Food choice of older adults

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (November 2014) |

Research into food preferences in older adults and seniors considers how people's dietary experiences change with ageing, and helps people understand how taste, nutrition, and food choices can change throughout one's lifetime, particularly when people approach the age of 70 or beyond. Influencing variables can include: social and cultural environment, gender and/or personal habits, and also physical and mental health. Scientific studies have been performed to explain why people like or dislike certain foods and what factors may affect these preferences.

The science of food preferences

[edit]

Research in this area is usually done in order to examine the variables that cause the elderly to change their food preferences; an example is the Elderly Nutrition Program (ENP). The ENP was implemented in 1972 to explore how food preferences varied depending on biological sex and ethnic groups, the goal being to improve the quality of meal programs.

Meals and preferences for 13 food groups, including fresh fruit, chicken, soup, salad, vegetables, potatoes, meat, sandwiches, pasta, canned fruit, legumes, deli meats, and ethnic foods, were assessed in order to gain a general impression of people's dietary habits and food preferences. After adjusting for variables, older male subjects were found to be significantly more likely to prefer deli meats, meat, legumes, canned fruit, and ethnic foods compared to females. In addition, compared with African Americans, the study found that "... Caucasians demonstrated higher percentages of preference for 9 of 13 food groups including pasta, meat, and fresh fruit", and recommended that "... To improve the quality of the ENP, and to increase dietary compliance of the older adults to the programs, the nutritional services require a strategic meal plan that solicits and incorporates older adults' food preferences".[2]

Influences on food preference

[edit]There are multiple factors in an elderly person's life that can affect food preferences. Aspects like their environment, mental and physical health, and lifestyle choices can all contribute to the individual taste and/or habits of elderly people.

An article about Influences on Cognitive Function in Older Adults (Neuropsychology, November 2014) states that "the nutritional status of older adults relates to their quality of life, ability to live independently, and their risk for developing costly chronic illnesses. An aging adult’s nutritional well-being can be affected by multiple socio-environmental factors, including access to healthy and affordable foods, congregate meal sites, and nutritious selections at restaurants. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Society for Nutrition, and the Society for Nutrition Education have identified an older adult's access to a balanced diet to be critical for the prevention of disease and promotion of nutritional wellness so that quality of life and independence can be maintained throughout the aging process and excessive health care costs can be reduced".[3]

Younger vs. older adults

[edit]A person's taste buds, needs for certain vitamins and other nutrients, and their desire for different types of food can change throughout that person's life. 50 young adults and 48 elderly adults participated in a study by the Monell Chemical Senses Center.[4] "Young" subjects ranged from 18 to 35 years of age, and "elderly" subjects were defined as 65 years of age or older. There were more females than males in the study, but there were approximately equal proportions of males and females in the two age groups.

The study observed that younger females had stronger cravings for sweets than elderly females. Possible causes considered for this difference were the younger female test subjects' menstrual cycles and the fact that elderly women may have gone through menopause. The study also postulated that "... Ninety-one percent (91%) of the cycle-associated cravings were said to occur in the second half of the cycle (between ovulation and the start of menstruation)".[4]

These physical changes can be considered when assessing why an older person might not be getting the nutrition they need. As taste buds change with age, certain foods might not be seen as appetizing. For example, a study done by Dr. Phyllis B. Grzegorczyk concluded that as people age, their sense for tasting salty foods slowly goes away.[5]

Male vs. female

[edit]

There are differences in food preferences between the sexes. In a study conducted by the ENP, preferences of male and female subjects were identified in the following 13 individual food groups: fresh fruit, chicken, soup, salad, vegetables, potatoes, meat, sandwiches, pasta, canned fruit, legumes, deli meats, and ethnic groups.

Through this study, it was apparent that older males were "significantly more likely to prefer deli meats, meat, legumes, canned fruit, and ethnic foods compared to females".[2]

Another study by the Monell Chemical Senses Center concluded that females had significantly more cravings for sweets and for chocolate than males; and the study results suggested that males had more cravings or preferences for entrées than sweets.[4]

Personal health

[edit]Physical health

[edit]Some older people avoid certain foods or are unwilling to modify their diets due to oral health problems. These issues, such as ill-fitting dentures (false teeth) or gum disease, are correlated with significant differences in dietary quality, which is a measure of the quality of the diet using a total of eight recommendations regarding the consumption of foods and nutrients from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS). Approaches to minimize food avoidance and promote changes to the diets of people with eating difficulties due to oral health conditions are needed desperately, because without being able to chew or take in food properly, their health is affected dramatically, and their food preferences are limited greatly (too soft or liquids only).[6]

Due to varying factors in older adults' physical and mental well-being, eating choices can become more restricted. Many elderly people are forced into eating softer foods, foods that incorporate fiber and protein, drinking calcium-packed liquids, and so on. Six of the leading causes of death for older adults, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, Alzheimer's disease, and diabetes mellitus, have nutrition-related causes and/or respond favorably to nutrition interventions.[7] These six illnesses can implement certain restrictions and heavily influence the diet of elderly persons.

Declines in physical health, such as conditions like arthritis, can also cause deterioration in diet due to difficulties in preparing and eating food.[8]

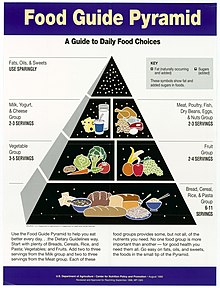

At the 2010 "Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age" conference sponsored by the Institute of Medicine, Dr. Katherine Tucker noted that the elderly are less active and have lower metabolic rates, with a consequent reduced need to eat.[9] In addition, they tend to have existing diseases and/or take medications that interfere with nutrient absorption. Based on their research dietary requirements, one study developed a modified food pyramid for adults over 70.[10]

There is not enough evidence to confidently recommend the use of any form of carbohydrate in preventing or reducing cognitive decline in older adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment.[11] More evidence is needed to evaluate memory improvement and find nutritional issues due to carbohydrates.

Mental health

[edit]The impact of certain diseases can also impact the quality of the food in the elderly population, especially those that are in care facilities. Certain risk factors include conditions that impair cognitive function, such as dementia. When a person falls victim to a condition that limits mental capacity, mortality risk can rise if due care is not implemented.[12]

As a result of certain mental health conditions and/or diseases—like Alzheimer's disease—a person's food preferences might become affected. With certain diseases, individuals can develop specific preferences or distaste for various types of food that were not present before onset. For example, people with Alzheimer's disease may experience many big and small changes as a result of their symptoms.[13] One change identified by Suszynski in "How Dementia Tampers with Taste Buds" is within the taste buds of a patient with dementia, which contain the receptors for taste. Since the experience of flavor is significantly altered, people with dementia can often change their eating habits and take on entirely new food preferences. In this study, the researchers found that these dementia patients had trouble identifying flavors and appeared to have lost the ability to remember tastes, therefore leading to a theory that dementia caused the patients to lose their knowledge of flavors.[13]

Psychological conditions can also affect elderly eating habits. For instance, the length of widowhood may affect nutrition.[14] Depression in elderly people is also associated with a risk of malnutrition.[15]

Lifestyle choices

[edit]Elderly people, like all people, have different lifestyle choices involved in their eating habits. Dietary choices are often a result of personal beliefs and preferences.[8]

A survey based on self-reporting found that many rural elderly Iowans adopted eating habits that provided inadequate levels of some key nutrients, and most did not take supplements to correct the deficiencies.[16] In contrast, a restaurant study found that the impact of a lifestyle of health and sustainability on healthy food choices is much stronger for senior diners than for non-senior diners.[17]

Other research has found that adults, regardless of age, will tend to increase fruit and vegetable consumption following a diagnosis of breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer.[8]

Social environment and conditioning

[edit]The environment can greatly impact the food preferences of older adults. Those around 75 years old and older are more likely to suffer from limited mobility due to health conditions,[18] and often rely on others for food shopping and preparation.[19]

In some areas, homebound seniors receive one meal per day (several fresh and frozen meals may be included in a single delivery) from communities[clarification needed] that offer congregate[clarification needed] meals, or meals served in community settings such as senior centers, churches, or senior housing communities.[20] These congregate meal programs are encouraged[by whom?] to offer these elderly people a meal at least five times per week.

Impeded access to transportation may also be an issue for elderly persons, especially in rural areas where there is less public transportation. This can vary greatly with geographic location; for instance, an Iowa-based study failed to find problems in purchasing food among the elderly in rural open country and towns, as those without their own transportation relied on family, friends, and senior services.[19] A separate study found a slight difference in urban areas with[clarification needed] elderly who did not own a car.[21] Aside from transportation, the kind and quality of available food can also shape food choices if a person lives in a so-called "food desert".

Social network type can also affect individuals' food choices in our elderly population. For example, one study showed that someone with a larger social network and lower economic status is more likely to have proper nutrition than someone who has a smaller social network and higher economic status.[22] Health and social aid can be instrumental in introducing positive change for those at risk.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion (CNPP) | USDA-FNS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Song HJ, Simon JR, Patel DU (March 21, 2014). "Food preferences of older adults in senior nutrition programs". Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 33 (1): 55–67. doi:10.1080/21551197.2013.875502. PMID 24597997. S2CID 39424671.

- ^ Brewster PW, Melrose RJ, Marquine MJ, Johnson JK, Napoles A, MacKay-Brandt A, et al. (November 2014). "Life experience and demographic influences on cognitive function in older adults". Neuropsychology. 28 (6): 846–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.6629. doi:10.1037/neu0000098. PMC 4227962. PMID 24933483.

- ^ a b c Pelchat ML (April 1997). "Food cravings in young and elderly adults". Appetite. 28 (2): 103–13. doi:10.1006/appe.1996.0063. PMID 9158846. S2CID 9126783.

- ^ Grzegorczyk PB, Jones SW, Mistretta CM (November 1979). "Age-related differences in salt taste acuity". Journal of Gerontology. 34 (6): 834–40. doi:10.1093/geronj/34.6.834. PMID 512303.

- ^ Savoca MR, Arcury TA, Leng X, Chen H, Bell RA, Anderson AM, et al. (July 2010). "Association between dietary quality of rural older adults and self-reported food avoidance and food modification due to oral health problems". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (7): 1225–32. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02909.x. PMC 3098620. PMID 20533966.

- ^ Jung SE, Lawrence J, Hermann J, McMahon A (2020). "Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Nutrition Students' Intention to Work with Older Adults". Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 39 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1080/21551197.2019.1664967. PMID 31517572. S2CID 202569535.

- ^ a b c Nicklett EJ, Kadell AR (August 2013). "Fruit and vegetable intake among older adults: a scoping review". Maturitas. 75 (4): 305–12. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.005. PMC 3713183. PMID 23769545.

- ^ Tucker K (2010). "Chapter 5: Diet Quality Issues for Aging Populations". Institute of Medicine (US) Food Forum. Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age: Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-15883-1.

- ^ Russell RM, Rasmussen H, Lichtenstein AH (March 1999). "Modified Food Guide Pyramid for people over seventy years of age". The Journal of Nutrition. 129 (3): 751–3. doi:10.1093/jn/129.3.751. PMID 10082784.

- ^ Ooi CP, Loke SC, Yassin Z, Hamid TA (April 2011). "Carbohydrates for improving the cognitive performance of independent-living older adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (4): CD007220. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007220.pub2. PMC 7388979. PMID 21491398.

- ^ Field K, Duizer LM (2016-08-01). "Food Sensory Properties and the Older Adult". Journal of Texture Studies. 47 (4): 266–276. doi:10.1111/jtxs.12197. ISSN 1745-4603.

- ^ a b Suszynski M. "How Dementia Tampers With Taste Buds". EverydayHealth.com. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ Quandt SA, McDonald J, Arcury TA, Bell RA, Vitolins MZ (February 2000). "Nutritional self-management of elderly widows in rural communities". The Gerontologist. 40 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1093/geront/40.1.86. PMID 10750316.

- ^ Vafaei Z, Mokhtari H, Sadooghi Z, Meamar R, Chitsaz A, Moeini M (March 2013). "Malnutrition is associated with depression in rural elderly population". Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 18 (Suppl 1): S15-9. PMC 3743311. PMID 23961277.

- ^ Marshall TA, Stumbo PJ, Warren JJ, Xie XJ (August 2001). "Inadequate nutrient intakes are common and are associated with low diet variety in rural, community-dwelling elderly". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (8): 2192–6. doi:10.1093/jn/131.8.2192. PMID 11481416.

- ^ Kim MJ, Lee CK, Kim WG, Kim JM (2013). "Relationships Between Lifestyle Of Health And Sustainability And Healthy Food Choices For Seniors". International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 25 (4): 558–576. doi:10.1108/09596111311322925.

- ^ "Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey 2014" (PDF). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. 2014. Retrieved Nov 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Bitto EA, Morton LW, Oakland MJ, Sand M (2003). "Grocery Store Access Patterns in Rural Food Deserts". Journal for the Study of Food and Society. 6 (2): 35–48. doi:10.2752/152897903786769616. S2CID 144158597.

- ^ "Congregate Meals". mhcc.maryland.gov/. Maryland Health Care Commission. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Fitzpatrick K, Greenhalgh-Stanley N, Ver Ploeg M (2016). "The Impact of Food Deserts on Food Insufficiency and SNAP Participation among the Elderly". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 98: 19–40. doi:10.1093/ajae/aav044.

- ^ Kim CO (January 2016). "Food choice patterns among frail older adults: The associations between social network, food choice values, and diet quality". Appetite. 96: 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.015. PMID 26385288. S2CID 29192742.