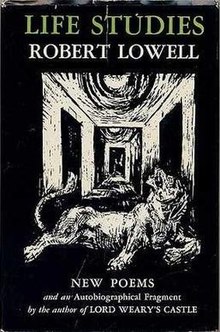

Life Studies

First edition | |

| Author | Robert Lowell |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Frank Parker |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus & Giroux |

Publication date | 1959 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Preceded by | The Mills of The Kavanaughs |

| Followed by | Imitations |

Life Studies is the fourth book of poems by Robert Lowell. Most critics (including Helen Vendler, Steven Gould Axelrod, Adam Kirsch, and others) consider it one of Lowell's most important books, and the Academy of American Poets named it one of their Groundbreaking Books.[1] Helen Vendler called Life Studies Lowell's "most original book."[2] It won the National Book Award for Poetry in 1960.[3]

Publication

[edit]Life Studies was first published in London by Faber & Faber. This was to allow for it to be entered for selection by the Poetry Book Society, one condition being that the first edition must be British. Because of the rush to release the book in Britain, the British first edition does not include the "91 Revere Street" section. The first American edition was published in 1959 by Farrar, Straus and Cudahy based in New York City.

Content

[edit]

Part I of the book contains four poems that are similar in style and tone to the poems of Lowell's previous books, The Mills of the Kavanaughs and Lord Weary's Castle. They are well-polished, formal in their use of meter and rhyme, and fairly impersonal. This first section can be interpreted as a transition section, signaling Lowell's move away from Catholicism, as evidenced by the book's first poem, "Beyond the Alps," as well as a move away from the traditional, dense, more impersonal style of poetry that characterized Lowell's writing while he was still a practicing Catholic and closely associated with New Critical poets like Allen Tate and John Crowe Ransom. Notably, at a 1963 poetry reading at the Guggenheim Museum, Lowell introduced his reading of "Beyond the Alps" by stating that, "[the poem was] a declaration of my faith or lack of faith."[4]

Part II contains only one piece which is titled "91 Revere Street" and is the first (and only) significant passage of prose to appear in one of Lowell's books of poems. It centers, with intricate detail, on Lowell's childhood when his family was living in Boston's Beacon Hill neighborhood at 91 Revere Street. The piece, which is the longest one in the book, also focuses on his parents' marriage as well as young Lowell's relationship with his parents, other relatives, and his childhood peers. Notable characters in the piece include Lowell's great-grandfather Mordecai Myers and his father's Navy buddy, Commander Billy Harkness.

"91 Revere Street" also sets the stage for the portraits of his family members in the book's final section. According to Ian Hamilton, one of Lowell's unofficial biographers, this section was begun as a potentially therapeutic assignment suggested by Lowell's therapist. Lowell also stated that this prose exercise led him to the stylistic breakthrough of the poems in Part IV.[5] The apartment at 91 Revere Street in Beacon Hill still exists and is noted by a Boston historical marker as Lowell's childhood home.

Part III contains odes to four writers: Hart Crane, Delmore Schwartz, George Santayana, and Ford Madox Ford. At the time that Lowell published these poems, only Schwartz was still alive, and with the exception of Hart Crane, Lowell knew all of them personally and considered them to be mentors at different stages of his career.

Part IV contains the majority of the book's poems and is given the subheading of "Life Studies." These poems are the ones that critics refer to as "confessional." These "confessional" poems are the ones that document Lowell's struggle with mental illness and include pieces like "Skunk Hour", "Home After Three Months Away" and "Waking in the Blue." However, the majority of the poems in this section revolve around Lowell's family with a particular emphasis on the troubled marriage of his parents (as Lowell established in Part II). Lowell's maternal grandfather, Arthur Winslow, also receives significant attention in poems like "Dunbarton" and "Grandparents."

Critical response

[edit]M. L. Rosenthal wrote a review of Life Studies, entitled "Poetry as Confession" which first applied the term "confessional" to Lowell's approach in Life Studies, and led to the name of the school of Confessional poetry. For this reason, Life Studies is viewed as one of the first confessional books of poetry, although some poets and poetry critics such as Adam Kirsch[6] and Frank Bidart[7] question the accuracy of the confessional label. However, no one questions the book's lasting influence. The prominent poet Stanley Kunitz noted this tremendous influence when he wrote, in a 1985 essay, "Life Studies. . .[was] perhaps the most influential book of modern verse since T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land." [8]

In a 1962 interview with Peter Orr, Sylvia Plath specifically cited Lowell's Life Studies as having had a profound influence over the poetry she was writing at that time (and which her husband would publish posthumously as Ariel a few years later), stating, "I've been very excited by what I feel is the new breakthrough that came with, say, Robert Lowell's Life Studies, this intense breakthrough into very serious, very personal, emotional experience which I feel has been partly taboo. Robert Lowell's poems about his experience in a mental hospital, for example, interested me very much."[9]

The website for the Academy for American Poets states that, "Lowell's work in Life Studies had an especially profound impact that is discernible not only in the poetry of his direct contemporaries, such as Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, but also in the treatment of biographical detail by countless poets who followed."[10] John Thompson in The Kenyon Review supports this contention stating that, "For these poems, the question of propriety no longer exists. They have made a conquest: what they have won is a major expansion of the territory of poetry."[11]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Poets.org". Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Helen Vendler Lecture on Lowell. Poets.org. 18 November 2009

- ^

"National Book Awards – 1960". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

(With acceptance speech by Lowell and essay by Dilruba Ahmed from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - ^ Lowell, Robert and John Berryman. Guggenheim Poetry Reading. New York: Academy of American Poets Archive, 1963. 88 minutes.

- ^ Hamilton, Ian. Robert Lowell: A Life. New York: Faber & Faber, 1982.

- ^ Kirsch, Adam, The Wounded Surgeon: Confession and Transformation in Six American Poets New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- ^ Bidart, Frank. "On Confessional Poetry." The Collected Poems of Robert Lowell. 2003.

- ^ Kunitz, Stanley. Next-to-Last Things: New Poems and Essays. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1985.

- ^ Orr, Peter, ed. "The Poet Speaks - Interviews with Contemporary Poets Conducted by Hilary Morrish, Peter Orr, John Press and Ian Scott-Kilvert". London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.[1]

- ^ "Groundbreaking Poets: Life Studies. No author listed". Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ Thompson, John, "Two Poets",Kenyon Review 21 (1959) pages 482 – 490.