Sri Lanka–United Kingdom relations

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

| |

Sri Lanka |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| High Commission of Sri Lanka, London | British High Commission, Colombo |

| Envoy | |

| High Commissioner Amari Mandika Wijewardene | High Commissioner James Dauris |

Sri Lanka–United Kingdom relations, or British-Sri Lankan relations, are foreign relations between Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom.

Historical Overview

Pre-colonial British rule

The relationship between Sri Lanka and Western Europe goes back thousands of years, with Sri Lanka being the stop of the trades routes between the East and the West during the times of Ancient Rome and Greece.

Before Britain ruled the island of Ceylon, British sailors reached the island and the East India Company, in the 17th century, which was mainly set up to trade with South East Asia, traded more with India and Ceylon.[1] Robert Knox, a British sailor in the service of the East India Company, sailed to Persia with his father, also named Robert Knox in January 1658 on the ship, Anne. They suffered the loss of the ship's mast in a storm in November 1659, which forced them to put ashore on Ceylon. The ship was then impounded and both the Knoxes, including the ship's crew were taken captive by troops of the Kandyan king, Rajasinghe II. Robert Knox eventually escaped after 20 years of captivity to Arippu, a Dutch fort where he was treated generously by the Dutch. He was then transported to the Dutch East Indies, from where he was able to return home on an English vessel and during the voyage, Knox wrote the manuscript of An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon, about his experiences in Ceylon which was published in 1681. The book was then translated to Sinhala.

British capture of Ceylon

During the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, the British, with Sir Edward Hughes, captured Trincomalee in the eastern part of Sri Lanka in 1782.This was an assault on the Dutch-controlled port of Trincomalee which was called the Capture of Trincomalee. Though, Trincomalee was then captured by the French at the same year and was then restored to Dutch control after the Treaty of Paris in 1783. It was then in 1795-96 where Britain sent an invasion force to take control of Trincomalee and the areas of Dutch ruled Ceylon. During the Napoleonic Wars Great Britain, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796, and ending Dutch Ceylon. In 1802 the Treaty of Amiens formally ceded the Dutch part of the island to Britain and it became a Crown Colony (see British Ceylon). In 1803 the British invaded the Kingdom of Kandy in the first Kandyan War, but were repulsed. In 1815 Kandy was occupied in the second Kandyan War and a treaty called the Kandyan Convention was signed stating the terms under which the Kandyans would live as a British protectorate. This would make that Buddhism would be protected by the British Crown and Christianity would not be imposed onto the population. The treaty finally ended Sri Lankan independence after 2300 years.

The Kandyans rebelled against the British in the Uva Rebellion from 1817 to 1818. The rebellion was also known as the Third Kandyan war. The main cause of the rebellion was the failure to upload Buddhist customary traditions by British authorities as the islanders viewed it as integral part of their lives.[2] The British then won victory and the British Crown annexed Kandy into British Ceylon in 1817.

British rule

It was run as a colony affiliated to British India from 1817. During British rule on the island, the Kandyan peasantry was stripped of their lands by the Crown Lands (Encroachments) Ordinance No. 12 of 1840 (sometimes called the Crown Lands Ordinance or the Waste Lands Ordinance),[3] a modern enclosure movement and reduced to penury following the Uva Rebellion. The British found that the uplands of Sri Lanka were very suited to coffee, tea and rubber cultivation, and by the mid 19th century Ceylon tea had become a staple of the British market, bringing great wealth to a small class of European tea planters. To work the estates, the planters imported large numbers of Tamil workers as indentured labourers from south India, who soon made up 10% of the island's population. These workers were living in harsh conditions and to live in line rooms, not very different from cattle sheds.

The British colonial government favoured the semi-European Burghers, certain high-caste Sinhalese and the Tamils who were mainly concentrated to the north of the country while ignoring the other ethnic groups on the island. Nevertheless, the British also introduced democratic elements to Sri Lanka for the first time in its history. The Burghers were given some degree of self-government as early as 1833. It was not until 1909 that constitutional development began with a partly elected assembly, and not until 1920 that elected members outnumbered official appointees. Universal suffrage was introduced in 1931, over the protests of the Sinhalese, Tamil and Burgher elite who objected to the common people being allowed to vote.[3][4] Major political reforms started with the Donoughmore Commission that proposed the constitution used from 1931 to 1947. Ceylon, after the Second World War, gained independence in 1948 from the United Kingdom with DS Senanayake being the first prime minister and founding father.

Post independence

Ceylon continued to be a Dominion of the British empire which then became the Republic of Sri Lanka in 1972 and continues to be part of the British Commonwealth.

President Maithripala Sirisena made an official visit to the United Kingdom in 2015 and met Prime Minister David Cameron and The Queen,[5] while Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe made an official visit in 2018 to meet the then British Prime Minister, Theresa May.[6][7]

Timeline of Sri Lanka-United Kingdom relations

Beginning

- AD 41 - 54. During the reign of Emperor Claudius, Annius Plocamus, a Mediterranean tax collector, facilitated direct trade and first contact between Sri Lanka and the Roman Empire. During this time, the Roman Empire was invading Britain. Though, many of the Romans knew Sri Lanka as what the Greeks described it under the name of Taprobane. It was according to Gaius Plinius Secundus, as said in Natural History, it was during that time when Annius Plocamus came to Sri Lanka that the two civilisations met.[8]

- AD 54 - 640 CE. It was during that period when the Roman Empire and Sri Lanka were trading with each other and during this point of time, the years between AD 43 and AD 410, Britain (mainly England and Wales) was part of the Roman Empire. After the Fall of the Roman Empire, the contact and trade between Sri Lanka and Western Europe only happened until the arrival of the Portuguese in 1505.

- 6th century - 918 CE. The Anglo Saxon rulers of East Anglia were part of an international culture stretching from the North Sea to the Baltic Sea and beyond and traded with countries around the world. Many of the objects that were discovered at Sutton Hoo, which dated back to the Anglo Saxon times, included garnets used in jewelry pieces which may have come far away as India and Sri Lanka.[9]

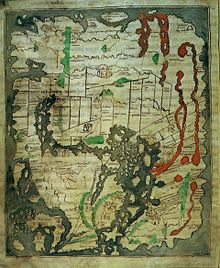

- c. 1040. The Anglo-Saxon 'Cotton' World Map was a map of the world according to the Anglo-Saxons in England. It shows the west (south) as far as the British Isles and the east (north) as far as India and Taprobanen (the Anglo-Saxon name for Sri Lanka). Sri Lanka,at that time, was known as the most distant land from the British Isles.[10]

- 1300. The Hereford Mappa Mundi, created by Richard of Haldringham, was a map depicting the world from medieval England. This map includes Sri Lanka (sometimes said to be Sumatra) as 'Taphana'.

- 1357. In the book of The Travels of John Mandeville, there had been mentions of Sri Lanka under the name of Taprobane, the old Greco-Roman name for the island. In his preface, Mandeville was a knight who was born and bred in St. Albans, England. Although the book is real, written in Anglo-Norman French, it is widely believed that "Sir John Mandeville" was not and it has been said that his travels never taken place and the book was possibly written by others such as Jan de Langhe.[11]

Early

- 1589. The first known English visitor to arrive in the island of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) was a gentleman merchant, Ralph Fitch. He arrived in Ceylon on the 6 March 1589 and stayed there for five days before arriving in London in 1591.[12]

- 1590s. English sailors and privateers crossed to the island of Ceylon. One notable was Sir James Lancaster.

- 1658. A British sea captain, Robert Knox, landed by chance in Ceylon after a storm on November 18, 1659, which suffered the ship's mast. This then forced Robert Knox and his crew to be put ashore on Ceylon. He was then captured and taken captive by the Kingdom of Kandy under Rajasinghe II. Robert Knox escaped after 19 years of captivity. He arrived back in London in 1680.

- 1667. John Milton's Paradise Lost, an epic poem published in 1667 mentions the name of Taprobane.

- 1681. A book, An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon, was published in England. The book was written by Robert Knox after his experiences on the island of Ceylon. This then gave the British to have knowledge about Ceylon.

British capture of Ceylon.

- 1782. Sir Edward Hughes captured Trincomalee from the Dutch in the eastern part of Sri Lanka during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. The assault on Dutch Trincomalee was called the Capture of Trincomalee. However, during the American Revolutionary War (1778 - 1783) Trincomalee was then captured by the French at the same year and a battle called the battle of Trincomalee was fought between the forces of France and Britain. The results were indecisive. The Treaty of Paris (1784) restored Ceylon back to Dutch control.

Battle of Trincomalee by Dominic Serres - 1795 - 96. Britain sent an invasion force to take control of Trincomalee and the areas of Dutch Ceylon. This happened during the Napoleonic Wars when Britain, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might cede Sri Lanka to the French, occupied the coastal areas of the island with little difficulty.

- 1802. The Treaty of Ameins formally ended ceded the Dutch areas of Ceylon into Britain, starting the British Ceylon period.

- 1803 - 1805. The British started to invade the Sinhalese ruled areas of the Kingdom of Kandy during the Kandyan Wars, however, they were repulsed. The first Kandyan war was caused by the intrigues of a minister of Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, Pilimatalwe, who defected the British and offered to show them the way through central Sri Lanka's winding mountain passes to the capital city. Enraged, the King of Kandy had the minister's family executed.The British dispatched two separate forces into Kandyan territory - one, under Major-General Hay MacDowall, from Colombo, and another, under a Colonel Barbut, from Trincomalee. These included 51st Regiment of Foot, the 19th Regiment of Foot, the Malay (Muslim) 1st Ceylon Regiment, the all-Sinhalese 2nd Ceylon, and the mixed Sinhalese Malay 3rd Ceylon. After fierce fighting the British force found Kandy deserted in February 1803. They swiftly established a garrison, crowned Muttusami as the new, puppet, king of Kandy, and set about subduing the remainder of the kingdom. However, the army soon suffered a number of setbacks; The Chief Minister responsible for guiding the British into Kandy had greatly inflated the extent of the king's unpopularity, and resistance proved fierce. The Kandyans resorted to fighting a guerilla war (much the same tactic as they had adopted against the Portuguese and the Dutch) and proved difficult to dislodge. Disease ravaged the garrison left behind in Kandy to secure the capital. The Kandyans counter-attacked in March and seized Kandy. Barbut was taken prisoner and executed, and the British garrison wiped out; only one man, Corporal George Barnsley of the 19th Infantry, survived to tell the tale (though other sources put the number of survivors at four).[13] In the meanwhile the retreating British army was defeated on the banks of the flooding Mahaveli river, leaving only four survivors.[14] Despite this setback the British still remained unquestioned masters of the lands they possessed, as the disastrous Kandyan counter-campaign later in the year proved. Equipped with a handful of captured six-pound cannon, the Kandyan army advanced through the mountain passes as far as the city of Hanwella.[15] Here the army was utterly routed by superior British firepower, forcing Sri Vikrama Rajasinghe to flee back into the mountains. A general rebellion that had erupted in British-controlled territory on hearing of the Kandyan invasion was suppressed. Frederick North, governor of Ceylon from 1798 to 1805, maintained pressure on the Kandyan frontier with numerous attacks, in 1804 dispatched a force under Captain Arthur Johnston towards Kandy. In a pattern that had become clear over the past two hundred or so years, the Kandyans once again defeated the British in the mountainous territory they called home. In 1805, emboldened by their successes, they captured Katuwana, a frontier town. This and the 1803 victory at the Battle of the Mahaveli, were to be Kandy's last, meaningful military successes.

- 1805-1815. Governor Thomas Maitland, in British Ceylon, initiated the legal and social reforms to strengthen the British power. These included the reform of the civil service to eliminate corruption, and the creation of a Ceylonese High Court based on the caste law. The Catholic population was enfranchised while the Dutch Reformed church lost its privileged position. Maitland also worked to undermine Buddhist authority and to attract Europeans to the colony by allowing grants of up to 4000 acres (16 km2) in Ceylon.[16] He was then replaced in 1813 by Sir Robert Brownrigg,[17] who largely continued these policies.

- February 1815. The second war between the Kandyans and British erupted. This time the British forces met scant resistance and entered Kandy on the 10th of February,in 1815 which was accompanied by John d'Oyly. Brownrigg informed the Admiralty that 'Let by the invitation of the chiefs and welcomed by the acclamations of the people, the forces of His Britannic Majesty, have entered the Kandyan territory and penetrated to the capital. Divine Providence has blessed their efforts with uniform success and complete victory. The ruler of the interior provinces has fallen into their hands and the government remains at the disposal of His Majesty's Representative'.[18] The British discovered the last king of Kandy, Sri Vrikrama Rajasinha's, hiding place; he was then exiled to Vellore Fort in India where he died 17 years later in 1842.

- March 1815. The Kandyan Convention, a treaty signed on 2 March 1815 between the British governor Sir Robert Brownrigg and the Kandyan Chiefs, marked the end of native rule for 2380 years on the island, resulted in the imprisonment of the king in India as well as resulting in the start of the British Ceylon Period. The treaty had 12 clauses in its proclamation. It was a quite unique treaty as it wasn't signed by the monarch on the throne, rather by members of the court and other dignitaries of Kandy.

Diaspora

There were about 129,076 Sri Lankan born residents in the United Kingdom according to the 2011 census.[19] Majoirty of the Sri Lankan immigrants in the United Kingdom live in London with an estimated population of 84,000 in 2011.[20]

There is also a community of European descent in Sri Lanka called the Burghers and those people are descended from the Portuguese, Dutch, English and other Europeans during the colonial era of Ceylon.

See also

References

- ^ "Trade with the East, including first contacts with India - Queen Elizabeth I and the wider world - OCR B - GCSE History Revision - OCR B". BBC.

- ^ "New Page 1". Lankalibrary.com.

- ^ "Security Verification". 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-06-22. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20090327122156/http://www.crisisstates.com/download/seminars/Spencer.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "President Sirisena meets Queen Elizabeth as UK vows to support Sri Lanka (Watch Video)". Newsfirst.lk. 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Ranil to head to London after Norway visit". Colombogazette.com. 2 October 2018.

- ^ "Crisis Meets Crisis: Ranil to Meet British Prime Minister Theresa May in London". Asianmirror.lk. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.dlib.pdn.ac.lk:8080. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Who were the Anglo-Saxons?".

- ^ https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2886&context=etd

- ^ "Visions of an Island: Real and unreal".

- ^ "Visions of an Island: Real and unreal".

- ^ "Toolserver:Homepage". Answers.com. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ "The Newsletters of the Friends of the Green Howards Regimental Museum". Archived from the original on 2006-06-15. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ [1] Archived February 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "san.beck.org". Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Robert Brownrigg: Information from". Answers.com. 2009-12-27. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ http://www.lankalibrary.com/geo/kandy4.htm

- ^ "2011 Census: Quick Statistics for England and Wales on National Identity, Passports Held and Country of Birth" (XLS). Ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Aspinall, Peter J. (2019). "The Sri Lankan community of descent in the UK: a neglected population in demographic and health research" (PDF). South Asian Diaspora. 11 (1): 51–65. ISSN 1943-8192. Retrieved 27 July 2022.