Mythological anecdotes of Ganesha

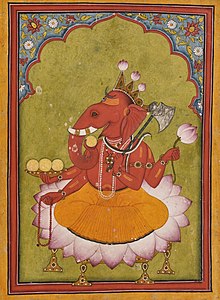

There are many anecdotes of Ganesha. Ganesha's elephant head makes him easy to identify.[1] He is worshipped as the lord of beginnings and as the lord of removing obstacles,[2] the patron of arts and sciences, and the god of intellect and wisdom.[3] In his survey of Ganesha's rise to prominence in Sanskrit literature, Ludo Rocher notes that:

Above all, one cannot help being struck by the fact that the numerous stories surrounding Gaṇeśa concentrate on an unexpectedly limited number of incidents. These incidents are mainly three: his birth and parenthood, his elephant head, and his single tusk. Other incidents are touched on in the texts, but to a far lesser extent.[4]

History about the birth of Ganesha are found in the later Puranas, composed from about 600 CE onwards. References to Ganesha in the earlier Puranas, such as the Vayu and Brahmanda Puranas are considered to be later interpolations made during the 7th to 10th centuries.[5]

Birth and childhood

While Ganesha is popularly considered to be the son of Shiva and Parvati, the Puranic myths relate several different versions of his birth.[6][7] These include versions in which he is created by Shiva,[8] by Parvati,[9] by Shiva and Parvati,[10] or in a mysterious manner that is later discovered by Shiva and Parvati.[11]

The family includes his brother Kartikeya.[12] Regional differences dictate the order of their births. In North India, Skanda is generally said to be the elder brother while in the South, Ganesha is considered the first born.[13] Prior to the emergence of Ganesha, Skanda had a long and glorious history as an important martial deity from about 500 BCE to about 600 CE, when his worship declined significantly in North India. The period of this decline is concurrent with the rise of Ganesha. Several stories relate episodes of sibling rivalry between Ganesha and Skanda[14] and may reflect historical tensions between the respective sects.[15]

Once there was a competition between Ganesha and his brother to see who could circumambulate the three worlds faster and hence win the fruit of knowledge. Skanda went off on a journey to cover the three worlds while Ganesha simply circumambulated his parents. When asked why he did so, he answered that his parents Shiva and Parvati constituted the three worlds and was thus given the fruit of knowledge.

Elephant head

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Hindu mythology presents many stories, which explain how Ganesha obtained his elephant or gaja head. Often, the origin of this particular attribute is to be found in the same anecdotes which tell about his birth. The stories also reveal the origins of the enormous popularity of his cult. Devotees sometimes interpret his elephant head as indicating intelligence, discriminative power, fidelity, or other attributes thought to be had by elephants. The large elephant ears are said to denote wisdom and the ability to listen to people who seek help.

Decapitation by Shiva

The most well-known story is probably the one taken from the Shiva Purana. The goddess Parvati had started preparing for a bath. As she did not want to be disturbed during her bath and since Nandi was not at Kailash to keep guard of the door, Parvati took the turmeric paste (for bathing) from her body and made a statue of a boy, breathing life into him. This boy was instructed by Parvati to guard the door and to not let anyone in until she had finished her bath.

After Shiva had come out of his meditation, he wished to meet Parvati, but found himself being halted by a strange boy. Shiva tried to reason with the boy, saying that he was Parvati's husband, but the boy did not listen and was determined to keep Shiva at bay. The boy's behaviour surprised Shiva. Sensing that this was no ordinary boy, the usually even tempered Shiva decided he would have to fight the boy and in his divine fury, severed the boy's head with his trishul, killing him instantly.

When Parvati heard word of this, she was so enraged that she decided to destroy all of creation. At her call, several ferocious multi-armed forms, the yoginis, arose from her body and threatened annihilation. Lord Brahma, being the creator, naturally had his concerns, and pleaded that she reconsider her drastic plan. She acquiesced with two conditions: one, that the boy be brought back to life, and two, that he be forever revered before all the other gods in prayer.

Shiva, having cooled down by this point, agreed to Parvati’s conditions. He sent his devotees out with orders to bring back the head of the first creature that lay with its head facing the north. They soon returned with the head of a strong and powerful elephant named Gajasura, which Lord Brahma placed atop the boy's body. Breathing new life into him, he was declared as the Gajanana and offered him the status of being the foremost among the gods in prayer, and the title of the leader of all the ganas (classes of beings), Ganapati.

Shiva and Gajasura

Once, there existed an Asura (demon) with all the characteristics of an elephant, called Gajasura, who was undergoing a penitence (tapas). Shiva, satisfied by this austerity, decided to grant him, as a reward, whatever gift he desired. The demon wished that he could emanate fire continually from his own body so that no one could ever dare to approach him. The Lord granted him his request. Gajasura continued his penitence and Shiva, who appeared in front of him from time to time, asked him once again what he desired. The demon responded: "I desire that You inhabit my stomach." Shiva agreed.

Parvati sought him everywhere without results. As a last recourse, she went to her brother Vishnu, asking him to find her husband. He, who knows everything, reassured her: "Don't worry, dear sister, your husband is Bhola Shankara and promptly grants to his devotees whatever they ask of him, without regard for the consequences; for this reason, I think he has gotten himself into some trouble. I will find out what has happened."

Then Vishnu, the omniscient director of the cosmic game, staged a small comedy. He transformed Nandi (the bull of Shiva) into a dancing bull and conducted him in front of Gajasura, assuming, at the same time, the appearance of a flutist. The enchanting performance of the bull sent the demon into ecstasies, and he asked the flutist to tell him what he desired. The musical Vishnu responded: "Can you give me that which I ask?" Gajasura replied: "Who do you take me for? I can immediately give you whatever you ask." The flutist then said: "If that's so, liberate Shiva from your stomach." Gajasura understood then that this must have been no other than Vishnu himself, the only one who could have known that secret and he threw himself at his feet. Having agreed to liberate Shiva, Gajasura asks him for two last gifts: "I have been blessed by you with many gifts; my last requests are that everyone should remember me adoring my head and you should wear my skin."

Gaze of Shani

A lesser known story from the Brahma Vaivarta Purana narrates a different version of Ganesha's birth. On the insistence of Shiva, Parvati fasted for years (punyaka vrata) to propitiate Vishnu so that he would grant her a son. Vishnu, after the completion of the sacrifice, announced that he would incarnate himself as her son in every kalpa (eon). Accordingly, Ganesha was born to Parvati as a charming infant. This event was celebrated with great enthusiasm and all the gods were invited to take a look at the baby. However Shani (Saturn), the son of Surya, hesitated to look at the baby since Shani was cursed with the gaze of destruction. Shani came to a decision and looked at the goddess Parvati's baby from the edge of his left eye.[17] However Parvati insisted that he look at the baby, which Shani did, and immediately the infant's head fell off. Seeing Shiva and Parvati grief-stricken, Vishnu mounted on Garuda, his divine eagle, and rushed to the banks of the Pushpa-Bhadra river, from where he brought back the head of a young elephant. The head of the elephant was joined with the headless body of Parvati's son, thus reviving him. The infant was named Ganesha and all the Gods blessed Ganesha and wished Him power and prosperity.[18]

Other versions

Another tale of Ganesha's birth relates to an incident in which Shiva slew Aditya(Lord sun), the son of a sage. Shiva restored life to the dead boy, but this could not pacify the outraged sage Kashyapa, who was one of the seven great Rishis. Kashyap cursed Shiva and declared that Shiva's son would lose his head. When this happened, the head of Indra's elephant was used to replace it.

Still another tale states that on one occasion, Parvati's used bath-water was thrown into the Ganges, and this water was drunk by the elephant-headed Goddess Malini, who gave birth to a baby with four arms and five elephant heads. The river goddess Ganga claimed him as her son, but Shiva declared him to be Parvati's son, reduced his five heads to one and enthroned him as the controller of obstacles (Vignesha).[19]

Broken tusk

There are various anecdotes which explain how Ganesha broke off one of his tusks. Devotees sometimes say that his single tusk indicates his ability to overcome all forms of dualism. In India, an elephant with one tusk is sometimes called a "Ganesh".

Ganesha the scribe

In the first part of the epic poem Mahabharata, it is written that the sage Vyasa (Vyāsa) asked Ganesha to transcribe the poem as he dictated it to him. Ganesha agreed, but only on the condition that Vyasa recite the poem uninterrupted, without pausing. The sage, in his turn, posed the condition that Ganesha would not only have to write, but would have to understand everything that he heard before writing it down. In this way, Vyasa might recuperate a bit from his continuous talking by simply reciting a difficult verse which Ganesha could not understand. The dictation began, but in the rush of writing Ganesha's feather pen broke. He broke off a tusk and used it as a pen so that the transcription could proceed without interruption, permitting him to keep his word.

This is the single passage in which Ganesha appears in that epic. The story is not accepted as part of the original text by the editors of the critical edition of the Mahabharata,[20] where the twenty-line story is relegated to a footnote to an appendix.[21] Ganesha's association with mental agility and learning is probably one reason he is shown as scribe for Vyasa's dictation of the Mahabharata in this interpolation to the text.[22] Brown dates the story as 8th century CE, and Moriz Winternitz concludes that it was known as early as c. 900 CE but he maintains that it had not yet been added to the Mahabharata some 150 years later. Winternitz also drew attention to the fact that a distinctive feature of Southern manuscripts of the Mahabharata is their omission of this Ganesha legend.[23]

Ganesha and Parashurama

One day, Parashurama, an avatar of Vishnu, went to pay a visit to Shiva, but along the way he was blocked by Ganesha. Parashurama hurled himself at Ganesha with his axe and Ganesha (knowing that this axe was given to him by Shiva) allowed himself, out of respect for his father, to be struck and lost his tusk as a result.[24] By this lord Ganesha yells out of pain and goddess Parvati comes running out from the cave. She, looking at the condition of her son asks Kartikeya what happened. When she learns about Parashurama and that he was the reason for the axing off of one of the tusks of her beloved son lord Ganesha, she assumes the form of Goddess Kali and threatens to slay the sage for his actions. At that time, Parashurama remembers lord Krishna. Lord Vishnu goes to that place and disguised himself as a small brahmin boy. Later he tells lord Shiva that he had arrived to that place in order to sort out the matter between Parashurama and goddess Parvati. He preaches the Ganesha Naamaashtaka Stotra and asks Parashurama to please the supreme goddess Parvati by reciting holy hymns on her. Parashurama does the same, as a result of which goddess Parvati gets pacified and blesses the Parashurama.[25]

Ganesha and the Moon

After coming back from the feast at Kubera's palace, Ganapati was riding on his mouse Dinka on the way home. It was a full moon that night. As he was riding, Dinka saw a snake and ran behind a bush. Ganapati fell to the ground, and his stomach broke open. Ganapati started to put the food back in his stomach. The moon god Chandra saw him and started laughing loudly. Angered by this, Ganapati pronounced a curse on the moon god: "You shall be always black and never be seen by anyone." Frightened by the curse, the moon god started pleading for mercy. Ganapati said "Okay, but you shall be changing from new moon to full moon. Also if anyone sees the moon on my birthday, he or she shall not attain moksha (liberation)." The moon god kept quiet. After Ganapati had finished putting the food in his stomach, he took the snake and tied it around his belly. Then he continued back home.

Head of the celestial armies

There once took place a great competition between the Devas to decide who among them should be the head of the Gana (the troops of semi-gods at the service of Shiva). The competitors were required to circle the world as fast as possible and return to the Feet of Parvati. The gods took off, each on his or her own vehicle, and even Ganesha participated with enthusiasm in the race; but he was extremely heavy and was riding on Dinka, a mouse! Naturally, his pace was remarkably slow and this was a great disadvantage. He had not yet made much headway when there appeared before him the sage Narada (son of Brahma), who asked him where he was going. Ganesha was very annoyed and went into a rage because it was considered unlucky to encounter a solitary Brahmin just at the beginning of a voyage. Notwithstanding the fact that Narada was the greatest of Brahmins, son of Brahma himself, this was still a bad omen. Moreover, it wasn't considered a good sign to be asked where one was heading when one was already on the way to some destination; therefore, Ganesha felt doubly unfortunate. Nonetheless, the great Brahmin succeeded in calming his fury. Ganesha explained to him the motives for his sadness and his terrible desire to win. Narada consoled and exhorted him not to despair; he said that for a child, the whole world was embodied within the mother, so all Ganesha had to do was to circle his Parvati and he would defeat those who had more speed but less understanding.

Ganesha returned to his mother, who asked him how he was able to finish the race so quickly. Ganesha told him of his encounter with Narada and of the Brahmin's counsel. Parvati, satisfied with this response, pronounced her son the winner and, from that moment on, he was acclaimed with the name of Ganapati (conductor of the celestial armies)[26] and Vinayaka (lord of all beings).[27]

Appetite

One anecdote, taken from the Purana, narrates that the treasurer of Svarga (paradise) and god of wealth, Kubera, went one day to Mount Kailash in order to receive the darshan (vision) of Shiva. Since he was extremely vain, he invited Shiva to a feast in his fabulous city, Alakapuri, so that he could show off to him all of his wealth. Shiva smiled and said to him: "I cannot come, but you can invite my son Ganesha. But I warn you that he is a voracious eater." Unperturbed, Kubera felt confident that he could satisfy even the most insatiable appetite, like that of Ganesha, with his opulence. He took the little son of Shiva with him into his great city. There, he offered him a ceremonial bath and dressed him in sumptuous clothing. After these initial rites, the great banquet began. While the servants of Kubera were working themselves to the bone in order to bring the portions, the little Ganesha just continued to eat and eat and eat. His appetite did not decrease even after he had devoured the servings which were destined for the other guests. There was not even time to substitute one plate with another because Ganesha had already devoured everything, and with gestures of impatience, continued waiting for more food. Having devoured everything which had been prepared, Ganesha began eating the decorations, the tableware, the furniture, the chandelier. Terrified, Kubera prostrated himself in front of the little omnivorous one and supplicated him to spare him, at least, the rest of the palace.

"I am hungry. If you don't give me something else to eat, I will eat you as well!", he said to Kubera. Desperate, Kubera rushed to mount Kailasa to ask Shiva to remedy the situation. The Lord then gave him a handful of roasted rice, saying that something as simple as a handful of roasted rice would satiate Ganesha, if it were offered with humility and love. Ganesha had swallowed up almost the entire city when Kubera finally arrived and humbly gave him the rice. With that, Ganesha was finally satisfied and calmed.

References

- ^ Martin-Dubost, p. 2.

- ^ These ideas are so common that Courtright uses them in the title of his book, Gaṇeśa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings.

- ^ Heras, p. 58.

- ^ Brown, p. 73.

- ^ Krishan, p. 103.

- ^ For a summary of Puranic variants of birth stories, see Nagar, pp. 7-14.

- ^ Martin-Dubost, pp. 41-82.

- ^ Linga Purana.

- ^ Shiva Purana IV. 17.47-57 and Matsya Purana 154.547.

- ^ Varāha Purana 23.18-59.

- ^ Brahmavaivarta Purana, Ganesha Khanda, 10.8-37.

- ^ For a summary of variant names for Skanda, see Thapan, p. 300 and Brown, p. 355.

- ^ Khokar and Saraswati, p.4.

- ^ Brown, pp. 4, 79.

- ^ Gupta, p. 38.

- ^ Martin-Dubost, p. 64.

- ^ HS, ANUSHA (2020). Stories on lord Ganesh series -13: From various sources of Ganesh Purana. Independently published (March 27, 2020). pp. number 15. ISBN 979-8631217102.

- ^ Barratt, Barnaby (Dec 2009). "Ganesha's lessons for psychoanalysis: Notes on fathers and sons, sexuality and death". Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society. 4 (14): 317–336. doi:10.1057/pcs.2008.53. S2CID 144642792.

- ^ For the name Vighnesha, see Courtright pp. 156, 213.

- ^ Brown, pp. 71-72.

- ^ Mahābhārata, Vol. 1, Part 2. Critical edition, p. 884.

- ^ Brown, p. 4.

- ^ Winternitz, Moris. "Gaṇeśsa in the Mahābhārata". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1898:382).

Brown, p. 80. - ^ "Ganesha". IndianCultureOnline.com. Gurjari.net. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ^ HS, ANUSHA (2021). Stories on lord Ganesh series - 20: From various sources of Ganesh Purana. Independently published (April 6, 2020). pp. summary of 20 pages cited. ISBN 979-8634399676.

- ^ Apte, p. 395

- ^ Thapan, p. 20.

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4. (fourth revised & enlarged edition).

- Brown, Robert L. (1991). Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. Albany: State University of New York. ISBN 0-7914-0657-1.

- Courtright, Paul B. (1985). Gaṇeśa: Lord of Obstacles, Lord of Beginnings. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505742-2.

- Gupta, Shakti M. (1988). Karttikeya: The Son of Shiva. Bombay: Somaiya Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-7039-186-5.

- Heras, H. (1972). The Problem of Ganapati. Delhi: Indological Book House.

- Krishan, Yuvraj (1999). Gaņeśa: Unravelling An Enigma. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-1413-4.

- Martin-Dubost, Paul (1997). Gaņeśa: The Enchanter of the Three Worlds. Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies. ISBN 81-900184-3-4.

- Nagar, Shanti Lal (1992). The Cult of Vinayaka. New Delhi: Intellectual Publishing House. ISBN 81-7076-043-9.

- Saraswati, S.; Ashish Khokar (2005). Ganesha-Karttikeya. New Delhi: Rupa and Co. ISBN 81-291-0776-7.

- Thapan, Anita Raina (1997). Understanding Gaņapati: Insights into the Dynamics of a Cult. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers. ISBN 81-7304-195-4.