Electoral Franchise Act

| Electoral Franchise Act | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliament of Canada | |

| |

| Citation | SC 1885 (48 & 49 Vict), c 40; RSC 1886, c 5 |

| Enacted by | Parliament of Canada |

| Enacted | July 14, 1885 |

| Considered by | Senate of Canada |

| Assented to | July 20, 1885 |

| Legislative history | |

| First chamber: Parliament of Canada | |

| Bill title | 103 |

| Introduced by | John A. Macdonald |

| First reading | March 19, 1885 |

| Second reading | April 21, 1885 |

| Third reading | July 4, 1885 |

| Second chamber: Senate of Canada | |

| Bill title | 103 |

| Member(s) in charge | Alexander Campbell |

| First reading | July 7, 1885 |

| Second reading | July 10, 1885 |

| Third reading | July 14, 1885 |

| Repealed by | |

| Franchise Act, 1898 SC 1898 (61 Vict), c 14 | |

| Status: Repealed | |

The Electoral Franchise Act, 1885[1][2] (French: Acte du cens électoral)[3] was a federal statute that regulated elections in Canada for a brief period in the late 19th century. The act was in force from 1885, when it was passed by John A. Macdonald's Conservative majority; to 1898, when Wilfrid Laurier's Liberals repealed it.[4] The Electoral Franchise Act restricted the vote to propertied men over 21. It excluded women, Indigenous people west of Ontario, and those designated "Chinese" or "Mongolian".[5][6]

Background[edit]

Elections legislation had been on the federal agenda since Confederation in 1867. Various bills to regulate the franchise at the federal level were proposed in the House of Commons between 1867 and 1885.[7] Macdonald sought to enact the statute in part because he believed it would be electorally advantageous for the Conservative Party.[8]

The statute came in the wake of other legislative efforts in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom to define more precisely who counted as a citizen or subject. Four years earlier, in 1881, Parliament had enacted the Naturalization and Aliens Act, 1881, which, among other provisions, explicitly provided that Indigenous people did not count as full British subjects unless they were able to vote.[9]

Debates and drafting[edit]

The House of Commons debated Bill 103—which would become the Electoral Franchise Act—between March and June 1885.[5] The text initially would have allowed "spinsters" and widows who met property qualifications, as well as all Indigenous people who owned land with at least $150 in capital investment, to vote.[5] Macdonald spoke in favour of women's suffrage at several points during the debates.[10]

Early versions of the Electoral Franchise Act extended the franchise to all Indigenous peoples living in Canada, but following the North-West Rebellion, which occurred the same year the act was passed,[8] it restricted voting rights only to those living in eastern Canada.[8]

Indigenous communities including the Six Nations of the Grand River, as well as a number of Conservatives in Parliament, opposed the bill; others, including some members of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, supported it.[8] Some Indigenous communities rejected the Electoral Franchise Act because it followed a line of other statutes, including the Gradual Civilization Act, 1857,[11] and Gradual Enfranchisement Act, 1869,[12] that gave Indigenous people the right to vote in Canadian elections but imposed federal control over their affairs and promoted policies of "assimilation".[13][14] Such legislation also required Indigenous people to live off reserve and renounce their Indian status to be enfranchised.[15] These statutes also mandated that Indigenous people be fluent in English or French, have "good moral character", be educated, and lack debt, if they desired to become citizens.[16] As of 1876, only one Indigenous person had chosen to become a citizen through this process.[17]

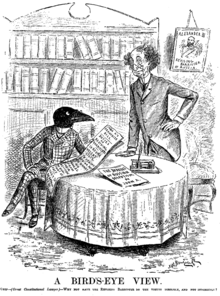

The Liberal Party, which strongly opposed the bill, paid people to find signatures for a petition against it.[18] Liberals argued that the statute would increase patronage and would be expensive to administer.[19] Liberals also argued that the Electoral Franchise Act would perpetuate Macdonald's hold over national political institutions, which he had maintained through initiatives such as the National Policy; and the gerrymander of 1882, which extensively redrew riding lines through the Representation Act, 1882.[20][21] Conservatives countered that the statute would promote "national feeling" by putting control over elections in the national government.[22][23]

The act passed in the House of Commons at 1:00 am on July 4, 1885.[24][25] It received royal assent on July 20.[2]

Provisions[edit]

Jack Little argues that the Electoral Franchise Act was intended to "replace the use of provincial voting lists with uniform nation-wide franchise qualifications for federal elections".[26]

The statute restricted the right to vote to men over 21 who were either born or naturalized British subjects.[27] Amendments from the original text of the bill restricted the franchise considerably, preventing all women,[5] most Indigenous people west of Ontario,[5] and those of "Mongolian or Chinese race"[6][28] from voting. On May 4, 1885, Macdonald himself introduced the amendment restricting anyone identified as a "Chinaman" from voting.[29]

The act also imposed a property qualification on the franchise which varied depending on the elector's residence.[27] John Douglas Belshaw argues that, in practice, "what appear[ed] to be universal male suffrage was in fact only extended to males who satisfied residence requirements".[30] Nonetheless, the statute did increase suffrage among men as compared to earlier legislation.[31]

In a shift from previous federal legislation, the Electoral Franchise Act did not Indigenous people to surrender Indian status in order to vote.[32]

Legacy[edit]

In a letter to Charles Tupper, Macdonald called the statute his "greatest triumph".[33][34][35] Gordon Stewart argues that the legislation was of "basic importance" to Macdonald and his party because electoral margins at the time were routinely razor-thin and thus control over lists of those qualified to vote was vital in winning elections.[36]

Wilfrid Laurier's Liberal majority repealed the Electoral Franchise Act in 1898. The Franchise Act, 1898, received royal assent on June 13, 1898.[37][38]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Electoral Franchise Act, 1885, SC 1885 (48 & 49 Vict), c 40; RSC 1886, c 5.

- ^ a b Hodgins 1886, p. 13.

- ^ "Des progrès inégaux, 1867-1919". Élections Canada. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ Little 2018, pp. 539–540.

- ^ a b c d e Strong-Boag 2013, p. 69.

- ^ a b Preece, Rod (1984). "The Political Wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald". Canadian Journal of Political Science. 17 (3): 485. doi:10.1017/S0008423900031863. ISSN 0008-4239. JSTOR 3227603.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Little 2018, p. 539.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, p. 77.

- ^ Gradual Civilization Act, 1857, SPC 1857 (20 Vict), c 26.

- ^ Gradual Enfranchisement Act, 1869, SC 1869 (32 & 33 Vict), c 6.

- ^ Little 2018, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Mawhiney, Anne-Marie (1994). Towards Aboriginal Self-Government: Relations between Status Indian Peoples and the Government of Canada, 1969–1984. New York: Garland. pp. 23–25. ISBN 0-8153-0823-X. OCLC 1195024254.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Danziger 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Danziger 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Sherwin 2012, p. 94.

- ^ Kennedy, W. P. M (1922). The Constitution of Canada: An Introduction to Its Development and Law. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 387–388. OCLC 697697019.

- ^ Emery 2015, p. 81.

- ^ Dawson, R. MacGregor (May 1935). "The Gerrymander of 1882". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 1 (2): 197–221. doi:10.2307/136689. JSTOR 136689.

- ^ Forster, Davidson & Brown 1986, p. 18.

- ^ An Act to readjust the Representation in the House of Commons, and for other purposes, SC 1882 (45 Vict), c 3.

- ^ Sherwin 2012, p. 97.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, p. 70.

- ^ Little 2018, p. 541.

- ^ a b Elections Canada 2021, p. 71.

- ^ Courtney, John C. (December 18, 2020). "Right to Vote in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ Strong-Boag 2013, p. 88.

- ^ Belshaw 2016, p. 148.

- ^ Forster, Davidson & Brown 1986, p. 19.

- ^ Little 2018, pp. 557–558.

- ^ Kirkby, Coel (2020). "Paradises Lost? The Constitutional Politics of 'Indian' Enfranchisement in Canada, 1857–1900". Osgoode Hall Law Journal. 56 (3): 616. ISSN 0380-1683. 2020 CanLIIDocs 3528.

- ^ Stewart 1982, p. 3.

- ^ Creighton, Donald Grant (1955). John A. Macdonald: The Old Chieftain. Toronto: Macmillan. p. 427. OCLC 1150066016.

- ^ Stewart 1982, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Sherwin 2012, p. 187.

- ^ Franchise Act, 1898, SC 1898 (61 Vict), c 14.

Sources[edit]

- Belshaw, John Douglas (2016). Canadian History: Post-Confederation. Victoria, British Columbia: BCampus. ISBN 978-1-989623-13-8. OCLC 1119464881.

- Danziger, Edmund Jefferson (2009). Great Lakes Indian Accommodation and Resistance during the Early Reservation Years, 1850–1900. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-09690-9. OCLC 270131530.

- A History of the Vote in Canada (3rd ed.). Gatineau, Quebec: Elections Canada. 2021. ISBN 978-0-660-37056-9.

- Emery, George Neil (2015). Principles and Gerrymanders: Parliamentary Redistribution of Ridings in Ontario, 1840–1954. Montreal: McGill–Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9750-1. OCLC 922140922.

- Forster, Ben; Davidson, Malcolm; Brown, R. Craig (March 1986). "The Franchise, Personators, and Dead Men: An Inquiry into the Voters' Lists and the Election of 1891". Canadian Historical Review. 67 (1): 17–41. doi:10.3138/CHR-067-01-02. ISSN 0008-3755. S2CID 153878839.

- Hodgins, Thomas (1886). The Canadian Franchise Act. Toronto: Rowsell & Hutchinson.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Kirkby, Coel (August 2019). "Reconstituting Canada: The Enfranchisement and Disenfranchisement of 'Indians,' circa 1837–1900". University of Toronto Law Journal. 69 (4): 497–539. doi:10.3138/utlj.2018-0078. ISSN 0042-0220.

- Little, Jack I. (October 2018). "Courting the First Nations Vote: Ontario's Grand River Reserve and the Electoral Franchise Act of 1885". Journal of Canadian Studies. 52 (2): 538–569. doi:10.3138/jcs.2017-0071.r1. ISSN 0021-9495. S2CID 149763260. Project MUSE 708852.

- Sherwin, Allan L. (2012). Bridging Two Peoples: Chief Peter E. Jones, 1843–1909. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-652-3. OCLC 806521138.

- Stewart, Gordon (March 1982). "John A. Macdonald's Greatest Triumph". Canadian Historical Review. 63 (1): 3–33. doi:10.3138/CHR-063-01-02. ISSN 0008-3755. S2CID 154847686. Project MUSE 571007.

- Strong-Boag, Veronica (2013). "'The Citizenship Debates': The 1885 Franchise Act". In Adamoski, Robert; Chunn, Dorothy; Menzies, Robert (eds.). Contesting Canadian Citizenship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 69–94. doi:10.3138/9781442602496-004. ISBN 978-1-4426-0249-6. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctvg252bm.6.