James Herriot

James Herriot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | James Alfred Wight 3 October 1916 Sunderland, County Durham, England |

| Died | 23 February 1995 (aged 78) Thirlby, North Yorkshire, England |

| Pen name | James Herriot |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | English |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | RCVS |

| Alma mater | Glasgow Veterinary College |

| Period | 1940–1992 |

| Subject |

|

| Spouse |

Joan Catherine Anderson Danbury

(m. 1941) |

| Children | 2 |

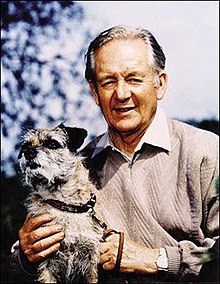

James Alfred Wight OBE FRCVS (3 October 1916 – 23 February 1995), better known by his pen name James Herriot, was a British veterinary surgeon and author.

Born in Sunderland, Wight graduated from Glasgow Veterinary College in 1939, returning to England to become a veterinary surgeon in Yorkshire, where he practised for almost 50 years. He is best known for writing a series of eight books set in the 1930s–1950s Yorkshire Dales about veterinary practice, animals, and their owners, which began with If Only They Could Talk, first published in 1970. Over the decades, the series of books has sold some 60 million copies.[1]

The franchise based on his writings was very successful. In addition to the books, there have been several television and film adaptations of Wight's books, including the 1975 film All Creatures Great and Small; a BBC television series of the same name, which ran 90 episodes; and a 2020 UK Channel 5 series, also of the same name.[2]

Life

[edit]James Alfred Wight, who was called "Alf" for short, was born on 3 October 1916 in Sunderland, County Durham, England.[3] The family moved to Glasgow when James was a child, and he lived there happily until leaving for Sunderland, and then Thirsk in North Yorkshire, England, in 1940. He had a "soft, lilting Scottish accent," according to actor Christopher Timothy, who portrayed James Herriot in the 1978 series.[4]

Wight attended Yoker Primary School and Hillhead High School.[5] When he was a boy in Glasgow, one of Wight's favourite pastimes was walking with his dog, an Irish Setter, in the Scottish countryside and watching it play with his friends' dogs. He later wrote: "I was intrigued by the character and behaviour of these animals... [I wanted to] spend my life working with them if possible." At age 12, he read an article in Meccano Magazine about veterinary surgeons and was captivated with the idea of a career treating sick animals. Two years later, in 1930, he decided to become a vet after the principal of Glasgow Veterinary College gave a lecture at his high school.[6]

Wight married Joan Catherine Anderson Danbury on 5 November 1941 at St Mary's Church, Thirsk.[7]

After they returned to Thirsk, Wight "carried on TB testing [of] cows in Wensleydale and the top floor of 23 Kirkgate became Joan and Alf’s first home".[5] The couple had two children.[8]: 148, 169, 292

Veterinary practice

[edit]Wight took six years to complete the five-year programme at Glasgow Veterinary College. He failed several of his classes on the first try (surgery, pathology, physiology, histology, animal husbandry). His setback was partly because of a recurring gastrointestinal problem, which required multiple operations.[1] He graduated on 14 December 1939.[5]

In January 1940, Wight joined a veterinary practice in Sunderland, working for J. J. McDowall.[5] He decided that he would prefer a rural practice and accepted a position in July, based at 23 Kirkgate in Thirsk, Yorkshire, near the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors. The practice owner, Donald Sinclair, had enlisted in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and was soon to leave for training; he gave Wight all the practice's income in return for Wight's looking after it during his absence.[9] (His brother, Brian Sinclair, was not yet a vet.) After Sinclair was discharged from the RAF four months later, he asked Wight to stay permanently with the practice, offering a salaried partnership, which Wight accepted.[10]

Wight enlisted in the RAF in November 1942. He did well in his training and was one of the first in his flight to fly solo. After undergoing surgery on an anal fistula in July 1943, he was deemed unfit to fly combat aircraft and was discharged as a leading aircraftman the following November. He joined his wife at her parents' house, where she had lived since he left Thirsk. They lived there until the summer of 1945, when they moved back to 23 Kirkgate after Sinclair and his wife moved to a house of their own. In 1953, the family moved to a house on Topcliffe Road, Thirsk. Wishing for more privacy as the popularity of All Creatures Great and Small increased, in 1977 Wight and his wife moved again, to the smaller village of Thirlby, about 4 miles (6.4 km) from Thirsk. Wight lived there until his death in 1995.[8]

Wight became a full partner in the Thirsk practice in 1949 and retired from full-time practice in 1980 but continued to work part time.[5] He fully retired in 1989 (or 1990 according to some sources); by then, he had worked in his field for roughly 50 years.[1][5]

Death

[edit]In Wight's will, his share of the practice passed to his son, Jim Wight, also a vet. Alf Wight had been diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1991 and was treated in the Friarage Hospital in Northallerton.[8]: 345, 352 On 23 February 1995, he died at his home in Thirlby as a result of the cancer,[11][12] leaving an estate valued for probate at £5,425,873 (equivalent to £13,174,807 in 2023).[13][14] His remains were cremated and scattered on Sutton Bank.[5] His wife's health declined after his death, and she died on 14 July 1999.[15]

Remembering Alf Wight

[edit]In 2001, a book by Wight's son, Jim, was published. A review of The Real James Herriot: A Memoir of My Father noted, "Wight portrays his father as a modest, down-to-earth and generous man, utterly unchanged by fame, a private individual who bottled up his emotions, which led to a nervous breakdown and electroshock therapy in 1960."[16]

Wight's obituary confirmed his modesty and preference to stay away from the public eye. "It doesn't give me any kick at all," he once said. "It's not my world. I wouldn't be happy there. I wouldn't give up being a vet if I had a million pounds. I'm too fond of animals."[17] By 1995, some 50 million of the James Herriot books had been sold. Wight was well aware that clients were unimpressed with the fame that accompanied a best-selling author. "If a farmer calls me with a sick animal, he couldn't care less if I were George Bernard Shaw," Wight once said.[18]

Career as an author

[edit]Although Wight claimed in the preface of James Herriot's Yorkshire that he had begun to write only after his wife encouraged him when he was 50, he in fact kept copious diaries as a child, as a teenager wrote for his school's magazine, and wrote at least one short story during his college years.[19] In the early 1960s he began analysing the books of successful authors that he enjoyed reading, such as P. G. Wodehouse and Conan Doyle, to understand different writing styles.[19] During this time he also began writing more seriously, composing numerous short stories and, in his own words, 'bombarding' publishers with them.[19]

Based on the year when he started work in Thirsk, the stories in the first two books would have taken place early during the Second World War. Wight preferred to have them take place in a quieter era so he set them in pre-war years.[1]

The author required a pseudonym because the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons' regulations prevented vets from any type of advertising. A reliable source states that he "chose the name after attending a football match in which the Scotland internationalist Jim Herriot played in goal for Birmingham City."[20]

Wight's early efforts at having his writing published were unsuccessful, which he later explained by telling Paul Vallely in a 1981 interview for the Sunday Telegraph Magazine, "...my style was improving but [...] my subjects were wrong."[19] Choosing a subject where he was more experienced, in 1969 he wrote If Only They Could Talk, a collection of stories about his experiences as a young veterinary surgeon in the Yorkshire Dales. The book was published in the United Kingdom in 1970 by Michael Joseph Ltd. Wight followed it up with It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet in 1972. Sales were slow until Thomas McCormack of St. Martin's Press in New York City received a copy and arranged to have both books published as one volume in the United States that year. Wight named this volume All Creatures Great and Small from the second line of the hymn "All Things Bright and Beautiful".[8] The book was a huge success.

Achieving success

[edit]Wight wrote seven more books in the series started by If Only They Could Talk. In the United States, the first six books of the original series were thought too short to publish independently. Most of the stories were collected into three omnibus volumes; the final two books were published separately. The last book of the series, Every Living Thing, sold 650,000 copies in six weeks in the United States and stayed on The New York Times Best Seller list for eight months.[19]

Recent research indicates that the first two books sold only a few thousand copies in the UK at first. "It was a New York publisher [St. Martin's Press] who changed the childish-looking cover art[,] combined the works under the title All Creatures Great and Small," and reaped the benefits when the work achieved best-seller status in the US.[21] Its US editor, Tom McCormack, quoted in a book based on interviews of American publishers, said the title choice was made after he sought suggestions from colleagues, related to nature, and "a British guy in our marketing department, Michael Brooks", spoke about the hymn, reciting its first verse. However, in a 1976 BBC interview Wight said "this was my daughter's title" and "she thought that one out".[22][23][24]

Contrary to widespread belief, Wight's books are only partially autobiographical, with many of the stories only loosely based on real events or people. Where stories do have a basis in genuine veterinary cases, they are frequently ones that Wight attended in the 1960s and 70s. Most of the stories are set in the fictional town of Darrowby, which Wight described as a composite of Thirsk, its nearby market towns Richmond, Leyburn, and Middleham, and 'a fair chunk of my own imagination'.[25] Wight anonymised the majority of his characters by renaming them: Notably, he gave the pseudonyms Siegfried and Tristan Farnon, respectively, to Donald Sinclair and his brother Brian, and used the name Helen Alderson for his wife Joan.

When Wight's first book was published, Brian Sinclair "was delighted to be captured as Tristan and remained enthusiastic about all Wight's books."[21] Donald Sinclair was offended by his portrayal and said, "Alfred, this book is a real test of our friendship." (He never called Wight 'Alf', mirrored in the books by Siegfried's always referring to Herriot as 'James' rather than 'Jim'.) Things calmed down and the pair continued to work together until they retired.

Wight's son wrote in The Real James Herriot that Donald Sinclair's character in the novels was considerably toned down, and in an interview described him as 'hilarious', 'a genius', and 'chaotic'.[26] The New York Times also stated that Donald Sinclair had far more rough edges than the Siegfried character. "Sinclair’s real-life behaviour was much more eccentric. (He once discharged a shotgun during a dinner party to let his guests know it was time to leave.)"[1] When he asked a vet who knew Sinclair if he was eccentric, actor Samuel West (who researched the vet for his role in the Channel 5 TV series) was told, "Oh, no ... he was mad."[27] The books are novels and most sources agree that about 50 per cent of the content was fiction.[9]

In a BBC interview taped in 1976, Wight recalled his life in Yorkshire, his career, and the success of his books.[28][29]

Film and television adaptations

[edit]

Wight's books have been adapted for film and television, including the 1975 film All Creatures Great and Small, followed by It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet in 1976.

The BBC produced a television series based on Wight's books titled All Creatures Great and Small, which ran from 1978 to 1980 and 1988–1990; ninety episodes were broadcast altogether.[30] Wight was often present on set and hosted gatherings for the cast and crew. "After filming we used to go for wonderful evenings in the Wensleydale Heifer with Tim Hardy and Chris Timothy," said Sandy Byrne, wife of the writer of the television series, Johnny Byrne. "Alf and Joan would come along. It was always immensely exciting. We made very good friends with Alf and Joan. We saw them several times over the years. Alf was still practising then, so his car would be packed with dogs. Joan was a very easy, down-to-earth person, I liked her very much. We also got to know their children, Jim and Rosie, very well."[31]

In September 2010, the Gala Theatre in Durham presented the world premier professional stage adaptation of All Creatures Great and Small.[32]

In 2010, the BBC commissioned the three-part drama Young James Herriot, inspired by Wight's early life and studies in Scotland. The series drew on archives and the diaries and case notes which Wight kept during his student days in Glasgow, as well as the biography written by his son.[33] The first episode was shown on BBC One on 18 December 2011, and drew six million viewers. The BBC announced in April 2012 that the series would not return.[34] A book titled Young James Herriot was written by historian and author John Lewis-Stempel to accompany the series.[35]

A new production of All Creatures Great and Small was produced by Playground Entertainment for Channel 5 in the United Kingdom, and PBS in the United States.[36] The production received some funding from Screen Yorkshire.[37] Most of the filming was completed in the Yorkshire Dales, including many exteriors in Grassington as the setting for the fictional town of Darrowby.[38] The first series, of six episodes and a special Christmas episode, premiered in the UK on Channel 5 on 1 September 2020 and in the US on PBS as part of Masterpiece on 10 January 2021. All Creatures Great and Small has now run four series, also of six episodes plus a Christmas special, and a fifth series has been approved as of November 2023.[39]

Recognition and tourist industry

[edit]

Thirsk has become a magnet for fans of Wight's books.[40] Following his death, the practice at 23 Kirkgate was restored and converted into a museum, The World of James Herriot, which focuses on his life and writings. A local pub renamed itself the "Darrowby Inn", after the village name that Wight created to represent the locale in which he practised. (By 2020, the pub had been renamed The Red Bear.)[41]

Portions of the surgery sets used in the All Creatures Great and Small BBC series are on display at the museum, including the living room and dispensary. Some of the original contents of the surgery can be found at the Yorkshire Museum of Farming in Murton, York.[42]

Grand Central rail company operates train services from Sunderland to London King's Cross, stopping at Thirsk. Class 180 DMU No. 180112 was named 'James Herriot' in Wight's honour, and was dedicated on 29 July 2009 by his daughter Rosemary and son James.[43] Actor Christopher Timothy, who played Herriot in the BBC television series, unveiled a statue of Wight in October 2014 at Thirsk Racecourse.[44]

Wight received an honorary doctorate from Heriot-Watt University in 1979, and was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1979 New Year Honours.[45][46] In 1994, the library at Glasgow Veterinary College was named the 'James Herriot Library' in honour of Wight's achievements. Wight was deeply gratified by this recognition, replying in his acceptance letter, "I regard this as the greatest honour that has ever been bestowed upon me."[8]: 351–352 He was a lifelong supporter of Sunderland A.F.C., and was made an honorary president of the club in 1991.[8]: 342

A blue plaque was placed at Wight's childhood home in Glasgow in October 2018.[47] There is also a blue plaque at 23 Kirkgate, Wight's former surgery.[48] Another blue plaque was unveiled by his children at his Brandling Street birthplace in Sunderland in September 2021.[49]

Minor planet 4124 Herriot is named in his honour.[50]

Published works

[edit]The original UK series

[edit]- If Only They Could Talk (1970) ISBN 0-330-23783-7

- It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet (1972) ISBN 0-330-23782-9

- Let Sleeping Vets Lie (1973) (including a few chapters that were not included in the omnibus editions All Creatures Great and Small and All Things Bright and Beautiful) ISBN 978-0-7181-1115-1

- Vet in Harness (1974) ISBN 0-330-24663-1

- Vets Might Fly (1976) ISBN 0-330-25221-6

- Vet in a Spin (1977) ISBN 0-330-25532-0

- The Lord God Made Them All (1981) ISBN 0-7181-2026-4

- Every Living Thing (1992) ISBN 0-7181-3637-3

Collected works from the original UK series

[edit]In the United States, Wight's first six books were considered too short to publish independently, so they were combined in pairs to form three omnibus volumes.

- All Creatures Great and Small (1972) (incorporating If Only They Could Talk, It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet, and three chapters from Let Sleeping Vets Lie) ISBN 0-330-25049-3

- All Things Bright and Beautiful (1974) (incorporating the majority of the chapters from Let Sleeping Vets Lie and Vet in Harness) ISBN 0-330-25580-0

- All Things Wise and Wonderful (1977) (incorporating Vets Might Fly and Vet in a Spin) ISBN 0-7181-1685-2

- The Lord God Made Them All (1981) ISBN 978-0312498344

- The Best of James Herriot (First Edition: 1982) ISBN 9780312077167; (Complete Edition: 1998) ISBN 9780312192365

- James Herriot's Dog Stories (1986) ISBN 0-3124-3968-7

- James Herriot's Cat Stories (1994) ISBN 0-7181-3852-X

- James Herriot's Yorkshire Stories (1998) ISBN 978-0718143848

- James Herriot's Animal Stories (2015) ISBN 9781250059352

Books for children

[edit]- Moses the Kitten (1984) ISBN 0-312-54905-9

- Only One Woof (1985) ISBN 0-312-09129-X

- The Christmas Day Kitten (1986) ISBN 0-312-13407-X

- Bonny's Big Day (1987) ISBN 0-312-01000-1

- Blossom Comes Home (1988) ISBN 0-7181-3060-X

- The Market Square Dog (1989) ISBN 0-312-03397-4

- Oscar, Cat-About-Town (1990) ISBN 0-312-05137-9

- Smudge, the Little Lost Lamb (1991) ISBN 0-312-06404-7

- James Herriot's Treasury for Children (1992) ISBN 0-312-08512-5

Other books

[edit]- James Herriot's Yorkshire (1979) ISBN 0-7181-1753-0

- James Herriot's Yorkshire Revisited (1999) ISBN 978-0312206291

Further reading

[edit]- Lord, Graham. James Herriot: The Life of a Country Vet (1997) ISBN 0-7472-1975-3

- Wight, Jim. The Real James Herriot: The Authorized Biography (1999) ISBN 0-7181-4290-X

- Lewis-Stempel, John. Young Herriot: The Early Life and Times of James Herriot (2011) ISBN 1-84990-271-2

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Vineyard, Jennifer (1 March 2021). "All Creatures Great and Small: Who was the real James Herriot". Irish Times/New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "The Yorkshire Vet". channel5.com. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "James Herriot Biography". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ Pringle, Michael (12 February 2018). "All Creatures Great and Small star Christopher Timothy reveals Scottish accent was banned on hit show". Daily Record. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "James Herriot". Thirsk Tourist Information. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Herriot, James (15 October 1990). James Herriot's Dog Stories. St. Martin's Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 0-312-92558-1.

- ^ Wight, Jim (27 April 2011). The Real James Herriot: A Memoir of My Father. New York: Random House. p. 126. ISBN 9780345434906.

- ^ a b c d e f Wight, Jim. 2000. The real James Herriot: A memoir of my father. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-42151-7

- ^ a b Lord, Graham (22 November 2012). James Herriot: The Life of a Country Vet. Headline. ISBN 9780755364701. Retrieved 3 March 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wight, James (27 April 2011). The Real James Herriot: A Memoir of My Father. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307790927. Retrieved 3 March 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Obituaries: James Herriot; Veterinarian, Author of Popular Memoirs". Los Angeles Times. 24 February 1995. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Obituary". jamesherriot.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "WIGHT, JAMES ALFRED of Mire Beck, Thirlby, Thirsk, North Yorkshire" in Probate Index for 1995 at probatesearch.service.gov.uk, accessed 5 August 2019

- ^ Honan, William H. (19 July 1999). "Joan Wight, Wife and Model for Author Herriot". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Nonfiction Book Review: The Real James Herriot: A Memoir of My Father by Jim Wight". Publishers Weekly.

- ^ "Veterinarian-author James Herriot dies". UPI. 23 February 1995. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ "James Herriot Dies at 78; Wrote 'All Creatures Great and Small'". The Buffalo News. 24 February 1995. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Lord, Graham (1998). James Herriot: the life of a country vet. Thorndike Press. ISBN 0-7862-1387-6. Retrieved 3 June 2020.: 97, 163

- ^ "University of Glasgow :: Story :: Biography of James Alfred Wight". www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Who is James Herriot and How "True" is All Creatures Great and Small?". Thirteen Media. 10 January 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Silverman, Al (2016). The Time of Their Lives: The Golden Age of Great American Book Publishers, Their Editors, and Authors (Kindle ed.). Open Road Integrated Media. p. 128.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (29 November 2020). "Michael Brooks obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "James Herriot Portrait of a Bestseller". YouTube. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Herriot, James. James Herriot's Yorkshire. St. Martin's Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-312-43970-9.

- ^ Van Maren, Jonathon (13 June 2017). "Remembering a bygone era: A conversation with James Herriot's son". The Bridgehead. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Kidd, Patrick (30 September 2020). "The madness of Siegfried". The Times. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ James Herriot Portrait of a Bestseller

- ^ "All Creatures Great and Small - James Herriot: Portrait of a Bestseller". www.thetvdb.com. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Newton, Grace (27 June 2019). "Much-loved James Herriot drama All Creatures Great and Small to return for new TV series". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ All Memories Great & Small, Oliver Crocker (2016; MIWK) ISBN 9781908630322

- ^ Burbridge, Steve (16 October 2010). "Theatre review: All Creatures Great and Small at Gala Theatre, Durham". British Theatre Guide. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "BBC One and drama announce two exciting new commissions for Scotland". BBC Press Office. 26 July 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Conlan, Tara (24 April 2012). "BBC axes Young James Herriot drama series". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Lewis-Stempel, John. "Young James Herriot". Penguin Books. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (27 June 2019). "Channel 5 to revive TV drama All Creatures Great and Small". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "Coming to Masterpiece: All Creatures Great and Small". Masterpiece, PBS. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Filming of All Creatures Great & Small". Get Out and About. 13 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

Grassington was this weekend transformed into 1930s England

- ^ "All Creatures Great and Small season 2 release date: cast, plot, and latest news". Radio Times. 23 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

Hopefully, that means it'll air on Channel 5 in the UK towards the end of 2021.

- ^ "It shouldn't happen to a vet". The Economist. 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Thirsk Pubs Town Village Country Inns Darrowby Three Tuns Dog Gun Black Swan Bull Bear Arms". www.thirsk.org.uk. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Our Museum". Murton Park. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Douglas, Andrew (29 July 2009). "Grand Central Railways honour James Herriot". The Northern Echo. Newsquest Media Group. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ White, Andrew (5 October 2014). "Actor Christopher Timothy unveils statue to James Herriot vet Alf Wight". The Northern Echo.

- ^ "Heriot-Watt University Honorary Graduates" (PDF). Heriot-Watt University. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Obituaries: James Herriot; Veterinarian, Author of Popular Memoirs". Los Angeles Times. 24 February 1995. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Plaque unveiled for famous vet and author at Yoker flat". Clydebank Post. 10 October 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Thirsk and Sowerby Blue Plaques Trail". Thirsk Town Council. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Gillan, Tony (13 September 2021). "Blue plaque finally unveiled at James Herriot's Sunderland birthplace in Roker". Sunderland Echo. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "IAU Minor Planet Center". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1916 births

- 1995 deaths

- People from Sunderland

- Writers from Tyne and Wear

- People educated at Hillhead High School

- Fellows of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Deaths from prostate cancer in England

- British autobiographers

- British children's writers

- British humorists

- British veterinarians

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- Royal Air Force personnel of World War II

- 20th-century British novelists

- British male novelists

- People from Thirsk

- Writers about Yorkshire

- Royal Air Force airmen

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers