Petro Marko

Petro Marko | |

|---|---|

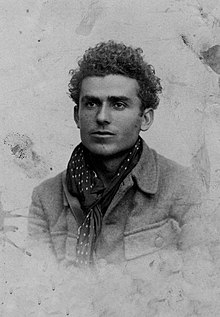

Marko in 1943 | |

| Born | November 25, 1913 Dhërmi, Albania |

| Died | December 27, 1991 (aged 78) Tirana, Albania |

| Occupation | writer |

| Notable works | Hasta La Vista (novel) Nata e Ustikës (English: Ustica night) |

| Spouse | Safolina Marko |

| Children | 2 (Jamarbër, Arianita) |

| Signature | |

Petro Marko (November 25, 1913 – December 27, 1991) was an Albanian writer. His best-known novel is titled Hasta La Vista and recounts his experiences as a volunteer of the Republican forces during the Spanish Civil War. Petro Marko is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Albanian prose.[1]

Life[edit]

Petro Marko was born in Dhërmi, southern Albania in 1913. He started writing at the age of twenty and his first works were published in journals of the time with support from Ernest Koliqi his mentor. His articles would be published in periodicals as Lirija, Shqipëria e Re, Bota e Re, and Koha e Re magazine since he was 20.[2] From March 1, 1936 he became the editor of ABC, a literary review which was banned by the monarchist authorities soon after,[3] following with Marko being arrested and sent to internment.[2] In August 1936 he joined the Garibaldi Battalion of the Republican forces of the Spanish Civil War along with other notable Albanians like Mehmet Shehu, Asim Vokshi, Emrush Myftari and Thimi Gogozoto.[4]

During the Spanish Civil War along with Skënder Luarasi, son of Petro Nini Luarasi he published in Madrid the Albanian newspaper Vullnëtari i Lirisë (English: Volunteer of Freedom), which was discontinued after two issues because of the military status of Madrid.[1] His best-known work Hasta La Vista published in Tirana in 1958 was largely influenced by his experiences during the Spanish Civil War. In 1940 after being repatriated from France to Albania he was arrested by the Italian army, imprisoned in Bari,[2] then and sent along with 600 other prisoners to Ustica, an island of the Tyrrhenian Sea from 1941 to 1943,[4] finishing with Regina Coeli prison near Rome in 1944.[2]

In October 1944 he joined the forces of the Albanian National Liberation Front as a partisan. After the war he became editor-in-chief of the periodical Bashkimi (English: Unity), but was arrested again in 1947 by Koçi Xoxe, Minister of Defense and was released after Xoxe's downfall in 1949.[1] Marko would be accused of giving information to Anglo-Americans during his time as editor-in-chief. His last prison time would be May 1947-May 1950.[2] Nevertheless, Marko remained an idealist and antifascist. In a letter sent to the Supreme Military Court of Albania from prison, he would state: Petro Marko is sentenced to three years and is thrown into the midst of those who he fought against, and hated. For me, this is the greatest injustice, it is a crime that takes place against me, because I am innocent and never ever, starting as early as 1932, did not bring any harm to the people.... Another of his letters sent to the Supreme Court, still while serving time in jail, he would mention that he had been tortured and forced to admit something, otherwise he would die.[2] His time in the communist prison would be described in his Interview with myself: Clouds and stones (Albanian: Intervistë me vetveten: Retë dhe gurët).[5] The same book would express his feelings about his Albanian identity, considering his origins in the controversial[why?] Bregu Region, sometimes called shortly as Himara.[6]

He died in 1991, while in 2003 President of Albania, Alfred Moisiu decorated him with the medal "Honor of the Nation" (Albanian: Nderi i Kombit). In 2009 a square in Dhermi was dedicated to his memory and the ceremony was attended by Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha.[7] The main theater in Vlorë bears his name.

Work[edit]

Marko's best-known works are Hasta La Vista (novel) and Nata e Ustikës (English: Ustica night) republished as Një natë e dy agime (English: One Night and Two Dawns). The latter is a 380-page novel recounting the life of prisoners at the Ustica labor camp, where Petro Marko was also imprisoned.[4] Many works of Marko exhibit surrealist motifs and patterns such as his novel Qyteti i fundit (English: The Last City), portraying the end of the Italian occupation of Albania.

In 1964 a 204-page collection of tales he wrote in his early active years from 1933 to 1937 titled Rrugë pa rrugë (English: Directionless Road) was published. Petro Marko. In 1973 his novel Një emër në katër rrugë (English: A Name at the crossroads) set in the monarchist era was published. The book was immediately banned because of its content and Marko lost his publishing rights until 1982.[1]

Sources[edit]

- ^ a b c d Elsie, Robert; Centre for Albanian Studies (2005). Albanian literature: a short history. I.B.Tauris. pp. 184–5. ISBN 1-84511-031-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Aurel Plasari (2013-11-27), Petro Marko mes zilisë dhe lavdisë [Petro Marko, between envy and glory] (in Albanian), Gazeta Panorama, archived from the original on 2013-11-30, retrieved 2013-11-28

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; John Neubauer (2004). History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. History of the Literary Cultures of East-central Europe. Vol. 2. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 93. ISBN 90-272-3453-1.

- ^ a b c Segel, Harold (2008). The Columbia literary history of Eastern Europe since 1945. Columbia University Press. pp. 17–8. ISBN 978-0-231-13306-7.

- ^ Petro Marko (2000). Interviste me vetveten, (Rete dhe guret) (in Albanian). OMSCA. ISBN 978-9992740330. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ^ Petro Marko, "Interviste me vetveten". Pjese e shkeputur nga libri i Petro Markos ["Interview with myself": extract from Petro Marko's book] (in Albanian), Libertals.com, archived from the original on 2013-12-03, retrieved 2013-11-28,

Pra c'jemi ne ? Shqiptare! Po pse e humbem gjuhen ? Une do te them ato qe di : Pse nenat plaka, gjyshet dhe gjyshet dine me mire shqipen se greqishten? Pse qajme e kendojme ne shqip ? Pse fjalet e urta i themi ne shqip ? Sic duket qe nga viti 1820 e tehu, greqizimi u be me qellim politik nga vete Greqia...[So what are we? Albanians! But why did we lost our language? I will tell what I know: Why our mothers and grandmothers know better Albanian than Greek? Why do we sing and mourn in Albanian? Why our proverbs are in Albanian? It appears that since 1820, Hellenization became a political objective from Greece itself...]

- ^ "Premier Berisha inaugurates Dhërmi village square". Albanian Government. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18.

- 1913 births

- 1991 deaths

- 20th-century Albanian writers

- Albanian people of the Spanish Civil War

- People from Himara

- Albanian communists

- Albanian-language writers

- Albanian novelists

- Albanian male writers

- Albanian resistance members

- Albanian male short story writers

- Albanian short story writers

- 20th-century short story writers