Mauveine

Mauveine, also known as aniline purple, was the first synthetic organic dye[1][2] . The chemical name is 3-amino-2,±9-dimethyl-5-phenyl-7-(p-tolylamino)phenazinium acetate. The formula is C26H23N4+X− (mauveine A) and C27H25N4+X− (mauveine B, see below).

It was discovered serendipitously in 1856 by an 18-year old, William Henry Perkin, who was trying to synthesize the anti-malaria drug quinine as a challenge offered by his professor, August Wilhelm von Hofmann. In one of his attempts related to the quinine challenge, Perkin oxidized aniline using potassium dichromate. Under these conditions, the aniline reacted with toluidine impurities in it to produce a black solid, a fairly common result in "failed" organic syntheses. However, while trying to clean out his flask, Perkin discovered that some component of the black solid dissolved in alcohol to give a purple-colored solution, which proved to be an effective dye for silk and other textiles.

Perkin patented the new dye and the next year, he opened a dyeworks at Greenford on the banks[3] of the Grand Union Canal in London in order to mass produce it. Mauve became highly fashionable in 1862 when Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom appeared at the Royal Exhibition in a mauve silk gown. Mauve fell out of fashion in the late 1860s to newer synthetic colors, but not before making Perkin's fortune and birthing the synthetic chemical industry. Later work on chemical dyes also led to the (accidental) development of modern chemotherapy (see Sulfonamide).

This color of this dye may be familiar from its widespread use in spirit duplicator (trade name Ditto) printing machines.

Chemical analysis

A modern-day laboratory procedure for the organic synthesis of mauveine consists of dissolving a mixture of aniline, p-toluidine and o-toluidine in sulfuric acid and water (large excess poor solubility) in roughly a 1:1:2 ratio followed by addition of potassium dichromate [4]. The actual molecular structure of mauveine proved quite difficult to determine and was not known with certainty until 1994.[5]

-

skeletal formula of mauveine A -

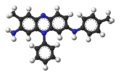

ball-and-stick model of mauveine A -

skeletal formula of mauveine B -

ball-and-stick model of mauveine B

It is actually a (variable) mixture of two related aromatic compounds, the main component mauveine A, shown above at right, and a minor component mauveine B, which has one additional methyl group. A is built up from 2 molecules of aniline, one of p-toluidine and one of o-toluidine whereas B incorporates aniline, p-toluidine and o-toluidine one molecule each. As Perkin showed in 1879,[6] mauveine B is related to the safranines by oxidative/reductive loss of the p-tolyl group. In fact, safranine itself is a 2,8-dimethyl phenazinium salt, whereas the parasafranine produced by Perkin must be presumed[7] to be the 1,8-(or 2,9) dimethyl isomer.

In 2007 two other mauveine components were identified called mauveine C (an additional p-methyl group on mauveine A) and mauveine B2 (an isomer of mauveine B with methyl on different aryl group) [8]

InChI identifiers

- The InChI identifier for mauveine B is InChI=1/C27H24N4/c1-17-9-11-20(12-10-17)29-21-13-19(3)27-26(15-21)31(22-7-5-4-6-8-22)25-16-23(28)18(2)14-24(25)30-27/h4-16H,1-3H3,(H2,28,29)/p+1

- The InChI identifier for mauveine A is InChI=1/C26H22N4/c1-17-8-10-19(11-9-17)28-20-12-13-23-25(15-20)30(21-6-4-3-5-7-21)26-16-22(27)18(2)14-24(26)29-23/h3-16H,1-2H3,(H2,27,28)/p+1

- The InChI identifier for safranine is InChI=1/C20H18N4/c1-12-8-17-19(10-15(12)21)24(14-6-4-3-5-7-14)20-11-16(22)13(2)9-18(20)23-17/h3-11H,1-2H3,(H3,21,22)/p+1

- The InChI identifier for parasafranine is InChI=1/C20H18N4/c1-12-9-17-18(11-16(12)22)24(15-6-4-3-5-7-15)19-10-14(21)8-13(2)20(19)23-17/h3-11H,1-2H3,(H3,21,22)/p+1

External links

- Perkin anniversary website

- Rotatable 3D models of mauveine are available using Jmol

References

- ^ Hubner K (2006). "History - 150 Years of mauveine". Chemie in unserer Zeit. 40 (4): 274–275. doi:10.1002/ciuz.200690054.

- ^ Anthony S. Travis (1990). "Perkin's Mauve: Ancestor of the Organic Chemical Industry". Technology and Culture. 31 (1): 51–82.

- ^ Google Earth location: Download

- ^ A Microscale Synthesis of Mauve Scaccia, Rhonda L.; Coughlin, David; Ball, David W. J. Chem. Educ. 1998 75 769 Abstract

- ^ O. Meth-Cohn, M. Smith, "What did W. H. Perkin actually make when he oxidised aniline to obtain mauveine?", J. Chem. Soc. Perkin 1, 1994, 5-7. DOI: 10.1039/P19940000005. This reference is not Open Access.

- ^ W. H. Perkin, "On mauveine and allied colouring matters", J. Chem. Soc. Trans., 1879, 717-732. DOI: 10.1039/CT8793500717.

- ^ Website source: ch.ic.ac.uk Link

- ^ Revisiting Perkin's dye(s): the spectroscopy and photophysics of two new mauveine compounds (B2 and C) J. Seixas de Melo, S. Takato, M. Sousa, M. J. Melo and A. J. Parola Chem. Commun., 2007, 2624 - 2626, doi:10.1039/b618926a