Flathead River

| Flathead River | |

|---|---|

The river near Perma, Montana | |

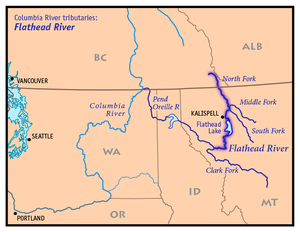

Map of the Flathead River, its tributary forks and downriver connection to the Columbia River via Clark Fork and the Pend Oreille River | |

| Native name |

|

| Location | |

| Country | United States, Canada |

| State | Montana |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Confluence of North Fork and Middle Fork Flathead River |

| • location | Rocky Mountains |

| • coordinates | 48°28′2″N 114°4′10″W / 48.46722°N 114.06944°W[1] |

| • elevation | 3,120 ft (950 m) |

| Mouth | Clark Fork |

• location | Montana |

• coordinates | 47°21′56″N 114°46′34″W / 47.36556°N 114.77611°W[1] |

• elevation | 2,484 ft (757 m)[2] |

| Length | 158 mi (254 km)[3] |

| Basin size | 8,795 sq mi (22,780 km2)[4] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near mouth, at Perma, MT; max at Polson, MT[4] |

| • average | 11,380 cu ft/s (322 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 2,670 cu ft/s (76 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 110,000 cu ft/s (3,100 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Middle Fork Flathead River, South Fork Flathead River, Swan River (Montana) |

| • right | Stillwater River, North Fork Flathead River |

| Type | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated | October 12, 1976 |

The Flathead River (Template:Lang-fla, ntx̣ʷe, Template:Lang-kut),[5] in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Montana, originates in the Canadian Rockies to the north of Glacier National Park and flows southwest into Flathead Lake, then after a journey of 158 miles (254 km), empties into the Clark Fork. The river is part of the Columbia River drainage basin, as the Clark Fork is a tributary of the Pend Oreille River, a Columbia River tributary. With a drainage basin extending over 8,795 square miles (22,780 km2) and an average discharge of 11,380 cubic feet per second (322 m3/s), the Flathead is the largest tributary of the Clark Fork and constitutes over half of its flow.[6]

Course

The Flathead River rises in forks in the Rocky Mountains of northwestern Montana. The largest tributary is the North Fork, which runs from the Canadian province of British Columbia southwards. The North Fork is sometimes considered the main stem of the Flathead River.[7][8] Near West Glacier the North Fork combines with the Middle Fork to form the main Flathead River.[3] The river then flows westwards to join the South Fork and cuts between the Whitefish Range and Swan Range via Bad Rock Canyon. All of the headwaters forks are entirely or in part designated National Wild and Scenic Rivers. After the river leaves the canyon it flows into the broad Flathead Valley and arcs southwest, passing Columbia Falls and Kalispell, before it is joined by the Stillwater River and its Whitefish River tributary, and then empties into Flathead Lake, where the Swan River joins.[3][9]

Near Polson the river leaves the natural basin of Flathead Lake, but first passes through Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ Dam (formerly Kerr Dam), which raises Flathead Lake's level by 10 feet.[10] After flowing through the dam the river turns south and meanders through the Flathead Valley west of the Mission Mountains, and at Dixon it is joined by the small Jocko River. At the Jocko River confluence it turns west, and a few miles after flows into the Clark Fork near Paradise.[11]

History

David Thompson (explorer) first explored the area in 1807. Fur traders employed by the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company entered the Flathead Valley in the early 19th century. Trading posts were established north of Flathead Lake. The 1846 settlement of the Oregon Boundary Dispute established the border with British North America and that the Flathead Valley was firmly American. The first settlers began arriving in the 1860s. Irrigation agriculture began in the 1880s.[12]

The river was affected by the 2022 Montana floods.[13]

Recreation

The river is a Class I river in Montana for purposes of recreational access.[14] The South fork of the Flathead, from Youngs Creek to Hungry Horse reservoir; Middle fork of the Flathead – from Schaffer creek to its confluence with the Flathead River; and the Flathead River – to its confluence with the Clark Fork River, are designated.

Conservation

It is part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Reaches designated wild and scenic include the entire North Fork south of the Canada–US border, the entire Middle Fork, and the South Fork above Hungry Horse Reservoir.[15]

The North Fork Flathead River in Montana is designated a National Wild and Scenic River. The river is not afforded any protection in British Columbia. This has been the subject of 33 years of dispute between the United States and Canada. In 1988 the International Joint Commission, ruled that a proposed open pit coal mine would violate the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty.

Energy development once threatened the North Fork, which was deemed the "wildest river in the continental United States" by The New York Times in 2004. On February 21, 2008, BP announced to drop plans to obtain drilling rights for coalbed methane extraction in the river's headwaters. However, the Cline Mining Corporation still intends to start a mountaintop-removal coal mining project.[16]

On February 9, 2010, the British Columbia government announced that it would not permit mining, oil and gas development and coalbed gas extraction in British Columbia's portion of the Flathead Valley, which was praised by environmental groups and the U.S. Senators from Montana.[17]

There is a proposal to protect one-third of British Columbia's Flathead River by adding it to the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. In 2003 Parks Canada requested the province of British Columbia to take part in a park feasibility study. British Columbia has yet to agree to this.

Further reading

- Sullivan, Gordon (2008). Saving Homewaters–The Story of Montana's Streams and Rivers. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-0-88150-679-2.

See also

- List of rivers of Montana

- Montana Stream Access Law

- Montana Wilderness Association

- Tributaries of the Columbia River

- Flathead Lake

References

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Flathead River

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS coordinates

- ^ a b c Fischer, Carol (1990). Paddling Montana. Globe Pequot. pp. 61, 67–69, 72–74, 78–79. ISBN 978-1-56044-589-0.

- ^ a b c Montana Water Resources Data, 2004, USGS

- ^ Tachini, Pete (2010). Seliš nyoʻnuntn, Medicine for the Salish language : English to Salish translation dictionary (2nd ed.). Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College Press. p. 242. ISBN 9781934594063.

- ^ "USGS 12389000 Clark Fork near Plains MT" (PDF). USGS. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Flathead Subbasin Plan" (PDF). Northwest Power and Conservation Council. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Fischer, Carol (1990). Paddling Montana. Globe Pequot. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-1-56044-589-0.

- ^ "Montana Fishing Guide: Flathead River". Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ Kerr Dam Essay

- ^ Course info mainly from: Montana Atlas & Gazetteer (4th ed.). DeLorme. 2001. ISBN 0-89933-339-7.

- ^ Hungry Horse Project Archived 2007-06-10 at the Wayback Machine, United States Bureau of Reclamation

- ^ "Conditions remain dangerous on Flathead River". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ Stream Access in Montana Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Flathead Wild and Scenic River, Montana". The Wild & Scenic Rivers Council. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Flathead Beacon: BP Drops Coal-Bed Methane Exploration Project North of Glacier Park, February 22, 2008

- ^ Senators praise Canada’s commitment to protect flathead valley : [1] Archived 2010-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, February 9, 2010

External links

- http://www.nwcouncil.org/fw/subbasinplanning/flathead/plan/

- Flathead Wild. Keep it Wild. Keep it Connected.

- Wildsight