Kurangaituku

| Folklore | Māori mythology |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) |

|

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Bay of Plenty |

| Details | Part-human, part-woman supernatural being |

Kurangaituku is a part-woman part-bird supernatural being in Māori mythology as told by the iwi (tribes) of Te Arawa and Raukawa. Her name is sometimes spelled Kurungaituku.[1][2][3] She is sometimes described as an ogress or a witch, although some versions of the legend are sympathetic to her and present her as a nurturing caretaker of birds. She is said to have been betrayed and defeated by the young Te Arawa man Hatupatu.

A number of New Zealand places are associated with Kurangaituku and Hatupatu, including Te Kōhatu o Hatapatu, a rock that Hatupatu is said to have hid in while escaping from her. She is also the subject of whakairo (traditional carving) and other artworks, and the Kurangaituku Netball Tournament has been held annually in Rotorua since 1933. Whiti Hereaka's novel Kurangaituku (2021) retells the legend from Kurangaituku's perspective, and won the top fiction prize at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Legend

[edit]Origins

[edit]The story of Kurangaituku is told in the oral traditions of the people of Te Arawa and Raukawa.[4][5] Her name is sometimes translated as "Kura of the claws".[6][7][8] In the telling by Te Arawa people, Kurangaituku is the antagonist to Hatupatu, the Te Arawa man who betrays and defeats her.[9]

Other versions of the tale are more sympathetic to Kurangaituku, including versions told by the Raukawa people.[5][2] Contemporary writers Ngahuia Te Awekotuku and Whiti Hereaka have both retold versions of the story from Kurangaituku's perspective.[10][11][9] Te Awekotuku's tale focuses on Kurangaituku's creative and nurturing nature, including through providing her home as a refuge for birds and other creatures.[10][12]

Capture of Hatupatu

[edit]

Hatupatu was the youngest of a family of brothers said to have arrived in New Zealand on the ancestral waka (canoe) of Arawa, and who lived on Mokoia Island in the centre of Lake Rotorua.[13]

In some versions of the tale, the young Hatupatu is hunting for birds in the forest when he encounters Kurangaituku, described as having wings on her arms, claws instead of fingers and a beak instead of a human mouth. She is sometimes described as an ogress or a witch. He runs away from her but is caught and taken to her cave, where he is imprisoned along with other pet birds and lizards.[14][6][15][8][16][17][12] It is sometimes said that they lived together as husband and wife.[18][19]

Nigel Te Hiko, a kaumātua and historian of the Raukawa people, considered that from a Raukawa perspective, Hatupatu was illegally hunting on Raukawa territory.[5] The Raukawa version of the tale says that Kurangaituku found Hatupatu injured and nursed him back to health.[5][2]

Betrayal

[edit]One day while Kurangaituku is out hunting, Hatupatu uses her taiaha (traditional weapon) to destroy her pet lizards and birds and steals her treasured korowai (feather cloaks).[14][10][11] In a 1927 version told by Enid Tapsell in the Auckland Star, Hatupatu and Kurangaituku decide to live together but he then decides to kill her birds and escape after "wearying" of her.[19] In a 1966 version published by Harry Dansey in bilingual magazine Te Ao Hou / The New World, Hatupatu was described as the slave of Kurangaituku who had intentionally killed her pet birds out of mischief.[20] In 1855 Richard Taylor recorded another version of the legend in which Hatupatu does not kill her birds but seals up the house to prevent them from escaping.[18][21]

One of the birds (which a number of versions of the tale describe as a riroriro)[13][6][22][17] is able to escape and tell Kurangaituku, who returns and chases Hatupatu through the forest. He is able to hide in a rock through a magical opening at one point during the chase, by calling for the rock to let him in.[14][4][18] When Hatupatu reaches Whakarewarewa, he is able to dodge around the boiling mud pools; Kurangaituku goes through them and is burned to death.[14][13][23]

Hine-ingoingo

[edit]Kurangaituku is also sometimes known as Hine-ingoingo.[4] Elsdon Best, in Maori Religion and Mythology Part 2 (published posthumously in 1982), related a version of the tale he had collected in which Hatupatu meets Hine-ingoingo and does not realise she is a turehu (supernatural being). In this version they live together for a time but Hatupatu still decides to escape and destroys her pet reptiles and birds. In this story it is the miromiro bird that alerts Hine-ingoingo to his betrayal, and after Hatupatu hides in the rock Hine-ingoingo is able to call it open, after which she embraces him and is saddened by his unkind treatment of her.[18] Best comments that Hatupatu "seems to have made but a poor return for the kindness displayed towards him by Hine-ingoingo, and he also appears to have left her to do all work in the collecting of food supplies."[18]

New Zealand places linked to Kurangaituku

[edit]Hatupatu and his family are said to have lived on Mokoia Island, an island located in Lake Rotorua.[15][13] In 1925 James Cowan, a Pākehā writer, described a tōtara tree and a tawa tree on Mokoia Island which were both called "Te Parē-a-Hatupatu" (Hatupatu's head-wreath), both said to have grown from twigs in a wreath worn by Hatupatu.[6]

Te Kōhatu o Hatapatu is a stone beside State Highway 1 at Ātiamuri, where Hatapatu is said to have hidden while hiding from Kurangaituku.[24] George Grey recorded visiting the rock in his notebook in 1866.[25] In 1935 it was referred to as Kurangaituku's Rock in an article in the Auckland Star.[8] It is said that Kurangaituku's clawmarks are visible on the rock,[6] and some people leave offerings such as sweets.[26] In 1980 Hone Tuwhare translated a version of the legend from the Māori language, and his notes (held by the Alexander Turnbull Library) record that he and his family used to stop at this rock and leave coins. However, after Tūwhare's work translating the legend, they "don't stop there anymore"; Tūwhare's notes explain that he doesn't "think the bastard [Hataputu] was worth it".[27] In 2017 work was undertaken by Waka Kotahi and other agencies to improve access to the rock and install informational placards. It was noted that the site was the only registered wāhi tapu (sacred place) in the south Waikato district.[28][29] In late 2020 the rock was damaged by a vandal with a sledgehammer.[30]

The pool of boiling mud into which Kurangaituku is said to have fallen at Whakarewarewa is called Whangapipiro.[31][32]

Artistic depictions

[edit]

Kurangaituku is depicted in a number of New Zealand artworks. Master whakairo carver Tene Waitere carved panels of Hatupatu and Kurangaituku in 1904–5.[13] In 1963 artist Fred O'Neill created a short film retelling the legend using Plasticine puppets.[33] In 2000 Kurangaituku featured on the 80c stamp in a special New Zealand Post stamp issue themed around Māori myths and legends.[34] A number of contemporary artist Lisa Reihana's works are inspired by Kurangaituku; for example in 2001 she made a photographic print representing Kurangaituku which is held by the Auckland Art Gallery.[11][35] Weaver Donna Campbell created an outfit entitled "Kurungaituku Vixen" in 2008, which is held in the Puke Ariki collection.[36]

Notably, she features in a number of public artworks around the city of Rotorua. Rotorua artists Glenys Courtney-Strachan and Maria Marshall have painted several murals featuring Kurangaituku, including for a kindergarten in 2017 and for the Rotorua Library in 2018.[37][38] Since the 1990s Rotorua's Travel Centre has featured a mixed media collaborative artwork depicting Kurangaituku designed by Ata Armstrong and created by local women.[12] In 2006 a whakairo carving of Kurangaituku by Clive Fugill was installed to welcome visitors at the entrance of the Māori Arts and Crafts Institute as part of a redevelopment of the institute.[39]

The novel Kurangaituku by Whiti Hereaka, published in 2021 by Huia Publishers, is told from Kurangaituku's perspective and in a way reflecting Māori oral traditions.[9] When Hereaka was growing up her family often stopped at Te Kōhatu o Hatapatu, the stone at Ātiamuri, on their way to Rotorua.[40] In a review for The Pantograph Punch, Ariana Tikao notes that the structure "is much like Māori oratory – not linear, but existing in different times, cycles, and spaces all at once, then looping back on itself".[27] The work won the top prize for fiction at the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards in 2022.[40] Kurangaituku also features in Taniwha, Giants and Supernatural Creatures (2008), edited by Ross Calman,[41] and in Ngahuia Te Awekotuku's retelling in Pūrākau: Māori myths retold by Māori writers (2019).[10]

Other cultural references

[edit]The Kurangaituku Netball Tournament has been an annual event in Rotorua since 1933 (originally a basketball tournament).[42][43][44] The name originates from a 1 m (3 ft 3 in) tall trophy depicting Kurangaituku carved out of a totara tree by Pine Taiapa and used since the tournament began.[45]

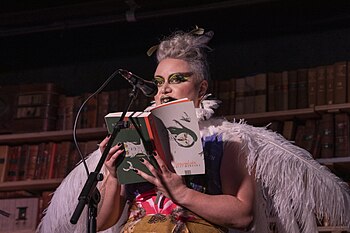

In 2015 the Rotorua Chamber of Pride, led by Tāmati Coffey, won "best float" at the Auckland Pride Parade for their float depicting Kurangaituku; a judge described it as "re-imagining her as a victim needing to be freed from her historical stigma".[46]

Tangaroa (2021), the second album of the band Alien Weaponry, features a song called "Hatupatu" based on the legend. The band's drummer, Henry de Jong, noted that the story is "stepping out of colonial history and going more to the word of mouth folklore aspect of Māori history and culture".[47] Wellington band DAHTM released their debut album titled Kurungaituku in 2021.[48]

Kurangaituku featured as a character on the first episode of season 4 of the television show Wellington Paranormal, which aired on 16 February 2022.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ "The tournament takes its name from the impressive 1m high wooden trophy". The Daily Post. 31 August 2006. p. A13. ProQuest 432087918.

There has been debate over the years about the spelling of Kurangaituku, with some Maori believing it should be Kurungaituku. But the organisers have been unable to verify it one way or another, so they are sticking to the spelling on the trophy.

- ^ a b c Te Hiko, Huirama; Te Hiko, Nigel (June 2017). "Kurungaituku, Guardian of the Forest" (PDF). Raukawa Settlement Trust. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Hatupatu me Kurungaituku - Hatupatu and the Birdwoman". Rotorua Daily Post. 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Inia, Raimona (10 December 2021). "Kāhu ki Rotorua: Hatupatu me Kurungaituku - Hatupatu and the Birdwoman". Rotorua Daily Post. Retrieved 2 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d Kerr, Florence (18 September 2020). "Coronavirus: The whānau that's endured the cruellest blow from Covid-19". Stuff. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Cowan, James (1925). "Chapter XI: The Story of Hatupatu and Kura-of-the-Claws". Fairy Folk Tales of the Maori. Auckland: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Hereaka, Whiti (15 May 2022). "An extract from Whiti Hereaka's Ockham Award winning book, Kurangaituku". Stuff. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Tangiwhai (24 January 1935). "Tapu". Auckland Star. p. 6. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Whiti Hereaka gives bird-woman Kurangaituku a voice". Radio New Zealand. 31 October 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia (2019). "Chapter 11: Ogresses". In Ihimaera, Witi; Hereaka, Whiti (eds.). Pūrākau: Māori myths retold by Māori writers. Auckland: Penguin Random House New Zealand. ISBN 9780143772972.

- ^ a b c "REIHANA, Lisa; Digital Marae". QAGOMA Collection Online. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Potiki, Brian (6 March 2020). "Collaborative artwork another step in art trail". The Daily Post. p. A12. ProQuest 2371129013.

- ^ a b c d e Tapsell, Paora (1 March 2017). "Story: Te Arawa – Hatupatu and Kurangaituku". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Hatupatu and Kurangaituku". Te Arawa Stories. Rotorua Library. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Hatupatu and Kurungaituku the Birdwoman" (PDF). Rotorua Museum. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "In Search of the North Island". Manawatu Times. 3 November 1937. p. 13. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b Keys, Ben (23 December 1922). "The Riroriro". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Best, Elsdon (1982). "The Story of Hatupatu and Hine-ingoingo, the Tahurangi". Maori Religion and Mythology Part 2. Wellington: P. D. Hasselberg.

- ^ a b Tapsell, Enid (5 November 1927). "Marvellous Hatupatu". Auckland Star. p. 21. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Dansey, Harry (March 1966). "Hatupatu and Kurangaituku: Another Version of the Story". Te Ao Hou / The New World. 54: 30–31. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Richard (1855). Te Ika a Maui, or, New Zealand and its Inhabitants. London: Wertheim and Macintosh. pp. 47–49. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Tiritiri Matangi: An education resource for schools: extra resources" (PDF). Department of Conservation. p. 223. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Tapsell, Paora (1 March 2017). "Story: Te Arawa – Settlement and migration". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ Keane, Basil (24 September 2007). "Story: Taniwha – Hatupatu's rock". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ "Sir George Grey's Notebook". The New Zealand Herald. 18 April 1903. p. 1 (supplement). Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Swarbrick, Nancy (11 June 2015). "Story: Waikato places – Roadside Stories: Hatupatu's Rock". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b Tikao, Ariana (14 March 2022). "Power of the Story: A Review of Kurangaituku". The Pantograph Punch. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "Rock entry complete". The Daily Post. 27 April 2017. p. A10. ProQuest 1892010883.

- ^ "Restoration of Hatupatu Rock complete". Waka Kotahi | New Zealand Transport Agency. 20 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Kerr, Florence (6 January 2021). "Sacred Hatu Patu rock smashed with a sledgehammer in a brazen attack". Stuff. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Cowan, James (18 June 2010). "Old Rotorua: Legends of the Lakes". The Evening Post. p. 10. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Bomford, J.H. (1 November 1938). "The Witch's Rock: A Maori Legend". The New Zealand Railways Magazine. 13 (8): 56. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Hatupatu and the Bird Woman - A Māori Legend". Ngā Taonga: Sound and Vision. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Stamps feature Maori supernatural". The Dominion. 17 February 2000. p. 10. ProQuest 315144992.

- ^ "Kurangaituku". Auckland Art Gallery. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Kakahu "Kurungaituku Vixen"". Puke Ariki Collection Online. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ James, Shauni (8 June 2018). "Vibrant mural helps captivate children with local stories". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Frank, Angela (25 August 2017). "Kurangaituku story in new mural". Rotorua Weekender. p. A11. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Watson, Mike (28 August 2006). "Arts centre revamp nears end". The Dominion Post. p. A7. ProQuest 338271888.

- ^ a b Gifford, Adam (12 May 2022). "Birdwoman Kurangaituku captures Ockham tohu". Waatea News: Māori Radio Station. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Book Review: Taniwha, Giants and Supernatural Creatures". The Daily Post. 12 August 2008. p. A9. ProQuest 432181897.

- ^ Ross, Sarah Cowley (6 July 2020). "Meet the super-volunteer who took a risk on Dame Noeline Taurua". Stuff. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Houghton, Caitlin (3 September 2019). "Kurangaituku Netball Tournament keeps on growing". Sunlive. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Kurangaituku Cup". Hawke's Bay Tribune. 12 September 1936. p. 11. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Kurangaituku stats". The Daily Post. 4 September 2008. p. A16. ProQuest 432190214.

- ^ Kinita, Dana (27 February 2015). "Kurangaituku proudly soars over Auckland parade rivals". The Rotorua Daily Post. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ Skipwith, David (9 September 2021). "Alien Weaponry's Europe audiences sing along in te reo". Stuff. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ Kean, Annabel (5 July 2021). "DAHTM Unleash Two Tracks From LP 'Kurungaituku'". Under the Radar. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Croot, James (16 February 2022). "Wellington Paranormal: TVNZ's hilarious police mockumentary set to go out on a high". Stuff. Retrieved 11 April 2023.