Pneumatosis: Difference between revisions

Little pob (talk | contribs) →External links: add ICD10 code |

added to copying some from emphysematous cystitis page |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

===Subcutaneous=== |

===Subcutaneous=== |

||

[[File:Subcutaneous emphysema abdomen arrows2.jpg|thumb|240px|[[CT scan]] of [[subcutaneous emphysema]].]] |

[[File:Subcutaneous emphysema abdomen arrows2.jpg|thumb|240px|[[CT scan]] of [[subcutaneous emphysema]].]] |

||

[[Subcutaneous emphysema]] is found in the deepest layer of the skin. [[Emphysematous cystitis]] is a condition of gas in the [[urinary bladder|bladder wall]]. On occasion this may give rise to secondary subcutaneous emphysema which has a poor prognosis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sadek AR, Blake H, Mehta A | title = Emphysematous cystitis with clinical subcutaneous emphysema | journal = International Journal of Emergency Medicine | volume = 4 | issue = 1 | pages = 26 | date = June 2011 | pmid = 21668949 | pmc = 3123544 | doi = 10.1186/1865-1380-4-26 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Subcutaneous emphysema]] found in the deepest layer of the skin. |

|||

===Abdominal=== |

===Abdominal=== |

||

Revision as of 18:50, 27 June 2019

| Pneumatosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Emphysema |

| |

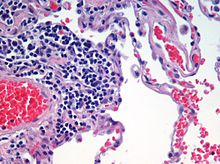

| Low magnification micrograph of pneumatosis intestinalis in bowel wall. | |

Pneumatosis, also known as emphysema, is the abnormal presence of air or other gas within tissues.

In the lungs, emphysema involves enlargement of the distal airspaces,[1] and is a major feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Pneumoperitoneum (or peritoneal emphysema) is air or gas in the abdominal cavity, and is most commonly caused by a perforated abdominal viscus, Pneumatosis is also a frequent result of surgery. The term is from pneumat- + -osis.

By location

Pulmonary emphysema

Pulmonary emphysema, more usually called emphysema, is characterised by air-filled cavities or spaces, (pneumatoses) in the lung, that can vary in size and may be very large. The spaces are caused by the breakdown of the walls of the alveoli and they replace the spongy lung parenchyma. This reduces the total alveolar surface available for gas exchange leading to a reduction in oxygen supply for the blood.[2]

It is a typical feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a type of obstructive lung disease characterized by long-term breathing problems and poor airflow.[3][4] Even without COPD, the finding of pulmonary emphysema on chest CT confers a higher mortality in tobacco smokers.[5] In 2016 in the United States there were 6,977 deaths from emphysema – 2.2 per 100,000 of the population.[6]

There are three subtypes of pulmonary emphysema – centrilobular or centriacinar, panlobular or panacinar, and paraseptal or distal acinar emphysema, related to the anatomy of the lobules of the lung.[7][8] These are not associated with fibrosis (scarring). A fourth type known as irregular emphysema involves the acinus irregularly and is associated with fibrosis.[8]

Though the subtypes can be seen on imaging they are not well-defined clinically.[9]

Centrilobular emphysema also called centriacinar emphysema, affects the centrilobular portion of the lung, the area around the terminal bronchiole, and the first respiratory bronchiole, and can be seen on imaging as an area around the tip of the visible pulmonary artery. Centrilobular emphysema is the most common type usually associated with smoking. The disease progresses from the centrilobular portion, leaving the lung parenchyma in the surrounding (perilobular) region preserved.[7] Usually the upper lobes of the lungs are affected.[8]

Panlobular emphysema, also called panacinar emphysema can involve the whole lung or mainly the lower lobes.[10] This type of emphysema is associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (A1AD or AATD),[10] and is not related to smoking.[9]

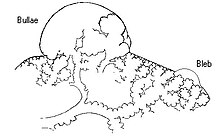

Paraseptal emphysema also called distal acinar emphysema relates to emphysematous change next to a pleural surface, or to a fissure.[9][11]

The cystic spaces known as blebs or bullae that form in paraseptal emphysema typically occur in just one layer beneath the pleura. This distinguishes it from the honeycombing of small cystic spaces seen in fibrosis that typically occurs in layers.[11]

When the subpleural bullae are significant the emphysema is called bullous emphysema. Bullae can become extensive and combine to form giant bullae. These can be large enough to take up a third of a hemithorax, compress the lung parenchyma, and cause displacement. The emphysema is now termed giant bullous emphysema, more commonly called vanishing lung syndrome due to the compressed parenchyma.[12]

HIV associated emphysema

Classic lung diseases are a complication of HIV/AIDS with emphysema being a source of disease. HIV is cited as a risk factor for the development of emphysema regardless of smoking status. HIV associated emphysema occurs over a much shorter time than that associated with smoking. It is thought that an understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the triggering of HIV associated emphysema may help in the understanding of the mechanisms of the development of smoking-related emphysema.[13]

CPFE

Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is a rare syndrome that shows upper-lobe emphysema, together with lower-lobe interstitial fibrosis. This is diagnosed by CT scan.[14]

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is a collection of air outside of the normal air space of the pulmonary alveoli, found instead inside the connective tissue of the peribronchovascular sheaths, interlobular septa, and visceral pleura.

Congenital lobar emphysema

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE), also known as congenital lobar overinflation and infantile lobar emphysema,[15] is a neonatal condition associated with enlarged air spaces in the lungs of newborn infants. It is diagnosed around the time of birth or in the first 6 months of life, occurring more often in boys than girls. CLE affects the upper lung lobes more than the lower lobes, and the left lung more often than the right lung.[16] CLE is defined as the hyperinflation of one or more lobes of the lung due to the partial obstruction of the bronchus. This causes symptoms of pressure on the nearby organs.[17]Although CLE may be caused by the abnormal development of bronchi, or compression of airways by nearby tissues, no cause is identified in half of cases.[16]

Parenchymal focalities

A focal lung pneumatosis, is a solitary volume of air in the lung that is larger than alveoli. A focal lung pneumatosis can be classified by its wall thickness:

- A pulmonary bleb or bulla has a wall thickness of less than 1 mm[18] Blebs and bullae are also known as a focal regions of emphysema.[19]

- A pulmonary cyst has a wall thickness of up to 4 mm.[18] A minimum wall thickness of 1 mm has been suggested,[18] but thin-walled pockets may be included in the definition as well.[20] Pulmonary cysts are not associated with either smoking or emphysema.[21]

- A cavity has a wall thickness of more than 4 mm[18]

The terms above, when referring to sites other than the lungs, often imply fluid content.

Other thoracic

- Pneumothorax, air or gas in the pleural space

- Pneumomediastinum, air or gas in the mediastinum

- Also called mediastinal emphysema or pneumatosis/emphysema of the mediastinum

Subcutaneous

Subcutaneous emphysema is found in the deepest layer of the skin. Emphysematous cystitis is a condition of gas in the bladder wall. On occasion this may give rise to secondary subcutaneous emphysema which has a poor prognosis.[22]

Abdominal

- Pneumoperitoneum (or peritoneal emphysema), air or gas in the abdominal cavity. The most common cause is a perforated abdominal viscus, generally a perforated peptic ulcer, although any part of the bowel may perforate from a benign ulcer, tumor or abdominal trauma.

- Pneumatosis intestinalis, air or gas cysts in the bowel wall

- Gastric pneumatosis, air or gas cysts in the stomach wall

Joints

Pneumarthrosis is the presence of air in a joint. Its presentation on radiography is a radiolucent cleft often called a vacuum phenomena.[23] Pneumarthrosis is associated with osteoarthritis and spondylosis.[24]

Pneumarthrosis is a common normal finding in shoulders[23] as well as in sternoclavicular joints.[25] It is believed to be a cause of the sounds of joint cracking.[24] It is also a common normal postoperative finding at least in spinal surgery.[26] In fact, pneumarthrosis is extremely rare in conjunction with fluid or pus in a joint, and its presence can therefore practically exclude infection.[24]

-

X-ray of a hip with prosthesis and pneumarthrosis, in this case aseptic.

-

A vacuum sign is a normal finding on shoulder X-rays.

References

- ^ page 64 in: Adrian Shifren (2006). The Washington Manual Pulmonary Medicine Subspecialty Consult, Washington manual subspecialty consult series. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781743761.

- ^ Saladin, K (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 650. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ Algusti, Alvar G.; et al. (2017). "Definition and Overview". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). pp. 6–17.

- ^ Roversi, Sara; Corbetta, Lorenzo; Clini, Enrico (5 May 2017). "GOLD 2017 recommendations for COPD patients: toward a more personalized approach". COPD Research and Practice. 3. doi:10.1186/s40749-017-0024-y.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Diedtra Henderson (2014-12-16). "Emphysema on CT Without COPD Predicts Higher Mortality Risk". Medscape.

- ^ "FastStats". www.cdc.gov. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ a b Takahashi, M; Fukuoka, J (2008). "Imaging of pulmonary emphysema: a pictorial review". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 3: 193–204 – via PMID 18686729.

- ^ a b c Kumar, V (2018). Robbins Basic Pathology. Elsevier. pp. 498–499. ISBN 9780323353175.

- ^ a b c Smith, B (January 2014). "Pulmonary emphysema subtypes on computed tomography: the MESA COPD study". Am J Med. 127 – via PMID 24384106.

- ^ a b Weerakkody, Yuranga. "Panlobular emphysema | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Chest". Radiology assistant. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Sharma, N; Justaniah, AM (August 2009). "Vanishing lung syndrome (giant bullous emphysema):CT findings in 7 patients and a literature review". J Thoracic Imaging. 24: 227–230. PMID 19704328.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Petrache, I (May 2008). "HIV associated pulmonary emphysema: a review of the literature and inquiry into its mechanism". Thorax. 63: 463–9 – via PMID 18443163.

- ^ Wand, O; Kramer, MR (January 2018). "[THE SYNDROME OF COMBINED PULMONARY FIBROSIS AND EMPHYSEMA - CPFE]". Harefuah. 157: 28–33 – via PMID 29374870.

- ^ "UpToDate: Congenital lobar emphysema". Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ a b Guidry, Christopher; McGahren, Eugene D. (June 2012). "Pediatric Chest I". Surgical Clinics of North America. 92 (3): 615–643. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2012.03.013. PMID 22595712.

- ^ Demir, Omer (May 2019). "Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnosis and treatment options". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 14: 921–928 – via PMID 31118601.

- ^ a b c d Dr Daniel J Bell and Dr Yuranga Weerakkody. "Pulmonary cyst". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- ^ Gaillard, Frank. "Pulmonary bullae | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Araki, Tetsuro; Nishino, Mizuki; Gao, Wei; Dupuis, Josée; Putman, Rachel K; Washko, George R; Hunninghake, Gary M; O'Connor, George T; Hatabu, Hiroto (2015). "Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT: are they part of aging change or of clinical significance?". Thorax. 70 (12): 1156–1162. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207653. ISSN 0040-6376.

- ^ Araki, Tetsuo. "Pulmonary cysts identified on chest CT:are they part of ageing change or of clinical significance" (PDF). Retrieved 19 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Sadek AR, Blake H, Mehta A (June 2011). "Emphysematous cystitis with clinical subcutaneous emphysema". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 4 (1): 26. doi:10.1186/1865-1380-4-26. PMC 3123544. PMID 21668949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Abhijit Datir; et al. "Vacuum phenomenon in shoulder". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ^ a b c Page 60 in: Harry Griffiths (2008). Musculoskeletal Radiology. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420020663.

- ^ Restrepo, Carlos S.; Martinez, Santiago; Lemos, Diego F.; Washington, Lacey; McAdams, H. Page; Vargas, Daniel; Lemos, Julio A.; Carrillo, Jorge A.; Diethelm, Lisa (2009). "Imaging Appearances of the Sternum and Sternoclavicular Joints". RadioGraphics. 29 (3): 839–859. doi:10.1148/rg.293055136. ISSN 0271-5333.

- ^ Mall, J C; Kaiser, J A (1987). "The usual appearance of the postoperative lumbar spine". RadioGraphics. 7 (2): 245–269. doi:10.1148/radiographics.7.2.3448634. ISSN 0271-5333.