Hugh de Neville

Hugh de Neville | |

|---|---|

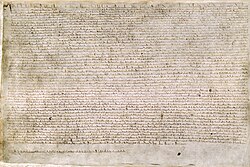

The church at Waltham Abbey, where Hugh de Neville was buried | |

| Chief Forester of England | |

| In office 1198–1216 & 1224–1229/34 | |

| Sheriff of Oxfordshire | |

| In office 1196–1199 | |

| Sheriff of Essex and Sheriff of Hertfordshire | |

| In office 1197–1200 | |

| Sheriff of Hampshire | |

| In office 1209 – c. 1213 | |

| Sheriff of Lincolnshire | |

| In office 1227–1227 | |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 1234 |

| Resting place | Waltham Abbey |

| Spouse(s) | (1) Joan de Cornhill (2) Beatrice |

| Children | John de Neville Henry de Neville Herbert de Neville Joan |

Hugh de Neville[a] (died 1234) was the Chief Forester under the kings Richard I, John and Henry III of England; he was the sheriff for a number of counties. Related to a number of other royal officials as well as a bishop, Neville was a member of Prince Richard's household. After Richard became king in 1189, Neville continued in his service and accompanied him on the Third Crusade. Neville remained in the royal service following Richard's death in 1199 and the accession of King John to the throne, becoming one of the new king's favourites and often gambling with him. He was named in Magna Carta as one of John's principal advisers, and considered by a medieval chronicler to be one of King John's "evil counsellors".[2] He deserted John after the French invasion of England in 1216 but returned to pledge his loyalty to John's son Henry III after the latter's accession to the throne later that year. Neville's royal service continued until his death in 1234, though by then he was a less significant figure than he had been at the height of his powers.

Early life and career

[edit]Neville was the son of Ralph de Neville, a son of Alan de Neville, who was also Chief Forester.[3] Hugh had a brother, Roger de Neville, who was part of Hugh's household from 1202 to 1213, when Roger was given custody of Rockingham Castle by King John.[4] Another brother was William, who was given some of Hugh's lands in 1217.[5] Hugh, Roger, and William were related to a number of other royal officials and churchmen, most notable among them Geoffrey de Neville, who was a royal chamberlain, and Ralph Neville, who became Bishop of Chichester.[6] Hugh de Neville employed Ralph de Neville at the start of Ralph's career, and the two appear to have remained on good terms throughout the rest of Hugh's life.[7]

Hugh de Neville was a member of the household of Prince Richard, later Richard I,[8] and also served Richard's father, King Henry II at the end of Henry's reign, administering two baronies for the king.[9] Neville accompanied Richard on the Third Crusade; he was one of the few knights who fought with the king on 5 August 1192 outside the walls of Jaffa, when the king and a small force of knights and crossbowmen fought off a surprise attack by Saladin's forces.[10] Neville's account of events was a source for the chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall's entries on Richard's activities in the Third Crusade.[8][b]

In 1194 Neville acquired the wardship of Joan de Cornhill, daughter of Henry de Cornhill, and married her four years later. Also in 1194 he was given custody of the town of Marlborough in Wiltshire,[11] and in 1196 he was appointed as Sheriff of Oxfordshire.[6] He was also named in 1197 as Sheriff of Essex and Sheriff of Hertfordshire, offices he held until some time in 1200.[9]

Chief Forester

[edit]

Neville was appointed as Chief Forester under King Richard I[12] in 1198.[13] As the official in charge of the royal forests, he held one of the four great offices of the state: the others were the justiciar, the chancellor, and the treasurer. The forester was responsible for enforcing the forest law—the special law that applied to the royal forests[c]—and presided over the forest justices, who held forest eyres. There was also a special forest exchequer, or forest treasury.[15] In 1198 Neville presided over an Assize of the Forest that was described by the chronicler Roger of Howden as greatly oppressive.[16] The revenues could be considerable; in 1198 the forest eyre brought in £1,980.[17] Neville stated in 1208 that over the previous six and a half years the amount raised by the various revenues of the forests had been £15,000;[18] in 1212 it had been £4,486.[17] Forest law was resented by the king's subjects, not just for its severity but also because of the large extent of the kingdom that it encompassed. It covered not just woodlands, but by the end of the 12th century between a quarter and a third of the whole kingdom. This extent enabled the Norman and Angevin kings to use the harsh punishments of forest law to extract large sums of money for their government.[14]

Neville continued to hold the office of Chief Forester under King John and he was often the king's gambling partner.[19] He was a frequent witness to John's royal charters.[20] Under John, Neville was named to the offices of Sheriff of Hampshire in 1210,[9] and Sheriff of Cumberland, offices of which he was deprived in 1212.[21] He was also reappointed to the shrievalties of Essex and Hertfordshire in 1202, holding them until 1203.[22]

In 1210 King John fined Neville 1,000 marks because he had allowed Peter des Roches, the Bishop of Winchester, to enclose some hunting grounds without royal permission; although Roches was close to the king, his action was an infringement of the royal forests. Neville's large fine was probably a warning that the king was serious about enforcing the forest law; it was eventually rescinded.[19] In 1213 Neville was placed in charge of the seaports along the southwest English coast from Cornwall to Hampshire,[22] but some time in 1213 it appears that he fell from royal favour, although the circumstances are unknown. A fine of 6,000 marks was assessed on him for allowing two prisoners to escape, as well as other unrecorded offences, although the king did subsequently remit 1,000 marks of the fine. In 1215 Neville lost his office of chief forester.[23] He was present at Runnymede for the signing of Magna Carta and was mentioned in the preamble as one of King John's councillors,[4] as well as serving as a witness to the document.[9] Roger of Wendover, a chronicler writing in 1211, listed Neville as one of King John's "evil counsellors".[2]

John's later reign and service under King Henry III

[edit]John's style of ruling, and his defeats in the Anglo-French War in 1214, had alienated many of his nobles.[24] Initially, a faction of the barons forced John to agree to Magna Carta to secure less capricious government from the king.[25] John, however, after agreeing to their demands, secured the annulment of the charter from the papacy in late 1215. The opposition magnates then invited Prince Louis of France to take the English throne, and Louis arrived in England with an army in May 1216.[24]

Neville joined the rebel barons in 1216,[1] shortly after Prince Louis invaded England.[26] Neville surrendered Marlborough Castle, a royal castle in his custody, to Prince Louis in mid-1216. Louis had not besieged the castle, and it appears that Neville took the initiative in making overtures to the prince. When John heard of the change of sides, he confiscated all of Neville's lands held directly from the king on 8 July 1216. On 4 September 1216 the king further confiscated lands belonging to other rebels that had been granted to Neville before the surrender of Marlborough; some were re-granted to Neville's brother William. Hugh de Neville's son, Herbert, also joined the rebels.[5]

After King John's death in October 1216, Neville and his son made their peace with the new king, Henry III, John's son. Both men had their lands restored in 1217, but the offices that the elder Neville had held were not returned quickly. Custody of some royal forests was returned by 1220, but the office of Chief Forester was not returned until some time later.[27] In 1218 Neville was supposed to have had the forest of Rockingham returned to his custody, but William de Forz, the Count of Aumale, refused to return it.[28] It was not until 1220 that de Neville managed to recover his custody of Rockingham forest.[29] By 1224 Neville was once more Chief Forester,[30] but he never regained the power and influence that he had held under John.[8] When he lost the office for the second time is unclear. The historian C. R. Young states that he held the office until his death in 1234 when it passed to his son John,[27] but Daniel Crook, writing in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, claims that Neville lost the forester office in 1229, to be replaced by John of Monmouth and Brian de Lisle.[9][d] He also served as Sheriff of Lincolnshire.[22]

Records and lands

[edit]Neville's household records for 1207 survive, detailing his itinerary for the year; in one eight-week period his household visited eleven different towns.[32] In 1204 his wife offered the king 200 chickens for the right to sleep one night with her husband, an obligation recorded in the royal records.[1][e] The historian Daniel Crook suggests that this shows that Joan Neville was one of the barons' wives who attracted King John's sexual attentions.[9]

Neville inherited lands in Lincolnshire worth one half of a knight's fee. These were augmented with gifts from Richard and John, much of which were in Essex. He also acquired lands in Surrey and in Somerset, and his marriage to Joan brought him estates in Essex.[35] Joan's lands also brought him into conflict with Falkes de Breauté, the husband of Joan's younger sister and co-heiress, and the two brothers-in-law were involved in lawsuits over their wives' lands for more than five years.[36] Joan and her sister were also co-heiresses to the barony of Courcy, in right of their mother Alice de Courcy.[9]

Death and legacy

[edit]Neville's first wife, Joan de Cornhill, died after December 1224. Some time before April 1230 he married secondly Beatrice, the widow of Ralph de Fay and one of the five daughters of Stephen of Turnham. Joan and Neville had at least three sons—John, Henry[9] and Herbert.[5] Neville also had a daughter named Joan.[9]

Neville died in 1234,[3] although his death was incorrectly recorded by Matthew Paris as occurring in 1222.[f] Neville was buried at Waltham Abbey, of which he had been a patron.[9] Besides Waltham, he also made gifts to Christ Church Priory in Canterbury, Bullington Priory in Lincolnshire, and St Mary's Nunnery, Clerkenwell.[37] The historian Sidney Painter said of Neville's career during John's reign that "a strong argument could be advanced for the thesis that the royal official who wielded the most actual power during John's reign was the chief forester, Hugh de Neville".[38] Another historian, J. R. Maddicott, states that Neville was head of "one of the most detested branches of royal administration".[39]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sometimes Hugh Neville[1]

- ^ The later medieval writer Matthew Paris recorded a colourful story about Neville encountering a lion while on crusade. This story may have been made up by Paris from the fact that Neville used a lion on his seal, since no earlier writer mentions this story.[9]

- ^ Forest law was designed to protect the habitat of the deer and other hunted animals. It was unrelated to the customs and common law of England and its punishments were quite severe compared to the normal punishments of the common law.[14]

- ^ De Lisle was Neville's deputy as chief forester in 1225.[31]

- ^ Neville's entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states that the fine was 200 shillings,[9] but the original Latin of the record states plainly "Uxor Hugonis de Nevill' dat domino Regi CC. gallinas eo quod possit jacere una nocte cum domino suo Hugone de Nevill'",[33] and "CC. Gallinas" in that sentence is "200 Hens".[34]

- ^ This error led some earlier historians to postulate two different Hugh de Nevilles—the forester and a son also named Hugh. This disproved theory then had the elder Hugh dying in 1222 and the invented son dying in 1234.[9]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Warren King John p. 190

- ^ a b Vincent "King John's evil counsellors" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ a b Young Making of the Neville Family p. xi

- ^ a b Young Making of the Neville Family p. 30

- ^ a b c Young Making of the Neville Family p. 31

- ^ a b Young Making of the Neville Family pp. 18–19

- ^ Young Making of the Neville Family p. 79

- ^ a b c Young Making of the Neville Family pp. 24–25

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Crook "Neville, Hugh de" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Gillingham Richard I pp. 215–216

- ^ Young Making of the Neville Family pp. 25–26

- ^ Turner King John p. 45

- ^ Young Royal Forests p. 38

- ^ a b Saul "Forest" Companion to Medieval England pp. 105–107

- ^ Turner King John p. 61

- ^ Young Royal Forests pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Young Royal Forests p. 39

- ^ Turner King John p. 84

- ^ a b Warren King John p. 145

- ^ Turner King John pp. 57–58

- ^ Young Making of the Neville Family p. 29

- ^ a b c Cokayne Complete Peerage IX pp. 479–480

- ^ Young Royal Forests pp. 50–51

- ^ a b Huscroft Ruling England pp. 150–151

- ^ Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings p. 64

- ^ Carpenter Minority of Henry III p. 12

- ^ a b Young Making of the Neville Family p. 32

- ^ Carpenter Minority of Henry III p. 72

- ^ Carpenter Minority of Henry III p. 199

- ^ Young Royal Forests p. 70

- ^ Coss Origins of the English Gentry pp. 115–116

- ^ Bartlett England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings p. 142

- ^ Cokayne Complete Peerage IX p. 480 footnote g

- ^ Latham Revised Medieval Latin Word-List p. 207

- ^ Young Making of the Neville Family p. 33

- ^ Young Making of the Neville Family p. 47

- ^ Cokayne Complete Peerage IX p. 480 footnote j

- ^ Quoted in Young Making of the Neville Family p. 24

- ^ Maddicott "Oath of Marlborough" English Historical Review p. 316

References

[edit]- Bartlett, Robert C. (2000). England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings: 1075–1225. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822741-8.

- Carpenter, David (1990). The Minority of Henry III. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07239-1.

- Cokayne, George E. (1982). The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct, or Dormant. Vol. IX (Microprint ed.). Gloucester, UK: A. Sutton. ISBN 0-904387-82-8.

- Coss, Peter (2003). The Origins of the English Gentry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82673-X.

- Crook, David (2004). "Neville, Hugh de (d. 1234)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (revised January 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19942. Retrieved 1 December 2017. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Gillingham, John (1999). Richard I. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07912-5.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Latham, R. E. (1965). Revised Medieval Latin Word-List: From British and Irish Sources. London: British Academy. OCLC 299837723.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2011). "The Oath of Marlborough, 1209: Fear, Government and Popular Allegiance in the Reign of King John". English Historical Review. 126 (519): 281–318. doi:10.1093/ehr/cer076.

- Saul, Nigel (2000). "Forest". A Companion to Medieval England 1066–1485. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2969-8.

- Turner, Ralph V. (2005). King John: England's Evil King?. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3385-7.

- Vincent, Nicholas (2004). "King John's Evil Counsellors (act. 1208–1214)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95591. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 1 December 2017. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Warren, W. L. (1978). King John. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03643-3.

- Young, Charles R. (1996). The Making of the Neville Family in England 1155–1400. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-668-1.

- Young, Charles R. (1979). The Royal Forests of Medieval England. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-7760-0.