functional apoptotic pathways.<ref name="bookchap">{{cite book|last1=Ianzini|first1=Fiorenza|last2=Mackey|first2=Michael A | name-list-style = vanc |chapter=Mitotic Catastrophe|title=Apoptosis, Senescence, and Cancer|date=2007|publisher=Humana Press|isbn=978-1-58829-527-9|pages=73–91 }}</ref> It has been observed following delayed DNA damage induced by [[ionizing radiation]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ianzini F, Mackey MA | title = Delayed DNA damage associated with mitotic catastrophe following X-irradiation of HeLa S3 cells | journal = Mutagenesis | volume = 13 | issue = 4 | pages = 337–44 | date = July 1998 | pmid = 9717169 | doi = 10.1093/mutage/13.4.337 | doi-access = free }}</ref> It can also be triggered by agents influencing the stability of microtubule spindles, various anticancer drugs and mitotic failure caused by defective cell cycle checkpoints.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Castedo M, Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Andreau K, Medema R, Kroemer G | title = Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition | journal = Oncogene | volume = 23 | issue = 16 | pages = 2825–37 | date = April 2004 | pmid = 15077146 | doi = 10.1038/sj.onc.1207528 | doi-access = free }}</ref> This mechanism can activate after detection of imperfections in the segregation of genetic material between daughter cells.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Korsnes|first1=Mónica Suárez|last2=Korsnes|first2=Reinert|date=2017-03-31|title=Mitotic Catastrophe in BC3H1 Cells following Yessotoxin Exposure|journal=Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology|volume=5|page=30|doi=10.3389/fcell.2017.00030|pmid=28409150|pmc=5374163|issn=2296-634X|doi-access=free}}</ref> Mitotic catastrophe is the primary mechanism underlying reproductive cell death in cancer cells treated with [[ionizing radiation]].<ref name="bookchap" /> |

|||

'''Mitotic Catastrophe''' has been defined as either an cellular mechanism to prevent cancerous cell proliferation that results in the cell no longer dividing or [[cell death]] in cells that undergo a defective [[mitosis]] or as a mode of cellular death that occurs following improper [[cell cycle]] progression or entrance<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Galluzzi |first=Lorenzo |last2=Vitale |first2=Ilio |last3=Aaronson |first3=Stuart A. |last4=Abrams |first4=John M. |last5=Adam |first5=Dieter |last6=Agostinis |first6=Patrizia |last7=Alnemri |first7=Emad S. |last8=Altucci |first8=Lucia |last9=Amelio |first9=Ivano |last10=Andrews |first10=David W. |last11=Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli |first11=Margherita |last12=Antonov |first12=Alexey V. |last13=Arama |first13=Eli |last14=Baehrecke |first14=Eric H. |last15=Barlev |first15=Nickolai A. |date=March 2018 |title=Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018 |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41418-017-0012-4 |journal=Cell Death & Differentiation |language=en |volume=25 |issue=3 |pages=486–541 |doi=10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4 |issn=1476-5403}}</ref><ref name=":3">{{Cite journal |last=Castedo |first=Maria |last2=Perfettini |first2=Jean-Luc |last3=Roumier |first3=Thomas |last4=Andreau |first4=Karine |last5=Medema |first5=Rene |last6=Kroemer |first6=Guido |date=April 2004 |title=Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/1207528 |journal=Oncogene |language=en |volume=23 |issue=16 |pages=2825–2837 |doi=10.1038/sj.onc.1207528 |issn=1476-5594}}</ref>. Mitotic catastrophe can be induced by prolonged activation of the [[Spindle checkpoint|spindle assembly checkpoint]], errors in mitosis, or DNA damage and functioned to prevent genomic instability<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Vitale |first=Ilio |last2=Galluzzi |first2=Lorenzo |last3=Castedo |first3=Maria |last4=Kroemer |first4=Guido |date=June 2011 |title=Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm3115 |journal=Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology |language=en |volume=12 |issue=6 |pages=385–392 |doi=10.1038/nrm3115 |issn=1471-0080}}</ref>. It is a mechanism that is being researched as a potential therapeutic target in [[Cancer|cancers]], and numerous approved therapeutics induce mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Denisenko |first=Tatiana V. |last2=Sorokina |first2=Irina V. |last3=Gogvadze |first3=Vladimir |last4=Zhivotovsky |first4=Boris |date=January 2016 |title=Mitotic catastrophe and cancer drug resistance: A link that must to be broken |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26830311/ |journal=Drug Resistance Updates: Reviews and Commentaries in Antimicrobial and Anticancer Chemotherapy |volume=24 |pages=1–12 |doi=10.1016/j.drup.2015.11.002 |issn=1532-2084 |pmid=26830311}}</ref>. |

|||

Not all cells die immediately following abnormal mitosis caused by mitotic catastrophe, but many do. Cells that do not immediately die are likely to create [[aneuploidy|aneuploid cells]] following subsequent attempts at cell division posing a risk of [[oncogenesis]] (i.e. potentially leading to cancer). A very small fraction of these aneuploid cells produced by mitotic catastrophe might later reduce DNA ploidy by reductive division involving meiotic cell division pathways.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Prieur-Carrillo G, Chu K, Lindqvist J, Dewey WC | title = Computerized video time-lapse (CVTL) analysis of the fate of giant cells produced by X-irradiating EJ30 human bladder carcinoma cells | journal = Radiation Research | volume = 159 | issue = 6 | pages = 705–12 | date = June 2003 | pmid = 12751952 | doi = 10.1667/rr3009 | bibcode = 2003RadR..159..705P | s2cid = 1144630 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Erenpreisa J, Kalejs M, Ianzini F, Kosmacek EA, Mackey MA, Emzinsh D, Cragg MS, Ivanov A, Illidge TM | title = Segregation of genomes in polyploid tumour cells following mitotic catastrophe | journal = Cell Biology International | volume = 29 | issue = 12 | pages = 1005–11 | date = December 2005 | pmid = 16314119 | doi = 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.10.008 | s2cid = 25383615 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ianzini F, Kosmacek EA, Nelson ES, Napoli E, Erenpreisa J, Kalejs M, Mackey MA | title = Activation of meiosis-specific genes is associated with depolyploidization of human tumor cells following radiation-induced mitotic catastrophe | journal = Cancer Research | volume = 69 | issue = 6 | pages = 2296–304 | date = March 2009 | pmid = 19258501 | pmc = 2657811 | doi = 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-3364 }}</ref> |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== Term usage == |

|||

Multiple attempts to specifically define mitotic catastrophe have been made since the term was first used to describe a temperature dependent lethality in the yeast, ''[[Schizosaccharomyces pombe]],'' that demonstrated abnormal segregation of chromosomes<ref name=":32">{{Cite journal |last=Castedo |first=Maria |last2=Perfettini |first2=Jean-Luc |last3=Roumier |first3=Thomas |last4=Andreau |first4=Karine |last5=Medema |first5=Rene |last6=Kroemer |first6=Guido |date=April 2004 |title=Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/1207528 |journal=Oncogene |language=en |volume=23 |issue=16 |pages=2825–2837 |doi=10.1038/sj.onc.1207528 |issn=1476-5594}}</ref><ref name=":22">{{Cite journal |last=Vitale |first=Ilio |last2=Galluzzi |first2=Lorenzo |last3=Castedo |first3=Maria |last4=Kroemer |first4=Guido |date=June 2011 |title=Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm3115 |journal=Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology |language=en |volume=12 |issue=6 |pages=385–392 |doi=10.1038/nrm3115 |issn=1471-0080}}</ref>. The term has been used to define a mechanism of cellular death that occurs while a cell is in mitosis or as a method of oncosuppression that prevents potentially tumorigenic cells from dividing.<ref name=":22" /> This oncosuppression is accomplished by initiating a form of cell death such as [[apoptosis]] or [[necrosis]] or by inducing [[cellular senescence]]<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

=== Mechanism to prevent cancer development === |

|||

[[File:Mitotic_Catastrophe_Diagram_version_2.png|thumb|557x557px|Diagram showing events that can lead to mitotic catastrophe and the potential outcomes.]] |

|||

One usage of the term mitotic catastrophe is to describe an oncosuppressive mechanism (i.e. a mechanism to prevent the proliferation of cancerous cells and the develop of tumors) that occurs when cells undergo and detect a defective [[mitosis]] has occurred<ref name=":02">{{Cite journal |last=Galluzzi |first=Lorenzo |last2=Vitale |first2=Ilio |last3=Aaronson |first3=Stuart A. |last4=Abrams |first4=John M. |last5=Adam |first5=Dieter |last6=Agostinis |first6=Patrizia |last7=Alnemri |first7=Emad S. |last8=Altucci |first8=Lucia |last9=Amelio |first9=Ivano |last10=Andrews |first10=David W. |last11=Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli |first11=Margherita |last12=Antonov |first12=Alexey V. |last13=Arama |first13=Eli |last14=Baehrecke |first14=Eric H. |last15=Barlev |first15=Nickolai A. |date=March 2018 |title=Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018 |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41418-017-0012-4 |journal=Cell Death & Differentiation |language=en |volume=25 |issue=3 |pages=486–541 |doi=10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4 |issn=1476-5403}}</ref>. This definition of this mechanism has been described by the International Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Mc Gee |first=Margaret M. |date=2015 |title=Targeting the Mitotic Catastrophe Signaling Pathway in Cancer |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26491220/ |journal=Mediators of Inflammation |volume=2015 |pages=146282 |doi=10.1155/2015/146282 |issn=1466-1861 |pmc=4600505 |pmid=26491220}}</ref><ref name=":02" />. Under this definition, cells that undergo mitotic catastrophe either senesce and stop dividing or undergo a regulated form of cell death during mitosis or another form of cell death in the next [[G1 phase]] of the cell cycle<ref name=":02" /><ref name=":22" />. The function of this mechanism is to prevent cells from accruing [[Genome instability|genomic instability]] which can lead to tumorigenesis<ref name=":22" /><ref name=":1" />. |

|||

When the cell undergoes cell death during mitosis this is known as mitotic death<ref name=":22" />. This is characterized by high levels of [[cyclin B1]] still present in the cell at the time of cell death indicating the cell never finished mitosis<ref name=":22" />. Mitotic catastrophe can also lead to the cell being fated for cell death by apoptosis or necrosis following [[interphase]] of the cell cycle<ref name=":22" />. However, the timing of cell death can vary from hours after mitosis completes to years later which has been witnessed in human tissues treated with [[Radiation therapy|radiotherapy]]<ref name=":22" />. The least common outcome of mitotic catastrophe is senescence in which the cell stops dividing and enters a permanent cell cycle arrest that prevents the cell from proliferating any further<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

=== Mechanism of cellular death === |

|||

Another usage of the term mitotic catastrophe is to describe a mode of cell death that occurs during mitosis<ref name=":32" />. This cell death can occur due to an accumulation of DNA damage in the presence of improperly functioning DNA structure checkpoints or an improperly functioning spindle assembly checkpoint<ref name=":32" />. Cells that undergo mitotic catastrophe death can lack activation of pathways of the traditional death pathways such as apoptosis<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal |last=Fu |first=Xiao |last2=Li |first2=Mu |last3=Tang |first3=Cuilian |last4=Huang |first4=Zezhi |last5=Najafi |first5=Masoud |date=December 2021 |title=Targeting of cancer cell death mechanisms by resveratrol: a review |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34561763/ |journal=Apoptosis: An International Journal on Programmed Cell Death |volume=26 |issue=11-12 |pages=561–573 |doi=10.1007/s10495-021-01689-7 |issn=1573-675X |pmid=34561763}}</ref>. While more recent definitions of mitotic catastrophe do not use it to describe a bona fide cell death mechanism, some publications describe it as a mechanism of cell death<ref name=":02" /><ref name=":5" />. |

|||

== Causes == |

|||

=== Prolonged spindle assembly checkpoint activation === |

|||

[[File:Spindle_chromosomes-en.png|thumb|304x304px|Mitotic checkpoint (also known as spindle assembly checkpoint) prevents the cell progressing from metaphase to anaphase if not all of the chromosomes are properly attached by mitotic spindles.]] |

|||

Cells have a mechanism to prevent improper segregation of [[Chromosome|chromosomes]] known as the [[Spindle checkpoint|spindle assembly checkpoint]] or mitotic checkpoint<ref name=":22" />. The spindle assembly checkpoint verifies that mitotic spindles have properly attached to the kinetochores of each pair of chromosomes before the chromosomes segregate during cell division<ref name=":1" />. If the [[Spindle apparatus|mitotic spindles]] are not properly attached to the [[Kinetochore|kinetochores]] then the spindle assembly checkpoint will prevent the transition from [[metaphase]] to [[anaphase]]<ref name=":1" />. This mechanism is important to ensure that the DNA within the cell is divided equally between the two daughter cells <ref name=":22" />. When the spindle assembly checkpoint is activated, it arrests the cell in mitosis until all chromosomes are properly attached and aligned<ref name=":22" />. If the checkpoint is activated for a prolonged period it can lead to mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

Prolonged activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint inhibits the [[Anaphase-promoting complex|anaphase promoting complex]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sazonova |first=Elena V. |last2=Petrichuk |first2=Svetlana V. |last3=Kopeina |first3=Gelina S. |last4=Zhivotovsky |first4=Boris |date=2021-12-09 |title=A link between mitotic defects and mitotic catastrophe: detection and cell fate |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34886882/ |journal=Biology Direct |volume=16 |issue=1 |pages=25 |doi=10.1186/s13062-021-00313-7 |issn=1745-6150 |pmc=8656038 |pmid=34886882}}</ref>. Normally, activation of the anaphase promoting complex leads to the separation of sister chromatids and the cell exiting mitosis<ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Lara-Gonzalez |first=Pablo |last2=Pines |first2=Jonathon |last3=Desai |first3=Arshad |date=September 2021 |title=Spindle assembly checkpoint activation and silencing at kinetochores |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34210579/ |journal=Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology |volume=117 |pages=86–98 |doi=10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.06.009 |issn=1096-3634 |pmc=8406419 |pmid=34210579}}</ref>. The mitotic checkpoint complex acts as a negative regulator of the anaphase promoting complex<ref name=":6" />. Unattached kinetochores promote the formation of the mitotic checkpoint complex which is composed of four different proteins known as [[Mad2]], [[CDC20|Cdc20]], [[BUB1|BubR1]], and [[BUB3|Bub3]] in [[Human|humans]]<ref name=":6" />. When the mitotic checkpoint complex is formed, it binds to the anaphase promoting complex and prevents its ability to promote cell cycle progression<ref name=":6" />. |

|||

=== Errors in mitosis === |

|||

[[File:Cyclin_Expression.svg|thumb|479x479px|Expression of cyclin levels during different phases of the cell cycle. Cyclin B promotes progression to mitosis and once the cell is in mitosis normally prevents the cell from exiting mitosis prematurely.]] |

|||

Some cells can have an erroneous mitosis yet survive and undergo another cell division which puts the cell at a higher likelihood to undergo mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":22" />. For instance, cells can undergo a process called mitotic slippage where cells exit mitosis to early before the process of mitosis is finished<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sinha |first=Debottam |last2=Duijf |first2=Pascal H.G. |last3=Khanna |first3=Kum Kum |date=2019-01-02 |title=Mitotic slippage: an old tale with a new twist |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6343733/ |journal=Cell Cycle |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=7–15 |doi=10.1080/15384101.2018.1559557 |issn=1538-4101 |pmc=6343733 |pmid=30601084}}</ref>. In this case, the cell finishes mitosis in the presence of spindle assembly checkpoint signaling which would normally prevent the cell from exiting mitosis<ref name=":22" />. This phenomenon is caused by improper degradation of [[cyclin B1]] and can result in chromosome missegregation events<ref name=":22" />. Cyclin B1 is a major regulator of the cell cycle and guides the cells progression from G2 to M phase<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Ghelli Luserna di Rorà |first=Andrea |last2=Martinelli |first2=Giovanni |last3=Simonetti |first3=Giorgia |date=2019-11-26 |title=The balance between mitotic death and mitotic slippage in acute leukemia: a new therapeutic window? |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6880427/ |journal=Journal of Hematology & Oncology |volume=12 |pages=123 |doi=10.1186/s13045-019-0808-4 |issn=1756-8722 |pmc=6880427 |pmid=31771633}}</ref>. Cyclin B1 works with its binding partner [[Cyclin-dependent kinase 1|CDK1]] to control this progression and the complex is known as the mitotic promoting factor<ref name=":7" />. While the mitotic promoting factor is utilized to guide the cells entry into mitosis, its destruction also guides the cells exit from mitosis<ref name=":7" />. Normally, cyclin B1 degradation is initiated by the anaphase promoting complex after all of the kinetochores have been properly attached by mitotic spindle fibers<ref name=":7" />. However, when cyclin B1 levels are degraded to fast this can result in the cell exiting mitosis prematurely resulting in potential mitotic errors including missegregation of chromosomes<ref name=":7" />. |

|||

[[File:Normal_and_multipolar_mitosis.tif|left|thumb|339x339px|An example of a normal mitosis on the left and a multipolar mitosis on the right. Microtubules are in red and the centrosomes are in yellow.]] |

|||

[[Polyploidy|Tetraploid]] or otherwise [[Aneuploidy|aneuploid]] cells are at higher risk of mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":42">{{Cite journal |last=Denisenko |first=Tatiana V. |last2=Sorokina |first2=Irina V. |last3=Gogvadze |first3=Vladimir |last4=Zhivotovsky |first4=Boris |date=January 2016 |title=Mitotic catastrophe and cancer drug resistance: A link that must to be broken |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26830311/ |journal=Drug Resistance Updates: Reviews and Commentaries in Antimicrobial and Anticancer Chemotherapy |volume=24 |pages=1–12 |doi=10.1016/j.drup.2015.11.002 |issn=1532-2084 |pmid=26830311}}</ref>. Tetraploid cells are cells that have duplicated their genetic material, but have not undergo [[cytokinesis]] to split into two daughter cells and thus remain as one cell<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal |last=Ganem |first=Neil J |last2=Storchova |first2=Zuzana |last3=Pellman |first3=David |date=2007-04-01 |title=Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959437X07000378 |journal=Current Opinion in Genetics & Development |series=Chromosomes and expression mechanisms |language=en |volume=17 |issue=2 |pages=157–162 |doi=10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011 |issn=0959-437X}}</ref>. Aneuploid cells are cells that have an incorrect number of chromosomes including whole additions of chromosomes or complete losses of chromosomes<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ben-David |first=Uri |last2=Amon |first2=Angelika |date=January 2020 |title=Context is everything: aneuploidy in cancer |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31548659/ |journal=Nature Reviews. Genetics |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=44–62 |doi=10.1038/s41576-019-0171-x |issn=1471-0064 |pmid=31548659}}</ref>. Cells with an abnormal number of chromosomes are more likely to have chromosome segregation errors that result in mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":42" />. Cells that become aneuploid often are prevented from further cell growth and division by the activation of tumor suppressor pathways such as p53 which drives the cell to a non-proliferating state known as cellular senescence<ref name=":42" />. Given that aneuploid cells can often become tumorigenic, this mechanism prevents the propagation of these cells and thus prevents the development of cancers in the organism<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

Cells that undergo multipolar divisions, or in other words split into more than 2 daughter cells, are at a higher risk of mitotic catastrophe as well<ref name=":22" />. While many of the progeny of multipolar divisions do not survive do to highly imbalanced chromosome numbers, most of the cells that survive and undergo a subsequent mitosis are likely to experience mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":22" />. These multipolar divisions occur due to the presence of more than two centrosomes<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ogden |first=A |last2=Rida |first2=P C G |last3=Aneja |first3=R |date=August 2012 |title=Let's huddle to prevent a muddle: centrosome declustering as an attractive anticancer strategy |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3392635/ |journal=Cell Death and Differentiation |volume=19 |issue=8 |pages=1255–1267 |doi=10.1038/cdd.2012.61 |issn=1350-9047 |pmc=3392635 |pmid=22653338}}</ref>. [[Centrosome|Centrosomes]] are cellular organelles that acts to organize the mitotic spindle assembly in the cell during mitosis and thus guide the segregation of chromosomes during mitosis<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bornens |first=Michel |date=2021-02-01 |title=Centrosome organization and functions |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X20301986 |journal=Current Opinion in Structural Biology |series=Centrosomal Organization and Assemblies ● Folding and Binding |language=en |volume=66 |pages=199–206 |doi=10.1016/j.sbi.2020.11.002 |issn=0959-440X}}</ref>. Normally, cells will have two centrosomes that guide sister chromatids to opposite poles of the dividing cell<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Doxsey |first=Stephen |last2=Zimmerman |first2=Wendy |last3=Mikule |first3=Keith |date=June 2005 |title=Centrosome control of the cell cycle |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15953548/ |journal=Trends in Cell Biology |volume=15 |issue=6 |pages=303–311 |doi=10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.008 |issn=0962-8924 |pmid=15953548}}</ref>. However, when there are more than two centrosomes present in mitosis they can pull chromosomes in incorrect directions resulting in daughter cells that are inviable<ref name=":9" />. Many cancers have excessive numbers of centrosomes, but to prevent inviable daughter cells, the cancer cells have developed mechanisms to cluster their centrosomes.<ref name=":9" /> When the centrosomes are clustered to two poles of the dividing cell, the chromosomes are segregated properly and two daughter cells are formed.<ref name=":9" />. Thus, cancers that are able to adapt to a higher number of centrosomes are able to are able to prevent mitotic catastrophe and propagate in the presence of their extra centrosomes<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

=== DNA damage === |

|||

High levels of DNA damage that are not repaired before the cell enters mitosis can result in a mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":22" />. Cells that have a compromised [[G2-M DNA damage checkpoint|G2 checkpoint]] do not have the ability to prevent progression through the cell cycle even when there is DNA damage present in the cell's genome<ref name=":22" />. The G2 checkpoint normally functions to stop cells that have damaged DNA from progressing to mitosis<ref>{{Citation |last=Stark |first=George R. |title=Analyzing the G2/M Checkpoint |date=2004 |url=https://doi.org/10.1385/1-59259-788-2:051 |work=Checkpoint Controls and Cancer: Volume 1: Reviews and Model Systems |pages=51–82 |editor-last=Schönthal |editor-first=Axel H. |place=Totowa, NJ |publisher=Humana Press |language=en |doi=10.1385/1-59259-788-2:051 |isbn=978-1-59259-788-8 |access-date=2022-11-26 |last2=Taylor |first2=William R.}}</ref>. The [[G2-M DNA damage checkpoint|G2 checkpoint]] can be compromised if tumor suppressor [[p53]] is no longer present in the cell<ref name=":22" />. The response to DNA damage present during mitosis is different from the response to DNA damage detected during the rest of the cell cycle<ref name=":22" />. Cells can detect DNA defects during the rest of the cell cycle and either repair them if possible or undergo apoptosis of senescence<ref name=":22" />. Given that when this happens the cell does not progress into mitosis it is not considered a mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

== Mitotic catastrophe in cancer == |

|||

=== Prevention of genomic instability === |

|||

[[Genome instability|Genomic instability]] is one of the [[The Hallmarks of Cancer|hallmarks of cancer]] cells and promotes genetic changes (both large chromosomal changes as well as individual nucleotide changes) in cancer cells which can lead to increased levels of tumor progression through genetic variation in the tumor cell.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hanahan |first=Douglas |date=January 2022 |title=Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35022204/ |journal=Cancer Discovery |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=31–46 |doi=10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059 |issn=2159-8290 |pmid=35022204}}</ref> Cancers with a higher level of genomic instability have been shown to have worse patient outcomes than those cancers which have lower levels of genomic instability<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Andor |first=Noemi |last2=Maley |first2=Carlo C. |last3=Ji |first3=Hanlee P. |date=2017-05-01 |title=Genomic instability in cancer: Teetering on the limit of tolerance |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5413432/ |journal=Cancer research |volume=77 |issue=9 |pages=2179–2185 |doi=10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1553 |issn=0008-5472 |pmc=5413432 |pmid=28432052}}</ref>. Cells have gained mechanisms that resist increased genomic instability in cells<ref name=":22" />. Mitotic catastrophe is one way in which cells prevent the propagation of genomically unstable cells<ref name=":22" />. If mitotic catastrophe fails for cells whose genome has become unstable they can propagate uncontrollably and potentially become tumorigenic<ref name=":1" />. |

|||

The level of genomic instability is different across cancer types with epithelial cancers being more genomically unstable than cancers of hematological or mesenchymal origin<ref name=":10">{{Cite journal |last=Pikor |first=Larissa |last2=Thu |first2=Kelsie |last3=Vucic |first3=Emily |last4=Lam |first4=Wan |date=2013 |title=The detection and implication of genome instability in cancer |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3843371/ |journal=Cancer Metastasis Reviews |volume=32 |issue=3 |pages=341–352 |doi=10.1007/s10555-013-9429-5 |issn=0167-7659 |pmc=3843371 |pmid=23633034}}</ref>. [[Mesothelioma]], [[Small-cell carcinoma|small-cell lung cancer]], [[Breast cancer|breast]], [[Ovarian cancer|ovarian]], [[Non-small-cell lung carcinoma|non-small cell lung cancer]], and [[Liver cancer|liver]] cancer exhibit high levels of genomic instability while [[acute lymphoblastic leukemia]], [[Myelodysplastic syndrome|myelodysplasia]], and [[Myeloproliferative neoplasm|myeloproliferative disorder]] have lower levels of instability<ref name=":10" />. |

|||

=== Anticancer therapeutics === |

|||

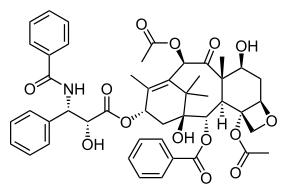

[[File:Taxol.svg|thumb|287x287px|Chemical structure of Paclitaxel (Taxol), an anticancer therapeutic that can induce mitotic catastrophe.]] |

|||

Promotion of mitotic catastrophe in cancer cells is an area of cancer therapeutic research that has garnered interest and is seen as a potential target to overcome resistance developed to current [[Chemotherapy|chemotherapies]]<ref name=":42" />. Cancer cells have been found to be more sensitive to mitotic catastrophe induction than non-cancerous cells in the body<ref name=":22" />. Tumors cells often have inactivated the machinery that is required for apoptosis such as the p53 protein<ref name=":42" />. This is usually achieved by mutations in the p53 protein or by loss of the chromosome region that contains the genetic code for it<ref name=":8">{{Cite journal |last=Kanapathipillai |first=Mathumai |date=2018-05-23 |title=Treating p53 Mutant Aggregation-Associated Cancer |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29789497/ |journal=Cancers |volume=10 |issue=6 |pages=154 |doi=10.3390/cancers10060154 |issn=2072-6694 |pmc=6025594 |pmid=29789497}}</ref>. p53 acts to prevent the propagation of tumor cells and is considered a major tumor suppressor protein<ref name=":8" />. p53 works by either halting progression through the cell cycle when uncontrolled cell division is sensed or it can promote cell death through apoptosis in the presence of irreparable DNA damage<ref name=":8" />. Mitotic catastrophe can occur in a p53 independent fashion and thus presents a therapeutic avenue of interest<ref name=":42" />. Furthermore, doses of DNA damaging drugs lower than lethal levels have been shown to induce mitotic catastrophe<ref name=":42" />. This would allow for administration of a drug while the patient has fewer side effects<ref name=":22" />. |

|||

Cancer therapies can induce mitotic catastrophe by either damaging the cells DNA or inhibiting spindle assembly<ref name=":42" />. Drugs, known as spindle poisons, affect the polymerization or depolymerization of microtubule spindles and thus interfere with the correct formation of the mitotic spindles<ref name=":42" />. When this happens, the spindle assembly checkpoint becomes activated and the transition from metaphase to anaphase is inhibited<ref name=":42" />. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+Cancer drugs that induce mitotic catastrophe |

|||

!Drug |

|||

!Approved uses / clinical trial phase / research use |

|||

!Mechanism of action |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Paclitaxel]]<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|Approved use: AIDS-related [[Kaposi's sarcoma|Kaposi sarcoma]], [[breast cancer]], [[Non-small-cell lung carcinoma|non-small cell lung cancer]], and [[ovarian cancer]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Paclitaxel |url=https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/paclitaxel |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=National Cancer Institute |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| rowspan="2" |Promotes microtuble spindle assembly and prevents the detachment of microtubles preventing the cell from properly entering or exiting mitosis.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zhu |first=Linyan |last2=Chen |first2=Liqun |date=2019-06-13 |title=Progress in research on paclitaxel and tumor immunotherapy |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6567594/ |journal=Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters |volume=24 |pages=40 |doi=10.1186/s11658-019-0164-y |issn=1425-8153 |pmc=6567594 |pmid=31223315}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Docetaxel]]<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|Approved use: Breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, [[prostate cancer]], [[Head and neck cancer|head and neck squamous cell carcinoma]], stomach adenocarcinoma, and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma<ref>{{Cite web |date=2006-10-05 |title=Docetaxel - NCI |url=https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/docetaxel |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=www.cancer.gov |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Vinblastine|Vinblastin]]<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|Approved use: Breast cancer, [[Choriocarcinoma]], [[Hodgkin lymphoma]], Kaposi sarcoma, [[mycosis fungoides]], [[non-Hodgkin lymphoma]], [[Germ cell tumor|testicular germ cell tumors]]<ref>{{Cite web |date=2011-02-03 |title=Vinblastine Sulfate - NCI |url=https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/vinblastinesulfate |access-date=2022-11-29 |website=www.cancer.gov |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| rowspan="2" |Depolymerizes microtubules<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Vincristine|Vinkristine]]<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|Approved use: [[Acute lymphoblastic leukemia]], [[Lymphoma|lymphomas]], [[neuroblastoma]], [[Sarcoma|sarcomas]], and [[Central nervous system tumor|central nervous system tumors]]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Triarico |first=Silvia |last2=Romano |first2=Alberto |last3=Attinà |first3=Giorgio |last4=Capozza |first4=Michele Antonio |last5=Maurizi |first5=Palma |last6=Mastrangelo |first6=Stefano |last7=Ruggiero |first7=Antonio |date=2021-04-16 |title=Vincristine-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (VIPN) in Pediatric Tumors: Mechanisms, Risk Factors, Strategies of Prevention and Treatment |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8073828/ |journal=International Journal of Molecular Sciences |volume=22 |issue=8 |pages=4112 |doi=10.3390/ijms22084112 |issn=1422-0067 |pmc=8073828 |pmid=33923421}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Monastrol]]<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

|Research use |

|||

| rowspan="2" |[[Kinesin-like protein KIF11|EG5]] Inhibitor which perturbs the movement of chromosomes during mitosis.<ref name=":22" /> This perturbation results in cells dying in mitosis or in the subsequent interphase.<ref name=":11">{{Cite journal |last=Garcia-Saez |first=Isabel |last2=Skoufias |first2=Dimitrios A. |date=2021-02-01 |title=Eg5 targeting agents: From new anti-mitotic based inhibitor discovery to cancer therapy and resistance |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006295220306006 |journal=Biochemical Pharmacology |language=en |volume=184 |pages=114364 |doi=10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114364 |issn=0006-2952}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Filanesib|ARRY-520]] (Filanesib)<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

|[[Phases of clinical research|Phase III clinical trial]]: [[multiple myeloma]]<ref name=":11" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Tozasertib|VX-680]]<ref name=":22" /> |

|||

|Pre-clinical research <ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rossari |first=Federico |last2=Minutolo |first2=Filippo |last3=Orciuolo |first3=Enrico |date=2018-06-20 |title=Past, present, and future of Bcr-Abl inhibitors: from chemical development to clinical efficacy |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29925402/ |journal=Journal of Hematology & Oncology |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=84 |doi=10.1186/s13045-018-0624-2 |issn=1756-8722 |pmc=6011351 |pmid=29925402}}</ref> |

|||

| rowspan="2" |[[Aurora kinase A|AURKA]] / [[Aurora kinase B|AURKB]] inhibitor which disrupts the movement of chromosomes and the cytoskeleton during mitosis |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Alisertib|MLN8237]]<ref name=":42" /> |

|||

|Phase I clincial trial: pediatric recurrent [[Atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor|atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors]] and pediatric advanced solid tumors |

|||

Failed clinical trial for adult lymphomas and lung cancer<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Mills |first=Christopher C. |last2=Kolb |first2=EA. |last3=Sampson |first3=Valerie B. |date=2017-12-01 |title=Review: Recent advances of cell cycle inhibitor therapies for pediatric cancer |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5712276/ |journal=Cancer research |volume=77 |issue=23 |pages=6489–6498 |doi=10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2066 |issn=0008-5472 |pmc=5712276 |pmid=29097609}}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Mitosis]] |

|||

* [[Cancer]] |

|||

* [[Apoptosis]] |

|||

* [[Cellular senescence|Senescence]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

<references /> |

|||

[[Category:Cell cycle]] |

[[Category:Cell cycle]] |

||

[[Category:Mitosis]] |

[[Category:Mitosis]] |

||

Revision as of 19:25, 7 December 2022

Mitotic Catastrophe has been defined as either an cellular mechanism to prevent cancerous cell proliferation that results in the cell no longer dividing or cell death in cells that undergo a defective mitosis or as a mode of cellular death that occurs following improper cell cycle progression or entrance[1][2]. Mitotic catastrophe can be induced by prolonged activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint, errors in mitosis, or DNA damage and functioned to prevent genomic instability[3]. It is a mechanism that is being researched as a potential therapeutic target in cancers, and numerous approved therapeutics induce mitotic catastrophe[4].

Term usage

Multiple attempts to specifically define mitotic catastrophe have been made since the term was first used to describe a temperature dependent lethality in the yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, that demonstrated abnormal segregation of chromosomes[5][6]. The term has been used to define a mechanism of cellular death that occurs while a cell is in mitosis or as a method of oncosuppression that prevents potentially tumorigenic cells from dividing.[6] This oncosuppression is accomplished by initiating a form of cell death such as apoptosis or necrosis or by inducing cellular senescence[6].

Mechanism to prevent cancer development

One usage of the term mitotic catastrophe is to describe an oncosuppressive mechanism (i.e. a mechanism to prevent the proliferation of cancerous cells and the develop of tumors) that occurs when cells undergo and detect a defective mitosis has occurred[7]. This definition of this mechanism has been described by the International Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death[8][7]. Under this definition, cells that undergo mitotic catastrophe either senesce and stop dividing or undergo a regulated form of cell death during mitosis or another form of cell death in the next G1 phase of the cell cycle[7][6]. The function of this mechanism is to prevent cells from accruing genomic instability which can lead to tumorigenesis[6][8].

When the cell undergoes cell death during mitosis this is known as mitotic death[6]. This is characterized by high levels of cyclin B1 still present in the cell at the time of cell death indicating the cell never finished mitosis[6]. Mitotic catastrophe can also lead to the cell being fated for cell death by apoptosis or necrosis following interphase of the cell cycle[6]. However, the timing of cell death can vary from hours after mitosis completes to years later which has been witnessed in human tissues treated with radiotherapy[6]. The least common outcome of mitotic catastrophe is senescence in which the cell stops dividing and enters a permanent cell cycle arrest that prevents the cell from proliferating any further[6].

Mechanism of cellular death

Another usage of the term mitotic catastrophe is to describe a mode of cell death that occurs during mitosis[5]. This cell death can occur due to an accumulation of DNA damage in the presence of improperly functioning DNA structure checkpoints or an improperly functioning spindle assembly checkpoint[5]. Cells that undergo mitotic catastrophe death can lack activation of pathways of the traditional death pathways such as apoptosis[9]. While more recent definitions of mitotic catastrophe do not use it to describe a bona fide cell death mechanism, some publications describe it as a mechanism of cell death[7][9].

Causes

Prolonged spindle assembly checkpoint activation

Cells have a mechanism to prevent improper segregation of chromosomes known as the spindle assembly checkpoint or mitotic checkpoint[6]. The spindle assembly checkpoint verifies that mitotic spindles have properly attached to the kinetochores of each pair of chromosomes before the chromosomes segregate during cell division[8]. If the mitotic spindles are not properly attached to the kinetochores then the spindle assembly checkpoint will prevent the transition from metaphase to anaphase[8]. This mechanism is important to ensure that the DNA within the cell is divided equally between the two daughter cells [6]. When the spindle assembly checkpoint is activated, it arrests the cell in mitosis until all chromosomes are properly attached and aligned[6]. If the checkpoint is activated for a prolonged period it can lead to mitotic catastrophe[6].

Prolonged activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint inhibits the anaphase promoting complex[10]. Normally, activation of the anaphase promoting complex leads to the separation of sister chromatids and the cell exiting mitosis[11]. The mitotic checkpoint complex acts as a negative regulator of the anaphase promoting complex[11]. Unattached kinetochores promote the formation of the mitotic checkpoint complex which is composed of four different proteins known as Mad2, Cdc20, BubR1, and Bub3 in humans[11]. When the mitotic checkpoint complex is formed, it binds to the anaphase promoting complex and prevents its ability to promote cell cycle progression[11].

Errors in mitosis

Some cells can have an erroneous mitosis yet survive and undergo another cell division which puts the cell at a higher likelihood to undergo mitotic catastrophe[6]. For instance, cells can undergo a process called mitotic slippage where cells exit mitosis to early before the process of mitosis is finished[12]. In this case, the cell finishes mitosis in the presence of spindle assembly checkpoint signaling which would normally prevent the cell from exiting mitosis[6]. This phenomenon is caused by improper degradation of cyclin B1 and can result in chromosome missegregation events[6]. Cyclin B1 is a major regulator of the cell cycle and guides the cells progression from G2 to M phase[13]. Cyclin B1 works with its binding partner CDK1 to control this progression and the complex is known as the mitotic promoting factor[13]. While the mitotic promoting factor is utilized to guide the cells entry into mitosis, its destruction also guides the cells exit from mitosis[13]. Normally, cyclin B1 degradation is initiated by the anaphase promoting complex after all of the kinetochores have been properly attached by mitotic spindle fibers[13]. However, when cyclin B1 levels are degraded to fast this can result in the cell exiting mitosis prematurely resulting in potential mitotic errors including missegregation of chromosomes[13].

Tetraploid or otherwise aneuploid cells are at higher risk of mitotic catastrophe[14]. Tetraploid cells are cells that have duplicated their genetic material, but have not undergo cytokinesis to split into two daughter cells and thus remain as one cell[15]. Aneuploid cells are cells that have an incorrect number of chromosomes including whole additions of chromosomes or complete losses of chromosomes[16]. Cells with an abnormal number of chromosomes are more likely to have chromosome segregation errors that result in mitotic catastrophe[14]. Cells that become aneuploid often are prevented from further cell growth and division by the activation of tumor suppressor pathways such as p53 which drives the cell to a non-proliferating state known as cellular senescence[14]. Given that aneuploid cells can often become tumorigenic, this mechanism prevents the propagation of these cells and thus prevents the development of cancers in the organism[6].

Cells that undergo multipolar divisions, or in other words split into more than 2 daughter cells, are at a higher risk of mitotic catastrophe as well[6]. While many of the progeny of multipolar divisions do not survive do to highly imbalanced chromosome numbers, most of the cells that survive and undergo a subsequent mitosis are likely to experience mitotic catastrophe[6]. These multipolar divisions occur due to the presence of more than two centrosomes[17]. Centrosomes are cellular organelles that acts to organize the mitotic spindle assembly in the cell during mitosis and thus guide the segregation of chromosomes during mitosis[18]. Normally, cells will have two centrosomes that guide sister chromatids to opposite poles of the dividing cell[19]. However, when there are more than two centrosomes present in mitosis they can pull chromosomes in incorrect directions resulting in daughter cells that are inviable[15]. Many cancers have excessive numbers of centrosomes, but to prevent inviable daughter cells, the cancer cells have developed mechanisms to cluster their centrosomes.[15] When the centrosomes are clustered to two poles of the dividing cell, the chromosomes are segregated properly and two daughter cells are formed.[15]. Thus, cancers that are able to adapt to a higher number of centrosomes are able to are able to prevent mitotic catastrophe and propagate in the presence of their extra centrosomes[6].

DNA damage

High levels of DNA damage that are not repaired before the cell enters mitosis can result in a mitotic catastrophe[6]. Cells that have a compromised G2 checkpoint do not have the ability to prevent progression through the cell cycle even when there is DNA damage present in the cell's genome[6]. The G2 checkpoint normally functions to stop cells that have damaged DNA from progressing to mitosis[20]. The G2 checkpoint can be compromised if tumor suppressor p53 is no longer present in the cell[6]. The response to DNA damage present during mitosis is different from the response to DNA damage detected during the rest of the cell cycle[6]. Cells can detect DNA defects during the rest of the cell cycle and either repair them if possible or undergo apoptosis of senescence[6]. Given that when this happens the cell does not progress into mitosis it is not considered a mitotic catastrophe[6].

Mitotic catastrophe in cancer

Prevention of genomic instability

Genomic instability is one of the hallmarks of cancer cells and promotes genetic changes (both large chromosomal changes as well as individual nucleotide changes) in cancer cells which can lead to increased levels of tumor progression through genetic variation in the tumor cell.[21] Cancers with a higher level of genomic instability have been shown to have worse patient outcomes than those cancers which have lower levels of genomic instability[22]. Cells have gained mechanisms that resist increased genomic instability in cells[6]. Mitotic catastrophe is one way in which cells prevent the propagation of genomically unstable cells[6]. If mitotic catastrophe fails for cells whose genome has become unstable they can propagate uncontrollably and potentially become tumorigenic[8].

The level of genomic instability is different across cancer types with epithelial cancers being more genomically unstable than cancers of hematological or mesenchymal origin[23]. Mesothelioma, small-cell lung cancer, breast, ovarian, non-small cell lung cancer, and liver cancer exhibit high levels of genomic instability while acute lymphoblastic leukemia, myelodysplasia, and myeloproliferative disorder have lower levels of instability[23].

Anticancer therapeutics

Promotion of mitotic catastrophe in cancer cells is an area of cancer therapeutic research that has garnered interest and is seen as a potential target to overcome resistance developed to current chemotherapies[14]. Cancer cells have been found to be more sensitive to mitotic catastrophe induction than non-cancerous cells in the body[6]. Tumors cells often have inactivated the machinery that is required for apoptosis such as the p53 protein[14]. This is usually achieved by mutations in the p53 protein or by loss of the chromosome region that contains the genetic code for it[24]. p53 acts to prevent the propagation of tumor cells and is considered a major tumor suppressor protein[24]. p53 works by either halting progression through the cell cycle when uncontrolled cell division is sensed or it can promote cell death through apoptosis in the presence of irreparable DNA damage[24]. Mitotic catastrophe can occur in a p53 independent fashion and thus presents a therapeutic avenue of interest[14]. Furthermore, doses of DNA damaging drugs lower than lethal levels have been shown to induce mitotic catastrophe[14]. This would allow for administration of a drug while the patient has fewer side effects[6].

Cancer therapies can induce mitotic catastrophe by either damaging the cells DNA or inhibiting spindle assembly[14]. Drugs, known as spindle poisons, affect the polymerization or depolymerization of microtubule spindles and thus interfere with the correct formation of the mitotic spindles[14]. When this happens, the spindle assembly checkpoint becomes activated and the transition from metaphase to anaphase is inhibited[14].

| Drug | Approved uses / clinical trial phase / research use | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|

| Paclitaxel[14] | Approved use: AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma, breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and ovarian cancer[25] | Promotes microtuble spindle assembly and prevents the detachment of microtubles preventing the cell from properly entering or exiting mitosis.[26] |

| Docetaxel[14] | Approved use: Breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, stomach adenocarcinoma, and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma[27] | |

| Vinblastin[14] | Approved use: Breast cancer, Choriocarcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, mycosis fungoides, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, testicular germ cell tumors[28] | Depolymerizes microtubules[14] |

| Vinkristine[14] | Approved use: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, lymphomas, neuroblastoma, sarcomas, and central nervous system tumors[29] | |

| Monastrol[6] | Research use | EG5 Inhibitor which perturbs the movement of chromosomes during mitosis.[6] This perturbation results in cells dying in mitosis or in the subsequent interphase.[30] |

| ARRY-520 (Filanesib)[6] | Phase III clinical trial: multiple myeloma[30] | |

| VX-680[6] | Pre-clinical research [31] | AURKA / AURKB inhibitor which disrupts the movement of chromosomes and the cytoskeleton during mitosis |

| MLN8237[14] | Phase I clincial trial: pediatric recurrent atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors and pediatric advanced solid tumors

Failed clinical trial for adult lymphomas and lung cancer[32] |

See also

References

- ^ Galluzzi, Lorenzo; Vitale, Ilio; Aaronson, Stuart A.; Abrams, John M.; Adam, Dieter; Agostinis, Patrizia; Alnemri, Emad S.; Altucci, Lucia; Amelio, Ivano; Andrews, David W.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, Margherita; Antonov, Alexey V.; Arama, Eli; Baehrecke, Eric H.; Barlev, Nickolai A. (March 2018). "Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018". Cell Death & Differentiation. 25 (3): 486–541. doi:10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. ISSN 1476-5403.

- ^ Castedo, Maria; Perfettini, Jean-Luc; Roumier, Thomas; Andreau, Karine; Medema, Rene; Kroemer, Guido (April 2004). "Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition". Oncogene. 23 (16): 2825–2837. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. ISSN 1476-5594.

- ^ Vitale, Ilio; Galluzzi, Lorenzo; Castedo, Maria; Kroemer, Guido (June 2011). "Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (6): 385–392. doi:10.1038/nrm3115. ISSN 1471-0080.

- ^ Denisenko, Tatiana V.; Sorokina, Irina V.; Gogvadze, Vladimir; Zhivotovsky, Boris (January 2016). "Mitotic catastrophe and cancer drug resistance: A link that must to be broken". Drug Resistance Updates: Reviews and Commentaries in Antimicrobial and Anticancer Chemotherapy. 24: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2015.11.002. ISSN 1532-2084. PMID 26830311.

- ^ a b c Castedo, Maria; Perfettini, Jean-Luc; Roumier, Thomas; Andreau, Karine; Medema, Rene; Kroemer, Guido (April 2004). "Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition". Oncogene. 23 (16): 2825–2837. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207528. ISSN 1476-5594.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Vitale, Ilio; Galluzzi, Lorenzo; Castedo, Maria; Kroemer, Guido (June 2011). "Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (6): 385–392. doi:10.1038/nrm3115. ISSN 1471-0080.

- ^ a b c d Galluzzi, Lorenzo; Vitale, Ilio; Aaronson, Stuart A.; Abrams, John M.; Adam, Dieter; Agostinis, Patrizia; Alnemri, Emad S.; Altucci, Lucia; Amelio, Ivano; Andrews, David W.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, Margherita; Antonov, Alexey V.; Arama, Eli; Baehrecke, Eric H.; Barlev, Nickolai A. (March 2018). "Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018". Cell Death & Differentiation. 25 (3): 486–541. doi:10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4. ISSN 1476-5403.

- ^ a b c d e Mc Gee, Margaret M. (2015). "Targeting the Mitotic Catastrophe Signaling Pathway in Cancer". Mediators of Inflammation. 2015: 146282. doi:10.1155/2015/146282. ISSN 1466-1861. PMC 4600505. PMID 26491220.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Fu, Xiao; Li, Mu; Tang, Cuilian; Huang, Zezhi; Najafi, Masoud (December 2021). "Targeting of cancer cell death mechanisms by resveratrol: a review". Apoptosis: An International Journal on Programmed Cell Death. 26 (11–12): 561–573. doi:10.1007/s10495-021-01689-7. ISSN 1573-675X. PMID 34561763.

- ^ Sazonova, Elena V.; Petrichuk, Svetlana V.; Kopeina, Gelina S.; Zhivotovsky, Boris (2021-12-09). "A link between mitotic defects and mitotic catastrophe: detection and cell fate". Biology Direct. 16 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s13062-021-00313-7. ISSN 1745-6150. PMC 8656038. PMID 34886882.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Lara-Gonzalez, Pablo; Pines, Jonathon; Desai, Arshad (September 2021). "Spindle assembly checkpoint activation and silencing at kinetochores". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 117: 86–98. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.06.009. ISSN 1096-3634. PMC 8406419. PMID 34210579.

- ^ Sinha, Debottam; Duijf, Pascal H.G.; Khanna, Kum Kum (2019-01-02). "Mitotic slippage: an old tale with a new twist". Cell Cycle. 18 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1080/15384101.2018.1559557. ISSN 1538-4101. PMC 6343733. PMID 30601084.

- ^ a b c d e Ghelli Luserna di Rorà, Andrea; Martinelli, Giovanni; Simonetti, Giorgia (2019-11-26). "The balance between mitotic death and mitotic slippage in acute leukemia: a new therapeutic window?". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 12: 123. doi:10.1186/s13045-019-0808-4. ISSN 1756-8722. PMC 6880427. PMID 31771633.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Denisenko, Tatiana V.; Sorokina, Irina V.; Gogvadze, Vladimir; Zhivotovsky, Boris (January 2016). "Mitotic catastrophe and cancer drug resistance: A link that must to be broken". Drug Resistance Updates: Reviews and Commentaries in Antimicrobial and Anticancer Chemotherapy. 24: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2015.11.002. ISSN 1532-2084. PMID 26830311.

- ^ a b c d Ganem, Neil J; Storchova, Zuzana; Pellman, David (2007-04-01). "Tetraploidy, aneuploidy and cancer". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Chromosomes and expression mechanisms. 17 (2): 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.011. ISSN 0959-437X.

- ^ Ben-David, Uri; Amon, Angelika (January 2020). "Context is everything: aneuploidy in cancer". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 21 (1): 44–62. doi:10.1038/s41576-019-0171-x. ISSN 1471-0064. PMID 31548659.

- ^ Ogden, A; Rida, P C G; Aneja, R (August 2012). "Let's huddle to prevent a muddle: centrosome declustering as an attractive anticancer strategy". Cell Death and Differentiation. 19 (8): 1255–1267. doi:10.1038/cdd.2012.61. ISSN 1350-9047. PMC 3392635. PMID 22653338.

- ^ Bornens, Michel (2021-02-01). "Centrosome organization and functions". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. Centrosomal Organization and Assemblies ● Folding and Binding. 66: 199–206. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2020.11.002. ISSN 0959-440X.

- ^ Doxsey, Stephen; Zimmerman, Wendy; Mikule, Keith (June 2005). "Centrosome control of the cell cycle". Trends in Cell Biology. 15 (6): 303–311. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.008. ISSN 0962-8924. PMID 15953548.

- ^ Stark, George R.; Taylor, William R. (2004), Schönthal, Axel H. (ed.), "Analyzing the G2/M Checkpoint", Checkpoint Controls and Cancer: Volume 1: Reviews and Model Systems, Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, pp. 51–82, doi:10.1385/1-59259-788-2:051, ISBN 978-1-59259-788-8, retrieved 2022-11-26

- ^ Hanahan, Douglas (January 2022). "Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions". Cancer Discovery. 12 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. ISSN 2159-8290. PMID 35022204.

- ^ Andor, Noemi; Maley, Carlo C.; Ji, Hanlee P. (2017-05-01). "Genomic instability in cancer: Teetering on the limit of tolerance". Cancer research. 77 (9): 2179–2185. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1553. ISSN 0008-5472. PMC 5413432. PMID 28432052.

- ^ a b Pikor, Larissa; Thu, Kelsie; Vucic, Emily; Lam, Wan (2013). "The detection and implication of genome instability in cancer". Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 32 (3): 341–352. doi:10.1007/s10555-013-9429-5. ISSN 0167-7659. PMC 3843371. PMID 23633034.

- ^ a b c Kanapathipillai, Mathumai (2018-05-23). "Treating p53 Mutant Aggregation-Associated Cancer". Cancers. 10 (6): 154. doi:10.3390/cancers10060154. ISSN 2072-6694. PMC 6025594. PMID 29789497.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Paclitaxel". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ Zhu, Linyan; Chen, Liqun (2019-06-13). "Progress in research on paclitaxel and tumor immunotherapy". Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters. 24: 40. doi:10.1186/s11658-019-0164-y. ISSN 1425-8153. PMC 6567594. PMID 31223315.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Docetaxel - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2006-10-05. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ "Vinblastine Sulfate - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2022-11-29.

- ^ Triarico, Silvia; Romano, Alberto; Attinà, Giorgio; Capozza, Michele Antonio; Maurizi, Palma; Mastrangelo, Stefano; Ruggiero, Antonio (2021-04-16). "Vincristine-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (VIPN) in Pediatric Tumors: Mechanisms, Risk Factors, Strategies of Prevention and Treatment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (8): 4112. doi:10.3390/ijms22084112. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8073828. PMID 33923421.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Garcia-Saez, Isabel; Skoufias, Dimitrios A. (2021-02-01). "Eg5 targeting agents: From new anti-mitotic based inhibitor discovery to cancer therapy and resistance". Biochemical Pharmacology. 184: 114364. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114364. ISSN 0006-2952.

- ^ Rossari, Federico; Minutolo, Filippo; Orciuolo, Enrico (2018-06-20). "Past, present, and future of Bcr-Abl inhibitors: from chemical development to clinical efficacy". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 11 (1): 84. doi:10.1186/s13045-018-0624-2. ISSN 1756-8722. PMC 6011351. PMID 29925402.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mills, Christopher C.; Kolb, EA.; Sampson, Valerie B. (2017-12-01). "Review: Recent advances of cell cycle inhibitor therapies for pediatric cancer". Cancer research. 77 (23): 6489–6498. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2066. ISSN 0008-5472. PMC 5712276. PMID 29097609.