Home of the Brave (1949 film)

| Home of the Brave | |

|---|---|

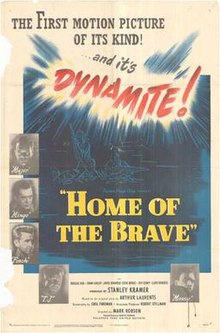

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mark Robson |

| Screenplay by | Carl Foreman |

| Based on | Home of the Brave (play) 1945 play by Arthur Laurents |

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer Robert Stillman |

| Starring | Douglas Dick Frank Lovejoy James Edwards Steve Brodie Jeff Corey Lloyd Bridges |

| Cinematography | Robert De Grasse |

| Edited by | Harry W. Gerstad |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

Production company | Stanley Kramer Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $370,000[1] or $235,000[2] |

| Box office | $2.5 million[1][3] |

Home of the Brave is a 1949 war film based on a 1946 play by Arthur Laurents. It was directed by Mark Robson, and stars Douglas Dick, Jeff Corey, Lloyd Bridges, Frank Lovejoy, James Edwards, and Steve Brodie. The original play featured the protagonist being Jewish, rather than black. The National Board of Review named the film the eighth best of 1949. The film takes its name from the last line of the "Star Spangled Banner" "And the home of the brave?"

Home of the Brave managed to combine three of the top film genres of 1949: the war film, the psychological drama, and the problems of African-Americans. The film utilizes the recurrent theme of a diverse group of men being subjected to the horror of war and their individual reactions, in this case, to the hell of jungle combat against the Japanese in World War II.

Plot

Undergoing psychoanalysis by an Army psychiatrist (Corey), paralyzed Black war veteran Private Peter Moss (Edwards) begins to walk again only when he confronts his fear of forever being an "outsider".

The film uses flashback techniques to show Moss, an Engineer topography specialist assigned to a reconnaissance patrol who are clandestinely landed from a PT boat on a Japanese-held island in the South Pacific to prepare the island for a major amphibious landing. The patrol is led by a young major (Dick), and includes Moss's lifelong friend Finch (Bridges), whose death leaves him racked with guilt; bigot Corporal T.J. (Brodie); and the sturdy but troubled Sergeant Mingo (Lovejoy).

When the patrol is discovered, Finch is left behind and captured by the Japanese. They force Finch to cry out to the patrol. Finch later escapes but he dies in Moss's arms. In a firefight with the Japanese, Mingo is wounded in the arm, and Moss is unable to walk. T.J. carries Moss to the returning PT boat that covers the men with its twin .50 caliber machine guns.

In the film's climax, the doctor forces Moss to overcome his paralysis by yelling a racial slur. From this point on, Moss will never again bow to prejudice. At the end of the movie, Mingo and Moss decide to go into business together as a civilians.

Cast

- Jeff Corey as Doctor

- James Edwards as Private Peter Moss

- Lloyd Bridges as Finch

- Douglas Dick as Major Robinson

- Frank Lovejoy as Sergeant Mingo

- Steve Brodie as T.J. Everett

- Cliff Clark as Colonel Baker

Production

Arthur Laurents spent World War II with the Army Pictorial Service based at the film studio in Astoria, Queens, and rose to the rank of sergeant. After his discharge, he wrote a play called Home of the Brave in nine consecutive nights that was inspired by a photograph of GIs in a South Pacific jungle. The drama about anti-Semitism in the military opened on Broadway on December 27, 1945, and ran for 69 performances.[4]

When Laurents sold the rights to Hollywood, he was told that the lead character would be turned from Jewish into black because "Jews have been done".[5]

Producer Stanley Kramer filmed in secrecy under the working title of High Noon. The film was completed in thirty days, for the cost of US$525,000, with Kramer using three different units at the same time.[6] The majority of the film was made on indoor sets, except for the climax that took place on Malibu beach with a former navy PT boat. Associate producer Robert Stillman financed the film with the help of his father, without the usual procedure of borrowing funds from banks.[7]

Director Robson, who had begun his directing career with several Val Lewton RKO horror films, brings a frightening feeling to the claustrophobic jungle set, with Dimitri Tiomkin providing an eerie choral rendition of Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child performed by the Jester Hairston choir as the patrol escapes their Japanese pursuers.

In the movie's final scene, Sergeant Mingo recites Eve Merriam's 1943 poem The Coward to Private Moss in friendship: "Divided we fall, united we stand; coward, take my coward's hand." The New York Herald Tribune reported that a man named Herbert Tweedy imitated the sound of twelve different birds native to the South Pacific for the film.[8]

Reception

Home of the Brave received acclaim from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a rating of 98% from 40 reviews.[9]

Accolades

The film gained the prize of the International Catholic Organization for Cinema (OCIC) at the Knokke Experimental Film Festival in 1949.[10] According to this jury, this was a film "most capable of contributing to the revival of moral and spiritual values of humanity". "We all know the definition of this award "for the production that has made the greatest contribution to the moral and spiritual betterment of humanity". it differs from the other awards, when are normally given for artistic merit. Art for Art's sake is not the object, but rather art for the sake of man, the whole of man, heart and soul. Pious dullness is not the aim (...).[11]

In 1959, famed stand-up comedian and social critic Lenny Bruce, as part of a monologue on The Steve Allen Show, criticized Hollywood for its exploitation of race relations just for the sake of exploiting and without really saying anything, but he singled out Home of the Brave as being a good picture that touched on racial issues that were important.[12]

Legacy

In a topical decision, President Truman's Executive Order 9981 had ordered the U.S. Armed Forces to be fully integrated in 1948.

Notes

- ^ a b "STAR SYSTEM 'ON THE WAY OUT'". The Mail. Adelaide. 14 October 1950. p. 8 Supplement: Sunday Magazine. Retrieved 4 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Champlin, C. (Oct 10, 1966). "Foreman hopes to reverse runaway". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 155553672.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1949". Variety. 4 January 1950. p. 59.

- ^ pp. 41-49 Laurents, Arthur, Original Story By. New York: Alfred A. Knopf 2000

- ^ "A life in musicals: Arthur Laurents". TheGuardian.com. 31 July 2009.

- ^ p. 22 Deane, Pamala S. James Edwards: African American Hollywood Icon 2009 McFarland

- ^ p. 463 Gevinson, Alan The American Film Institute Catalog 1997 University of California Press

- ^ p. 23 Deane, Pamala S. James Edwards: African American Hollywood Icon 2009 McFarland

- ^ "Home of the Brave". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "Get Belgium Oscars", p.10, in Showmen's Trade Review, July 16, 1949

- ^ Johanes, "The Venice Film Festival", p.33, in International Film Review, Brussels, 1949.

- ^ LENNY BRUCE ON THE STEVE ALLEN SHOW APRIL 5, 1959, retrieved 2022-04-06

External links

- 1949 films

- 1940s war drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American war drama films

- Films about psychiatry

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films directed by Mark Robson

- Films produced by Stanley Kramer

- Films scored by Dimitri Tiomkin

- Films set in Oceania

- Films with screenplays by Carl Foreman

- Pacific War films

- United Artists films

- 1949 drama films

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s American films