Ancient North Eurasian

In archaeogenetics, the term Ancient North Eurasian (generally abbreviated as ANE) is the name given to an ancestral component that represents a lineage ancestral to the people of the Mal'ta–Buret' culture and populations closely related to them, such as from Afontova Gora and the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site, and populations descended from them.[1] ANE ancestry developed from a sister lineage of West-Eurasians with significant admixture from early East Asians.[2]

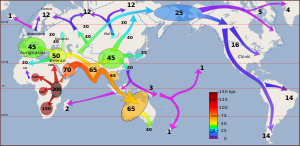

ANE ancestry has spread throughout Eurasia and the Americas in various migrations since the Upper Paleolithic, and more than half of the world's population today derives between 5 to 40% of their genomes from the Ancient North Eurasians.[3] Significant ANE ancestry can be found in the indigenous peoples of the Americas, as well as in regions of Europe, South Asia, Central Asia, and Siberia. It has been suggested that their mythology may have included a narrative, found in both Indo-European and some Native American fables, in which a dog guards the path to the afterlife.[4]

Genetic studies

The ANE lineage is defined by association with the MA-1, or "Mal'ta boy", the remains of an individual who lived during the Last Glacial Maximum, 24,000 years ago in central Siberia, discovered in the 1920s.

Ancient North Eurasians are described as a lineage "which is deeply related to Paleolithic/Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe", meaning that they diverged from Paleolithic Europeans a long time ago. Ancient North Eurasians originated either in Europe or in the Middle East.[5][6][7][8] Ancient North Eurasians also had varying degrees of admixture from an ancient East Asian-related population, such as the Tianyuan Man. Sikora et al. (2019) found that the oldest ANE-associated Yana RHS sample (31,600 BP) in Northeastern Siberia "can be modelled as early West Eurasian with an approximately 22% contribution from early East Asians" suggesting early contact in Northeastern Siberia.[9][a]

Populations genetically similar to MA-1 were an important genetic contributor to Native Americans, Europeans, Ancient Central Asians, South Asians, and some East Asian groups, in order of significance.[10] Lazaridis et al. (2016:10) note "a cline of ANE ancestry across the east-west extent of Eurasia."[10] The ancient Bronze-age-steppe Yamnaya and Afanasevo cultures were found to have a noteworthy ANE component at ~25% (some studies estimated a higher percentage at nearly ~50%).[11] According to Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018 between 14% and 38% of Native American ancestry may originate from gene flow from the Mal'ta–Buret' people (ANE). This difference is caused by the penetration of posterior Siberian migrations into the Americas, with the lowest percentages of ANE ancestry found in Eskimos and Alaskan Natives, as these groups are the result of migrations into the Americas roughly 5,000 years ago.[12] Estimates for ANE ancestry among first wave Native Americans show higher percentages,[13] such as 42% for those belonging to the Andean region in South America.[13] The other gene flow in Native Americans (the remainder of their ancestry) was of East Asian origin.[6] Gene sequencing of another south-central Siberian people (Afontova Gora-2) dating to approximately 17,000 years ago, revealed similar autosomal genetic signatures to that of Mal'ta boy-1, suggesting that the region was continuously occupied by humans throughout the Last Glacial Maximum.[6]

Genomic studies also indicate that the ANE component was introduced to Western Europe by people related to the Yamnaya culture, long after the Paleolithic.[11][1] It is reported in modern-day Europeans (10%–20%).[11][1] Additional ANE ancestry is found in European populations through Paleolithic interactions with Eastern European Hunter-Gatherers, which resulted in populations such as Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers.[14]

Groups partially derived from the Ancient North Eurasians

Eastern Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) is a lineage which derived significant ancestry from ANE, ranging between 9% to up to 75%, with the remaining ancestry from a group more closely related to, but distinct from, Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs).[10][16] It is represented by two individuals from Karelia, one of Y-haplogroup R1a-M417, dated c. 8.4 kya, the other of Y-haplogroup J, dated c. 7.2 kya; and one individual from Samara, of Y-haplogroup R1b-P297, dated c. 7.6 kya. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHG) and EHG lineages merged in Eastern Europe, accounting for early presence of ANE-derived ancestry in Mesolithic Europe. Evidence suggests that as Ancient North Eurasians migrated West from Eastern Siberia, they absorbed Western Hunter-Gatherers and other West Eurasian populations as well.[17]

Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer (SHG) is represented by several individuals buried at Motala, Sweden ca. 6000 BC. They were descended from Western Hunter-Gatherers who initially settled Scandinavia from the south, and later populations of EHG who entered Scandinavia from the north through the coast of Norway.[18][11][19][14][20]

Ancient Beringian/Ancestral Native American are specific archaeogenetic lineages, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago.[21] The AB lineage diverged from the Ancestral Native American (ANA) lineage about 20,000 years ago.

West Siberian Hunter-Gatherer (WSHG) are a specific archaeogenetic lineage, first reported in a genetic study published in Science in September 2019. WSGs were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% to 38% East Asian ancestry.[13][22]

Western Steppe Herders (WSH) is the name given to a distinct ancestral component that represents descent closely related to the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe.[b] This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya ancestry or Steppe ancestry.[5]

Late Upper Paeolithic Lake Baikal - Ust'Kyakhta-3 (UKY) 14,050-13,770 BP were mixture of 30% ANE ancestry and 70% East Asian ancestry.[24]

Lake Baikal Holocene - Baikal Eneolithic (Baikal_EN) and Baikal Early Bronze Age (Baikal_EBA) derived 6.4% to 20.1% ancestry from ANE, while rest of their ancestry was derived from East Asians. Fofonovo_EN near by Lake Baikal were mixture of 12-17% ANE ancestry and 83-87% East Asian ancestry.[25]

Jōmon people, the pre-Neolithic population of Japan, mainly derived their ancestry from East Asian lineages, but also received geneflow from the ANE-related "Ancient North Siberians" (represented by samples from the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site) prior to the migration from the Asian mainland to the Japanese archipelago. Jōmon ancestry is still found among the inhabitants of present-day Japan: most markedly among the Ainu people, who are considered the direct descendants of the Jōmon people, and to a small, but significant degree among the majority of the Japanese population.[26][27]

Evolution of blond hair

Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the KITLG gene are associated with blonde hair color in various human populations. One of these polymorphisms is associated with blond hair.[28][29][30][31] The earliest known individual with this allele is a female south-central Siberian ANE individual from Afontova Gora 3 site, which is dated to 16130-15749 BCE.[32] Mathieson, et al (2018) thus argued that this gene originated in the Ancient North Eurasian population.[33]

Geneticist David Reich said that the KITLG gene for blond hair probably entered continental Europe in a population migration wave from the Eurasian steppe, by a population carrying substantial Ancient North Eurasian ancestry.[34] Hanel and Carlberg (2020) likewise report that populations bearing Ancient North Eurasian ancestry were responsible for contributing this gene to Europeans.[35]

Comparative mythology

Since the term 'Ancient North Eurasian' refers to a genetic bridge of connected mating networks, scholars of comparative mythology have argued that they probably shared myths and beliefs that could be reconstructed via the comparison of stories attested within cultures that were not in contact for millennia and stretched from the Pontic–Caspian steppe to the American continent.[4]

For instance, the mytheme of the dog guarding the Otherworld possibly stems from an older Ancient North Eurasian belief, as suggested by similar motifs found in Indo-European, Native American and Siberian mythology. In Siouan, Algonquian, Iroquoian, and in Central and South American beliefs, a fierce guard dog was located in the Milky Way, perceived as the path of souls in the afterlife, and getting past it was a test. The Siberian Chukchi and Tungus believed in a guardian-of-the-afterlife dog and a spirit dog that would absorb the dead man's soul and act as a guide in the afterlife. In Indo-European myths, the figure of the dog is embodied by Cerberus, Sarvarā, and Garmr. In Zoroastrianism, two four-eyed dogs guard the bridge to the afterlife called Chinvat Bridge. Anthony and Brown note that it might be one of the oldest mythemes recoverable through comparative mythology.[4]

A second canid-related series of beliefs, myths and rituals connected dogs with healing rather than death. For instance, Ancient Near Eastern and Turkic-Kipchaq myths are prone to associate dogs with healing and generally categorised dogs as impure. A similar myth-pattern is assumed for the Eneolithic site of Botai in Kazakhstan, dated to 3500 BC, which might represent the dog as absorber of illness and guardian of the household against disease and evil. In Mesopotamia, the goddess Nintinugga, associated with healing, was accompanied or symbolized by dogs. Similar absorbent-puppy healing and sacrifice rituals were practiced in Greece and Italy, among the Hittites, again possibly influenced by Near Eastern traditions.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Flegontov et al. 2016.

- ^ Vallini et al. 2022, Supplementary Information, p. 17: "Paleolithic Siberian populations younger than 40 ky are consistently described as a mix of European and East Asian ancestries".

- ^ Reich 2018, p. 81

- ^ a b c d Anthony & Brown 2019, pp. 104–106.

- ^ a b Jeong et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c Raghavan et al. 2013.

- ^ Balter 2013.

- ^ Yang, Melinda A. (2022-01-06). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics. 2 (1). doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001. ISSN 2770-5005.

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A. (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene". Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

- ^ a b c Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ^ a b c d Haak et al. 2015.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018.

- ^ a b c Wong et al. 2017.

- ^ a b Günther et al. 2018.

- ^ Burenhult, Göran [in Swedish] (2000). Die ersten Menschen [The first people] (in German). Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8289-0741-6.

- ^ Wang 2019.

- ^ Mathieson et al. 2018.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2014.

- ^ Mathieson 2015.

- ^ Mittnik 2018.

- ^ Moreno-Mayar et al. 2018.

- ^ Narasimhan 2019.

- ^ Jeong et al. 2018.

- ^ Yu et al. 2020.

- ^ Jeong et al. 2020.

- ^ Osada & Kawai 2021.

- ^ Cooke, Niall P.; Mattiangeli, Valeria; Cassidy, Lara M.; Okazaki, Kenji; Stokes, Caroline A.; Onbe, Shin; Hatakeyama, Satoshi; Machida, Kenichi; Kasai, Kenji; Tomioka, Naoto; Matsumoto, Akihiko (2021). "Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations". Science Advances. 7 (38): eabh2419. Bibcode:2021SciA....7H2419C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh2419. PMC 8448447. PMID 34533991. "This affinity is still detectable even if we replace these reference populations with the other Southeast and East Asians (table S6), supporting gene flow between the ancestors of Jomon and Ancient North Siberians, a population widespread in North Eurasia before the LGM (19)."

- ^ Hartz, Patricia. "KIT LIGAND; KITLG". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

- ^ Khan, Razib. "KITLG makes you white skinned?". Discover Magazine.

- ^ "P21583". Uniprot.

- ^ Guenther et al. 2014.

- ^ Evans, Gavin (2019). Skin Deep: Dispelling the Science of Race (1 ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 139. ISBN 9781786076236.| "Japanese research in 2006 found that the genetic mutation that prompted the evolution of blond hair dates to the ice age that happened around 11,000 years ago. Since then, the 17,000-year-old remains of a blond- haired North Eurasian hunter-gatherer have been found in eastern Siberia, suggesting an earlier origin."

- ^ Mathieson et al. 2018 "Supplementary Information page 52: "The derived allele of the KITLG SNP rs12821256 that is associated with – and likely causal for blond hair in Europeans7,8 is present in one hunter-gatherer from each of Samara, Motala and Ukraine (I0124, I0014 and I1763), as well as several later individuals with Steppe ancestry. Since the allele is found in populations with EHG but not WHG ancestry, it suggests that its origin is in the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) population. Consistent with this, we observe that the earliest known individual with the derived allele (supported by two reads) is the ANE individual Afontova Gora 3,6 which is directly dated to 16130-15749 cal BCE (14710±60 BP, MAMS-27186: a previously unpublished date that we newly report here). We cannot determine the status of rs12821256 in Afontova Gora 2 and MA-1 due to lack of sequence coverage at this SNP.9"

- ^ Reich, David (2018). Who We are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198821250. "The earliest known example of the classic European blond hair mutation is in an Ancient North Eurasian from the Lake Baikal region of eastern Siberia from seventeen thousand years ago. The hundreds of millions of copies of this mutation in central and western Europe today likely derive from a massive migration of people bearing Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, an event that is related in the next chapter."

- ^ Carlberg & Hanel 2020.

Notes

- ^ Vallini et al. (2022) model Yana RHS and Mal'ta as a mixture of a sister lineage of early West Eurasians (Kostenki14, Sunghir) with a sister lineage of early East Asians (Tianyuan). Mal'ta can either be modeled as derived from the same admixed source population as Yana RHS, or originating from a different admixture event with similar proportions of admixture as in Yana RHS.

- ^ "Recent paleogenomic studies have shown that migrations of Western steppe herders (WSH) beginning in the Eneolithic (ca. 3300–2700 BCE) profoundly transformed the genes and cultures of Europe and central Asia... The migration of these Western steppe herders (WSH), with the Yamnaya horizon (ca. 3300–2700 BCE) as their earliest representative, contributed not only to the European Corded Ware culture (ca. 2500–2200 BCE) but also to steppe cultures located between the Caspian Sea and the Altai-Sayan mountain region, such as the Afanasievo (ca. 3300–2500 BCE) and later Sintashta (2100–1800 BCE) and Andronovo (1800–1300 BCE) cultures."[23]

Bibliography

- Anthony, David W.; Brown, Dorcas R. (2019). "Late Bronze Age midwinter dog sacrifices and warrior initiations at Krasnosamarskoe, Russia". In Olsen, Birgit A.; Olander, Thomas; Kristiansen, Kristian (eds.). Tracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from archaeology and historical linguistics. Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78925-273-6.

- Balter, M. (25 October 2013). "Ancient DNA Links Native Americans With Europe". Science. 342 (6157): 409–410. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..409B. doi:10.1126/science.342.6157.409. PMID 24159019.

- Dolitsky, Alexander B.; Ackerman, Robert E.; Aigner, Jean S.; et al. (June 1985). "Siberian Paleolithic Archaeology: Approaches and Analytic Methods [and Comments and Replies]". Current Anthropology. 26 (3): 361–378. doi:10.1086/203280. S2CID 147371671.

- Carlberg, Carsten; Hanel, Andrea (2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 864–875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. PMID 32621306.

- Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; Zidkova, Anastassiya; Logacheva, Maria D.; et al. (11 February 2016). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 20768. arXiv:1508.03097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620768F. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

- Günther, Torsten; Malmström, Helena; Svensson, Emma M.; Omrak, Ayça; et al. (9 January 2018). "Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: Investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation". PLOS Biology. 16 (1): e2003703. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003703. PMC 5760011. PMID 29315301.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; et al. (2 March 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Guenther, Catherine A; Tasic, Bosiljka; Luo, Liqun; Bedell, Mary A; Kingsley, David M (July 2014). "A molecular basis for classic blond hair color in Europeans". Nature Genetics. 46 (7): 748–752. doi:10.1038/ng.2991. PMC 4704868. PMID 24880339.

- Jeong, Choongwon; Wilkin, Shevan; Amgalantugs, Tsend; Bouwman, Abigail S.; et al. (27 November 2018). "Bronze Age population dynamics and the rise of dairy pastoralism on the eastern Eurasian steppe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (48): E11248–E11255. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813608115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6275519. PMID 30397125.

- Jeong, Choongwon; Balanovsky, Oleg; Lukianova, Elena; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; et al. (June 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (6): 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- Jeong, Choongwon; Wang, Ke; Wilkin, Shevan; Taylor, William Timothy Treal; et al. (26 March 2020). "A dynamic 6,000-year genetic history of Eurasia's Eastern Steppe". Cell. 183 (4): 890–904.e29. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.03.25.008078. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-77BF-D. PMC 7664836. PMID 33157037. S2CID 214725595.

- Kanzawa-Kiriyama, Hideaki; Kryukov, Kirill; Jinam, Timothy A; Hosomichi, Kazuyoshi; et al. (February 2017). "A partial nuclear genome of the Jomons who lived 3000 years ago in Fukushima, Japan". Journal of Human Genetics. 62 (2): 213–221. doi:10.1038/jhg.2016.110. PMC 5285490. PMID 27581845.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Nadel, Dani; Rollefson, Gary; et al. (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Mittnik, Alissa; et al. (17 September 2014). "Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans". Nature. 513 (7518): 409–413. arXiv:1312.6639. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..409L. doi:10.1038/nature13673. hdl:11336/30563. PMC 4170574. PMID 25230663.

- Mathieson, Iain; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Songül; Posth, Cosimo; et al. (21 February 2018). "The genomic history of southeastern Europe" (PDF). Nature. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Mathieson, Iain (November 23, 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583). Nature Research: 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Mittnik, Alisa (January 30, 2018). "The genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region". Nature Communications. 9 (1). Nature Research: 442. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..442M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02825-9. PMC 5789860. PMID 29382937.

- Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Vinner, Lasse; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; et al. (7 December 2018). "Early human dispersals within the Americas" (PDF). Science. 362 (6419): eaav2621. Bibcode:2018Sci...362.2621M. doi:10.1126/science.aav2621. PMID 30409807. S2CID 53241760.

- Moreno-Mayar, J. Víctor; Potter, Ben A.; Vinner, Lasse; Steinrücken, Matthias; et al. (January 2018). "Terminal Pleistocene Alaskan genome reveals first founding population of Native Americans" (PDF). Nature. 553 (7687): 203–207. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..203M. doi:10.1038/nature25173. PMID 29323294. S2CID 4454580.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). American Association for the Advancement of Science: eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Raghavan, Maanasa; Skoglund, Pontus; Graf, Kelly E.; Metspalu, Mait; et al. (20 November 2013). "Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans". Nature. 505 (7481): 87–91. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...87R. doi:10.1038/nature12736. PMC 4105016. PMID 24256729.

- Osada, Naoki; Kawai, Yosuke (2021). "Exploring models of human migration to the Japanese archipelago using genome-wide genetic data". Anthropological Science. 129 (1): 45–58. doi:10.1537/ase.201215.

- Vallini, Leonardo; Marciani, Giulia; Aneli, Serena; Bortolini, Eugenio; et al. (2022). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (4). doi:10.1093/gbe/evac045.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao (February 4, 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions Eurasia". Nature Communications. 10 (1). Nature Research: 590. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

- Wong, Emily H.M.; Khrunin, Andrey; Nichols, Larissa; Pushkarev, Dmitry; et al. (January 2017). "Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations". Genome Research. 27 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1101/gr.202945.115. PMC 5204334. PMID 27965293.

- Yu, He; Spyrou, Maria A.; Karapetian, Marina; Shnaider, Svetlana; et al. (June 2020). "Paleolithic to Bronze Age Siberians Reveal Connections with First Americans and across Eurasia". Cell. 181 (6): 1232–1245.e20. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.037. PMID 32437661. S2CID 218710761.