Dakota people

Charles Alex Eastman (1858–1939), physician, author, and co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,460 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Dakota,[1] English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), traditional tribal religion, Native American Church, Wocekiye | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lakota, Assiniboine, Stoney (Nakota), and other Sioux |

The Dakota (pronounced [daˈkˣota], Dakota language: Dakȟóta/Dakhóta) are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Western Dakota.

The four bands of Eastern Dakota are the Bdewákaŋthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute, and Sisíthuŋwaŋ and are sometimes referred to as the Santee (Isáŋyathi or Isáŋ-athi; "knife" + "encampment", "dwells at the place of knife flint"), who reside in the eastern Dakotas, central Minnesota and northern Iowa. They have federally recognized tribes established in several places.

The Western Dakota are the Yankton, and the Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), who reside in the Upper Missouri River area. The Yankton-Yanktonai are collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena ("Those Who Speak Like Men"). They also have distinct federally recognized tribes. In the past the Western Dakota have been erroneously classified as Nakota, a branch of the Sioux who moved further west. The latter are now located in Montana and across the border in Canada, where they are known as Stoney.[2]

Name

The word Dakota means "ally" in the Dakota language, and their autonyms include Ikčé Wičhášta ("Indian people") and Dakhóta Oyáte ("Dakota people").[3]

Ethnic groups

The Eastern and Western Dakota are two of the three groupings belonging to the Sioux nation (also called Dakota in a broad sense), the third being the Lakota (Thítȟuŋwaŋ or Teton). The three groupings speak dialects that are still relatively mutually intelligible. This is referred to as a common language, Dakota-Lakota, or Sioux.[4]

The Dakota include the following bands:

- Santee division (Eastern Dakota) (Isáŋyathi, meaning "knife camp"[3])

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])

- notable persons: Taoyateduta

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, translating to "swamp/lake/fish scale village"[3])

- Wahpekute (Waȟpékhute, "Leaf Archers")

- notable persons: Inkpaduta

- Wahpeton (Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, "Leaf Village")

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])

- Yankton-Yanktonai division (Western Dakota) (Wičhíyena)

- Yankton (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ, "End Village")

- Yanktonai (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, "Little End Village")

- Upper Yanktonai

- Húŋkpathina or Lower Yanktonai[5]

Language

The Dakota language is a Mississippi Valley Siouan language, belonging to the greater Siouan-Catawban language family. It is closely related to and mutually intelligible with the Lakota language, and both are also more distantly related to the Stoney and Assiniboine languages. Dakota is written in the Latin script and has a dictionary and grammar.[1]

- Eastern Dakota (also known as Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

- Western Dakota (or Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta)

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Upper Yanktonai (Wičhíyena)

History

Before the 17th century, the Santee Dakota (Isáŋyathi; "Knife" also known as the Eastern Dakota) lived around Lake Superior with territories in present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. They gathered wild rice, hunted woodland animals and used canoes to fish. Wars with the Ojibwe throughout the 1700s pushed the Dakota into southern Minnesota, where the Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and Teton (Lakota) were residing. In the 1800s, the Dakota signed treaties with the United States, ceding much of their land in Minnesota. Failure of the United States to make treaty payments on time, as well as low food supplies, led to the Dakota War of 1862, which resulted in the Dakota being exiled from Minnesota to numerous reservations in Nebraska, North and South Dakota and Canada. After 1870, the Dakota people began to return to Minnesota, creating the present-day reservations in the state.

The Yankton and Yanktonai Dakota (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena, resided in the Minnesota River area before ceding their land and moving to South Dakota in 1858. Despite ceding their lands, their treaty with the U.S. government allowed them to maintain their traditional role in the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ as the caretakers of the Pipestone Quarry, which is the cultural center of the Sioux people. They are considered to be the Western Dakota (also called middle Sioux), and have in the past been erroneously classified as Nakota.[6] The actual Nakota are the Assiniboine and Stoney of Western Canada and Montana.

Santee (Isáŋyathi or Eastern Dakota)

Migrations of Ojibwe people from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, who were armed with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Dakota further into Minnesota and west and southward. The US gave the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi River and up to its headwaters.[7]

After the Dakota War of 1862, the federal government expelled the Santee (who included the Mdewakanton) from Minnesota. Many were sent to Crow Creek Indian Reservation east of the Missouri River in what is now South Dakota. In 1864 some from the Crow Creek Reservation were sent to St. Louis and then traveled by boat up the Missouri River, ultimately to the Santee Sioux Reservation.

In the 21st century, the majority of the Santee live on reservations and reserves, and many in small and larger cities in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Canada. They went to cities for more work opportunities and improved living conditions.

Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yankton-Yanktonai or Western Dakota)

The Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, also known by the anglicized spelling Yankton (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ: "End village") and Yanktonai (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna: "Little end village") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the Lower Yanktonai (Húŋkpathina).[7]

They were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, they were recorded as living in the Mankato (Maka To – Earth Blue/Blue Earth) region of southwestern Minnesota along the Blue Earth River.[8]

Most of the Yankton live on the Yankton Indian Reservation in southeastern South Dakota. Some Yankton live on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation and Crow Creek Reservation, which is also occupied by the Lower Yanktonai. The Upper Yanktonai live in the northern part of Standing Rock Reservation, and on the Spirit Lake Reservation, in areas within central North Dakota. Others live in the eastern half of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana. In addition, they reside at several Canadian reserves, including Birdtail, Oak Lake, and Whitecap (formerly Moose Woods).

Modern geographic divisions

The Dakota maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North America: in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Montana in the United States; and in Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Dakota identified them in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. After the introduction of the horse in the early 18th century, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land—from present day Central Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Powder River country.[9]

Modern reservations, reserves, and communities of the Sioux

(* Reserves shared with other First Nations)

Notable Dakota people

Historical

- Hazaiyankawin (Azayamankawin), Mdewakanton Dakota woman who ran canoe ferry service in Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Inkpaduta (Scarlet Point/Red End), Wahpekute Dakota war chief

- Ištáȟba (Sleepy Eye), Sisseton Dakota chief

- Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa (Cloud Man), Mdewakanton Dakota chief

- Ohíyes'a (Charles Eastman), Dakota author, physician and reformer who helped found the Boy Scouts of America

- Snana (Maggie Brass), Mdewakanton woman who saved Mary Schwandt during the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862

- Tamaha (One Eye/Standing Moose), Mdewekanton Dakota scout for the U.S. during the War of 1812

- Thaóyate Dúta (Little Crow III/His Red Nation), Mdewakanton Dakota chief of Kaposia band and military leader during U.S.–Dakota War of 1862

- Ti'wakan (Gabriel Renville), Sisseton Wahpeton chief from 1866 to 1892

- Wapahaśa (Wabasha II), head chief of Mdewakanton Dakota and Kiyuksa band in early 1800s

- Wapahaśa (Wabasha III), head chief of the Santee Sioux

- Wánataŋ (Wanata), Yanktonai Dakota chief

- Wánataŋ (Wanata#Chief Wanataan II), Sisseton Dakota chief, son of the former

- Waŋbdí Okíčhize (War Eagle), Yankton Dakota chief of Santee origin

- Waŋbdí Tháŋka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton Dakota sub-chief

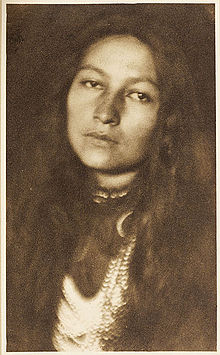

- Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, 1876–1938), Yankton author, educator, musician and political activist

Contemporary

- Ella Cara Deloria (1889 – 1971), author, ethnographer, linguist

- Vine Deloria Jr. (1933–2005), Standing Rock author, activist, historian and theologian

- Floyd Red Crow Westerman/Kanghi Duta (1936–2007), Sisseton Wahpeton actor

- John Trudell (1946–2015), Santee activist, American Indian Movement leader

Contemporary Sioux people are also listed under the tribes to which they belong:

By individual tribe

- Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe of the Crow Creek Reservation

- Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe of the Lower Brule Reservation

- Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community

- Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota

- Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

See also

Citations

- ^ a b c "Dakota." Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ For a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming the Yankton and the Yanktonai as "Nakota", see the article Nakota

- ^ a b c d Barry M. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000; pg. 316

- ^ Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L., "The Siouan languages"; in DeMallie, R.J. (ed) (2001). Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114) [W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.)]. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution: pp. 97 ff; ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- ^ not to be confused with the Oglala thiyóšpaye bearing the same name, "Húŋkpathila"

- ^ for a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming as "Nakota", the Yankton and the Yanktonai, see the article Nakota

- ^ a b Riggs, Stephen R. (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Washington Government Printing Office, Ross & Haines, Inc. ISBN 0-87018-052-5.

- ^ OneRoad, Amos E.; Skinner, Alanson (2003). Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-453-X.

- ^ Mails, Thomas E. (1973). Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-13-217216-X.

- ^ Johnson, Michael (2000). The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Osprey Publishing Oxford. ISBN 1-85532-878-X.

Further reading

- Catherine J. Denial, Making Marriage: Husbands, Wives, and the American State in Dakota and Ojibwe Country. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

- Cynthia Leanne Landrum, The Dakota Sioux Experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

- Waziyatawin, What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland. St. Paul, MN: Living Justice Press, 2008.

External links

- About Dakota Wicohan

- . . 1914.