Hokum

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2010) |

Hokum is a particular song type of American blues music—a humorous song which uses extended analogies or euphemistic terms to make sexual innuendos. This trope goes back to early blues recordings and is used from time to time in modern American blues and blues rock.

An example of hokum lyrics is this sample from "Meat Balls", by Lil Johnson, recorded about 1937:

Got out late last night, in the rain and sleet

Tryin' to find a butcher that grind my meat

Yes I'm lookin' for a butcher

He must be long and tall

If he want to grind my meat

'Cause I'm wild about my meat balls.

Technique

In a general sense, hokum was a style of comedic farce, spoken, sung and spoofed, while masked in both risqué innuendo and "tomfoolery". It is one of the many legacies and techniques of 19th century blackface minstrelsy. Like so many other elements of the minstrel show, stereotypes of racial, ethnic and sexual fools were the stock in trade of hokum. Hokum was stagecraft, gags and routines for embracing farce. It was so broad that there was no mistaking its ludicrousness. Hokum also encompassed dances like the cakewalk and the buzzard lope in skits that unfolded through spoken narrative and song. W. C. Handy, himself a veteran of a minstrel troupe, remarked that, "Our hokum hooked 'em," meaning that the low comedy snared an audience that stuck around to hear the music. In the days before ragtime, jazz and even hillbilly music and the blues were clearly identified as specific genres, hokum was a component of all-around performing, entertainment that seamlessly mixed monologues, dialogues, dances, music, and humor.

Minstrel show origins

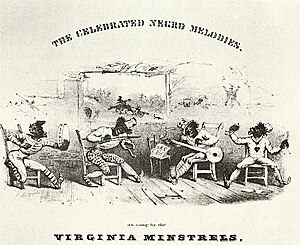

The minstrel show began in Northern cities, primarily in New York's Five Points section, in the 1830s. Minstrelsy was a mixture of Scottish and Irish folk music forms fused with African rhythms and dance. It is difficult to tease out those strands, considering the mixed motives of the showmen who presented the minstrel show and the mixed audience who patronized it. It is said that T. D. Rice invented the buck and wing and the Jim Crow, by imitating the stumbling of an old lame black man, and added numerous steps and shuffles after watching an African American boy improvise a version of an Irish jig in a back alley. Soon, the confusion became so complete that almost any minstrel tune played upon the banjo became known as a jig, regardless of time signatures or lyric accompaniment. Banjo player Joe Ayers told old-time musician and writer Bob Carlin that "the origins of playing Irish jigs on the banjo probably go back to minstrel banjoist Joel Walker Sweeney's appearances in Dublin in 1844." Genuine appreciation among white observers for music and dance so clearly (if not purely) African in origin existed then and now. Charles Dickens praised the intricacies of the "lively hero" (believed to be Master Juba) whom he watched in a New York performance in 1842. Many songs that originated in minstrelsy (such as "Camptown Races" and "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny") are now considered American classics. While it was originally performed by whites costumed in either fanciful "dandy" gear or pauper's rags with their faces covered in burnt cork, or blackface, the minstrels were joined in the 1850s by African-American performers. The dancer William Henry Lane (better known by his stage name Master Juba) and the fiddling dwarf Thomas Dilward were also "corking up" and performing alongside whites in such touring ensembles as the Virginia Minstrels, the Ethiopian Serenaders, and Christy's Minstrels. Minstrel troupes composed entirely of African Americans appeared in the same decade. After the American Civil War, traveling productions like Callender's Georgia Minstrels would rival the white ensembles in fame, while falling short of them in earnings. The difficulties racism presented to African-American entrepreneurs during postwar Reconstruction era made touring a dangerous and precarious livelihood.

Subversion and confrontation

Although mainly Northern in origin, many minstrel shows, black or white, celebrated "Dixieland" and presented a loose concoction of "Negro melodies" and "plantation songs" infused with slapstick, word play, skits, puns, dance, and stock characters. The hierarchies of the social order were satirized, but seldom challenged. While hokum mocked the propriety of "polite" society, the presumptions and pretensions of the parodists were simultaneous targets of the humor. "Darkies" dancing the cakewalk might mimic the elite cotillion dance styles of wealthy Southern whites, but their exaggerated high-stepping exuberance was judged all the funnier for its ineptitude. Nonetheless, styles of song and dance that began as inversions of the social structure were adopted among the upper echelons of society, often without a trace of self-consciousness.

Social insults were more overt. As the underclass being ridiculed shifted, the racist lampoons and blackface burlesques sometimes gave way to other conflations, such as the stage Irishman Paddy, drunken and belligerent, a cruel caricature often in blackface himself. Political nativism and xenophobia encouraged similar mean-spirited responses to perceived threats of the time. After 1848, when the first substantial influx of Chinese immigrants began seeking their fortunes in the California Gold Rush, "Chink" characters joined the minstrel walkaround. Hokum enjoyed the license to be outrageous, since the clowning was purportedly "all in fun".

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the hierarchy of social mores that sanctioned stereotyping came increasingly under attack. W. E. B. Du Bois's book The Souls of Black Folk linked the subjective self-appraisal of African Americans to their struggle with pejorative stereotyping in his essays about "double consciousness". This inner conflict was central to the African-American experience, "this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity". Anticipating social psychology, DuBois had identified a whole sphere of comparative attitudes that allowed for the reinterpretation of the black "mask". While black minstrel performers were once seen as the degraded victims of a racist spectacle, subsequent commentators could now celebrate these culture bearers for creating a subversive space for the advancement of their art and aesthetic. African-American minstrels, Karen Sotiropoulos observed, "did not just attempt to hook audiences with hokum; they subverted and manipulated stereotypes as they struggled to present black identity." This critical perspective has the performers looking over the jeering crowd into the eyes of sympathetic conspirators and giving them a wink to signal their mutual confidence.

Artistic dilemma

Race and sex were the pole stars of hokum, with booze and the law defining loose boundaries. Transgression was a given. How performers navigated through these waters varied from artist to artist. High and low culture had yet to converge as mainstream or popular culture. The convergence of performance styles, from different races that minstrelsy and by extension hokum represented, helped to define a central, ongoing tension in American culture. The cycle of rejection, accommodation, appropriation and authentication was set in motion. The infantilized and grotesque enactments and racist and misogynistic content caused many better educated observers of the day to dismiss both the Minstrel Show and hokum as simply vulgar. Some of the white artists, whose contributions to minstrelsy are most valued today, struggled to rise above its cruder forms in their lifetimes. Stephen Foster composed for years in obscurity, while the minstrel troupe leader Edwin P. Christy claimed credit for his songs. By 1852, Foster still wanted the pride of authorship, but wrote to Christy,

I had the intention of omitting my name on my Ethiopian songs, owing to the prejudice against them by some, which might injure my reputation as a writer of another style of music. But I find that by my efforts, I have done a great deal to build up a taste for the Ethiopian songs among refined people by making the words suitable to their taste, instead of the trashy and really offensive words which belong to some of that order.

The same contradictions and ambiguities were endured by African Americans like the composer James A. Bland, the actor Sam Lucas, and the bandleader James Reese Europe. The classically trained African-American composer Will Marion Cook, who toured throughout the United States and gave a command performance for King George V in England, struggled to raise his music to a public perception of distinction and merit, but was thwarted by marketing that distinguished author and music only by skin color.

Cook wrote what he called "real Negro melodies" and what he envisioned as "opera." He sought to market the syncopated sounds emanating from black expressive culture, but his compositions would be sold as "coon songs" suitable for variety stages. Cook's music fits most comfortably in the genre now known as "ragtime," but at the turn of the [20th] century, critics used the terms "ragtime" and "coon song" interchangeably. Like minstrelsy, the "coon song craze" sold racist stereotypes to mass audiences. Not unlike African-American minstrel performers, black songwriters capitulated in varying degrees to white racist expectation to market their music.[1]

The use of dialect or faux African-American (or Irish) speech patterns also caused many minstrel compositions to be lumped into categories with interchangeable "coon song" connotations. "Wake Nicodemus", published in 1864 by Henry Clay Work, in Chicago, could neatly fit into the modern definition of a protest song, and his later hits, such as "Marching Through Georgia", identified his strong abolitionist convictions (his father was famous as a stalwart supporter of the Underground Railroad). Yet many of his songs were minstrel show staples. His compositions were widely performed by Christy's Minstrels in particular, who appreciated compositions such as "Kingdom Coming". This song was "full of bright, good sense and comical situations in its 'darkey' dialect", as the publisher and songwriter George Frederick Root described it in his autobiography "The Story of a Musical Life".

There is no glossing over the fact that most "coon songs" reveled in ridicule. The reception of "coon songs", however, was by no means uniform. White performers embraced the "coon song craze" as it suited them. The North Carolina Piedmont pioneer Charlie Poole was an acrobatic jokester with a banjo beating out a "barbaric twang", but he did not perform the "coon songs" he covered in black dialect or in blackface. Poole preferred to hone his own identity and style. While his comedy marked him as hokum, his music was drawn from the "hillbilly" polyglot of Tin Pan Alley, marches, blues, Appalachian Scots Irish old-time fiddle tunes, two-steps, early vaudeville, Civil War chestnuts, event songs, murder ballads and the rest of the mix, with minstrel tunes another important source.

Hokum in early blues

After the First World War, the fledgling record industry split hokum off from its minstrel show or vaudeville context to market it as a musical genre, the hokum blues. Early practitioners surfaced in jug bands performing in the saloons and bordellos of Beale Street, in Memphis, Tennessee. Light-hearted and humorous jug bands like Will Shade's Memphis Jug Band and Gus Cannon's Jug Stompers played good-time, upbeat music on assorted instruments, such as spoons, washboards, fiddles, triangles, harmonicas, and banjos, all anchored by bass notes blown across the mouth of an empty jug. Their blues was rife with popular influences of the time and had none of the grit and plaintive "purity" of blues from the nearby Mississippi Delta. Cannon's classic composition "Walk Right In", originally recorded for Victor in 1930, resurfaced as a number one hit 33 years later, when the Rooftop Singers recorded it during the folk revival in New York's Greenwich Village, and a jug band boom ensued once more.

Hokum blues lyrics specifically poked fun at all manner of sexual practices, preferences, and eroticized domestic arrangements. Compositions such as "Banana in Your Fruit Basket", written by Bo Carter of the Mississippi Sheiks, used thinly veiled allusions, which typically employed food and animals as metaphors in a lusty manner worthy of Chaucer. The hilariously sexy lyric content usually steered clear of subtlety. "Bo Carter was a master of the single entendre", remarked the Piedmont blues guitar master "Bowling Green" John Cephas at Chip Schutte's annual guitar camp. The bottleneck guitarist Tampa Red was accompanied by Thomas A. Dorsey (performing as Barrelhouse Tom or Georgia Tom) playing piano when the two recorded "It's Tight Like That" for the Vocalion label in 1928. The song went over so well that the two bluesmen teamed up and became known as the Hokum Boys. Both previously performed in the band of the "Mother of the Blues", Ma Rainey, who had traveled the vaudeville circuits with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels as a girl, later taking Bessie Smith under her wing. The Hokum Boys recorded over 60 bawdy blues songs by 1932, most of them penned by Dorsey, who later picked up his Bible and became the founding father of black gospel. Dorsey characterized his hokum legacy as "deep moanin', low-down blues, that's all I could say!"

Hokum in early country music

While hokum surfaces in early blues music most frequently, there was some significant crossover culturally. When the Chattanooga-based "brother duet" the Allen Brothers recorded a hit version of "Salty Dog Blues", refashioned as "Bow Wow Blues" in 1927 for Columbia's 15,000-numbered "Old Time" series the label rushed out several new releases to capitalize on their success, but mistakenly issued them on the 14,000 series instead.

In fact, the Allen Brothers were so adept at performing white blues that in 1927, Columbia mistakenly released their "Laughin' and Cryin' Blues" in the "race" series instead of the "old-time" series. (Not seeing the humor in it, the Allens sued and promptly moved to the Victor label.) [2]

An early black string band, the Dallas String Band with Coley Jones, recorded the song "Hokum Blues" on December 8, 1928, in Dallas, Texas, featuring mandolin instrumentation. They have been identified both as proto bluesmen and as an early Texas country band and were likely to have been selling to both black and white audiences. Blind Lemon Jefferson and T-Bone Walker played in the Dallas String Band at various times. Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies, the seminal white Texas swing band, recorded a hokum tune with scat lyrics in the early 1930s, "Garbage Man Blues", which was originally known by the title the jazz composer Luis Russell gave it, "The Call of the Freaks". Bob Wills, who had performed in blackface as a young man, liberally used comic asides, whoops, and jive talk when directing his famous Texas Playboys. The Hoosier Hot Shots, Bob Skyles and the Skyrockets, and other novelty song artists concentrated on the comedic aspects, but for many up-and-coming white country musicians, like Emmett Miller, Clayton McMichen and Jimmie Rodgers, the ribald lyrics were beside the point. Hokum for these white rounders in the South and Southwest was synonymous with jazz, and the "hot" syncopations and blue notes were a naughty pleasure in themselves. The lap steel guitar player Cliff Carlisle, who was half of another "brother duet", is credited with refining the blue yodel song style after Jimmie Rodgers became the first country music superstar by recording over a dozen blue yodels. Carlisle wrote and recorded many hokum tunes and gave them titles such as "Tom Cat Blues", "Shanghai Rooster Yodel" and "That Nasty Swing". He marketed himself as a "hillbilly", a "cowboy", a "Hawaiian" or a "straight" bluesman (meaning presumably, black), depending on the audience for whom he was playing and where he played.

The radio "barn dances" of the 1920s and 1930s interspersed hokum in their variety show broadcasts. The first blackface comedians at the WSM Grand Ole Opry were Lee Roy "Lasses" White and his partner, Lee Davis "Honey" Wilds, starring in the Friday night shows. White was a veteran of several minstrel troupes, including one organized by William George "Honeyboy" Evans and another led by Al G. Field, who also employed Emmett Miller. By 1920, White was leading his own outfit, the All Star Minstrels. Lasses and Honey joined the Grand Ole Opry cast in 1932. When Lasses moved on to Hollywood in 1936 to play the role of a silver-screen cowboy sidekick, Wilds stayed on in Nashville, corking up and playing blues on his ukulele with his new partner Jam-Up (first played by Tom Woods and subsequently by Bunny Biggs). Wilds organized the first Grand Ole Opry–endorsed tent show in 1940. For the next decade, he ran the touring show, with Jam-Up and Honey as the headliners. Pulling a forty-foot trailer behind a four-door Pontiac and followed by eight to ten trucks, Wilds took the tent show from town to town, hurrying back to Nashville on Saturdays for his Opry radio appearances. Many country musicians, like Uncle Dave Macon, Bill Monroe, Eddy Arnold, Stringbean and Roy Acuff, toured with the Wilds tent shows from April through Labor Day. As Wilds's son David said in an interview,

Music was a part of their act, but they were comedians. They would sing comedic songs, a la Homer and Jethro. They would add odd lyrics to existing songs, or write songs that were intended to be comedic. They were out there to come onstage, do five minutes of jokes, sing a song, do five minutes of jokes, sing another song and say, "Thank you, good night", as their segment of the Grand Ole Opry. Almost every country band during that time had some guy who dressed funny, wore a goofy hat, and typically played slide guitar.[3]

Legacy

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2020) |

Although the sexual content of hokum is generally playful by modern standards, early recordings were marginalized for both sexual suggestiveness and "trashy" appeal, but they flourished in niche markets outside the mainstream. "Jim Crow" segregation was still the norm in much of the United States, and racial, ethnic and class bias was embedded in the popular entertainment of the time. Prurience was seen as more antisocial than prejudice. Record companies were more concerned about selling records than stigmatizing artists and minority audiences. Modern audiences might be offended by the packaged exploitation these stock caricatures offered, but in early 20th-century America, it paid for performers to play the fool. Audiences were left on their own to interpret whether they themselves were sharing the joke or were the butts of it. While "race" musicians traded in "coon songs" crafted for commercial consumption by catering to white prejudice. "Hillbilly" musicians were similarly marketed as "rubes" and "hayseeds". Class distinctions bolstered these portrayals of gullible rural folk and witless southerners. Assimilation of African Americans and cultural appropriation of their artistic and cultural creations were not yet equated by the emerging entertainment industry with racism and bigotry.

The eventual success of African-American musical productions on Broadway, like Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle's "Shuffle Along" in 1921, helped to usher in the swing jazz era. This was accompanied by a new sense of sophistication that eventually disdained hokum as backward, insipid, and perhaps most damningly, corny. Audiences began to change their perceptions of authentic "Negro" artistry. White comedians like Frank Tinney and singers like Eddie Cantor (nicknamed Banjo Eyes) continued to work successfully in blackface on Broadway. They even branched out into vaudeville-based sensations like the Ziegfeld Follies and the emerging film industry, but cross-racial comedy became increasingly out of fashion, especially onstage. On the other hand, it is impossible to imagine that the success of comics such as Pigmeat Markham or Damon Wayans or bandleaders like Cab Calloway or Louis Jordan does not owe some debt to hokum. White performers have thoroughly absorbed the lessons of hokum as well, with the "top banana" Harry Steppe, singers like Louis Prima and Leon Redbone or comedian Jeff Foxworthy being prime examples. Offstage it is by no means extinct either, or practiced only by members of one race parodying another race. The Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, a New Orleans Mardi Gras krewe, has marched on Fat Tuesday since 1900, dressed in raggedy clothes and grass skirts with their faces blackened. Zulu is now the largest predominantly African-American organization marching in the annual Carnival celebration. While the minstrel show, burlesque, vaudeville, variety, and the medicine show have left the scene, hokum is still here.

Rural stereotypes continued to be fair game. Consider the phenomenal success of the syndicated television program Hee Haw, produced from 1969 until 1992. Writer Dale Cockrell has called this a minstrel show in "rube-face". It featured country music stars, curvaceous comedians, and banjo playing bumpkins whose pickin' and grinnin' picked on city slickers and grinned at the buxom All Jugs Band. The rapid fire one-liners, Laugh-In rapid cross-cutting, animations of barnyard animals, hayseed humor and continuous parade of country, bluegrass, and gospel performers appealed to an untapped demographic that was older and more rural than the young, urban "hip" audience broadcasters were routinely cultivating. It is still in syndication today, and is one of the most successful syndicated programs ever. Admirers of hokum warmed to its slyness and the seeming innocence that provided a context for simplistic shenanigans. In the rural south in particular, hokum held on. Cast members like Stringbean and Grandpa Jones were familiar with hokum (and blackface), and if bands named the "Clodhoppers" or the "Cut Ups" and other country cousins of this comedic form are fewer in number today, their presence is still a clue to the country and western, bluegrass, and string band tradition of mixing stage antics, broad parodies and sexual allusions with music.

Examples of hokum

|

|

NB. Various music historians describe many of these songs as dirty blues.

Hokum compilations

- Please Warm My Weiner, Yazoo L-1043 (cover art by Robert Crumb) (1992)

- Hokum: Blues and Rags (1929–1930), Document 5392 (1995)

- Hokum Blues: 1924–1929, Document 5370 (1995)

- Raunchy Business: Hot Nuts & Lollypops, Sony (1991)

- Let Me Squeeze Your Lemon: The Ultimate Rude Blues Collection, (2004)

- Take It Out Too Deep: Rufus & Ben Quillian (Blue Harmony Boys) (1929–30)

- Vintage Sex Songs, Primo 6077 (2008)

Other collections containing hokum

- Traditional Country Music Makers, Vol. 20: Memphis Yodel, Magnet MRCD 020 (Cliff Carlisle and other artists)

- White Country Blues, 1926–1938: A Lighter Shade of Blue, Sony (1993)

- Booze and the Blues, Legacy Roots n' Blues series, Sony (1996)

- Good For What Ails You: Music of the Medicine Shows 1926–1937, Old Hat Records CD-1005 (2005)

See also

References

- ^ "Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America" by Karen Sotiropoulos (Harvard University Press, 2006)

- ^ Wolfe, Charles (1998). Entry on the Allen Brothers. The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, ed. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Grant Alden. Interview with David Wilds. No Depression, issue 4, summer 1996.

Sources

- Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507832-2.

- Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6300-5.

- The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. DuBois (Penguin Classics, New York: Penguin Books, reprinted April 1996) ISBN 0-14-018998-X.

- Reminiscing with Sissle and Blake by Robert Kimball and William Bolsom (The Viking Press, New York, 1973)

- Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America by Karen Sotiropoulos (Harvard University Press, 2006)

- Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World by Dale Cockrell (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- The Story of a Musical Life: An Autobiography by George F. Root (Cincinnati: John Church Co., 1891; reprinted by AMS Press, New York, 1973). ISBN 0-404-07205-4.

- We'll Understand It Better By and By: Pioneering African American Gospel Composers edited by Bernice Johnson Reagon. Wade in the Water Series. (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C, 1993).

- Black Gospel: An Illustrated History of the Gospel Sound by Vic Broughton (Blandford Press, New York, 1985)

- Where Dead Voices Gather by Nick Tosches, 2001, Little, Brown, Boston. ISBN 0-316-89507-5. On Emmett Miller.

- A Good Natured Riot: The Birth of the Grand Ole Opry by Charles K. Wolfe (Country Music Foundation Press and Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, Tennessee, 1999)

- Bluegrass Breakdown : The Making of the Old Southern Sound by Robert Cantwell (University of Illinois Press, Chicago, 1984, reprinted 2003).

- It Came from Memphis by Robert Gordon (Pocket Books, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1995).

- Stephen Foster: America's Troubadour by John Tasker Howard. (Thomas Y. Crowell, New York, 1934; 2nd ed., 1953)

- The Encyclopedia of Country Music edited by Paul Kingsbury (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998)

- Minstrel Banjo Style various artists, liner notes, Rounder Records ROUN0321, 1994

- You Ain't Talkin' to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music liner notes by Henry Sapoznik, Columbia Legacy Recordings C3K 92780, 2005

- Good for What Ails You: Music of the Medicine Shows 1926–1937 liner notes by Marshall Wyatt, Old Hat Records CD-1005 (2005)