Trams in Rouen

Network map (drawn in 1994) | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Rouen |

| Locale | Rouen, Normandy, France |

| Dates of operation | 1877–1953 |

| Successor | Rouen tramway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | From 2 January 1896 |

| Length | 76 km (47 mi) (1915) |

There have been two separate generations of trams in Rouen. The first generation tramway was a tram network built in Rouen, Normandy, northern France, that started service in 1877, and finally closed in 1953. There were no trams at all in Rouen between 1953 and 1994, when the modern Rouen tramway opened.

Horse-drawn carriages and omnibuses had started at the end of the 18th century and progressively improved, but were no longer enough to provide urban services in an age of industrial and demographic growth. Local officials therefore adopted the tramway as a new mode of transport. At first they were horse-drawn, and later steam-powered; the tramway was electrified in 1896.

The network spread quickly through various city-centre districts on the right bank of the Seine, to reach the suburbs of the northern plateau, the hills of Bonsecours in the east, skirting around the textile valley of the River Cailly in the west, crossing the river and serving, in the south, the suburbs and industrial districts of the left bank.

At its largest it covered 70 kilometres (43 mi) of route, the longest network in France during the Belle Époque, and contributed to the success of events in the town's history, such as the Colonial Exhibition of 1896 and the Norman Millennium Festival of 1911.

Although the 1920s saw a slight growth in traffic, the network's expansion slowed to a halt. Private motoring had arrived to put an end to its monopoly. The rising power of buses and trolleybuses, the Great Depression in France, and above all the Second World War that ravaged Rouen and Normandy, condemned the tramway to death. The last trams stopped running in 1953, after seventy-six years of service. However, in 1994, a new Rouen tramway came to the Norman capital.

The first tramways

[edit]Horse and steam

[edit]

Rouen was integrated into the French Kingdom after Philip II of France annexed Normandy in 1204,[1] and it continued as one of the largest cities in the kingdom under the Ancien Régime. It prospered during the 19th century, with the traditional trades of textiles and Rouen manufactory (faïence) alongside the newer chemical and papermaking industries. The navigable Seine, emptying at Rouen, had been Parisians' route to the sea ever since the Middle Ages. Napoleon Bonaparte said "Rouen, Le Havre forment une même ville dont la Seine est la grand-rue" ("Rouen and Le Havre form a single town of which the Seine is the High Street"). Rouen and Orléans were the first large cities to be connected by rail to Paris, on 3 May 1843.[2] After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 – 1871, the economy of the First Industrial Revolution under the Second Empire, and the ever-growing population, obliged the Rouen city authorities to rethink the travel facilities both within the city centre and between it and the expanding suburbs.[2]

Urban services — always horse-drawn, either carriages or omnibuses on the most profitable routes — were not enough to satisfy the needs of a town that already numbered, with its suburbs, more than 170,000 people. From 1873 to 1875 the city fathers commissioned a study into building railways connecting the most populous areas of Rouen.[2] A decree was signed on 5 May 1876,[3] committing to a publicly owned standard gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in)) network, and to horse-drawn carriages. Nine lines stretching 27,500 m (90,200 ft), or 1,370 chains were decreed:[4]

| Line | From | To | Via | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pont de Pierre[Note 1] | Maromme (Half-Circle) | Le Havre sea wall Route nationale 14 |

6,600 m (330 chains) |

| 2 | Hôtel de ville | Darnétal | Place Saint-Hilaire | 3,500 m (170 chains) |

| 3 | Hôtel de ville | Sotteville-lès-Rouen (Quatre-Mares) | Pont de Pierre Soteville town hall |

4,800 m (240 chains) |

| 4 | Pont de Pierre | Le Petit-Quevilly (Roundabout) | Church of Saint-Sever | 3,300 m (160 chains) |

| 5 | Hôtel de ville | Jardin des Plantes | Pont de Pierre Church of Saint-Sever |

2,900 m (140 chains) |

| 6 | Pont de Pierre | Gare Rue Verte | Quays Rue Jeanne-d’Arc Rue Ernest-Leroy[5] |

1,700 m (85 chains) |

| 7 | Pont de Pierre | Place Saint-Hilaire | Boulevard de Nitrière Boulevard de Martainville |

1,500 m (75 chains) |

| 8 | Hôtel de Ville | Quai du Mont-Riboudet | Rue de l’Hôtel-de-Ville[Note 2] Place Cauchoise Boulevard Cauchoise[Note 3] |

1,600 m (80 chains) |

| 9 | Quai du Mont-Riboudet | Gare Rue Verte | Boulevard Cauchoise Rue de Crosne Vieux-Marché Rue Rollon Rue Jeanne-d’Arc Rue Ernest-Leroy |

1,600 m (80 chains) |

The town was authorised to tender construction and operation to one or more contractors. It quickly chose the only serious candidate, Gustav Palmer Harding, a British citizen. He was the continental representative of Merryweather & Sons, builders of steam tram engines.[6] This decision knitted the close railway links between the city and Great Britain that remained for nearly half a century. Naturally, Mr Harding wanted to promote his company's machines, so he long made his views known to the municipal authorities. Finally convinced, they authorised him to use steam power from Maromme (Line 1), entering service on 29 December 1877.[7] Merryweather & Sons, whose depot was on the Avenue du Mont-Riboudet, provided the tram units. Small and light — 4.7 tonnes (4.6 long tons; 5.2 short tons) — these reversible locomotives had two coupled axles, fully covered by a wooden body. They looked the same as a normal carriage so as not to frighten the horses. These steam carriages had enclosed lower decks; the upper decks were roofed but had open sides.[8]

The first steam trams of Léon Francq's design soon appeared on the Maromme line and coexisted with the horse-drawn tramways that served the city centre.[9]

Success and doubts

[edit]

The successful first line was soon extended to the Place Saint-Hilaire, opening on 1 June 1878. Harding then founded the Compagnie des Tramways de Rouen ("Rouen Tramways Company") (CTR)[10] and started building new sections from the Town Hall to Mont-Riboudet (Line 8; opened 3 September 1878). He also started steam traction from Darnétal (Line 2; started 23 June 1879). On the other hand, the lines that went through narrow local streets remained horse-drawn when first opened: Line 4 (opened 3 October 1878), Line 5, (opening 12 December 1878), Line 6 (opened 6 February 1879), and Line 3 (opened 27 September 1879). Line 9 was not constructed because of technical difficulties.[11]

For more than six years, twenty-three locomotives coexisted with horse-drawn trams on the Rouen network.[7] The speed and regularity of steam trams pleased passengers (the speed limit was 16 km/h (9.9 mph) between Mont-Riboudet and Maromme), but they were also expensive.[7] The frequent stops let the boilers cool down, so coal consumption was high.[12] Moreover, steam power angered both residents — who accused them of being dirty and rough-riding — and coachmen — whose animals were scared by the driver's horn and the "infernal" noise of the trains.[7] Operation thus was totally horse-drawn from 1884.[12] The CTR thus found itself in charge of a "cavalry" of around 350 horses, stabled at Trianon and Maromme, the depot at Mont-Riboudet having been disposed of.[13]

Electrification

[edit]

In 1895 the mediocrity of horse-drawn service and the prospect of the great Colonial Exposition (due to open in Rouen on 1 April 1896) made the town officials think of extension and electrification of the network.[12] Councillors were sent on study trips both in France and abroad. One councillor even spent a year in the United States.[14] At last, after much debate, the town accepted the CTR's proposals. Electrification was contracted to the company of Thomson Houston, who built the "first network", ten lines of standard gauge, either over new or re-laid tracks:[15]

| Line | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pont Corneille | Maromme |

| 2 | Avenue du Mont-Riboudet | Darnétal |

| 3 | Hôtel de ville | Sotteville railway station |

| 4 | Place Beauvoisine | Jardin des Plantes |

| 5 | Place Beauvoisine | Place des Chartreux |

| 6 | Hôtel de ville | Petit-Quevilly roundabout |

| 7 | Pont Corneille | Gare Rue Verte |

| 8 | Hôtel de ville | Rue de Lyons |

| 9 | Circular via the boulevards and quays of the right bank of the Seine | |

| 10 | Sotteville railway station | Quatre-Mares |

Longest electric tramway in France

[edit]Second network

[edit]

Infrastructure works and construction of the power station on the Rue Lemire were swiftly completed. The first electric locomotive entered service on 2 January 1896, the electrified network going live fifteen days ahead of schedule; the last horse-drawn tram saw service on 19 July on the Sotteville line.[16] After teething troubles, the new mode of transport had considerable success: in 1896 it transported over fifteen million passengers.[17] The tram sheds, holding 50 vehicles, were expanded to accommodate 25 more during the first year of service. These were classic tramcars with two axles, powered by two 25 hp (19 kW) motors (one on each axle), and had room for 40 passengers.[18] With its popular success, the network could be completed: the Line 10 extension to Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray was opened on 16 April 1899, an 11th line was constructed from Maromme to Notre-Dame-de-Bondeville (opened 17 December 1899), and a 12th from the Church of Saint-Sever to the Saint-Maur sea wall (6 February 1908).[17] The Rouen tramways had 37 km (23 mi) of lines, the largest electric network in France.[16][17] Trams were up to three cars long and ran at 20 km/h (12 mph) at 20-minute intervals.[17]

The dynamism of public transport in Rouen was an inspiration to Baron Empain who, through the intermediary of his colleague Cauderay, proposed the creation of a second complementary network.[19] He met numerous difficulties to which the CTR was no stranger, but on 17 July 1899, a new company to be called Traction Électrique E. Cauderay (a sister company of the better-known Companie Générale de Traction — CGT —) was granted the concession over five routes:[20]

| Line | From | To | Via |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gare d’Orléans | Amfreville-la-Mi-Voie | |

| 2 | Quai de la Bourse | Bapeaume | |

| 3 | Quai de Paris | Petit-Quevilly church | Pont Boieldieu |

| 4 | Quai de la Bourse | Bihorel | |

| 5 | Place du Boulingrin | Northern cemetery | Monumental |

The first services started on Line 1 on 18 January 1900, the other services starting on 10 May that year, but, facing competition from the CTR, the tramway from Petit-Quevilly was curtailed, its terminus becoming Rue Léon-Malétra.

Towards monopoly

[edit]

The second network was far less efficient than the first; In 1901 the trams transported only 1.46 million passengers over 16 km (9.9 mi) of route, being 91,000 per route kilometre (56,500 per route mile). (In 1908, over 20 million people used public transport in Rouen, 19 million with the CTR, 1.6 million with the CGT.)[21] In 1908 the CGT disposed of the second network to the Compagnie centrale de chemins de fer et de tramways because of administrative problems, a serious accident at Monumental on 6 November 1908[22] and a considerable deficit. This became an opportunity for the rival CRT, who in 1910 took over the CGT's running rights and so were finally rid of competition.[17]

The CTR was now master of all of the public transport in Rouen and its suburbs (having also absorbed the tramway and funicular railway of Bonsecours on 25 September 1909[23]). It reorganised its service to be more integrated. It also expanded the service with later-running trams, and extended Line 12 first to Champ de Courses (opened 1 January 1910) then to Bois-Guillaume (opened 4 June 1911) and Mont-Saint-Aignan (opened 15 March 1913). This last section, running over the local authority's rails, connected Grand-Quevilly (Rue de l’Église) and, on a branch, the district of Petit-Quevilly (opened 1 August 1915).[24] The network had grown to its largest, with 70 km (43 mi) of routes (including the tramway of Bonsecours).[25]

World War I

[edit]

World War I did not affect tram service in Rouen as much as it did elsewhere. After a short period of disruption during the great August 1914 mobilisation, the CTR maintained normal service during the four years of war. It overcame its reduced staffing levels with overtime, abolition of leave, and redeployment of depot personnel; nearly all conductors were promoted to motormen, to their great satisfaction. At the end of 1916, women (aged 24 or over in 1916, reduced to 23 or over in 1918) joined men on the trams, but, sexism at that time being the norm, the "wattwomen" (female motormen) were only allowed on the "easy" lines of Mont-Saint-Aignan, Bois-Guillaume and Monumental, and were not allowed on steep gradients.[24]

To satisfy military requirements, the network extended the Champ de Courses track to the Château du Madrillet, headquarters of an important BEF base. It also built a connection to transport the injured arriving by train at the Gare Saint-Sever to the main hospitals of Rouen. These installations, constructed in record time, disappeared when the war ended.[26]

Operational difficulties and closure

[edit]

Recovery and competition

[edit]During World War I the track and rolling stock received little maintenance, and by the end of the war they were in a piteous state, while expenses had increased dramatically. The problem became a crisis after the serious fire at the Trianon depot on 30 November 1921, which destroyed 70 of the 155 trams of the CTR.[24] Successive fare rises provided a stopgap, but with the new convention of 29 December 1923[27] the company announced a reorganisation of the network. A competitor had also arrived: the bus. Trams had always attracted criticism over their limited capacity, slowness and discomfort, and their encumbrance to motor cars in the city centre. Another accident on the Monumental line on 5 October 1925 hastened the inevitable: the trams lost their first route.[28]

Fightback through innovation

[edit]

Against these setbacks, the CTR still had a record year in 1928, with over 30 million journeys.[29] But from 1929, the buses took to the narrow streets in the city centre, as well as routes with low tram traffic such as Chartreux, Maromme and the circular.[29] The tramways continued as going concerns, and started large programmes of renovation and modernisation in the dozen or so years before World War II. Between 1928 and 1932, 75 first-generation trams were rebuilt to allow one man operation.[30]

The Rouen workshops presently devised two prototypes, of classical design, but with double folding doors at the front and safety devices (compressed air on one of the prototypes, electrical on the other) which became the basis for a series of 25 vehicles named "Nogentaises".[Note 4] 25 new trailing cars completed the new rolling stock. In 1931, a "revolutionary" pedal-controlled locomotive was built equipped with disc brakes, but lack of funds meant no more came of it.[31]

The 1930s also saw the arrival of the trolleybus, having the twin advantages of electrical traction and pneumatic tyres; these newcomers supplanted the old trams on the Mont-Saint-Aignan line from Sotteville and Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray. In 1938, the tram sheds were enlarged for the arrival of the "Parisiennes", ten reversible trams bought from Paris.[32]

World War II and after

[edit]

World War II hit Rouen hard, including its transport network. In 1939, before the war started, mobilisation and requisition had reduced the service frequency; the German advance, in 1940, blew up the city's bridges; on 9 June 1940 the Rouen Transporter Bridge was destroyed,[33] which split the tram network in two until 1946. With the German occupation, the lines were progressively reopened. But service was reduced. Difficulties became such during this period that the directors of the CTR[34] had to improvise mobile workshops. The heavy bombing raids of Spring 1944, in particular the destruction of the central part of the Rue Lemire, stopped the trams running.[24]

Nazi occupation ended on 30 August 1944 and Liberation slowly healed the town's wounds. It had been a catastrophe for the network: of the 76 trams in circulation in 1939, 24 had been destroyed and 25 damaged; track and overhead lines had been mutilated; the Trianon depot had been bombed several times[35] Still, service was slowly restored, thanks to the staff's hard work and above all passengers' help in shunting trailing cars. In 1945, 38 locomotives and 14 trailing cars were operational, but, despite restoration of service across the Seine on 20 April 1946, the war had struck a fatal blow.[35] Rouen was full of out-of-date equipment and so trams were progressively replaced by buses and trolleybuses.

In March 1950 the municipality decided definitely to close the tramway, but its actual closure came somewhat later. It was not until Saturday, 28 February 1953[36] that the last tram ran on the Champ de Courses line, 76 years after the network's first service. But the Rouennaise did not forget the tram's services rendered, organising a first-class funeral: Just before the last scheduled run, a parade of honour made up of three trams ran from the Hôtel de ville to the Trianon depot, cheered by the crowds.[37]

Bonsecours funicular railway and tramway

[edit]

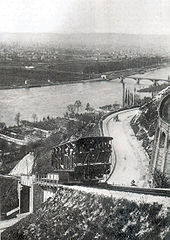

Bonsecours is a commune on a plateau to the southwest of Rouen. Until 1890 only an infrequent bus service linked it to Rouen. However, it attracted many hikers, with its splendid panoramas over the meandering Seine, and pilgrims visiting the shrine to the Virgin Mary.

Early projects

[edit]A first railway project for the mountain, later known by the name tramways de granit, was presented in 1876 by Cordier; it was one of the far-flung ideas that the railway companies often had in the 19th century. Because classical rail has poor adherence, Cordier designed a raceway made of two granite rails embedded in concrete with a continuous guide rail between them. The 2,200 m (110-chain) line, with a terminus at the Quai de la Bourse, would be served by steam carriages with a capacity of only 30 places, but capable of running on public streets as well as its special track. Because of its technical complexity the line would have been hugely expensive, the 1:1 gradient to Bonsecours requiring no fewer than 30 viaducts spanning overall 250 m (270 yd).[38] The project was soon abandoned.

Construction

[edit]In 1892 Bonsecours was finally connected to the "world below" when two Swiss engineers, Ludwig and Schopfer, built a funicular railway with water-filled counterweights. On 8 June 1892 it was formally declared open to the public and first ran eleven days later on 19 June.[39] This mountain railway, 400 m (20 chains) long and rising 132 m (433 ft), ran from the banks of the River Seine to the esplanade of the basilica. Each car could hold 90 people (50 seated), and its water tank could be filled in five minutes.[40] There were twelve journeys each way daily, more on busier days. But the ferry service from its terminus at Eauplet to Rouen was irregular, and by the end of the century it had a dangerous rival: the tramway.

At first, in 1899, the tramway was designed to be steam powered, but by 1895 this had changed to electromotive power. The line was built by the Compagnie du Tramway de Bonsecours (CTB), and first ran on 21 May 1899.[41] It was 5,600 m (280 chains) between the two termini (the Pont Corneille and the crossroads in Le Mesnil-Esnard of the RN 14 and the Belbeuf roads), with timetabling of up to 7 trams. The trams had greater power than their Rouen counterparts, with 38 hp (28 kW) motors. They could climb steep gradients (up to 9:100) and could accommodate 48 passengers, with 42 more in a trailing car.[42]

New ownership and closure

[edit]

Seventy-two daily journeys each way brought the tramway success, and it transported nearly 700,000 passengers in 1901, compared to 140,000 for the funicular, which was clearly in a dire state financially (210,000 passengers in 1898).[41] The figures were so catastrophic that on 25 November 1905 the CTB sacked the management of the railway, and liquidated the defunct Chemin Funiculaire d’intérêt local de Rouen-Eauplet au plateau de Bonsecours. Operations continued, and the CTR took over both tracks on 25 December 1909.[41] Although the tramway was always well used (900,000 tickets sold in 1913), the clientele of the funicular continued to fall (30,000 tickets collected the same year), and some daily receipts were less than 1 franc.[41] Lacking passengers, the funicular closed on 25 May 1915,[14] and the tramway became the monopoly service for Bonsecours. This date should not be confused with that for the Rouen service, which continued until February 1953.[24]

Trianon tramway

[edit]

Left bank

[edit]At the start of the 20th century the suburbs of the left bank were the quickest growing areas of Rouen, in particular the communes of Sotteville (a large railway town) and Grand-Quevilly, but these towns did not have good enough public transport. Although the CTR had constructed some lines, they did not well serve residents wishing for rapid transit between the suburbs and the city centre. Line 4 of the CTR, with its central terminus at Place Beauvoisine, ran only as far as the Trianon roundabout at the edge of the Jardin des Plantes. A southern extension was planned to the Bruyères roundabout, a meeting-point of several roads to the new districts, and to the racecourse where major horse racing events took place each Thursday. But it was always delayed.[43]

In 1903 a Sotteville man, M. Hulin, the owner and proprietor of the Château des Bruyères, grew tired of these delays and asked for the concession for a 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) narrow gauge horse-drawn tramway, which would connect the Trianon roundabout to the racecourse via the Elbeuf road, being 2,000 m (99 chains) long.[43] Two years passed in discussing the project's profitability (profit for both Hulin and M. Dagan, the engineer from the Corps of Bridges and Roads) and for tendering the construction of the line to a contractor other than the CTR. This time for reflection led to abandoning horse-drawn trams in favour of mechanical traction,[44] and moving the terminus from the racecourse entrance to the vast cemetery that the authorities intended to build,[Note 5] close to a shooting range. The CTR did not oppose the line, which would not compete with their own, so it was made a Public Local Railway[Note 6] on 10 March 1905.[45]

Small train in town

[edit]

The line was put into service on 1 April 1906, well before the official opening date of 28 April.[46] This short 2,200 m (110-chain) route, opened solely for passenger traffic, traced a rectangle between the Trianon roundabout and the racecourse, the 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) narrow gauge rails being established beside the Rue d’Elbeuf between the trees lining the road and the fences separating adjacent land (much of which was owned by Hulin).[44] Service was provided by two 24 hp (18 kW) diesel-electric locomotives, built by the Turgan workshops, each with room for 16 people,[Note 7] and the fuel depot was sited near to the racecourse. The service was particularly frequent: thirty journeys each way per day. The entire line took 10 minutes to traverse at a maximum speed of 25 km/h (16 mph).[44]

The first months' service did not meet Hulin's expectations; passenger numbers were much lower than expected, the coefficient of use[Note 8] was catastrophic: 0.39.[44] In 1906 a law was passed instituting a weekly day of rest, so it was decided, from 12 January 1907, to extend the line 800 m (40 chains) to the Madrillet roundabout at the edge of the Rouvray Forest, which was popular for Sunday walks. This 3,000 m (150-chain) double-track extension was inaugurated on 27 August 1907. The same year, diesel-electric locomotives (whose "terrible noise" frightened the horses, to the chagrin of their owners[47]) were replaced[Note 9] by electromotive traction. Two Orenstein & Koppel 0-4-0T[Note 10] steam locomotives[48] headed two open carriages each taking 16 passengers.[49] Their chimneys were fitted with spark arresters to prevent forest fires around Rouvray.

Brief life

[edit]

The line was never profitable: the coefficient of use fell to 0.32 in 1907 and passenger numbers fell to 34,000 from the 60,000 previously.[50] Except on Thursdays, horse racing day, and Sundays where the tramway took amorous walkers to the forest paths, the trams went with few passengers, often with none. What is more, the high number of return journeys reduced the possibility of making connections in Rouen: passengers on the small line may have had to wait a long time at the Trianon roundabout for a connection to the city centre.[50] The situation so preoccupied the Compagnie du Tramway de Rouen-Trianon that in January 1908 it replaced Hulin, always the driving force, and asked the Conseil Général to authorise a reduction in service frequency. But it also proposed to use four-car trams instead of two-car trams on busy days.[51] Although the departmental authorities accepted the extra cars, they would only allow the reduction of service with much red tape, as can be seen from this extract from the report of Soulier, the Conseiller général of Rouen:[52]

Il est bien entendu que, du moment qu’il ne s’agit que d’un minimum, la Société restera toujours libre de mettre en marche le nombre de trains nécessaires pour transporter les voyageurs qui se présenteront, qu’elle satisfera à cette condition, son propre intérêt est garant, et, tout en donnant satisfaction plus complète au public, son matériel sera employé judicieusement, au lieu de rouler à vide pendant une partie de la journée au détriment de son entretien. Étant donné le peu de fréquentation de cette ligne les jours de semaine, sauf le jeudi (courses), on peut parfaitement admettre la réduction à 10 des voyages pour la partie allant du champ de courses àla forêt, mais, en ce qui concerne la partie du trajet de Trianon au champ de courses, il parait indispensable à l’ingénieur en chef (Lechalas) de maintenir le minimum de voyages à 30, sinon ce serait une sorte d’abandon de la ligne, car sur cette petite distance, il ne pourra s’établir un trafic appréciable qu’à condition de présenter des départs fréquents.

— Soulier (Conseiller Génerál of Rouen), 6 May 1908

- It is well understood that, at the moment it is only a minimum, the Society is always free to put in place the number of trains necessary to transport passengers who present themselves, that if it will satisfy this requirement, its proper interest is guaranteed, and, in giving greater public satisfaction, its infrastructure will be wisely used, instead of it travelling empty for part of the day to the detriment of its business. Being given the lower frequency of service on weekdays and Saturdays, except Thursdays (racing), we can perfectly accept the reduction to ten trips to those going from the racecourse to the forest, but, concerning the part of the journey from Trianon to the racecourse, it is imperative that the Chief Engineer (Lechelas) keeps the minimum to 30, otherwise there will be a kind of abandonment of the line, because for this small distance, it will not be possible to get reasonable traffic with more frequent departures.

The service modifications lowered operating expenses, but the coefficient of use went down dramatically: 0.33 for the first ten months of 1908.[52] The decision to axe the line was made on 1 November 1908.[53] Two strategic errors had been made: wanting a service independent of the CTR's network, and putting its terminus out of town.[52] The railway was officially disbanded by a decree of 14 September 1911,[53] the rails were lifted, the public highway restored; no trace of the tramway remains.

Modern tramway

[edit]

In 1953 one of the largest electric tramways in France disappeared. But in the 1980s Rouen — and other large cities such as Nantes and Grenoble — decided that increasing traffic jams and the desire to diversify public transport needed a new mode of public transport. Discussions started in 1982 under the guidance of SIVOM (Syndicat intercommunal à vocations multiples, "Intercommune syndicate of several trades"), grouping together the communes of Greater Rouen (representing nearly 400,000 inhabitants).

In 1986, CETE (Centre d’étude technique et de l’équipement, "Technical and construction study centre") put forward a report supporting construction of a modern tramway.[54] A pre-project was launched in September 1987 and led to the Declaration of Public Utility on 22 April 1991.[55] Construction work was undertaken by GEC-Alsthom and on 17 December 1994 the first line of the modern Rouen tramway was inaugurated.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Nowadays the Pont Pierre-Corneille

- ^ Nowadays the Rue Jean Lecanuet.

- ^ Nowadays the Boulevard des Belges.

- ^ These new locomotives reused some elements of state cars on the "Nogentais Railway".

- ^ In the end, the cemetery was never built on this site, and so did not add any passenger traffic to the line.

- ^ It may be surprising that the Trianon tramway chose steam whereas the Rouen trams were electric, but the Trianon services were more rural with lower population density than the more urban Rouen ones. If this were not the guiding factor, the Trianon tramway could have all been part of the Rouen network, but this idea did not last long.

- ^ This statement is contradicted in some published articles, by Chapuis & Hulot, p. 30 and by Domengie, p. 30. The relevant information in the departmental archives relating to M. Lechalas, chief engineer, and more so those contained in the Soulier Report given to the Conseil général of Seine-Inférieure on 6 May 1908, imply that diesel-electric locomotives were definitely used before steam locomotives, see Bertin, pp. 51–52 and Marquis, p. 109.

- ^ The coefficient of use of a railway is usually calculated by dividing expenses by receipts. In many railway articles, it is given as the inverse; so that a positive result appears better than 1, which may not be clear to the reader.

- ^ There is no record of the fate of the old locomotives, perhaps they were bought for the network in Drôme which used the same kind of infrastructure; it is even possible that they were made into carriages as happened in Decauville, La Baule.

- ^ The "T" suffix signifies a tank engine: the water tank was built onto the chassis of the locomotive itself, so that a separate tender wagon was not required.

- ^ This photograph was taken at the Valence depot, but the same type ran on the Trianon line.

References

[edit]- ^ Smedley, Edward (1836). The History of France, from the final partition of the Empire of Charlemagne to the Peace of Cambray. London: Baldwin and Cradock. p. 67.

- ^ a b c Bertin, pp. 14, 184.

- ^ Marquis, p. 100.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 7–12. Details of the lines' alignments.

- ^ The Rue Jeanne-d’Arc that now leads directly to the station was not extended until the station was rebuilt in 1928. Bertin, p. 184.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Bertin, p. 186.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 36–38. Detailed description of rolling stock.

- ^ "Les premiers tramways á Paris". Musée des Transports Urbains. Retrieved 17 June 2010. ("The first tramways in Paris") (in French).

- ^ Bertin, p. 186. This became part of the Bolloré group.

- ^ Bertin, p. 186. Opening dates.

- ^ a b c Marquis, p. 105.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, p. 35.

- ^ a b Chapuis & 71, p. 17.

- ^ Bertin, pp. 186–187. Map of the network.

- ^ a b Chapuis & 71, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e Bertin, p. 187.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 52–54 Description of rolling stock.

- ^ Marquis, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 22–23. Lines' description.

- ^ Marquis, p. 106.

- ^ A runaway tram derailed at the foot of a steep slope, at the bottom of the avenue leading to Rouen's main cemetery. One person was killed and three injured. See Chapuis & 71, p. 24

- ^ Marquis, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e Bertin, p. 188

- ^ "Les Chemins de Fer Secondaires de France" [Secondary railways in France]. FACS (in French). Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Bayeux, p. 12.

- ^ Chapuis & 72, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Chapuis & Naillon, p. 22.

- ^ a b Bertin, p. 189.

- ^ Chapuis & Naillon, p. 23

- ^ Chapuis & 74, pp. 24–29. Description of rolling stock.

- ^ Chapuis & 74, p. 30.

- ^ Bertin, p. 193.

- ^ The Managing Director of the CTR, M. Triozon, was killed in the bombing of 17 August 1942. Chapuis & 72, p. 56.

- ^ a b Bertin, p. 191.

- ^ Courant, p. 123.

- ^ Bertin, p. 192.

- ^ Bertin, p. 195.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, p. 14.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b c d Bertin, p. 195.

- ^ Chapuis & 71, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Bertin, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Bertin, p. 51

- ^ Chapuis & Hulot, p. 26.

- ^ Chapuis & Hulot, p. 27.

- ^ Marquis, p. 109.

- ^ Domengie, p. 103.

- ^ Chapuis & Hulot, p. 30.

- ^ a b Bertin, p. 52

- ^ Bertin, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c Bertin, p. 53

- ^ a b Chapuis & Hulot, p. 28.

- ^ Bertin, p. 196.

- ^ Bertin, p. 197.

Sources

[edit]- Bayeux, Jean-Luc (2003). Transports en commun dans l'agglomération rouennaise [Public transport in the Greater Rouen area] (PDF) (in French). Agglomération de Rouen. ISBN 978-2-913914-66-7. ISSN 1291-8296. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-27. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Bertin, Hervé (1994). Petits trains et tramways haut-normands [Small trains and tramways of Upper Normandy] (in French). Le Mans: Cénomane/La Vie du Rail. ISBN 978-2-905596-48-2.

- Courant, René (1982). Le Temps des tramways [Railway Days] (in French). Menton: Éditions du Cabri. ISBN 978-2-903310-22-6.

- Chapuis, Jacques. "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération rouennaise ("Urban transport in the Greater Rouen area")". La Vie du Rail (in French) (71). ISSN 1141-7447.

- Chapuis, Jacques. "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération rouennaise". La Vie du Rail (in French) (72). ISSN 1141-7447.

- Chapuis, Jacques. "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération rouennaise". La Vie du Rail (in French) (73). ISSN 1141-7447.

- Chapuis, Jacques. "Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération rouennaise". La Vie du Rail (in French) (74). ISSN 1141-7447.

- Marquis, Jean-Claude (1983). Petite histoire illustrée des transports en Seine-Inférieure au s-XIXeme [Short Illustrated History of 19th Century Transport in Seine-Infériere] (in French). Rouen: Centre national de documentation pédagogique.

- Chapuis, Jacques; Hulot, René. "Le tramway du Trianon à la forêt du Rouvray" [The Forest of Rouvray Tramway]. Chemins de fer régionaux et urbains (in French) (51). ISSN 1141-7447.

- Chapuis, Jacques; Naillon, E., Les transports urbains dans l'agglomération rouennaise [Urban transport in the Greater Rouen area] (in French), vol. in the Summary of the four articles cited immediately above

- Domengie, H. (1989). Les Petits Trains de jadis : Ouest de la France [Small trains of yore: Western France] (in French). Breil-sur-Roya: Éditions du Cabri. ISBN 978-2-903310-87-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Encyclopédie générale des transports – Chemins de fer [General Transport Encyclopaedia – Railways] (in French). Vol. 12. Valignat: Éditions de l'Ormet. 1994.

External links

[edit]- The Rouen tramway on the site of the Musée des transports urbains, photos of the last trams in operation (in French)

- History of the TCAR (in French)

- Webstite of the Fédération des Amis des Chemins de fer Secondaires (in French)