Benty Grange hanging bowl

| Benty Grange hanging bowl | |

|---|---|

Reconstructed escutcheon design | |

| Material | Bronze, enamel |

| Discovered | 1848 Benty Grange farm, Monyash, Derbyshire, England 53°10′30″N 1°46′59″W / 53.174895°N 1.782923°W |

| Discovered by | Thomas Bateman |

| Present location | Weston Park Museum, Sheffield; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford |

| Registration | J93.1190; AN1893.276 |

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is a fragmentary Anglo-Saxon artefact from the seventh century AD. All that remains are two escutcheons: bronze frames that are usually circular and elaborately decorated, and that sit outside the rim or at the interior base of a hanging bowl. A third disintegrated soon after excavation, and no longer survives. The escutcheons were found in 1848 by the antiquary Thomas Bateman, while excavating a tumulus at the Benty Grange farm in western Derbyshire, and were undoubtedly buried as part of an entire hanging bowl. The grave had probably been looted by the time of Bateman's excavation, but still contained high-status objects suggestive of a richly furnished burial, including the hanging bowl and the Benty Grange helmet.

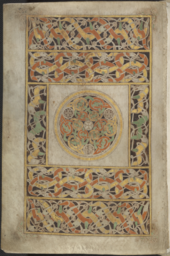

The surviving escutcheons are made of enamelled bronze and are 40 mm (1.6 in) in diameter. They show three dolphin-like creatures arranged in a circle, each biting the tail of the animal ahead of it. Their bodies and the background are made of enamel, likely all yellow, with the animals' outlines and eyes tinned or silvered, as are the borders of the escutcheons. Although three escutcheons from a hanging bowl at Faversham also contain dolphin-like creatures, the Benty Grange design is most closely parallelled by Insular manuscripts, particularly figures in the Durham Gospel Fragment and the Book of Durrow. Surviving illustrations of the third escutcheon show that it was of a different size and style, exhibiting a scroll-like pattern; it parallels the basal disc of a hanging bowl from Winchester, and may too have been originally placed at the bottom of the Benty Grange bowl.

What remains of one escutcheon belongs to Museums Sheffield and as of 2021 was displayed at Weston Park Museum. The other is held by the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford; as of 2021 it is not on display.

Hanging bowls

Hanging bowls are thin-walled bronze vessels, with three or four equidistant hooks around the rim for suspension, that are associated with Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Viking archaeology and art.[1] The hooks project from escutcheons: bronze plates or frames that are usually circular or oval, and that are frequently elaborately decorated.[1] Basal escutcheons, also known as basal discs, would sometimes sit at the base of the interior.[2] A 2005 catalogue of hanging bowls identified some 174 known examples, around 60 of which were relatively complete.[3] 141 were from Britain and Ireland, 26 from Norway, and 7 from elsewhere in Europe.[4]

The original purpose of hanging bowls, and their place of manufacture, is unknown.[1] They appear to be of Celtic manufacture, with examples still used during Anglo-Saxon and Viking times.[5] Many suggestions have been made as to their original use, including as lamps or lamp reflectors, votive offerings hung in churches, vessels for liturgical use such as washing hands or communion vessels, sanctuary lamps, wayside drinking vessels of the sort Edwin of Northumbria is said to have provided travellers,[6] finger bowls, vessels for weighing wood, magnetic compasses, food containers, holy water stoups, wash basins, and ceremonial vessels used in mead halls.[7] Whatever their original functional purpose, by the seventh century hanging bowls appear to have been increasingly associated with wealth and the status of their owners; by the end of the century, their role as a status symbol may have been more important than any functional purpose.[8]

Description

Two escutcheons are all that remain of the Benty Grange hanging bowl.[9] They are made of enamelled bronze and are 40 mm (1.6 in) in diameter.[9] They have the same design and plain frames, parts of which survive.[9] Both escutcheons are fragmentary; enough survives of each for the design to be reconstructed,[9] and, because of overlapping segments, for it to be certain that they represent two distinct pieces.[10] Whether they are hook or basal escutcheons is uncertain, but a ring on the back of one fragment suggests an association with the suspension chains, and a contemporary watercolour by Llewellynn Jewitt seems to show that a hook may have been present at excavation.[9] The decomposed enamel background appears yellow to the eye,[11] as it did when excavated.[12][13][14] A yellow-creatures-on-red-background colour scheme has also been suggested,[15][16] but on minimal and possibly incorrect evidence.[11] As sampling of the enamel was not permitted when the Sheffield escutcheon was analysed at the museum in 1968, however, the all-yellow hypothesis is not definitive.[17][note 1]

The reconstructed design shows three "ribbon-style fish or dolphin-like creatures", each biting the tail of the animal ahead of it.[9] The bodies are defined by their outlines.[10] They are limbless, the tails curled in a circle, and the jaws both long and curved; where the tails should pass through the jaws of the animals behind, gaps appear, creating slight separations between segments of tail.[9] Each animal has a small eye shaped like a pointed oval.[9] The outer borders of the discs, the plain frames, and the contours and eyes of the animals, are all tinned or silvered.[9]

Surviving records of the third escutcheon indicate that it was of a different style and size.[9][10] Drawings by Bateman and Jewitt show it with a scroll pattern and small piece of frame.[10][12][21] It appears to have been about half the size of the other two, and may have originally been placed at the bottom of the hanging bowl.[9]

The escutcheons were undoubtedly part of an entire hanging bowl when buried.[9] Nothing else survives.[9] The mass of corroded chainwork discovered six feet away, which survives only in illustrations by Jewitt and descriptions by Bateman,[22][23] is unlikely to be related; although a large and intricate chain was found with a cauldron from Sutton Hoo, the Benty Grange chains appear dissimilar.[24] The Benty Grange chainwork was also likely too heavy to have been used to suspend the hanging bowl.[24]

Parallels

The animal designs on the Benty Grange hanging bowl are parallelled by designs on other escutcheons, and even more closely by designs on medieval illuminated manuscripts.[15][25] Three escutcheons from a hanging bowl found in Faversham show animals that also look like dolphins,[26][27][28] but with more developed bodies;[25] a better parallel is with a disc found near the Lullingstone hanging bowl that is also decorated with dolphin-like creatures.[29][30] The third escutcheon from Benty Grange, meanwhile, surviving only in illustration, is most closely parallelled by the basal disc of the Winchester hanging bowl.[31][32]

Despite the similarities with other escutcheon and disc designs, several manuscript illustrations are more closely related to the Benty Grange designs.[25] Bateman remarked on this as early as 1861, "shrewdly" as it turned out,[33] noting that similar patterns were used in "several manuscripts of the VIIth Century, for the purpose of decorating the initial letters".[14] Anglo-Saxon metalwork designs like those on the Benty Grange escutcheons may have inspired aspects of the manuscript art.[34][35] In particular, the mid-seventh-century Durham Gospel Fragment contains two similar fish-like motifs contained within the lateral stroke of the INI monogram that introduces the Gospel of Mark.[10][36] The Book of Durrow also contains a similar illustration of linked yellow dolphin-like creatures.[34][35]

Date

The Benty Grange hanging bowl is typically dated to the second half of the seventh century, based on its design, and the associated finds from the barrow.[31] Given the presence of a helmet and cup with silver crosses, wrote Audrey Ozanne, "[t]he straightforward interpretation of this find would seem to be that it dates from a period subsequent to the official introduction of Christianity into Mercia in 655".[37][38][39] The surviving escutcheons, too, suggest a date in the mid-seventh century, given their resemblance to the illustrations in the Durham Gospel Fragment and the Book of Durrow,[40][41] while the Winchester hanging bowl's basal disc, which the third Benty Grange escutcheon resembles, has traditionally been given the same date.[42]

Discovery

Location

The hanging bowl was discovered in a barrow on the Benty Grange farm in Derbyshire,[43] in what is now the Peak District National Park.[44] Thomas Bateman, an archaeologist and antiquarian who led the excavation,[note 2] described Benty Grange as "a high and bleak situation";[43] its barrow, which still survives, is prominently located by a major Roman road,[47] now the A515, possibly to display the burial to passing travellers.[48] It may have also been designed to share the skyline with two other nearby monuments, Arbor Low stone circle and Gib Hill barrow.[48]

The seventh-century Peak District was a small buffer state between Mercia and Northumbria, occupied, according to the Tribal Hidage, by the Anglo-Saxon Pecsæte.[49][50] The area came under the fold of the Mercian kingdom around the eighth century;[50] the Benty Grange and other rich barrows suggest that the Pecsæte may have had their own dynasty beforehand, but there is no written evidence for this.[49]

Excavation

Bateman excavated the barrow on 3 May 1848.[43] Although he did not mention it in his account, he was likely not the first person to dig up the grave.[51] The fact that the objects were found in two clusters separated by 6 ft (1.8 m), and that other objects that normally accompany a helmet were absent, such as a sword and shield,[52] suggests that the grave had previously been looted.[51] Being so large it may alternatively or additionally have contained two burials, only one of which was discovered by Bateman.[53][note 3]

The barrow comprises a circular central mound approximately 15 m (50 ft) in diameter and 0.6 m (2 ft) high, an encircling fosse about 1 m (3.3 ft) wide and 0.3 m (1 ft) deep, and outer penannular earthworks around 3 m (10 ft) wide and 0.2 m (0.66 ft) high.[53] The entire structure measures approximately 23 by 22 m (75 by 72 ft).[53] Bateman suggested a body once lay at its centre, flat against the original surface of the soil;[43][55] what he described as the one remnant, strands of hair, is now thought to be from a cloak of fur, cowhide or something similar.[56] The recovered objects were found in two clusters.[51][57][58] One cluster was found in the area of the supposed hair, the other about 6 ft (1.8 m) to the west.[57][58] In the latter area Bateman described "a large mass of oxydized iron" which, when removed and washed, presented itself as a jumbled collection of chainwork, a six-pronged piece of iron resembling a hayfork, and the Benty Grange helmet.[59][60][61]

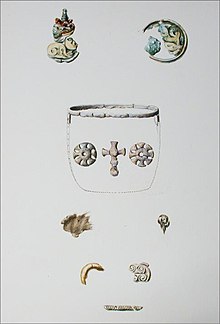

In the area of the supposed hair, Bateman described "a curious assemblage of ornaments", which were difficult to remove successfully from the hardened earth.[43][57] This included a cup identified as leather but probably of wood,[62][63] approximately 3 in (7.6 cm) in diameter at the mouth.[43][12] Its rim was edged with silver,[43] while its surface was "decorated by four wheel-shaped ornaments and two crosses of thin silver, affixed by pins of the same metal, clenched inside".[14] Also found were "a knot of very fine wire", some "thin bone variously ornamented with lozenges &c." attached to silk, but that soon decayed when exposed to air, and the Benty Grange hanging bowl.[12][21][33] As Bateman described it

The other articles found in the same situation are principally personal ornaments, of the same scroll pattern as those figured at page 25 of the Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire;[64]—of these enamels, there were two upon copper, with silver frames; and another of some composition which fell to dust almost immediately: the prevailing colour in all is yellow.[12]

Bateman closed his 1848 account of the excavation by noting the "particularly corrosive nature of the soil",[65] which by 1861 he said "has generally been the case in tumuli in Derbyshire".[66] He suggested that this was the result of "a mixing or tempering with some corrosive liquid; the result of which is the presence of thin ochrey veins in the earth, and the decomposition of nearly the whole of the human remains."[66] Bateman's friend Llewellynn Jewitt, an artist and antiquarian who frequently accompanied Bateman on excavations,[67] painted four watercolours of the finds, parts of which were included in Bateman's 1848 account.[68][note 4] This was more than Jewitt produced for any other of their excavations, a mark of the importance that they assigned to the Benty Grange barrow.[68]

The hanging bowl escutcheons entered the extensive collection of Bateman. On 27 October 1848 he related his discoveries, including the helmet, cup, and hanging bowl, to the British Archæological Association,[70][71][72] and in 1855 they were catalogued along with other objects from the Benty Grange barrow.[73] In 1861 Bateman died at 39,[46] and in 1876 his son, Thomas W. Bateman, loaned the collection to Sheffield.[74] It was displayed at the Weston Park Museum through 1893, at which point the younger Bateman, having seen to his father's fortune, was forced to sell by order of chancery.[75][76] The city purchased many of the objects that had been excavated in Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Staffordshire, including the helmet, the cup fittings, and one of the hanging bowl escutcheons; other pieces were dispersed by Sotheby's,[76][77] and later in 1893 the second escutcheon was presented to the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford by Sir John Evans.[78] As of 2021, the escutcheons remain in the collections of the two museums.[79][78]

The Benty Grange barrow was designated a scheduled monument on 23 October 1970.[53] The list entry notes that "[a]lthough the centre of Benty Grange [barrow] has been partially disturbed by excavation, the monument is otherwise undisturbed and retains significant archaeological remains."[53] It goes on to note that further excavation would yield new information.[53] The nearby farm was renovated between 2012 and 2014;[80][81] as of 2021 it is rented out as a holiday cottage.[82]

Publication

Bateman published an article on the Benty Grange excavation in October 1848—five months after excavating the barrow—in The Journal of the British Archaeological Association.[83] The finds were included in his 1855 catalogue of his collection,[84] and shortly before his death, Bateman revised and expanded upon his 1848 account in his 1861 book Ten Years' Digging in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills.[85] Similarly, Llewellynn Jewitt commented upon the finds, including the hanging bowl, in his 1870 book Grave-mounds and their Contents.[86]

The hanging bowl was one of the first to be discovered, and in 1898 John Romilly Allen included it among 16 examples in the first English article to discuss hanging bowls as a distinct class of artefact.[87][88] It was frequently mentioned in the literature thereafter,[25] including reconstructions by T. D. Kendrick in 1932 and 1938,[89][90] Françoise Henry in 1936,[91] Audrey Ozanne in 1962–1963,[92] George Speake in 1980,[93] and Jane Brenan in 1991.[94] Rupert Bruce-Mitford revisited the Benty Grange burial in 1974,[95] and published what he termed a "definitive" reconstruction of the escutcheons in 1987;[96] in his posthumous 2005 work A Corpus of Late Celtic Hanging-Bowls he added a full description of the hanging bowl, and a colour reconstruction of the escutcheons.[97]

Notes

- ^ Very few hanging bowl escutcheons have yellow rather than red enamel.[18][19] Many that appear yellow in fact contain deteriorated red enamel; such enamel tends to be chalky or powdery instead of glassy, however, and visibly red enamel may remain underneath.[18][20] Although Rupert Bruce-Mitford was unable to sample the enamel when he analyzed the Sheffield escutcheon, he wrote that "[n]o slightest trace of red can be detected in the depths or fractures of the background or the body-filling so far as these are visible".[17] Noting the bodies "are certainly yellow", he termed the all-yellow colour scheme "a working hypothesis".[17] Otherwise, they would likely be yellow-on-red.[17]

- ^ Bateman excavated more than 500 barrows in his lifetime, earning him the moniker "The Barrow Knight."[45][46]

- ^ Llewellynn Jewitt suggested there were two burials in 1870, writing that "In this mound, although a curious and unique helmet, the silver mountings of a leather drinking-cup, some highly interesting and beautiful enamelled ornaments, and other objects, as well as indications of the garments, remained, not a vestige of the body, with the exception of some of the hair, was to be seen. The lovely and delicate form of the female and the form of the stalwart warrior or noble had alike returned to their parent earth, leaving no trace behind, save the enamel of her teeth and traces of his hair alone, while the ornaments they wore and took pride in, and the surroundings of their stations, remained to tell their tale at this distant date."[54]

- ^ The four watercolours are now in the collection of the Weston Park Museum.[68][22][23][69]

References

- ^ a b c Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 3.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, p. 193.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Brenan 1991, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 250 n.5.

- ^ a b Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 77, 119.

- ^ a b c d e Bateman 1848b, p. 277.

- ^ Bateman 1855, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Bateman 1861, p. 29.

- ^ a b Henry 1936, p. 236.

- ^ Haseloff 1990, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 77.

- ^ a b Brown 1981, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 76.

- ^ a b Bateman 1861, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Museums Sheffield chainwork 1.

- ^ a b Museums Sheffield chainwork 2.

- ^ a b Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 250 n.6.

- ^ a b c d Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 120.

- ^ British Museum Faversham 1.

- ^ British Museum Faversham 2.

- ^ British Museum Faversham 3.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 72, 120, 175, 428.

- ^ Vierck 1970, p. 45.

- ^ a b Ozanne 1962–1963, p. 22.

- ^ Winchester hanging bowl.

- ^ a b Bruce-Mitford 1974, pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b Kendrick 1938, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Haseloff 1958, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1987, p. 37.

- ^ Ozanne 1962–1963, p. 20.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 242.

- ^ Longley 1975, p. 25.

- ^ Henry 1936, pp. 218, 236.

- ^ Brenan 1991, pp. 68, 72.

- ^ Ozanne 1962–1963, pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bateman 1861, p. 28.

- ^ Lester 1987, p. 34.

- ^ Goss 1889, p. 176.

- ^ a b Howarth 1899, p. v.

- ^ Ozanne 1962–1963, p. 35.

- ^ a b Brown 2017, p. 21.

- ^ a b Yorke 1990, pp. 9–12, 102, 106, 108.

- ^ a b Keynes 2014, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Bruce-Mitford 1974, p. 229.

- ^ Smith 1908, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f Historic England Benty Grange.

- ^ Jewitt 1870, p. 211.

- ^ Bateman 1848b, p. 276.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1974, pp. 223, pl. 73.

- ^ a b c Bateman 1848b, pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b Bateman 1861, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Bateman 1848b, pp. 277–278.

- ^ Bateman 1861, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1974, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Allen 1898, pp. 46–47, 47 n.a.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1974, pp. 223, 223 n.4.

- ^ Bateman 1848, p. 25.

- ^ Bateman 1848b, p. 279.

- ^ a b Bateman 1861, p. 32.

- ^ Goss 1889, pp. 170–171, 175–176, 249, 301.

- ^ a b c Museums Sheffield escutcheon watercolour.

- ^ Museums Sheffield helmet watercolour.

- ^ The Times 1848.

- ^ The Morning Post 1848.

- ^ The Ipswich Journal 1848.

- ^ Bateman 1855, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Howarth 1899, p. iii.

- ^ Rushforth 2004, pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b Howarth 1899, pp. iii–iv, 244.

- ^ Rushforth 2004, p. 115.

- ^ a b Ashmolean Museum.

- ^ Museums Sheffield escutcheon.

- ^ Peak District Applications 2012.

- ^ BentyGrange Twitter 2014.

- ^ Peak Venues Benty Grange.

- ^ Bateman 1848.

- ^ Bateman 1855.

- ^ Bateman 1861.

- ^ Jewitt 1870, pp. 211, 248–257, 260–261.

- ^ Allen 1898, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, p. 8.

- ^ Kendrick 1932, p. 178.

- ^ Kendrick 1938, p. 100.

- ^ Henry 1936, p. 235.

- ^ Ozanne 1962–1963, p. 21.

- ^ Speake 1980, fig. 11c.

- ^ Brenan 1991, p. 188.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1974.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 1987, pp. 35, 37.

- ^ Bruce-Mitford 2005, pp. 119–120, pl. 3b.

Bibliography

- Allen, John Romilly (1898). "Metal Bowls of the Late-Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Periods". Archaeologia. LVI: 39–56. doi:10.1017/s0261340900003842.

- "Anglo-Saxon Antiquities". The Times. No. 20, 007. London. 30 October 1848. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Anglo-Saxon Antiquities". The Morning Post. No. 23, 370. London. 1 November 1848. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Anglo-Saxon Antiquities". The Morning Post. No. 5, 713. Ipswich. 4 November 1848. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Anglo-Saxon bronze hanging bowl". Hampshire Cultural Trust. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- Bateman, Thomas (1848). Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire and the Sepulchral Usages of its Inhabitants, from the Most Remote Ages to the Reformation. London: John Russell Smith.

- Bateman, Thomas (October 1848b). "Description of the Contents of a Saxon Barrow". The Journal of the British Archaeological Association. IV (3): 276–279. doi:10.1080/00681288.1848.11886866.

- Bateman, Thomas (1855). A Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities and Miscellaneous Objects Preserved in the Museum of Thomas Bateman, at Lomberdale House, Derbyshire. Bakewell: James Gratton.

- Bateman, Thomas (1861). Ten Years' Digging in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills, in the counties of Derby, Stafford, and York, from 1848 to 1858; with notices of some former discoveries, hitherto unpublished, and remarks on the crania and pottery from the mounds. London: John Russell Smith. pp. 28–33.

- Benty Grange [@BentyGrange] (22 August 2014). "We are proud to open the doors to Benty Grange to our first guests. We couldn't have done it without @PeakVenues . THANKS" (Tweet). Retrieved 10 February 2018 – via Twitter.

- "Benty Grange – Barn Conversion – Peak Venues". Peak Venues. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Brenan, Jane (1991). Hanging Bowls and their Contexts: An archaeological survey of their socio-economic significance from the fifth to seventh centuries A.D. British Archaeological Reports. Vol. 220. Tempus Reparatum. ISBN 0-86054-724-8.

- Brown, Antony (October 2017). "Dowlow Quarry ROMP Environmental Statement Appendix 10.2: Setting Assessment" (PDF). ARS Ltd Reports. 2017 (82). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2018.

- Brown, David (1981). "Swastika Patterns". In Evison, Vera Ivy (ed.). Angles, Saxons, and Jutes: Essays Presented to J. N. L. Myres. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 227–240. ISBN 978-0-19-813402-2.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 978-0-575-01704-7.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1987). "Ireland and the Hanging Bowls—A Review". In Ryan, Michael (ed.). Ireland and Insular Art, A.D. 500–1200: Proceedings of a Conference at University College Cork, 31 October-3 November 1985. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. pp. 30–39. ISBN 978-0-901714-54-1.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (2005). Taylor, Robin J. (ed.). A Corpus of Late Celtic Hanging-Bowls with An Account of the Bowls Found in Scandinavia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813410-7.

- Colgrave, Bertram & Mynors, R. A. B., eds. (1969). Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford Medieval Tests. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- "Escutcheon of hanging bowl". Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology. University of Oxford. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Fowler, Elizabeth (1968). "Hanging Bowls". In Coles, John Morton & Simpson, Derek Douglas Alexander (eds.). Studies in Ancient Europe: Essays Presented to Stuart Piggott. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 287–310.

- "Fragments of enamelled escutcheon from Benty Grange". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- Goss, William Henry (1889). The Life and Death of Llewellynn Jewitt, F.S.A., Etc., with Fragmentary Memoirs of Some of his Famous Literary and Artistic Friends, Especially of Samuel Carter Hall, F.S.A., Etc. London: Henry Gray.

- "hanging bowl (.1248.'70)". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- "hanging bowl (.1248.a.'70)". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- "hanging bowl (.1248.b.'70)". The British Museum Collection Online. The British Museum. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Haseloff, Günther (1958). "Fragments of a Hanging-Bowl from Bekesbourne, Kent, and Some Ornamental Problems" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 2. Translated by de Paor, Liam: 72–103. doi:10.1080/00766097.1958.11735474.

- Haseloff, Günther (1990). Email im frühen Mittelalter: Frühchristiliche Kunst von der Spätantike bis zu den Karolingern (in German). Marburg: Hitzeroth. ISBN 978-3-89398-020-8.

- Henry, Françoise (31 December 1936). "Hanging Bowls". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 7th series. VI (II): 209–246. JSTOR 25513828.

- Henry's original drawing available at "Sketch of Benty Grange escutcheon". UCD Digital Library. University College Dublin. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Henry's original drawing available at "Sketch of Benty Grange escutcheon". UCD Digital Library. University College Dublin. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Historic England. "Benty Grange hlaew, Monyash (1013767)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Howarth, Elijah (1899). Catalogue of the Bateman Collection of Antiquities in the Sheffield Public Museum. London: Dulau and Co.

- Jewitt, Llewellynn (1870). Grave-mounds and their Contents: A Manual of Archæology, as Exemplified in the Burials of the Celtic, the Romano-British, and the Anglo-Saxon Periods. London: Groombridge and Sons.

- Kendrick, T. D. (June 1932). "British Hanging Bowls". Antiquity. VI (22): 161–184. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00006700.

- Kendrick, T. D. (1938). Anglo-Saxon Art to A.D. 900. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd.

- Keynes, Simon (2014). "Mercia". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon & Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 311–313. doi:10.1002/9781118316061.ch13. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Lester, Geoff (Fall 1987). "The Anglo-Saxon Helmet from Benty Grange, Derbyshire" (PDF). Old English Newsletter. 21 (1): 34–35. ISSN 0030-1973.

- Longley, David (1975). Hanging-Bowls, Penannular Brooches and the Anglo-Saxon Connexion. British Archaeological Reports. Vol. 22.

- Ozanne, Audrey (1962–1963). "The Peak Dwellers" (PDF). Medieval Archaeology. 6–7: 15–52. doi:10.1080/00766097.1962.11735659.

- Rushforth, Rebecca (2004). "The Barrow Knight, the Bristol Bibliographer, and a Lost Old English Prayer". Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society. XIII (1): 112–131. JSTOR 41154940.

- Smith, Reginald Allender (1908). "Notes on Bronze Hanging-Bowls and Enamelled Mounts". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd series. XXII: 63–86.

- Speake, George (1980). Anglo-Saxon Animal Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813194-6.

- Vierck, Hayo (December 1970). "Cortina Tripodis. Zu Aufhängung und Gebrauch subrömischer Hängebecken aus Britannien und Irland". Frühmittelalterliche Studien (in German). 4: 8–52. doi:10.1515/9783110242041.8. S2CID 188786864.

- "Watercolour of finds from Benty Grange including escutcheon and cup fittings". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Watercolour Showing Fragments of Metal Chainwork". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Watercolour Showing Fragments of Metal Chainwork". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Watercolour showing the helmet from Benty Grange". I Dig Sheffield. Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Weekly List of Applications Validated by the Authority: Applications validated between 18/072012 – 24/07/2012" (PDF). Peak District National Park Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England (PDF). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-44730-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2020.